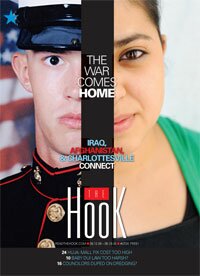

COVER- The war comes home: Iraq, Afghanistan, and Charlottesville connect

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

If war breaks out in the Middle East, and nobody's there to hear it, does it make a noise?

According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center during the week of May 26-June 1, the news stories Americans are following most closely are the presidential election, the earthquake in China, the tornados in the midwest, the collapsing housing market, the new tell-all book by former White House press secretary Scott McClellan, and the NASA Mars landing. Nowhere on the list were the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Yet for some locals, places like Fallujah and Kabul are as familiar as Crozet or Lovingston. As skirmishes erupt among the rocky cliffs and dusty streets halfway around the world, Charlottesvillians wonder if loved ones are safe and how long it will be before the sectarian violence can be peacefully resolved.

Such is the case for these five Charlottesvillians: two parents still grieving the loss of their oldest son, and three teenagers who escaped their war-torn countries and came to America to start over, but still dream of the day they can go home again.

Tuesday's children

On Tuesday September 11, 2001, the lives of these five changed forever when American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of New York's World Trade Center.

It was 8:46am in Charlottesville. At that moment, 17-year-old Brad Arms was in class at The Covenant School, where he was a senior preparing to head off to college in a year. But Arms found himself much more at home at Gold's Gym, relieving the stresses of adolescence by enduring the challenges of weight training. Here is where he decided that his was not going to be the typical college experience.

"The recruitment center for the Marines was just across the street, and he got to know some of the guys there," recalls his mother, Betty Arms. "The more he thought about it, the more he was sure he wanted the challenge of being in the military- and if he was going to be in the military, he wanted to be in the toughest branch."

Still intent on going to college, Arms agreed with his parents that he would join the Marine Reserves. Now, with the living room filled with TV images of the plumes of smoke and ash pouring out of the Twin Towers, Arms' parents were having second thoughts about the pact they had made with their son.

"Before that day, we figured, 'When was the last time the reserve had been called to active service? It would be a safe place for him to serve,'" says Betty. "Now we knew it was all fair game, and it wasn't so safe.'"

They implored their first-born to reconsider.

"We asked if he would wait a month before he signed the final papers, and he did," says Bob Arms, Brad's dad, "but there was zero pause. He knew more than ever he wanted to be a Marine."

It was 4:46pm in Moscow. Half a world away from the destruction, 11-year-old Hadiya Abdul-Satar and her 10-year-old sister, Roman, were just getting out of school.

"We turned on the TV and saw the buildings on fire, and they were talking about the numbers of people who could be dead, and I couldn't believe them," says Hadiya. "Then I watched the first tower collapse, and I knew they were right."

The sight sent the family into a panic.

"We immediately thought of my aunt who worked in New York near the World Trade Center," says Roman. "We tried calling, but the only contact we had with New York was TV."

They would eventually account for their aunt, but days later the sisters found that, for Muslims like them, the nightmare of 9/11 was just beginning.

"Everyone was terrified of Islam," says Hadiya. "Classmates called us suicide bombers. It was hard for my mother to go to work at all, let alone wear a head scarf. My father had to bribe police $1,000 a week in order to protect his shop and stay in business."

To make matters worse, not only were Hadiya and Roman Muslim, but they were also Afghani, and soon the world would know that the terrorists who planned the attack were hiding in the country they had fled as young girls. In the weeks after the attacks, it became clear that their extended family, most of whom lived in Kabul, the capital, would be in the middle of a war zone.

It was 3:46pm in Baghdad. Like people the world over, 11-year-old Fatin Hameed watched the images of collapsing rubble and fleeing New Yorkers. When word came that the terrorists who had perpetrated the acts did so in the name of Allah, the young Muslim girl became incensed at the idea that the so-called martyrs claimed to be members of her faith.

"I don't believe in jihad," Hameed says. "In Islam, you're not allowed to kill yourself or other people. These men did not go to heaven."

Some Iraqis were more ambivalent. While most world leaders offered unconditional support to the United States and grieved along with citizens of the world's great superpower, the president in Hameed's country offered this statement:

"Notwithstanding the conflicting human feelings about what happened in America yesterday," said Saddam Hussein, "America is reaping the thorns sown by its rulers in the world."

Little did Hameed know at the time, but when those American rulers heard those words, they determined to make them his last.

It was on this day that the lives of Brad, Hadiya, Roman, and Fatin began a course that ultimately united them as both Charlottesvillians and as four of the millions of people whose lives were forever changed by the United States' "war on terror."

A new kind of war

In the month between the destruction of the Twin Towers and the first American strikes against the Taliban in Afghanistan, nobody was quite sure what a "war on terror" would look like. But Hadiya and Roman Abdul-Satar knew plenty about both war and terror. When the sisters were born, the forces that had united to overthrow Soviet rule in Afghanistan were beginning to disintegrate into warring factions scrambling to fill the void left by the Russians.

By 1994, a group calling itself the Taliban– Arabic for "the students"– had begun to dominate the others, seeking to govern the mountainous, spartan country by the strictest interpretation of Muslim sharia law at the barrel of a gun. By the next year, the Taliban had gained control of Kabul, the capital city and the sisters' hometown.

It wasn't long before the little girls understood that this would have consequences for their lives.

"They had bombed a house just a mile away from us," recalls Hadiya. "They beat up our father once– enough for him to know they meant it, anyway. We knew we had to leave."

Seeking safety and to assure their daughters of an education (forbidden under Taliban rule), when Hadiya and Roman were five and four, the Abdul-Satars abandoned their home, boarded a bus with about 50 others, and made the dangerous trip 90 miles south to Jalalabad.

When men from the Taliban or the other warring factions inevitably boarded the bus every few miles, they did so to rummage through purses and wallets, and generally harass and extort. The girls were told to stay quiet. This was a rule Hadiya could not obey.

"When one of them got on the bus, I started yelling at him," she recalls. "I said, 'You burn our houses! You rob us! You kill our people!'"

For a moment, everyone on the bus feared the worst. Instead the man smiled at Hadiya and got off the bus.

"Everyone clapped," remembers Roman. "Nobody could believe my sister had done that."

For a while, the Abdul-Satars could. Four years later, when the Taliban's reign had engulfed all of Afghanistan, they made the long, clandestine, and life-threatening journey to escape from the only country any of them had ever called home.

"We were on a bus for five days, with 55 people, and the only things we had to eat or drink were bread and Kool-Aid," says Hadiya. "The only times we stopped were to use the bathroom, which we all had to do at the same time, and to bribe government officials."

The escape route ran from Jalalabad, through Pakistan, Iran, Tajikistan, and eventually to a train to Moscow, where the Abdul-Satars had some relatives to stay with. Every intersection, however, presented the threat that they could be discovered and returned to Afghanistan to face the swift, harsh judgment of the Taliban.

"I don't remember much," says Roman. "We couldn't see anything, because we had to hide from the windows."

"All I remember," adds Hadiya, "is silence."

Growing up in Baghdad, Fatin Hameed never experienced any such peril. She went to school, it was safe to walk the streets, and she never saw any of her fellow Iraqis suffer violence at the hands of her government. That's not to say a life under Saddam Hussein was fulfilling, or that Hameed saw much of a future for herself.

"Women didn't have any freedom," she says. "A woman couldn't own her own home, or live by herself. I couldn't wear shorts or a skirt in public. The government had very old ideas."

Of course, neither Hameed nor anybody else could express an opinion.

"I remember once my grandfather said something bad about Saddam," Hameed says, "and I asked my mom, 'Is [Hussein] a bad person?' And my mom looked at me very seriously and said, 'No, he's a good person. Do you understand?'"

Hameed didn't need her mother to remind her of the repercussions if she ever said otherwise.

"I knew people who had family members who disappeared suddenly," she says. "We never bothered with politics. We never touched it."

That was the situation Lance Corporal Brad Arms hoped to change when he said goodbye to his parents and boarded the bus in Lynchburg on July 5, 2004, to deploy with his fellow Marines in the Fourth Combat Engineer Battalion to Al Anbar province. His parents at once feared for his life but also stood proudly as he walked away.

"He really believed God had called him to this," says his father. "One of his buddies told me later that as they got ready to go, everyone else was all pumped up and ready to do battle, but Brad was really quiet. They asked him why, and he told them, 'Even if I don't come out alive, I know where I'm going.'"

After Hameed first spotted U.S. troops in Baghdad on April 9, 2003, it didn't take long for the 13-year-old to realize her life was going to be different in ways good and bad, as symbolized in two stark images.

"The first thing I saw were the big American tanks rolling into the streets of Baghdad, past signs that the Iraqi government had turned around to throw off the Americans, not realizing that they had GPS. Everyone celebrated, because they knew Saddam was gone," she says. "Then, not long after that, my mother was driving me somewhere and saw a dead body in the middle of the street just a few blocks from my house. I didn't see the body, but I saw her face, and I never forgot it."

It didn't take long for the war to arrive quite literally at Hameed's doorstep.

"After the invasion, my mother was always very careful, because she worked at the U.S. Embassy in the Green Zone," she says. "One day we were having a celebration at our house with family, when, out of nowhere, a mortar hit our house. Nobody was hurt, but nothing had ever scared me like that. I still don't know where it came from, and until recently, every time I heard a boom, I couldn't stay standing up."

While Hameed tried to get used to the shelling, it was a regular experience for now-Corporal Arms. But more emblematic of the war were not the dusty explosions of the improvised explosive devices, IEDs, he detonated each day, but the faces of the Iraqis he had come to the country to help.

"He would write us e-mails," says his father, "and tell us that the old men's faces had hardened into frowns, but that the children always laughed and smiled and welcomed the Americans when they would come by. He would look at those children and know why he was there."

But not long after, the war– at once seemingly so far away– arrived at the Armses' doorstep in Charlottesville in the form of two Marines in dress uniform.

"There was no question what it was," says Betty.

On November 19, 2004, while part of the Marine offensive on Fallujah, Brad Arms, in a flurry of small arms fire, had been shot in the inch-wide gap between the protective Kevlar plates strapped on his chest and back. At the age of 20, he died instantly.

Hopes for the future

Now, in Arms' hometown, Fatin Hameed, and Hadiya (both now 18) and Roman Abdul-Satar (now 17) have come as refugees, all three students at Charlottesville High School, all with the hope of attending an American university.

The three girls just finished their junior year at CHS. Among the large international population brought to Charlottesville by the International Rescue Committee's placement program, the students have been part of the fabric of CHS for some time. Still, each says that upon meeting their new American classmates in the fall, they had to dispose of lots of misunderstanding and misinformation.

"Last year, I had a class with a boy who said he wouldn't vote for a Muslim for president or any other office, because he wouldn't vote for a terrorist," says Hadiya. "I asked him, 'Do you think I'm a terrorist? Are you afraid to sit in the same classroom as me?' He was silent. We never talked again until this year, when he came to me and told me he didn't think I was a terrorist and that he was voting for Obama."

"People ask me sometimes if I'm Sunni or Shi'a," says Hameed. "I just tell them I'm Iraqi. That's what people don't realize. People in Iraq don't think of themselves as Sunni, or Shi'a, or Kurd. Only the Iranians, the Syrians, the terrorists they're sending into the country, and the corrupt government officials they're setting up. They are the ones dividing the country. Iraqis just want peace."

All three say that while they're skeptical about the troops' ability to rebuild their home countries, their family and friends on the other side of the world report shops staying open longer and streets getting safer– and they warn against a sudden pullout of the American military.

"I'm afraid for Afghanistan after the Americans leave," says Hadiya. "I'm worried there will be some other coup, and I'm afraid of the situation getting worse. I don't know if Afghanistan is ready to be independent."

"I don't know if it was a good idea for the Americans to come in the first place," says Hameed, "but I know that if the next president pulls out the troops, it's not going to get better because the Iranians, the Kurds from Turkey, the Syrians, will all come in and try to take power. It was good to get rid of Saddam, but I don't know if that would be better."

As for the place where Arms died, Al Anbar province– and the city of Fallujah in particular– is one of the infrastructure success stories military and civilian officials in Washington continue to credit to the prolonged troop presence in Iraq. As conditions improve, however gradually, both American and home country officials are encouraging former citizens residing in the U.S. to return and help with the rebuilding effort.

"Brad believed in children like these," says his father. "I hope that some day these children will go back and be leaders in their country."

"I would go back to help," says Hadiya, "but Afghanistan isn't the only poor country that needs us."

"It wouldn't be easy," says Roman. "I hope that once the country can get on its own feet, there would be an opportunity to help."

Says Hameed, "I want to be an architect, and there's plenty to be built, so why not?"

According to the Armses, it's just what their son would have wanted. In an e-mail dated 20 days before his death, he wrote: "It's the future of this country that will be different down the road; it's extremely hard to change hearts that have hated for so long. But as long as we can keep younger generations open-minded, then we will win this war, even though the fruits of my labor will not be realized for many years when the children of this country now rule."

Sisters Hadiya and Roman Abdul-Satar escaped the rule of the Taliban in the homeland of Afghanistan as young girls. They just finished their junior year at Charlottesville High School.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Fatin Hameed was born and raised in Baghdad, arriving in Charlottesville in August 27, 2007. She says the notion of a civil war in her country is actually a misnomer. "People in Iraq don't think of themselves as Sunni, or Shi'a, or Kurd," she says. "Only the Iranians, the Syrians, the terrorists they're sending into the country, and the corrupt government officials they're setting up. They are the ones dividing the country. Iraqis just want peace."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

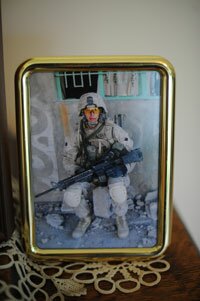

Corporal Brad Arms' job was to detect and disable the improvised explosive devices, IEDs, that have been responsible for so many of the American casualties in Iraq.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Roman and Hadiya Abdul-Satar hope to attend an American university, but say they may one day return to a free and safe Afghanistan.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Hameed wants to become an architect. She sketched throughout her interview with the Hook, and of the prospect of returning to Iraq, she says, "There's plenty to be built, so why not?"

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

On the eve of their charge into Fallujah, Corporal Arms reportedly told his fellow Marines, "Even if I don't come out alive, I know where I'm going."

COURTESY OF THE ARMS FAMILY

Bob and Betty Arms had sent their son a Christmas care package just days before his death in Fallujah. According to Betty, receiving the returned, unopened care package in November 2004, "was one of the hardest moments."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The last day the Armses got to spend with their oldest son Brad (second from left) before deploying to Iraq was July 4, 2004.

COURTESY OF THE ARMS FAMILY

#