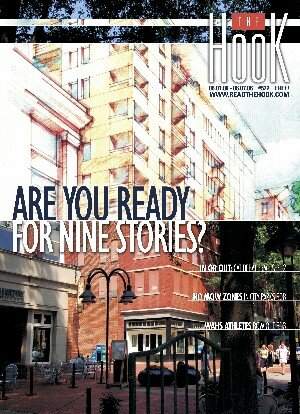

ONARCHITECTURE- No tall mall: PC okays the DZ

Almost two years after we asked the question: Are you ready for nine stories? ["#9 dreams: Invasion of the super towers," June 1, 2006], last week the Charlottesville Planning Commission answered with a resounding "no."

FILE PHOTO

Over concerns that a slew of nine-story building projects in the pipeline or already under way, which city officials fear might lead to the creation of "concrete canyons" downtown, the Charlottesville Planning Commission last week recommended a set of controversial zoning changes that will lower by-right building heights from 101 feet to 70 feet– although buildings could still be built to 101 feet with a special use permit. Addressing fears that ever-higher buildings would block the sun and "overwhelm the pedestrian scale of the area," the proposed ordinance divides the downtown area into three separate zoning districts and tweaks allowable building heights, setbacks, and street wall heights in the Mall area and along West Main Street.

In the spring of 2006, developer Keith Woodard, hoping to to take advantage of the 2003 city-wide zoning changes that sought to encourage greater density, proposed a nine-story mixed-use building for his property at First and East Main streets. Across the way, the City had already approved a nine-story project for Water Street, and was in the process of approving the nine-story Landmark Hotel project, currently under construction. In addition, there were plans in for nine-story buildings along Avon Street, in the Coal Tower area, and at the corner of Ridge-McIntire and West Main.

But it was Woodard's project that took the brunt of the City's growing nine-story building fears.

Both the Board of Architectural Review and City Council refused to let Woodard demolish the vacant properties he owns at the corner of First and Main to build his ambitious development, worrying both about the demolition of historic properties and the sheer scale of the proposed building.

Indeed, after rejecting Woodard's proposal, the City seemed almost to be on a mission to amend existing zoning.

"Now that we're seeing the reality of development starting to take place on the Downtown Mall," wrote Neighborhood Development chief Jim Tolbert to the Planning Commission earlier this year, "was that really what we wanted to see? Was that what we intended all along?"

Although the City Attorney grumbled about the "dangers" of down-zoning properties, claiming it could be seen as reducing the profitability of a building, the city persisted.

"In spite of that warning," wrote Tolbert, "it's our recommendation that we move forward with this process, and in this case the greater community good calls for these changes."

If the plan had a nickname, it might be called the Downtown Tweaking Ordinance.

Even after a year-long discussion among city planners, architects, and developers concerning the future of development downtown and along West Main, during which an elaborate variety of heights and setbacks was discussed for individual streets– in some cases, particularly along West Main, setting heights on one side of the street different from on the other– city officials and Commission members were still trying to tweak the plan. (We lost track of how many times the word "tweak" was used.)

In the final minutes of the meeting, a friendly amendment was proposed to lower from 60 feet to 50 feet the street wall height along the south side of West Main. Indeed, it might have passed had not local architect John Matthews raised his hand and pointed out that the issue had already been discussed.

"Fifty feet is an awkward height and just doesn't work with today's current construction methods," he said. "You need at least 57 feet. It would be a big mistake to drop it to 50."

Commissioner Cheri Lewis seemed to acknowledge some haphazard aspects of the ordinance– which she says she fully supports otherwise– by casting the lone "nay" vote at the end of the night. Not only did she criticize the last-minute tweaking, but she also questioned the decisions for West Main.

"I don't find a rational basis for different heights on each side of West Main Street," she says. On the South side, owners will be able to go up to 70 feet by right and 101 with a special use permit. On the North side, owners can go up to only 60 feet– 70 with a permit. Architect Gate Pratt, who lives in the West Main area, agrees.

"I'm disappointed that it was passed without addressing the differing heights on West Main Street," he says. "I think the street will look strange if developed according to the adapted height limits."

As Pratt points out, the economics of building beyond four stories may limit development on the North side, while the South side may be developed to eight or nine stories absent the same restrictions.

Further abstracting the discussion, UVA's chief architect, David Neuman, raised the issue of topography along West Main Street, pointing out that UVA's multi-story hospital is actually built 30 feet below West Main's elevation. As buildings pop up along the street, their effect on the scale of the area will depend as much on their location as on their height.

Originally the city had wanted to lower allowable density, an idea that immediately riled local developers and property owners, who felt that it would scare future developers away (reducing the potential value of their existing properties), and that it would allow only large expensive apartments downtown. But the City chose to put off that difficult discussion last week, opting instead to discuss and pass zoning amendments on height and density separately. The proposal to lower allowable density will be discussed at next month's Commission meeting.

A beleaguered Woodward was on hand last week, calling the 70-foot height limit impractical and the 50-foot setback requirement unnecessary and excessive. As he pointed out, after figuring in the cost of land and the sharp increase in construction costs for a building more than two or three stories tall, the additional two or three stories allowed would not justify the costs required.

"When you go beyond a certain height, you get into a different code area," UVA's Neuman reminded the Commission. "When you change the code– dollars. When you change the height– dollars. You have to allow some flexibility to make it economically feasible for developers."

Woodard also asked that vacant properties, like his boarded-up buildings at the corner of First and Main, be considered differently lest they remain unused, undeveloped eyesores.

Indeed, while the new ordinance might protect the downtown area from a future of looming buildings dominating the landscape, turning the Mall into a chilly, dark canyon, it might also keep Woodard's buildings boarded up, ensure the current Water Street lots remain just asphalt, and consign us to another decade of bumping over potholes in the gravel parking lot beside the Amtrak station.

#