COVER- Downtown showdown: Councilors, planners in Mall square off

In the mid-1970s, the City made the controversial decision to brick over five blocks of Main Street to create a pedestrian Mall. Now the City faces an equally controversial decision– whether to pull them all up and replace them.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Fans of the Downtown Mall have one last chance to weigh in on its planned $7.5 million renovation, scheduled to begin next January. The final public meeting on the project– announced suddenly on June 9– will be held June 30 at City Space above Bashir's on the Mall, just two weeks before City Council will decide whether to approve $4.5 million to jump-start the project.

"The drop-dead date is the second Council meeting in July," chief planner Jim Tolbert told City Councilors on June 16. "That's when Council needs to decide, or the project won't get done."

Tolbert and the MMM Design Group, the engineering firm the City has hired to plan and execute the renovation, have told Council they want to accelerate the project– starting in January and finishing by the end of spring 2009– to appease various downtown stakeholders and residents who worry the renovation could drag on for years.

"Like taking off a band-aid"– painful but quick– is the way MMM's Joe Schinstock describes the plan to pull up and replace the Mall's approximately 375,000 bricks (in addition to other upgrades and improvements) in a matter of months, a disruption that could be second only in scale to the project in the mid-1970s when City planners made the then wildly unpopular decision to create the mall.

Given the City's recent track record on Mall improvements, concerns might be well-founded.

The recent renovation and re-bricking of Third Street NE took nearly a year (about as long as it took R. E. Lee & Sons to dig up and brick over five blocks of Main Street to create the Mall in the first place)– months over schedule. Tolbert has explained that project involved replacing old utilities and burying new ones (as did the original mall project), as well as building a new concrete slab to lay the bricks on (again, as did the original project), something that won't be necessary for the main section of the Mall. Once the utilities were buried and the concrete slab was laid on Third Street, Tolbert told City Council June 16, putting the bricks down went "fairly quickly."

"The beauty of Third Street is that we've learned a lot," Tolbert said earlier this year, explaining that the problems encountered would help with staging upcoming streetscape projects.

Still, as Chris Lee of R.E. Lee & Sons acknowledges, even the most carefully planned projects can come with surprises.

by HAWES SPENCER

October 21, 1912– Commerce-heavy Main Street gets its first entertainment venue with the opening of the Jefferson Theater.

October 1959– With acres of free parking, Barracks Road Shopping Center opens and sends such a chill through Downtown merchants that they quickly organize a discount provider, Charlottesville Parking Center.

1962– Vinegar Hill, just past the western end of today's Downtown Mall– for many years the center of local African-American business and life– is razed in the name of "urban renewal."

September 1970– Charlottesville's stretch of Interstate 64 opens, so travelers and truckers no longer need Main Street.

February 7, 1974– To revitalize a dying downtown, City Council votes to turn five blocks of Main into a pedestrian mall. The next day, they break ground on the City's $2.4 million Market Street Parking Garage. Within days, the Paramount Theater, a 43-year-old Main Street movie palace, announces it will close.

January 1, 1975– Barricades are erected to block traffic, businesses brace, and excavation for underground utility vaults begins.

July 3, 1976– As the the last brick is laid at Central Place, presidential daughter Lynda Bird Johnson Robb and her husband, the pre-political-office Chuck Robb, speak at the opening.

March 5, 1980– Fashion Square Mall opens and will eventually lure such downtown anchors as Miller & Rhoads and Leggett.

August 1981– In a former drug store, actor Steve Tharp establishes Miller's, Charlottesville's most consistent jazz venue.

Thanksgiving 1982– A spectacular conflagration that destroys antiques-filled Reid's supermarket draws emergency responders from surrounding counties who manage to keep the fire from consuming the entire Mall block between east Second and Third streets.

December 1983– Because the Mall's not booming, City Council decides to build a hotel– so it doubles the hotel tax from 2 to 4 percent and creates a 3 percent meals tax.

1985– Council creates the Downtown Architectural Design Control District and its regulatory arm, the Board of Architectural Review.

May 1, 1985– At a total cost of around $20 million– including $700,000 to extend the Mall two blocks west– the City opens its own seven-story, 209-room Radisson Hotel (soon sold at a steep loss and re-branded the Omni).

Spring 1988– The first "Fridays After Five" concert happens.

Late 1980s– Eugene, Oregon; Kalamazoo, Michigan; and Fayetteville, North Carolina are among the dozens of cities digging up their failed pedestrian malls.

January 27, 1990– An unknown man stomps Michael Wayne Lively to death in a bar in the current Bizou space, and the "Fat City murder" casts a pall over revitalization efforts.

May 1990– A mysterious fire wipes out the building housing Charlottesville Appliance Company and signals the coming end of the Mall's nuts-and-bolts businesses.

December 21, 1991– The Carmike sixplex theater opens on Route 29 North. (The difficulty of finding it would inspire a recent California arrival named Lee Danielson to build a theater of his own on the Downtown Mall.)

November 1993– The 692-space Water Street Parking Garage opens, and the City reaffirms its commitment to downtown by investing $4.9 million in the $7.7-million first phase of the structure.

June 1994– City crews finish the $1.5 million eastern Mall extension which includes a grassy amphitheater and a tunnel to the 20-month-old headquarters of the Michie Company (today's Lexis-Nexis).

June 6, 1994– In his first victory in City Council, Danielson rents a few square feet of the Mall for a news kiosk he's building.

August 15, 1994– Ten days after sign-carrying protesters urging "Save the Mall," Council approves Danielson's request: a Second Street West auto crossing.

November 10, 1994– Eighteen years after its conversion to one-way status, City planners celebrate the return of Water Street to two-way traffic. Concurrently, officials cut the ribbon on improvements to Third Street SE. Mortarless concrete pavers, trees, and underground power lines cost three adjacent property owners $76,000 of the total $369,000 total.

November 30, 1995– York Place, an upscale 20-apartment/11-retailer complex, opens in the shell of the former Rose's making Chuck Lewis the Mall's top residential landlord.

April 15, 1996– City Council approves $75,000 to replace mortar between the bricks on the Mall.

May 1, 1996– Mayor David Toscano cuts the ribbon on Danielson's $4 million Charlottesville Ice Park.

August 28, 1996– A few months before the opening of the Regal Cinema, which spurred its creation, the first Mall Crossing opens.

May 1, 2006– After business urgings, City crews open another crossing on 4th Street East, but there's less controversy as it replaces a de facto crossing at nearby 7th Street East, closed in 2004.

December 15, 2004– With Tony Bennett crooning, the Paramount celebrates its gala reopening as a $14-million performing arts venue.

July 30, 2005– The Charlottesville Pavilion opens with the help of Loretta Lynn and pal Sissy Spacek.

October 2005– Former Woolworth's/Foot Locker space becomes Caspari, an upscale paper products purveyor.

March 26, 2007– The Charlottesville Transit Center opens next door to the Pavilion.

March 11, 2008– Bi-coastals Danielson and Halsey Minor break ground on a $30 million, nine-story luxury Landmark hotel.

March 26, 2008– The City installs the Mall's first recycling bins.

April 15, 2008– After multiple business incarnations, Danielson's old kiosk is hauled away for scrap.

–with reporting assistance from Coy Barefoot

One story he recalls from the original project— he was just a boy then, but the stories have been passed down in the family— was that many of the buildings along that section of Main Street didn't have basement walls facing the street. Digging crews found nothing to keep the water out when it rained. "There were irate calls from downtown property owners saying their basements had completely flooded," he says.

Lee recalls people having to walk on wooden planks over ditches to get to shops, and admits that the project may have killed some businesses. Today, the decision to brick over Main Street might seem visionary, but it wasn't until the mid-1990s, that the Mall started to become an entertainment destination— not to mention a venue for Charlottesville's most popular entertainers, the Dave Matthews Band, who played their first regular gigs there. With the building of the Regal movie theater and the Charlottesville Ice Park, the vision really began to take hold.

Naturally, some downtown stakeholders– as well as some in the local design community— are worried that the proposed renovation might destroy something that has taken so long to take root.

"I think it's a much-needed improvement," said Joan Fenton, a downtown business owner and co-chair of the Downtown Business Association, "but I'm fearful, based on the city's track record, that they will end up destroying the Mall in the process."

Indeed, that's a widely shared sentiment among those in the local design community, who fear the City is ignoring the architectural significance of the Mall's design.

Is the Mall a historic treasure?

In recent years, 92-year-old landscape designer Lawrence Halprin, perhaps now best known for his sprawling memorial to FDR in Washington, has been widely recognized as a genius for his work shaping public spaces. In 2003, he received the National Medal of Arts from President Bush, and just recently his Park Central Square in Springfield, Missouri became eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, despite being only 38 years old.

"Normally, places have to be at least 50 years old to be eligible for the register," says UVA architecture professor Elizabeth Meyer, "but because of Larry's reputation and status as a master, they're making an exception."

According to Meyer, the Charlottesville Mall is considered by many to be an even more significant Halprin design than Park Central Square.

"My fear is that this wonderful urban place designed by Halprin... will be degraded by a myriad of small-scale compromises," she told Council June 16. "The authentic landscape will be dis-assembled and carted to a landfill, and key elements of the design will be replaced with 'cosmetic upgrades.' In doing so, we will have replaced a significant modern designed landscape with a banal one."

"The Mall is more significant than most of the buildings that define its edges," added Planning Commission member Genevieve Keller, who, like Meyer, pointed out that Halprin's design meets all the criteria for a National Historic designation. "It will continue to be significant only if it is treated as a work of art, and preserved, not destroyed."

In particular, Keller and Meyer are concerned about MMM's plan to replace the existing 4" x 12" brick pavers, set in mortar, with sand-set 5" x 10" brick pavers.

A month ago, when the Hook showed Halprin the proposed Mall changes (at that time, neither MMM or City staff had thought to consult the designer, though they have contacted him since), he was most concerned about the bricks.

"I feel it's important to maintain the original brick size and pattern, as the ground level establishes the character for the Mall," he said. "If the bricks need to be replaced, I urge the City to replace them with similar ones."

Indeed, the brick size and pattern of the Mall's surface is essentially the foundation of Halprin's design, one that might be clearly recognizable, because it is so subtle, only in retrospect after it's gone. For instance, the design of the drainage runnels, which shadow the old street's curb and gutter line, is entirely dependent on the 4" x 12" brick size.

As Charlottesville resident Lydia Brandt, a PhD student in art and architectural history, told Council, "The subtleties of the design– the size of the brick, the varying levels of the street section, and the ways in which trees and furnishings are arranged to encourage a meandering pedestrian path and a series of different views– will be lost if we don't understand why these elements were included in the design."

However, those in charge of the renovation have never appeared to share the design community's– or the designer's– concerns or curiosities. Asked if he'd choose the 5" x 10" bricks over Halprin's reservations if it meant they would cost less and function better, Tolbert said yes. "It's a living, breathing space," Tolbert has said of the Mall, "not a museum."

However, as Tolbert has acknowledged, it's City Council who will have the final say on what gets built. "We'll build what Council wants," he says.

When Councilors make their final decision on July 15, the direction of the Mall renovation could very well depend on settling the issue of whether the original Halprin design, right down to the brick, is an architectural treasure worth preserving.

A Tale of Two Bricks

Ironically, shortly after City Manager Gary O'Connell announced plans for the renovation, vowing to "preserve the original design," City planners and MMM– which is earning $931,595 in consultants' fees– began arguing heavily against preserving Halprin's bricks.

In February, MMM's Schinstock told City Councilors that the existing 4" x 12" brick pavers are expensive, uncommon, and would have to be shipped from Nebraska, creating an environmentally insensitive carbon footprint.

A a Board of Architectural Review meeting in May, MMM offered new reasons to avoid the 4" x 12" bricks: they will be "unstable" if set in sand, they present a "tipping and tripping" concern, and they can't handle the "wheel load" of vehicles at the crossings.

At the same time, MMM's Chris McKnight presented a plan to use the fatter, shorter 5" x 10" bricks– which he said are more readily available, and therefore less expensive and more environmentally friendly. (They are manufactured locally by Old Virginia Brick Company, a Salem-based company that was acquired in 2006 by "a private Charlottesville-based investment group that also has holdings in banking, real estate development and building materials," according to Virginia Business.)

However, like Halprin, BAR members worried that the Mall's herringbone pattern would be radically altered by using the stubbier bricks; they asked to see sample patterns of the 5" x 10"s on larger pallets before they would approve them.

In early June, masonry expert Robert Vaughn, a member of the Virginia Masonry Association and owner of the Richmond-based masonry company Shade & Wise, said that 4"x 12" brick pavers are "very stable" if they're installed correctly and set on a firm concrete base. Indeed, the last million-dollar Mall study– a 2005 report still described by city planners as the "Master Plan"– concluded that "failing mortar joints" are the problem, not the bricks themselves.

Vaughn did say that the 4" x 12" size was "out of the ordinary," but he added that several manufacturers in Virginia or in a nearby state could probably make them. Likewise, Charlottesville masonry expert Stefani Marshall of M3 Contracting & Masonry also said that the 4" x 12" brick pavers "shouldn't be hard to obtain."

Surprisingly, Vaughn also said that he was unfamiliar with the proposed 5" x 10" sized bricks. "I've really not seen anything like that," he said. "That's a very unusual size."

Even more surprising, the 2005 study– by Philadelphia-based Wallace, Roberts & Todd with Law Engineering– pointed out that the 4" x 12" bricks could be easily obtained from General Shale Brick Company with plants in Roanoke, Marion, and Blacksburg and the Watsontown Brick Company in Pennsylvania.

On June 16– after claiming for months that the 4" x 12" bricks were available only from a manufacturer in Nebraska– Tolbert and Schinstock told Council they had "found" a manufacturer in Watsontown, Pennsylvania who could supply them– the same manufacturer listed in the Master Plan.

Still, Schinstock continued to argue against using them, saying this time that they "did not work dimensionally for a sand-set herringbone pattern" and continuing to claim that the "heavy" bricks presented a tripping hazard. In addition, Tolbert informed Council that the 4" x 12" bricks would cost "about $200,000 more" than the 5" x 10" bricks.

Councilors, however, appeared to prefer using the 4" x 12" bricks if possible. In fact, Councilor Satyendra Huja, who was instrumental in planning the original Mall project, said that he would like to see the old ones reused as a way to save money and preserve the original design, an idea that others in the design community have advanced but that Schinstock immediately dismissed, saying it wasn't feasible because 10 to 15 percent of the bricks are damaged. However, most of that damage appears to have happened in the last three years, as the WRT Master Plan in 2005 determined that less than five percent of the bricks showed "obvious signs of distress" at that time.

Raising yet another issue, M3's Marshall questions the wisdom of setting the bricks in sand. While she admits she might be biased, as the sand-set method would not require hiring masons, she says her company has often been hired to repair sand-set pavers that have been in place for five to ten years.

"Over time, the earth shifts and moves, water and dirt get under them, and there's nothing holding sand-set bricks in place," she says.

Indeed, one has too look only at the section of sand-set pavers on Third Street SE in front of the Water Street parking garage, which has already begun to shift and move along its edges after 15 years– not to mention the weeds and moss springing from cracks between the mortarless pavers.

In addition, Chris Lee points out that if the City insists on setting the bricks in sand instead of securing them with mortar, the argument over preserving their character and pattern could be moot.

"Even if you end up using the 4" x 12" bricks, if you set them in sand, they won't look the same," he says, echoing Schinstock's latest argument. "Without a mortar joint, you'll get a different appearance."

Is a Mall "renovation" even necessary?

As City planners have said, besides the bricks coming loose from their mortar joints and an electrical system in desperate need of an upgrade, the Mall is in pretty good shape– and by nearly every measure, is wildly successful.

Not surprisingly, some people wonder if an expensive renovation project is even necessary.

Downtown developer Oliver Kuttner, who built the Terraces, a 55,000 square foot mixed-use complex in the location of the old Woolworth's, has said several times in these pages that he'd rather see City staff approach the brick replacement as a maintenance issue, which he says would save millions and cause far less disruption.

"It just needs to be maintained," said Kuttner of the Mall. "There are pedestrian areas in Europe that are 200 years old. Let it become an antique old Mall. Hire a maintenance crew, some masons, and have them go up and down. It would probably cost less than $200,000 a year."

Indeed, that was WRT's recommendation in 2005. Contrary to MMM's chosen spring-time "band-aid" strategy, the WRT study recommends replacing the Mall paving over a series of years, correcting the worst areas first and doing the work during less busy times of year.

"The bricks are in such bad shape because they were not properly maintained," says Marshall, drawing attention to one of the central ironies of this very expensive project. "They're coming up now because some of those joints weren't thin enough," she says. "It's been the poor patching jobs that have caused the problems."

Indeed, that's something that Tolbert has readily admitted. "We've not done all the maintenance we could have," he said earlier this year.

A "Christmas tree" project

Interestingly, MMM's "band-aid" strategy is only one of the ways the current plan deviates from the WRT study. Just last month, McKnight's presentation to the BAR contained a host of new additions, including two new fountains (one of them a "cascading" fountain between the Omni and the ice rink), a so-called Sister City Plaza on this same west end (a series of plaques and flags to honor our six sister cities, which one BAR member called "a little bit of Rockefeller Center on the Mall"), newspaper box "corrals" to block them from view, a children's playground on the East end (which the City has asked the Charlottesville Community Design Center to study), outdoor café spaces bordered by removable bollards, spaces for public art displays, and finally— the new 5" x 10" bricks.

By mid-June, Councilors appeared frustrated with the plan they were being asked to fund, which in February they had asked to have scaled down. At that time, they made it clear that they wanted to change as little about the Mall as possible, and they didn't like the idea of adding new features, such as the two new interactive fountains.

In early June, Huja said he thought the Mall project could be done for "a lot less" and said he had asked City staff for a full budget accounting of the project to see where cost savings could be realized. Mayor Dave Norris said he was looking forward to seeing such an accounting document, adding, "[Huja]'s convinced that we can do what we need to do for half the cost the staff and consultants are proposing, and since he's clearly more of an expert on this matter than I am, I'm to a certain extent going to follow his lead on this one."

Nevertheless, at its June 16 meeting, Council was once again presented with the same complex design the BAR had seen in May. In addition, Tolbert revealed that the project could cost as much as $9.1 million after figuring in a 25 percent contingency.

"Why hasn't the price tag changed?" Norris inquired, emphasizing again that Council had asked to have it scaled back.

In response, Tolbert simply said the plan was in the "35 percent design phase" and therefore more detailed.

"I regret that it costs $7.5 million," Tolbert said later, "but I hope it doesn't cost that when we get it done."

That appeared to be of little consolation to Norris and Huja, who recited laundry lists of the proposed additions they opposed. In addition, Norris and Councilor David Brown felt the newspaper corrals, the Sister City Plaza, and the public art spaces were superfluous and unnecessary. Councilor Julian Taliaferro called for "as little change as possible." Finally, Huja likened the ongoing design process to a Christmas tree to which MMM and City staff keep gleefully adding bulbs.

"Good Lord– has the City lost its mind?" architectural historian Aaron Wunsch asked recently, echoing the sentiments of many who have followed the design process. "The prospect of radical alterations to Halprin's design is bad enough. But at such obscene cost! What does it say that even a big-time developer like Oliver Kuttner, who presumably favors public investment in such things, sees the Mall's problems as a matter of maintenance, not extreme makeover? Money seems to be burning holes in our decision-makers' pockets."

Although charged with approving funding for the project, Council chose instead to postpone that decision until July 15. However, as Tolbert and City Manager Gary O'Connell pointed out, they won't have that luxury in July, as the window of opportunity to use a $4.5 million bond issue will be closed.

Essentially, Councilors have been given an ultimatum by City staff to approve funding for a design proposal they are clearly not happy with, one that those in the design community are worried might destroy the Mall and that could cost as much as $10 million.

In the meantime, the public has grown increasingly nervous, which prompted the City to organize the up-coming last-minute public meeting. And if Mall fans feel anything like City resident David Repass, who spoke before Council decided to postpone their decision, we could be in for some fireworks.

"I'm very concerned with the process," said a visibly agitated Repass, who insisted that Council postpone its budget decision. "The public is an afterthought here. If you take action tonight, you're giving a green light to this project, and you deny the public any leverage in saying, go ahead and change your budget...please, lets try to get the public involved, especially because it is their money."

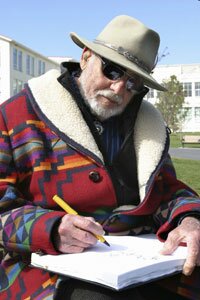

"I've always been proud of my design for the Downtown Mall," says Lawrence Halprin, 92. "It remains close to my heart." When informed about the proposed Mall renovation, Halprin expressed concern about the decision to change the size of the brick pavers. "I feel it's important to maintain the original brick size and pattern as the ground level establishes the character for the Mall," he said.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

"/images/issues/2008/0726/cover-oldbricks.jpg">"/images/issues/2008/0726/cover-oldbricksA.jpg"

"/images/issues/2008/0726/cover-oldbricks.jpg">"/images/issues/2008/0726/cover-oldbricksA.jpg"

The City wants to replace all the original 4" x 12" bricks, claiming they've detriorated beyond repair, but many of the bricks are still in good shape. "There are pedestrian areas in Europe that are 200 years old," says one Downtown developer. " Let it become an antique old Mall."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Though the thousands of pedestrians who use the thoroughfare might not know it, the distinctive herringbone pattern of the bricks beneath their feet, according to its designer, "establishes the character for the Mall."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Mayor Dave Norris would like to see the Mall's side streets– which one Downtown developer has said "look like junk"–renovated in the next five to six years. "Or, if we scale down the Mall improvements," he said recently, "then we'll have funds available to do the side streets even quicker." But City planners have said it would be too expensive.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER (NOTE: goes with side streets side bar)

First Street (south) was paved over as part of the private Terraces development, as Second Street SE will be as part of under-way Landmark Hotel project.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

In the early 1980s and early 1990s, the Mall was a veritable ghost town– one long-time Downtown business owner has said you could "fire a cannon down the Mall in the 1980s and not hit anybody." Today, it has become a successful meeting place for for frolicking adults and children alike.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

The City wants to corral café spaces on the Mall with permanent bollard inserts, as opposed to the haphazard free-standing bollards and chains there now, but the local design community fears it might "institutionalize the café spaces," something the Mall's designer, Lawrence Halprin, didn't want to happen.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Halprin's wife, Anna, a fairly well-known dancer and choreographer, has always had an influence on his designs, says Halprin scholar Beth Meyer. "'Moving through spaces' has always been key to his work," Meyer says, pointing out that the Mall's various features– the trees, the fountains, the planters, the lights– were intentionally arranged to encourage people to meander.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Kevin and Elana Woodling play with bubbles on the Mall.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Lauren Macaulay, balloon animal in hand, and Pat Stark make their way across the Fourth Street vehicle crossing.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

#