COVER- Single streamin', comminglin': Whatever it's called, it's tasty, less (land) filling

Steve Lawson, head of Charlottesville's public service, says since recyclables started going to Chester, the amount of recycling has increased 26 percent.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

The desire to recycle is powerful in many of us– especially when it's easy. That's why Charlottesville's quiet switch to single-stream recycling– obviating the tedious separation of glass and paper– is such a godsend to those who want to save the earth without getting their hands too dirty.

Last year, the city's recycling hauler, Allied Waste, saw an opportunity to expand its services and pick up plastics and cardboard without having to separate the materials on the street.

"We talked to the city and said we'd put it all together," says Allied's Tad Phillips. The change was possible thanks to Tidewater Fiber in Chester, a recycling sorter with facilities in Richmond, Chesapeake, and North Carolina. "We were able to piggy back on them," Phillips says.

Starting in February 2007, citizens could toss recyclables with abandon; by October, mixed paper was added to the commingled pool. Despite little notice to the public beyond City Notes, the newsletter enclosed with utility bills, the amount of recycling collected between October and March increased by 301.26 tons over the previous year, a 26 percent increase, according to Steve Lawson, the city's public services manager. During that same period, trash tonnage decreased 226.08 tons, saving Charlottesville over $14,000 in tipping fees.

Plastics and glass are losers in the recycling world because they cost more to recycle than toss. But since the advent of material recovery facilities (MRFs, pronounced "murfs") such as Tidewater Fiber– a.k.a. TFC Recycling– in Chester, and a market for paper and cardboard, centers are more willing to accept the less-desirable materials.

"The factor [MRFs] play is, if not for single stream, we wouldn't have as long a list of things we pick up," says Lawson. And he notes another advantage to mixing everything together: "The more paper you have, the less breakage."

Charlottesville paid Allied Waste $345,400 to pick up recycled materials in fiscal year 2007-08. Allied Waste gets some additional income from the sale of recyclables such as aluminum and cardboard to Tidewater Fiber, but it's not a windfall.

Lawson doesn't think the city will see any reduction in fees for the upcoming year and says collecting is Allied's main interest. "I don't think the sale of recyclables is where they're making money," he says.

Allied Waste's Tad Phillips concurs. "It costs more to process single-stream stuff," he says. While Allied saves labor costs by not having to separate materials at the curb, the cost shifts to processor Tidewater Fiber, which charges Allied to sort the materials and then gives back a rebate, based on a complex formula of what actually is in the load.

For instance, if the load is heavy on bottles, Allied is paid less. ("The fine folks in Charlottesville must have a lot of wine," observes Phillips.)

And there's the cost to truck the recycling to Chester in vehicles using 50 to 60 gallons of diesel (currently at $4.80 a gallon) per day.

The real savings, says Phillips, is not having to throw the material into a landfill– at $62 a ton. As for the myth that recycling should pay for itself, "There's always going to be a cost, unless you put gold nuggets into it," he says.

Charlottesville recycled 2,500 tons last year, and in next year's contract the city can decide to retain ownership of the recyclables and market them. "We'll be looking at a lot of things," Lawson says.

Waste Management was paid $559,356 to pick up trash last year, and that doesn't count the tipping fees, which the city paid. Its contract renewed July 1 with a four percent increase. Waste Management won't lose money if less trash goes to the landfill. "They wouldn't complain, because their price is fixed," says Lawson. "They'd love to pick up less."

In theory, citizens and businesses should be seeing a drop in their garbage sticker fees– currently $2.10 per 32-gallon or $1.05 per 13-gallon trash can.

That's certainly been the case at the Downtown Mall office of the Hook, which– with office paper as its main refuse– has been able to reduce the number of trash stickers purchased by more than half since becoming aware of the change in April.

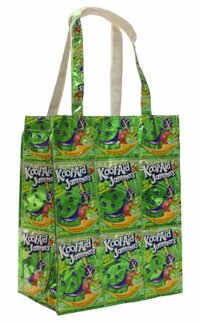

Will everyone in America soon be jamming with recycled drink pouch tote bags? TerraCycle hopes so.

PHOTO COURTESY TERRACYCLE

A national company that puts worm excrement into gallon milk jugs and sells it as fertilizer has some new ideas for hard-to-recycle items like that lunchbox standard, the drink pouch.

Each year, 4.6 billion drink pouches are manufactured and end up in landfills– until now.

"We sanitize them and sell them as pencil cases, tote bags and purses," says Albe Zakes, PR director at a Trenton, New Jersey, company called TerraCycle, founded in 2001 by two Princeton University students. The CapriSun-emblazoned products are available at Office Max and Target.

The company encourages fund-raising groups to collect empty drink pouches and pays them two to five cents for every one collected. (Honest Tea and CapriSun foot that bill.) "We hope to make our money from the sale of products," says Zakes.

That's not all. Yogurt cups hold a good-for-you product– but the container is not-so-good for the environment. TerraCycle teams up with Stonyfield Farm to pay two cents for the six-ounce cups and five cents for the 32-ounce containers. They're turned into plastic growing pots for next spring. So instead of 500 empty black plastic pots stacked in your garage, one day you'll be starting tomato seeds in yogurt containers.

But wait, there's more. TerraCycle, founded by a Princeton drop-out Tom Szaky, is recruiting nonprofit brigades to collect energy bar wrappers to make even more purses and backpacks– and cookie wrappers and granola bags to turn into umbrellas, shower curtains, and, yes, backpacks.

That hasn't been the case for nearby Rapture restaurant.

"There's been some confusion," says Rapture owner Mike Rodi. "We put out cardboard, and it gets left. I don't know if it's because we're on a commercial route and get trash pickup every day. I don't know if we have a special day. I got so much stuff from the city, maybe I overlooked it. But I've heard other merchants say the same thing."

So, in the name of keeping the streetscape clean, Rapture has reluctantly gone back to puttingtrash stickers on cardboard. "We don't want to have to bring that stuff back in," Rodi says.

"Oh, we need to talk to him," Lawson replies. "One thing that's confusing: it's two different vendors." Allied picks up recycling six days a week downtown, Lawson says, and Waste Management collects trash seven days a week. So if the red recycling bin is still sitting on the street after the garbage bags are gone, he advises giving Allied a little more time.

Other reasons cardboard might not be picked up: if it's contaminated with food or by a wax coating, as is often the case in the food industry.

Commingled recycling has rendered passé the "igloos" found at 56 multifamily dwellings all over town. "Allied is in the process of replacing them with two-cubic-yard steel containers at no extra charge," says Lawson, so drivers won't have to get out and manually empty each igloo.

In sharp contrast to the city's curbside recycling, Albemarle County's has lurched back to pre-1993, the year it started its "blue bag" program that allowed county folk to toss their bottles, cans, and plastics into one clear bag.

Albemarle ditched the program in 2003 because of its prohibitive cost, which skyrocketed from $50 a ton to have private trash haulers pick it up (something they were forced to do for free for the pleasure of doing business in Albemarle) and take the commingled materials to Coiner's Scrap Metal for sorting.

As the market for glass and plastics nose-dived around the turn of the century, the cost jumped to $150 a ton– and county conservationists discovered that their carefully sorted and washed chardonnay bottles were being dumped in a landfill.

"Our real cost to recycle was $300 a ton," says Mark Graham, Albemarle's director of community development. "The cost was mind-boggling for very little recycling, especially after finding out half the material– glass– was being thrown into the landfill."

The Board of Supervisors continues to voice support for recycling– but doesn't make any promises to expand curbside recycling beyond newspapers, which trash haulers are still required to pick up, although many citizens– and haulers– are unaware that's the case.

Faced with the county's paltry $33,000 budget for a variety of recycling projects (compared to Charlottesville's $345K commitment to curbside recycling), some Albemarleans are taking curbside recycling into their own hands.

Albemarle County Schools just announced its own commingled recycling plan in which Allied will empty dumpsters at schools and haul the contents to Chester for sorting. The school system has had a contract with Allied for years to pick up paper and cardboard.

"Allied allowed us to expand that," at no additional cost, says Lindsay Check, environmental compliance manager for Albemarle schools.

Another option for county residents is My Recycling Club. Sue Battani, owner of Cville Concierge, got the request for recycling services from some Ivy clients who said people in their neighborhood were interested in the service. If a minimum of six neighbors sign on and sort their recycling, Battani provides the bins, empties them every two weeks, and takes the material to McIntire Recycling for $20 a month per household. So far, about 50 households have signed on.

"Our main motivation is to encourage people not to give up on recycling," Battani says.

Albemarle's capital improvement budget allots $1.38 million for building recycling centers through fiscal year 2012– "exact location to be determined," according to county spokeswoman Lee Catlin. The hold-up is being blamed on concerns with the other Rivanna Authority– the Water & Sewer Authority– dealing with citizens unhappy with a 50-year water project.

"The county is waiting for Rivanna Solid Waste Authority's strategic plan," Graham says. "It was supposed to be here, but it's been delayed. All this stuff with the water supply plan has caused [Rivanna director] Tom Frederick to divert all his attention to that."

Graham adds, "There's no sense in investing a lot of money in infrastructure if the strategic plan is going to take us in a different direction."

"We're anxiously awaiting the consultants' recommendation, and know it will include some sort of curbside recycling," says Albemarle Board of Supervisors Chairman Ken Boyd. "But whether it's feasible, we don't know."

Frederick foresees a plan ready for presentation to the Rivanna board by August or September. "The question about county curbside recycling will ultimately be up to the county," he says. "We think there's a niche for us where we can find economies of scale for both Charlottesville and Albemarle."

by JEANNE SILER

1) It was only a coincidence that Mayor Dave Norris' invitation for city residents to tour the Chester recycling plant came just days before the official 2008 celebration of Earth Day. The field trip was the second city-sponsored excursion to the Chester facility to help combat skepticism about the city's recycling efforts.

2) The new, 2007 Charlottesville school bus that carried 17 interested citizens and members of the local press to the Chester plant on April 9 runs on a mixture of biodiesel fuel and gasoline. It travels at 55 mph both for greater fuel efficiency and safety reasons. School buses have a way of invoking both educational and non-educational nostalgia. They still don't have seat belts.

3) Aluminum beverage recycling is so efficient in the U.S. that within 60 days, the Diet Coke or Bud Light can you drained and pitched into a recycling bin is likely back on the grocery shelf in the form of a new can, according to Tim Lee, business development manager at the TFC Recycling Plant in Chester.

4) You can put both the glass spaghetti jar and its metallic top in Charlottesville's plastic recycling bins, but you should take the top OFF so that the powerful magnets at the recycling center that cause ferrous metals to hang upside down from conveyor belts can do their thing properly.

5) Junk mail cannot be recycled in Chester if it's shredded at home with a cross-cut shredder. All recycling at Chester leaves the cavernous tipping shed in bales, and home-shredded papers don't bale.

6) Paper products must be re-pulped and de-inked before they can be converted into new paper products– typically tissue paper or toilet paper– but yellow is the most difficult color to get out. So think about plopping phone book pages, Post-its, and yellow legal pads in the red and green bins.

7) Charlottesville– with its "pay-as-you-throw" option that allows city residents to pay for the amount of trash they put out each week– is one of only a handful of communities in Virginia with such an incentive-based fee system to promote recycling. The program is modeled after a similar program in Craven County in eastern North Carolina.

8) Charlottesville holds contracts with Allied Waste and Waste Management, the two international corporate players in the trash and recycling business. Allied Waste picks up residential recycling while Waste Management takes out the trash. Dealing with two separate companies is somewhat difficult, according to Steve Lawson, the city's public service manager, but the arrangement provides greater competition– a useful thing at July 1 contract negotiation time.

9) The global demand for cardboard packing materials allows TFC to ship bales of used cardboard to China for re-pulping and re-manufacture cheaper than selling it domestically. Because those bales may sit for six to ten weeks aboard a hot container ship, they cannot be organically soiled in the least way, the modern-day equivalent of one rotten apple spoiling the whole barrel.

10) Single-stream recycling at the TFC Recycling plant in Chester eliminates the need for city residents to sort their eligible recyclables. That ends up becoming a full-time job for some three dozen employees who work at the 60,000-square-foot tipping shed at an average wage of $8.76 an hour. "Single stream" means the mixed contents of the red and green plastic Charlottesville bins (along with the bin contents from multiple Richmond-area jurisdictions) move along a system of conveyor belts and angled screens, where the nimble employees use their hand-and-eye coordination skills to do the sorting for us.

11) One woman spent her entire eight-hour April 9 workday separating only white plastic milk containers from the conveyor belt speeding by. Wearing gloves, she sent them flying into a separate chute from beverage bottles and colored detergent-type containers where gravity helps stack them for baling. She gets two 15-minute breaks from her Lucille Ball-like routine in the morning and afternoon, in addition to a regular lunch break. [Video clip available online.]

12) The sorted recyclables from the large trailers at the Rivanna Solid Waste Authority's center on McIntire Road do not take the same route to a future incarnation that the mixed components in city curbside plastic bins do. Cans and plastics go to Coiner's, paper heads to Weyerhauser, Sonoco Recycling takes phone books, and glass travels to the Ivy Materials Utilization Center.

13) A significant number of glass bottles that originate in Charlottesville are trucked to recyclers near Harrisonburg to be crushed into small enough pieces to become part of new roadbeds in a mixture often referred to as "glasphalt."

14) Chester employees once found an entire deer carcass baled right along with four-foot bales of corrugated cardboard – "the strangest thing I've ever seen come through here," said our TFC tour guide, Andy Gupton, the processing plant manager.

15) If the Allied Waste recycling truck breaks down and an available trash truck is substituted to pick up that day's recycling along a Charlottesville route, it does not mean our recycling efforts are being trashed.

16) Once Allied Waste picks up the city's recyclables, it takes ownership of every used plastic beverage bottle and crushed beer can thrown at them. That means Allied collects the monies it earns from the sale of such throwaways, be they aluminum, glass, or cardboard. The only re-sale income the city of Charlottesville generates from its trash and recycling program is from selling the occasional large appliance– ie. white goods– to Coiners' Scrap Iron and Metal. The sale of trash stickers covers some 70 percent of the trash collection budget, according to city officials.

17) Kristel Riddervold is the City of Charlottesville's staff environmentalist.

18) A couple of years ago, the city added a third trash pickup on the Downtown Mall and West Main Street business corridors for an even higher level of service; those pickups now occur at 7am, 10am, and– soon– 4pm. Those routes generate an average of six tons a week. Commercial recycling along those same routes is available six days a week.

19) Of the city residents who set out trash cans, 35 percent use curbside recycling, a number Lawson would like to increase. By Lawson's count, residential users in the city create 8,000 tons of trash and another 2,500 tons of recyclable material each year.

20) The plastic "I Can't Believe it's Not Butter" containers are not recyclable. (And not being see-through, they're not especially useful for storing leftovers in the fridge, either.)

21) Most of the PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles– aka clear plastic beverage bottles– once they're emptied and single-streamed through the Chester recycling plant, end up under foot: they're turned into plastic flakes and sold primarily to the carpet manufacturing industry.

22) Plastic bags are among the most difficult items to contend with in the stream of recyclable materials because they get tangled in the TFC equipment, according to Gupton. Farmers in Isle of Wight County (in the southeastern corner of the state) are leading the charge among Virginians to ban the use of them because they're tired of picking them out of their cotton and peanut fields.

Consultants have suggested a local sorting center, which "might be a good role for us," Frederick says. But higher volumes are required to make it feasible, and that means both Albemarle and the University of Virginia would need to sign on.

And how significant is curbside pickup to recycling in general? "One philosophy is to make it as convenient as possible," says Frederick, noting Charlottesville's comparatively large and growing program.

He also points out the number of citizens who are committed to bringing their sorted recyclables to McIntire Recycling Center, which is run by Rivanna.

In the past year, McIntire has added cell phones, compact fluorescent lamps, and batteries to the ever-expanding list of materials it accepts.

Mercury-laden CFLs are recycled into new bulbs with partner AERL in Richmond, McIntire recycling guru Bruce Edmonds says. "They have a machine that recycles them completely," he adds. "Even the powder is recycled."

Edmonds also touts the battery program– everything except car batteries– added last month through Metal Conversion Technology from Georgia. "They're turning the batteries into a steel alloy," he says. "We've already recycled 500 pounds in the past two weeks."

McIntire has added auxiliary newspaper recycling sites at Sam's Club on U.S. 29 north, and Rose's on Pantops.

"My goal is to recycle every newspaper and catalog in the jurisdiction," vows Edmonds, who reminds that McIntire has the only phone book recycling around, which is a good thing, he says, because "We have four different phone book companies around here."

Both Edmonds and Frederick note that the community has hit a 40 percent recycle rate for the first time, up two percent from 2006 and topping the regional rate of 36 percent. That number is plumped by fall leaf collection and sewage sludge from Moore's Creek that's trucked to Richmond to be composted.

Rivanna Solid Waste Authority picked up an honorable mention from the Virginia Recycling Association, "on 100 percent recycled glass," says Edmonds. He also credits Frederick with implementing the newest recycling programs. "He's been the best friend recycling ever had at Rivanna," Edmonds says.

"You know what the most popular program over the last 14 years is?" Edmonds asks a caller. "The book bin. You wouldn't believe how much business that does." And while musty or mundane volumes (encyclopedias, Readers Digest condensed collections) are taken over to the phone book bin, others are read, a nod to the "reuse" part of the "reduce-reuse-recycle" mantra.

Downtown, some businesses are putting the emphasis on reuse. At high-end paper goods store Caspari, "We recycle our cardboard," says manager Linda Long. "We have a shredder, and we use it as a packing material."

Joan Fenton, proprietor of J. Fenton Quilts, says her store receives packages, but does little shipping. "We save styrofoam and give it away to people who ship," she says.

Eye Response Technologies has tried a different tactic to get rid of the huge amount of cardboard it gets each week. "We have so many boxes, we put them on Craigslist," says president/CEO Chris Lankford. "Within a few hours, they're gone. We don't even take them downstairs [to the street] anymore."

For paper-centric businesses like the Hook, being able to throw all recycling into one bin has saved a ton in trash stickers. But other businesses downtown seem unaware of the program.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Sue Battani saw a niche in curbside-bereft Albemarle– and had clients willing to pay $20 a month to have her company, My Recycling Club, pick up sorted glass, cans, and so on, to take to McIntire Recycling..

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

This is where your single-stream stuff goes: to the hard-working, fast-sorting folks at Tidewater Fiber in Chester.

PHOTO BY JEANNE SILER

#