COVER- Tornado-monium! Weather scare rocks town

.

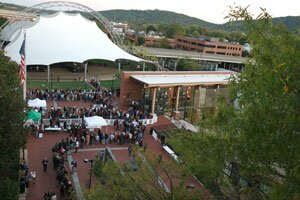

PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

Maybe it was the devastation wrought just two weeks earlier in Suffolk. Maybe it was the red-jacket-clad Storm Team newscasters who preempted the Scrubs finale to give breathless minute-by-minute tornado updates. Maybe it was the electronic message UVA sent to every student and staff member suggesting they remain indoors and "stay away from windows."

Whatever the reason, there's no doubt that panic swept some households in Charlottesville on Thursday night, May 8, after the National Weather Service issued a tornado warning for Charlottesville and Albemarle County. So was the threat real, or was everyone overreacting?

Gordon Hylton, who lives near Charlottesville High School, wondered.

"We were getting text messages from neighbors," says Hylton, who adds he was more concerned about flooding from the powerful storm than a tornado. But his four teenagers were frightened by the dire warnings– particularly, he says, by NBC29's hours-long coverage– and the family took cover on the ground level of their house armed with candles in case of a power outage.

The Hyltons weren't the only ones huddled below ground.

In the Greenbrier neighborhood, Sarah Cooper and her husband, Ryan Jacoby, had just put their children, ages 4 and 8, to bed and were watching television in their basement just after 8:30pm when they saw the tornado warning on Channel 29.

"We went up and got them and brought them down," says Cooper. When the first warning lifted– at 9:15pm– they took the kids back up to their bedrooms on the first floor, only to bring them back down when they saw a second warning soon after. Since a tornado watch remained in effect until 1am, they decided to spend the whole night in the basement in case another warning was announced.

"Once you've gone to bed, you don't know what the heck's going on," explains Jacoby.

Cooper says the recent tornado in Suffolk that destroyed homes and injured 200 people "probably had some influence" on her reaction. But she and Jacoby had another reason to be extra alert. Jacoby, director of special projects for Habitat for Humanity, manages the Southwood Trailer Park, where 150 of the estimated 1,500 residents took shelter from the tornado in the community center– the only permanent structure on the property.

It's no secret trailer parks and tornados can be a fatal mix, so following Thursday's scare, Jacoby says, he contacted the Red Cross, asking for help with "disaster preparedness." Some of the issues, he says, are how to notify residents of an incoming storm and how to transport hundreds of residents to safer locations.

Although Jacoby says he was happy to have information about the potential for a tornado, both he and Cooper contend that media coverage was "over the top."

"It was the first time I was aware of the media's impact," says Jacoby, who points out that although "we've all experienced worse storms than that," you wouldn't have known it from the coverage.

"It was five or six hours of them talking about rotation, showing scary colors on the map," he says.

Charlottesville Pavilion General Manager Kirby Hutto says he's outraged by local news coverage.

"I felt that some of the local media outlets went out of their way to sensationalize the events that took place on Thursday night," says Hutto, calling the coverage by NBC 29 "irresponsible" and pointing out that the warning covered much of the state.

"You need to be looking at what is the risk in our specific location," he says. "That's what we were looking at."

The concert featuring Sons of Bill and country rocker Gary Allen was cancelled at 9:30pm, about one hour after the first tornado warning was issued. The day after, both NBC and ABC ran stories criticizing the Pavilion for failing to call off the show earlier and potentially putting the 1,700 in attendance at risk.

Hutto stands by the venue's decisions and says the Pavilion followed its emergency protocol, which was developed with police when the venue first opened. Hutto says he and his staff were in contact with police, who he claims never told them to close.

Chief Tim Longo was out of town and did not return the Hook's call by press time; however, City spokesperson Ric Barrick says the Pavilion was advised by police to cancel the concert earlier than it did. Even so, Barrick agrees that the Pavilion stuck to its emergency plan.

"Protocol," says Barrick, "is to consider the recommendation of emergency officials but for the Pavilion to make its own decision, which it did."

In addition to communicating with police, Hutto says he and two staff members were each monitoring separate weather websites during the storm. What they saw, he says, didn't concern them. Even when the warning was issued, he says, he could see radar that suggested the signature swirling clouds– which never actually materialized into a tornado– were heading toward Fluvanna and Louisa, not toward the Downtown Mall.

Hutto says performers and concertgoers are safe even in an electrical storm because the deeply grounded massive metal arch that supports the Pavilion acts as a lightning rod. The performers had already left the stage, and the PA had been turned off. The concert was cancelled, Hutto says, when he and his staffers saw a second storm line heading toward Charlottesville, suggesting they wouldn't be able to turn on the electrical equipment anytime soon.

Neal Bennett, news director for NBC29, did not return the Hook's calls; however, the CBS and ABC affiliate, the Charlottesville Newsplex, defends its storm coverage.

"We've had a long-standing policy that whenever we go under a tornado warning we will sustain coverage until the warning is lifted," says Jeremy Settle, news director for the Newsplex. Like NBC 29, the Newsplex's ABC 16 and CBS 19 both covered the tornado warning from 8:15 until all warnings were lifted in time for the 11pm news, Settle says. A tornado warning is serious business, he explains, and warrants preemting regular programming rather than a simple crawl across the top of the screen, something Newsplex stations use for severe thunderstorms.

"Either someone has spotted a funnel cloud, or doppler radar suggests a tornado is imminent," says Settle, who insists the local stations under his control did not sensationalize.

"We pretty much presented the story as it was," says Settle, calling the coverage a "public service" and explaining that his stations lost money during the tornado coverage since they didn't even break for ads.

Marge Sidebottom, director in UVA's department of emergency preparedness, says the emergency alert– sent by text message or email to 58,000 UVA staff members and students– is a public service and is "not to inflame; it is to inform."

One climate expert defends the intense news coverage and says advance warning can save lives.

"Giving people a heads-up with 10 or 15 minutes can make a big difference," says Jerry Stenger of the State Climatology office at UVA. "It's better to issue the warning so that people can at least begin to think about what they would need to do if one looked like it was going to be coming through the front door."

Most people living on the East Coast don't have much experience with tornados– those living in the "tornado alley" states, Texas, Oklahahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, usually seem to take the brunt. But anyone living in Ivy nearly 50 years ago remembers the force and terror of a tornado.

On September 30, 1959, several twisters touched down in Ivy. The first pulled trees out of the ground and ripped roofs from homes. According to an account of the event by David Maurer, published in the Daily Progress in November 1991, the second tornado was far worse: "a howling vortex of black fury," wrote Maurer, that tore past the Ragged Mountain Reservoir before hitting two homes.

Inside the first house, the chimney was knocked down, killing one woman while sparing her husband and son. The family in the second house wasn't so lucky.

All 10 members of the Ervin Morris family were sucked up into the funnel cloud, their bodies scattered over 150 yards, according to Maurer's account, which quotes the sheriff's description of the scene: "pitiful."

A third twister touched down 30 minutes later, killing one man who'd taken cover in a cinderblock shed.

While there have been no reported tornado fatalities in Virginia this year, according to Stenger, there may be reason to fear: there have already been more tornados across the nation this year than in last year's entire tornado season– early spring to mid-summer. And the East is taking a bigger hit than it ever has before, he says, citing examples including the mid-March tornado that ripped through downtown Atlanta, and the powerful Suffolk tornado in late April.

During Thursday night's storm, one tornado did touch down in North Carolina. Scientists haven't agreed on a cause for the spike in East Coast twisters, but their preliminary suggestions range from El Niño to global warming to normal tornado variation.

Whatever the cause of the increase, Stenger, like Cooper, Jacoby, and the Hylton family, took last week's local warning seriously.

"I grabbed up my two outdoor cats and started thinking seriously about where the best place in the house would be to hunker down," he says.

He did do one thing not recommended by experts.

"I stepped outside so I could look in the direction from which the storm would likely be approaching so that I might possibly see something illuminated by lighting flashes. I was listening for the telltale sound of tornados," he adds– "a freight train." In its warning, the National Weather Service cautioned against doing that, claiming heavy rain could muffle the sound of an approaching tornado. Stenger admits that going outside to see the tornado isn't particularly wise, but jokingly defends his behavior as necessary for work.

"I am a weather professional," he laughs.

Other than to stay up watching TVs and windows, what can a sleep-deprived Charlottesvillian do to ensure a timely tornado warning?

Stenger says consumers can purchase a weather radio linked to tornado warnings from NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available for less than $50, the devices are designed to deliver loud wake-up sounds when a tornado warning is issued.

Unlike, say, hurricanes which track their path of devastation slowly across the landscape, Stenger says that a tornado really can touch down without warning. So anyone, Stenger says, who took cover in a basement– even for the entire night– shouldn't be embarrassed about overreacting.

"If I had children with me" he says, "I'd consider erring on the side of caution."

2004 UVA grads Emily and Brian Thiede learned firsthand the devastation of a powerful tornado when their Suffolk home was flattened by the twister that spared the adjacent houses on Monday, April 28.

PHOTO COURTESY KRIS BEAN

At 9:30pm on Thursday night, May 8, the Charlottesville Pavilion called off the Gary Allen concert. Some critics claimed the cancellation should have happened an hour earlier, when the tornado warning was first issued, but Kirby Hutto defends the decision. "We followed protocol," he says.

FILE PHOTO BY TOM DALY

Kirby Hutto says tornado coverage on Channel 29 was "sensationalized" and "irresponsible."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"When I realized a tornado warning had been issued and that the radar indicated the potential tornadic activity to be located southwest of me and moving toward me at 25 mph, I took that very seriously," says Jerry Stenger, research coordinator for the State Climatology Office. "That meant that, if it continued, it would probably have been on top of my house in less than five minutes."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#