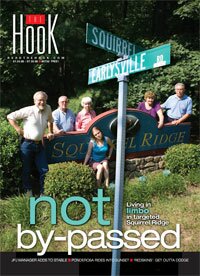

COVER- Not by-passed: Living in limbo in targeted Squirrel Ridge

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

A few months after Bill Massie moved to 312 Squirrel Path in the 1980s, he picked up the daily newspaper and was stunned by what he saw: a four-lane highway was planned to roll right through his house.

Now, 20 years later, the Western 29 Bypass still has not been built, and Massie's Squirrel Ridge neighborhood continues under a cloud. But as the Bypass seems less and less likely to materialize, the little neighborhood– that once even pleaded to be destroyed– may have the last laugh.

Located on a bluff near the Rivanna Reservoir just off Earlysville Road, the Squirrel Ridge subdivision comprises 24 houses on two curvy cul-de-sacs: Squirrel Path and Pine Cone Circle. Some of the houses perch atop hills while others rest under foliage of towering trees. Paths– for squirrels and people– run beneath the backyard canopy and around streams and ponds. On a nice day, residents work in their gardens or stroll around the hills. But every rustle of the leaves serves as a reminder of what could become of it all.

The past 20-plus years have been a time of scattered showers for Squirrel Ridge residents. And every time they think the dark clouds have cleared and the sun is out for good, the forecast again predicts a storm.

An unwelcome proposition

The proposed Bypass– beginning just south of Forest Lakes and ending near UVA's North Grounds– has been controversial since its inception in 1987 when the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved it for preliminary engineering. At a 1990 public hearing, for instance, before any houses had been purchased, 3,212 citizens opposed the bypass while just 51 approved. In 1997, when 7,100 citizens expressed their disapproval, VDOT called it the most opposition ever at a single hearing in response to a proposed transportation project.

Despite the outcry, between 1991 and 1998 VDOT began buying rights-of-way and purchased nine houses in Squirrel Ridge. But that was about as far as it went.

According to a fact sheet compiled by Albemarle Supervisor Dennis Rooker, the proposed 6.3-mile Bypass– originally estimated to cost under $90 million– is now projected to cost over $250 million.

As the plans solidified, some Squirrel Ridge residents moved away, and those who remained delayed home improvements, afraid to paint or build a deck that might end up in a wood chipper. Meanwhile, the Forest Lakes subdivision and Hollymead Town Center were built, bringing with them new traffic lights on Rt. 29 that drivers would have to navigate on their way to the Bypass.

"Most people feel it should go farther north," says Massie. "The only thing I think is gonna happen is one day they're gonna say it's dead."

His neighbor Munir Eways, a 26-year resident who served as President of the Squirrel Ridge homeowners' association, agrees. "At one time, we thought it was imminent," he says, "but now the state probably will never build it."

Squirrel Ridge was not the only neighborhood up in arms. Bob Humphris– whose late wife, Charlotte, fought the Bypass as a member of the Supervisors in the early '90s– recalls the anti-Bypass sentiment in his neighborhood, swanky Colthurst off Garth Road.

"We were completely against it," he says. "Every time I'd go out the door, I'd look up and think about how the Bypass would be right over my head."

Leading the opposition charge was a group called the Charlottesville-Albemarle Transportation Committee [CATCO], formed in 1987. In 2000, the group published Greenbook– more than 100 pages outlining the road's flaws and VDOT's alleged wrongdoings. One of the four authors, George Larie, says, "We developed the information so the public would be aware. We thought the 29 Bypass was a mistake, and VDOT was relentless in its approach."

Does VDOT consider the Bypass dead?

"When we look at a road like 29, we have to look at a long-distance as well as a local perspective," says spokesperson Lou Hatter. Mindful of the far-reaching implications of changes to a road stretching from Maryland to Florida, VDOT is currently conducting a US 29 Corridor Study to examine the impact of such changes over the next 40 or 50 years.

Senseless from an architect's eye

Ron Keeney, who took over from Eways as president of Squirrel Ridge Homeowners' Association in the early '90s and served until a year ago, describes himself as an architect and planner "by nature." And he has a laundry list of problems with the proposal.

"I kept saying, why is it so close to Hydraulic Road?" he says. "There was a place where they were going to have 11 lanes of asphalt separated by only a chain-link fence."

Also, because the neighborhood does not meet the density requirements for VDOT to erect sound barriers, all the houses would hear traffic noise. But according to CATCO's Greenbook, VDOT may have intentionally tamped down volume estimates.

Averaging the sound over a one-hour period, VDOT estimated traffic noise to be about 52.8 dBA, a seemingly tolerable rise of just three decibels. However, Parsons Brinckerhoff, a company commissioned to study the noise impact, found that noise levels of vehicles– including diesel trucks throttling up and down on the road's steep grades– would peak at 62 to 66 dB for residents living up to 2,000 feet from the four lanes. A 1995 article, "Instantaneous Change in Sleep Stage with Noise of a Passing Truck" estimates that REM sleep can be affected by noise levels greater than 60 dBA.

Take it all

By the mid-1990s, homeowners' association meetings took a turn for the surreal. After the state had purchased a third of the neighborhood and degraded the quality of life for the remaining residents, the neighbors coalesced behind an unusual– some might say drastic– idea.

"We unanimously signed a petition saying, 'You can put your bypass through the middle of Squirrel Ridge as long as you take all of us,'" Keeney says. "The bottom line was, who would want to live adjacent to a four-lane bypass through half a neighborhood?"

That solidarity earned front-page coverage in the Daily Progress on June 30, 1996. Under the headline "Inviting Obliteration," a photograph shows Keeney, arms crossed, standing in front of 25 neighbors, including a few children and seniors. The caption reads, "They'd rather see their subdivision destroyed than damaged."

But VDOT was not dismayed by the proposal. The neighborhood's death-pact plea strengthened the department's hand in its stalemate with the County over Bypass interchanges. County supervisors had required VDOT to agree that the entire 6.3-mile road would be without interchanges to keep it clear of local traffic. But state officials saw the sudden proposed addition of land as a chance to turn the entire Squirrel Ridge subdivision into an interchange with Earlysville Road. The BOS demanded that the head engineer stick to his promise. He did.

There goes the neighborhood

The prospect of having VDOT buy the entire subdivision at top dollar and give Squirrel Ridge residents a chance to start over was eventually abandoned, leaving the subdivision divided. The nine houses still stand, but they no longer shelter homeowners.

"They are tenants," says Keeney of the occupants. "They don't go out in their yard and plant trees and bushes."

Even though he served for over a decade as president of the association and appears to be a friendly guy, he still doesn't know his neighbors.

"It's dampened the enthusiasm of being a neighborhood when you don't know who's up the street," he says. "We have neighborhood barbecues in the backyard, and none of them come."

William Briggs, entering his second year-long lease of a VDOT-owned Squirrel Ridge house, says he knows his neighbors "more or less the same amount that any homeowner would."

Dark clouds shading golden years

When Cole and Roy Ann Sandridge moved into the Squirrel Ridge house they built in 1984, they were close to being the youngest couple in the neighborhood. Now in their seventies, they are among the oldest. They live in their dream home on a corner lot with a circular driveway, their living room decorated with pictures of their granddaughter. But what they didn't know when they bought the house was that they would eventually live through an experience Cole Sandridge describes as "being held captive."

When the Sandridges say "not in my backyard," they mean it literally.

At the time VDOT was buying up their neighbors' houses, it made them an offer for a tenth of an acre of their backyard with plans to create a holding pond. Cole Sandridge said the offer was too low. VDOT made another offer, but the Sandridges considered it still too low. That's when VDOT threatened to take them to court under the concept of eminent domain.

Six months later, before the court date arrived, VDOT made a higher offer, which Sandridge begrudgingly accepted.

"It's been a dark cloud hanging over our head all this time," says Roy Ann Sandridge, one of UVA's first female graduates.

"There were workshops where VDOT would show us where they planned to put in the bridges and overpasses," says her husband. "It kept us upset all the time. We were thinking of putting our house on the market, but we felt the property was devalued."

The couple say they're at an age where they'd like to move into a one-story house not located on a hill, but they fear their property value will stay low until the Bypass threat is lifted. "This is a subject that needs to be dropped," Cole Sandridge sighs.

Seller beware

Ron Keeney says that if the bypass is built, his house in the middle of the neighborhood will be located at the road's end. "I've always jokingly said to my wife that we would sit on our front porch in our old age and throw rocks at all the cars," he says.

More seriously, 12 years after they urged the state to take their neighborhood, VDOT's hesitance to take action continues to vex Squirrel Ridge residents.

"I'm still to this day living under the shadow of it," says Keeney. "It still affects my house if I go to sell it. Real estate agents estimate our houses would sell for half of what they're worth."

"These people have had their property values severely impacted for 17 years," says Rooker, a lawyer as well as a Supervisor. "Even when the market was really strong, Squirrel Ridge was hardly increasing at all. Those people have lived under the sledgehammer for years. It's a tragedy."

Realtor Roger Voisinet contends that removing the road threat would make realtors more likely to want to sell a house in the subdivision.

"A while back I had a listing for sale directly in the path of the proposed Bypass," he says, adding that he was legally required to tell anyone looking at the house what was proposed for the neighborhood. Another realtor ended up buying the property and eventually selling it to VDOT.

"Buyers take a proposed bypass into consideration even if it's a mile away," Voisinet says. He contends that the removal of the Bypass proposal would "certainly raise" values.

But what if there were a way to profit from VDOT's inaction?

A long-distance marriage

Judith Dockeray and her husband, Hugh, were planning a move in the early 1990s– Hugh had just been transferred to the Philadelphia area. But on the very first day their open house ad ran in the Daily Progress, a front-page story outlined the final route chosen for the Bypass.

"Nobody would even look at it," said Dockeray. "We felt like prisoners in our own house."

That's when she realized that the average home buyer was not her best bet. "I called the Department of Transportation every week," said Dockeray. "I was on my knees begging them to buy our house."

Around this time, Judith Dockeray recalls going out to dinner with the Sandridges. "Cole somehow knew Jack Hodge, VDOT's chief engineer, and saw him in the restaurant. I saw his face change when Cole introduced us and said my name. He looked like he wanted to high-tail it out of there." Dockeray looks back on it and laughs, "I made a terrible nuisance of myself."

But at the time, the Bypass's effect on the Dockeray family was no laughing matter. Hugh Dockeray moved to Philadelphia to start work in January of '91 leaving his wife to sell the house on Squirrel Path– a property that already looked to buyers like a ghost.

While they waited, her husband would come to Charlottesville about three weekends a month, and she would travel to Philadelphia the other weekend. "It was a very stressful time in our lives," Dockeray says. "It's just terrible to uproot families."

VDOT finally bought their house in October of '91, freeing Dockeray from what she remembers as a prison. The family returned to Charlottesville three years ago and stopped by the old house. "It looks like a disaster," Judith Dockeray says. Like Keeney, she notes that renters do not take care of the houses like the owners did.

County vs. state

Rooker seriously doubts that the project will ever be completed. "I think it stays around because of pressure from Lynchburg and Danville," he says, noting that those cities have been pushing for the Bypass for years, while the residents of Squirrel Ridge look on helplessly.

Citing research by a George Mason University economics professor that there is "no evidence that a road improvement built 20 miles away from any locality will improve their economy," Rooker contends the road has nothing to offer Charlottesville. He points out that the state's last two transportation commissioners decided the project didn't make sense from a cost-benefit standpoint.

Butch Davies, the Culpeper Representative on the Commonwealth Transportation Board, was a supporter of the Bypass during the eight years he served in the General Assembly, but, he says, after spending time analyzing the route and thinking of the cost, he realized it didn't makes sense. He cites two underlying reasons for his change of heart: growth on 29 North and limited resources.

"When the Bypass route was selected, you didn't have the intense development that has occurred," he says. "Hollymead Town Center, North Pointe, [University of Virginia] Research Park, Greene County– if you're going to do it, you ought to extend it north to Ruckersville.

"Two years ago, VDOT estimated that the project would cost $160 million," he adds. "Now it's up to a quarter of a billion dollars for a 6-mile road– and how can you justify that?"

Davies notes that the $270-million, 13-mile Lynchburg Bypass stretches far into the countryside, unlike the local western Bypass, which would run right through pricey neighborhoods near the heart of Charlottesville.

Only 9-11 percent of traffic in Charlottesville is through traffic, according to Juandiego Wade, Albemarle County Transportation Planner. The remainder are local drivers who might not make use of the Bypass on a daily basis.

The Bypass has been selected four times by Friends of the Earth and by Taxpayers for Common Sense as one of the worst transportation projects in the country. Additionally, the Charlottesville-Albemarle Metropolitan Planning Organization has voted against federal construction funding every year since 1996.

George Gercke, who moved into his Squirrel Ridge home in 1981, attributes his neighborhood's nearly 20-year struggle to the division of power between the state and localities: "This is awkward for modern society," he says, adding that this division makes projects like the Bypass that require massive funding, "take lifetimes to work through."

$75 a trip?!

Kent Shelton, City Engineer for Lynchburg and Danville, says the proposed Bypass would improve Lynchburg's economy. "As far as shipping goods to Northern Virginia goes, it would reduce the cost for companies," he says. Shelton cites Madison Heights, completed in 2005, as an example of an effective Bypass whose example the Charlottesville road could follow.

A bypass around Charlottesville's 29 corridor is Lynchburg and Danville's number-one priority. According to Rex Hammond, President and CEO of the Lynchburg Chamber of Commerce, Route 29 is Lynchburg's interstate– its main thoroughfare. He says that of the three major north-south roads in Virginia– Route 29, along with Interstates 81 and 95– is the most direct route through Central Virginia. Hammond contends that truck drivers lose crucial time on 29's Charlottesville bottleneck.

"US 29 is not a local road; it's not Charlottesville's main street," Hammond says. "It's a highway of US significance. If 29 is obstructed, people are encouraged to take other routes. If you choke off a grapevine, it will kill the fruit."

Rick Thompson, owner of Thompson Trucking in Lynchburg, is one of the ones allegedly choked– to the tune of $75 per trip through Charlottesville.

He says the 29 business corridor takes 30 to 60 minutes to get through, and using his calculations of gas prices and hourly wages, his company loses $75 every time a truck drives through Charlottesville.

(Thompson says that before the Madison Heights district of Lynchburg was bypassed, his drivers spent about 45 minutes to an hour to get through. Now, with a bypass completed in 2005, they take only 12 minutes.)

According to Hammond, the possibility of overpasses and an expressway– two other proposals for navigating around Charlottesville– won't work. "The notion of taking this volume and sending it through the heart of the city is an erroneous and expensive proposition," he says.

Hammond stresses the importance of a 29 Bypass for everyone. "It's not us against them. This is about building the best transportation possible that can be ours, yours, and the eastern part of the country's."

The fine print

While these projects may take lifetimes to debate, the 29 Bypass debate may be ending soon. According to Virginia Code Section 33.1-90, which deals with the acquisition of property for transportation projects, VDOT must begin construction within 20 years of purchasing any property.

If construction does not begin within that time frame, the former owner of the property has 90 days to request the parcel back– in writing– for the price VDOT paid. It's as if 20 years of appreciation never happened.

At Squirrel Ridge, houses were purchased "for top dollar at the time in order to quell opposition," according to Massie. "Top dollar" translated to $168,000-$217,000 for each of the five houses purchased in the early '90s, and $220,000-$295,000 for the houses purchased in 1998.

These homeowners, who undoubtedly felt unlucky in the '90s, may see karma come back around. In 2011, a previous owner of 353 Squirrel Ridge, a 1,975-square-foot house built in 1985 on over an acre of land, with 3 bedrooms and 2.5 baths, will be able to buy it back from VDOT at the stunning price of $173,000.

Realtor Voisinet estimates that the value of Squirrel Ridge properties, free of Bypass threats, would range from around $350,000 to $400,000.

Also in 2011, Joe Graham, the former owner of a house built in 1990, who was forced to surrender his one-year-old property to the state, will be able to buy it back for $216,000. This house, also on over an acre of land, features 4 bedrooms and 2.5 baths in 2,387 square feet.

Graham bought the property as a spec house, an action he describes now as "naive." While he says he's heard of the 20-year rule, he's unsure of the specifics, but he's delighted that the 90-day period might not lie too far in the future.

"I certainly would be most interested in reacquiring that house," says Graham. "Who wouldn't be?"

According to Supervisor Rooker, the state is required to offer the house to the original owner first. If that owner does not act within 90 days, "VDOT will want to sell it to someone else," he says. "They have an asset not increasing in value and projects that need to be funded. The sooner money is obtained from the right of way, the better off everyone will be."

But the Virginia Code section has a few provisions that make it a bit tricky: the 20-year period can be extended when it's applied to a proposal on the CTB's six-year improvement plan or a county board's six-year improvement program for secondary roads, so long as steps have been taken to move forward.

Rooker believes this could be interpreted either way in the 29 Bypass situation: while no construction steps have been taken to "move forward," preliminary engineering steps have been. Further complicating things is a provision stating that "any delay occasioned by litigation" is not counted in the 20 years. The 29 Bypass project was once delayed by a suit against VDOT requiring it to conduct an environmental study.

"The Code is to open interpretation until the courts get a case," says Rooker. To his knowledge, there has not yet been a precedent case related to the improvement plan stipulations in this section.

A dead animal

"I think it's a dead animal at the moment," says Keeney. "It's been stopped, and someone would have to figure out how to restart it." And like trying to revive a dead animal, the process would likely be messy and futile.

Gercke contends that the bypass was proposed in a different era, a time where the only development north of the road consisted of a graveyard and a couple of small shops. He notes that the bypass idea "hasn't officially been killed, but it makes so little sense that we feel somewhat safe that it isn't gonna happen."

Keeney agrees that the 29 Bypass's time of making sense has come and gone. "To build that Bypass now would be like coming into the middle of the town and turning right," he says. "It should have been outside of the airport."

Not making the grade

VDOT ranks roads by letter, with an "A" rating indicating that cars travel at an average speed of 30 mph or more. According to a fact sheet provided by the Board of Supervisors, VDOT's traffic studies confirm that the level of service in the Route 29 corridor of Albemarle County is currently "F," and even with the proposed bypass it would still receive an "F." A score of F indicates that up and down this particular corridor, the average traveling speed is less than ten miles an hour.

Less expensive improvement options exist– a plan to turn the stoplights at Hydraulic, Greenbrier, and Rio into grade-separated interchanges, for example– that could score the Route 29 corridor an "A" level of service. Another viable, less expensive option– putting "expressway lanes" on 29– could bring the arterial 29 corridor up to a "C" level of service.

CATCO's Greenbook includes a 1990 VDOT study that shows estimated travel times for each traffic alternative. The current travel time on the business corridor of Route 29 is 25.1 minutes. While the bypass would shorten travel time to 14.0 minutes, simply creating the three interchanges would decrease travel time on Route 29 to 15.1 minutes. This alternative coupled with the expressway lanes would cut travel time on the expressway to only 13.7 minutes. Neither the expressway nor the interchanges would require the destruction of any houses.

Still part of the plan

As safe as Squirrel Ridge residents are from the threat of the bypass happening, they are still miles away from it officially not happening. According to VDOT's Hatter, the project remains on the department's six-year improvement plan although there is no projected completion date.

Roy Ann Sandridge sighs. "If they're not ever going to do it, I wish they'd say so," she says. "I think they owe us that."

There are decades of anger in Cole Sandridge's voice. "Tell us it's not gonna be done or tell us it's gonna be done– and do it!" he exclaims.