ESSAY- '130 valuable Negroes': Learning from a Monticello auction

Like Jefferson himself, his relatives didn't always keep families intact.

COURTESY MONTICELLO

This Fourth of July will find me at my job, guiding visitors through Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's mountaintop home in Charlottesville. As always, Monticello will put on a splendid show for America's birthday party, with patriotic bunting adorning its columned porticos, souvenir American flags fluttering in the summer breeze, and lively band music rousing the spirit.

And this year, as on every Fourth of July since 1963, a thousand or more visitors will gather on Monticello's manicured West Lawn, amid glorious summer blossoms– purple snapdragon and Canterbury bells, bright yellow larkspur, and scores more that Jefferson himself would have grown– to witness dozens of immigrants sworn in as naturalized American citizens.

July Fourth at Monticello is indeed a day for pomp and celebration. But for me, it's also a day for sober reflection. For as this year's honored guests are called one by one to the mansion's West Portico to be welcomed into a future bright with America's promise, I'll be reminded of a starkly different event 181 years ago at that same portico.

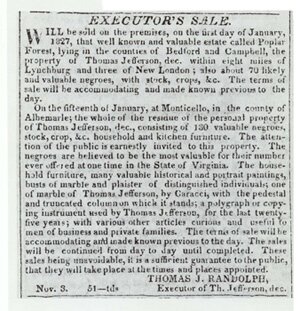

Thomas Jefferson died deeply in debt, forcing his family to sell his personal property. Thus on a frigid January day in 1827, six months after his death, crowds of people flocked to the mountaintop from near and far, drawn by the prospect of purchasing something that had belonged to America's third president and author of the Declaration of Independence.

On the auction block that day, and highlighted in large boldface on the bill of sale published in the local newspaper: 130 VALUABLE NEGROES, Thomas Jefferson's slaves.

This Fourth of July, I'll talk to my visitors about the Declaration of Independence: how Jefferson wrote it in just 17 days, for example, and feared that all 56 signers would be hanged by the British if their audacious revolution failed.

In Jefferson's bedroom, I'll recount the story of his death on the Fourth of July, 1826, and the death of America's second president, John Adams, just four hours later in Quincy, Massachusetts. People find the coincidence astonishing. Two dear friends– both Founding Fathers, both signers of the Declaration of Independence, both former presidents– dying hours apart on America's 50th birthday.

One day, after listening to the story, a young boy on my tour cleared his throat and asked, "Do you think the Declaration of Independence is, like, a curse?" I waited for the laughter of the other visitors to subside, then assured him that the Declaration is not a curse.

But he deserved a better answer from me. Because for all of the Declaration's inspirational grandeur– at last count, well more than 100 nations have declared independence since July 4, 1776– it remains, in many ways, a work in progress, a perpetual appeal to what Abraham Lincoln later called "the better angels of our nature."

This Fourth of July, from Monticello's parlor, I'll gaze upon the throng of spectators gathered on the West Lawn and the proud immigrants waiting for their names to be called to citizenship. But in my mind's eye I'll see the ghosts of those 130 men, women, and children huddled against the bitter cold of that distant January day, waiting for their names to be called, not to the promise of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," as Jefferson famously declared, but into an uncertain and foreboding future.

The Fourth of July celebrates America's birthday, but it also reminds us that there's still work to be done in perfecting our Union. And that work demands nothing less than our persistent willingness to open our arms– and our hearts– to each other.

We owe that much to the men, women, and children who answered the auctioneer's call at Monticello 181 years ago. We owe that much to the people we'll welcome there as new American citizens this Fourth of July. And we owe that much to America's Founding Fathers, who pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor in the cause of the freedoms we enjoy today.

Monticello interpreter David Ronka once won the Hook's short story contest.

#

1 comment

Once again, David Ronka's storytelling brings me to tears. His perspective is always profound and intriguing, and the juxtapostition of these two events, both of which must be claimed as a part of who we are, is quite poetic.

Sometimes I'm amazed at how much change has taken place in my lifetime, and how well we've adapted to it. Then something will happen that reminds me of just how far we still have to go.

David wrote it well: "the work to be done demands...our persistent willingness to open our arms -- and our hearts -- to each other." I would add that an added benefit is that we will be appropriately outraged when faced with injustice toward those to whom we open our hearts, and patient with one another once injustice is realized and change begins.

Love is honest, passionate and tolerant.