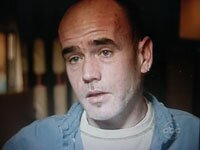

Painful puzzle: Abshire talks about the fatal night

ABC NEWS

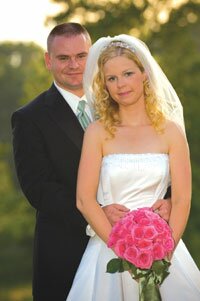

It was first considered a tragic but straight-forward incident of hit and run on a winding, moonlit country road in Barboursville. But the 2006 death of Justine Swartz Abshire, a 27-year-old kindergarten teacher, continues to vex investigators, as a series of discrepancies surround the late woman's husband, who insists on his innocence.

Last month, the tragedy found a national audience when ABC Primetime Crime, capping a year-long investigation by the network, aired an hour-long episode on Justine's death that revealed some startling new clues. But despite the new information– including phone records and a battery of injuries inconsistent with the original story– questions remain: How did Justine spend her final hours? Why did it take her husband as long as 18 minutes to call 911 after he discovered his wife's body? And how did Justine really die?

The biggest question of all, however, is one that has been whispered throughout the community for nearly two years: Did Eric Abshire murder his wife? Or is he– as he claims– a grieving widower scapegoated by devastated parents and a frustrated police force with no other suspects?

Last week, for the first time, Abshire agreed to sit down with the Hook for an interview about the circumstances surrounding his wife's death and his frustration with the case he believes may remain forever unsolved.

Hopes dashed

At a local coffee shop on a recent weekday afternoon, Abshire relates that in the weeks following Justine's death on the morning of November 3, 2006, he was sure someone would offer police the name of the person who might have run down his wife.

"I kept expecting one person to call," says Abshire. "It's hard enough for one person to keep a secret, much less two or more."

All it might have taken is for someone to have returned home with a damaged vehicle or told even one friend that he'd struck a pedestrian, so Abshire says he believed that eventually the full truth would come out. Nearly two years later, it hasn't.

There were plenty of reasons to believe the case would be quickly solved. After all, Taylorsville Road, where Justine was found, is a local route– narrow, winding, less than two miles long. Stretching from Toms Road on the west end (where it starts as Heights Hill Road) to Albano Road on the east and parallel to busy Route 33, it's not easy to stumble upon.

Like many rural roads, Taylorsville Road is considered a comfort zone only for those who live there or who know the local shortcuts; and it's particularly quiet during the wee hours, say several residents along the stretch where Justine was found.

The silence that morning was broken minutes before 2am– but not by the screech of skidding tires or a woman's scream. Neighbors interviewed by the Hook say the first noise was a loud knocking, first at the door of Marvin Ruffner's house at 2501 Taylorsville Road.

By the time Ruffner awakened and looked outside, he could see a man standing on the front porch of his neighbor's house across the street. And there was something else.

"I could see," says Ruffner, "this woman laying there in the road."

Across the street, the banging at the door of 2572 Taylorsville Road, a trailer with a small front porch and a lighted outdoor lamp, awakened then 18-year-old Amber Lamb who was sleeping on a sofa in a living room.

"It sounded like someone was kicking the door in," says Lamb, reached by phone last week. Lamb, now 20, says she heard a man's voice saying, "Help, help! I need help!"

Although she was frightened, she says her grandmother told her to open the door and see who was there. It was Abshire.

"He said, 'I think my wife's dead,'" Lamb recalls. When she offered him the phone to call 911, he declined, she says. Keeping his hands in his pockets, he told her, "I can't touch the phone," and asked her to place the call. As Lamb dialed 911, Abshire raced back to his wife lying in the road, which he had blocked with the motorcycle.

About that time, Ruffner, the first awakened neighbor, says he walked to the road where he says Abshire was kneeling next to Justine.

"He said, ‘A car hit my wife, killed her,'" Ruffner recalls. Then, Ruffner says, Abshire asked him a question.

"He said, 'Can you check her, see if she's dead?"

Untrained in either CPR or first aid, Ruffner– who adds he could see no visible injuries on Justine's body– declined to check, and he waited several minutes for the rescue squad to arrive while Abshire remained kneeling beside Justine.

Investigation begins

Although the initial accident report attributes the death to hit and run, officials were immediately suspicious, according to a Virginia State Police agent who began the investigation that day.

Police were particularly concerned about the absence of any skid marks or broken glass, typical signs of a hit and run. The autopsy would reveal further surprises.

As first revealed on ABC, Justine suffered 113 wounds, 23 to her head alone. Her pelvis was broken in three places. But despite such extensive injuries, neighbors on Taylorsville Road say there was virtually no blood on the street. Several residents describe several small circles of blood visible the next morning on the pavement– each "about the size of a quarter," according to one neighbor.

And there were other things missing: "strike marks" on Justine's body, the signature indicators of a car or truck bumper striking flesh and bone.

In May, State Police announced that they did not believe Justine had been hit by a car– at least not while she was standing. Police wondered if she'd died in another place– and by other means– and been taken to Taylorsville Road.

If true, that theory is difficult to reconcile with Abshire's repeated account of the hours that preceded his wife's death.

It was a normal evening, Abshire says, that began with Justine returning home shortly after 7pm from a late-afternoon graduate class she was taking at UVA. Abshire arrived soon after, following a visit to his mother, who was seriously ill at Martha Jefferson Hospital. The young couple were home together– Abshire says he can't remember how long– when he received a call from the hospital. His mother's condition had worsened and might require the family to make certain decisions, he says, and he needed to be there.

He says he drove to the hospital and remained there until approximately 11:30pm. Instead of going straight home, however, he went to the couple's storage unit on Route 33 in Ruckersville where he'd been storing his motorcycle so, he says, he could trade vehicles and have some time on the bike.

"That's how I relax, and that's how I took my mind off of things," he says. "I dropped my car off and went riding."

When he got home about a half hour after midnight, he says, Justine was awake and wanting to talk. Talking became arguing when Justine wanted to discuss his mother's health and his unwillingness to discuss his feelings about her illness. Abshire says he told Justine that sometimes he needed to be alone, and Justine responded, "Well, maybe I need to be alone, too" and left the house in her 2002 Ford Mustang.

It was a chilly morning, and weather records indicate that the temperature dipped to the mid-30s.

Abshire remained in the house watching television, he says, certain that once his wife calmed down, she'd come home. Although he doesn't know exactly what time Justine left, he says he does know the time she called for help: according to his phone records, it was 1:19am.

Although Justine is described by many who knew her as a timid person with a lifelong fear of the dark– and although Abshire later learned that her car was pulled off the road on a barely inhabited, dark stretch of the road– he says she didn't sound afraid. In fact, he says, she still sounded angry.

"I'm on 618," he says she told him, referring to the route number for Taylorsville Road. "My car won't start. Come get me."

According to Abshire, the call lasted about 10 seconds. He says she hung up before he could ask for any details about her location or the nature of her car problems.

"She was trying to prove a point," says Abshire, "that she could be independent."

According to his own time estimates, he found her sometime between 1:39am and 1:44am. Why so long to cover five miles?

He estimates it took him 10 to 15 minutes to get his shoes, his motorcycle jacket, and find his keys and helmet. But these were just the first of several delays– perhaps perfectly innocent but continuing to fuel official suspicions.

Abshire relates that as he drove down Taylorsville Road he saw something ahead and first assumed it was an animal; but as he approached, he realized it was his wife.

On ABC, he described "cradling her" and tearfully described "talking to her." He tells the Hook he was unsure if she was alive or dead, and adds, "I picked her up and had her in my lap."

After sitting with her in the road for an undetermined length of time– he says he doesn't know how much time passed– and still stunned by his horrific discovery, he forgot he had his cell phone with him and instead left Justine in the road, then began frantically banging on doors.

The 911 call by Amber Lamb was placed at 1:57am– 38 minutes after Justine's alleged distress call and a full 13 to 18 minutes, by Abshire's own estimate, after the discovery of her body.

Acknowledging he has been widely criticized for that delay, Abshire says he wishes he had been thinking more clearly, that he had realized he was carrying his own cell phone, and that he had reacted more quickly. But he says people shouldn't pass judgment unless they have been through such a horror. "I would like to see," he says, "how someone else reacts."

As for the theory that Justine was killed somewhere other than Taylorsville Road and by something other than a vehicle, Abshire is adamant it's not possible, and cites her 1:19am cell phone call to him as proof she was hit by a car on Taylorsville Road.

"You'll never convince me otherwise," he says. "There wasn't time for that."

Other revelations

One key question following Justine's death is the suggestion that her husband might benefit financially from her death. On the Primetime special, Abshire cites a $150,000 life insurance policy as the only money he stands to gain.

Her parents, however, believe the true amount is 10 times higher– a figure that father Steve Swartz attributes to a standard clause in almost every vehicle insurance policy: uninsured motorist coverage, which awards payment for injuries sustained by drivers without auto insurance.

According to Matt Murray, managing partner for the Charlottesville office of Allen, Allen, Allen & Allen, and an expert in insurance law, a person needn't be in or even near her own vehicle for uninsured motorist coverage to kick in. And John Doe drivers— as hit and run drivers are called– are always considered uninsured motorists by the courts.

According to insurance documentation shown to the Hook by Swartz, Justine's policy on her Ford Mustang would pay $100,000. But the big money Swartz counts comes from another vehicle: a dump truck. Why was a kindergarden teacher with no commercial driver's license listed as an insured driver on a 10-ton vehicle?

Abshire, who works as a truck driver, explains that Justine purchased the truck because her credit was better than his, allowing for lower interest rates. He says the truck policy was simply the minimum required for him to drive at Luck Stone Quarry, where he did some of his work.

Abshire says he didn't even know about the uninsured motorist coverage, and says he has taken no steps to collect on any of the policies.

Despite such reluctance, Justine's parents have stepped in to become administrators of their daughter's estate. On Tuesday, August 5, in Greene County Circuit Court, the Swartzes won a summary ruling on their motion to step in after Abshire missed the deadline for submitting her will for probate.

Steve and Heidi Swartz say they hope the information that will now be available to them as administrators will shed new light on Justine's financial situation and on any insurance issues. One thing the parents had already learned is that the couple had nearly $100,000 in debts– most in Justine's name– something they believe could have provided an incentive for a killing.

Abshire, however, says his decision not to fight the change in administering her will is proof that he's not trying to hide anything unsavory about finances or insurance claims. But insurance isn't the only source of possible gain from Justine's death.

Soon after she died, Justine's parents and Abshire both spoke with police and learned that while nothing was stolen from Justine's car, the diamond from her engagement ring was missing. When they thought Justine's death was simply a hit and run, the Swartzes say, they believed the stone had been knocked out. But with other evidence about the nature of Justine's wounds as well as the lack of evidence suggesting a hit and run, they now wonder what happened to the diamond, appraised in its platinum setting for more than $6,000.

Although police scoured the area where she was found, the approximately one-carat stone was never located. Both Abshire and the Swartzes say the ring setting remains with the police. Abshire says he initially called asking if her ring had been found, but when he was told the stone was gone, he felt "It was no longer the ring I gave her," and he has made no further attempt to claim either the setting or her wedding band.

Cad or murderer?

There's no shortage of reasons why some people might dislike Eric Abshire, and he readily admitted to several of them on Primetime.

For one, he revealed that he has had a reputation when it comes to women as "someone who, when he decided he wanted to do something, he did it." By his own admission, even grief didn't dampen his libido. In a conversation secretly taped by ABC between Abshire and Justine's father at a vigil held in Orange County on the one-year anniversary of Justine's death, Abshire admitted that in his grief-stricken state in the weeks following the incident, and after drinking too much, he slept with another woman. While he was married to Justine, however, he insists he was faithful.

He also admits he has a history of violence– but he insists it's only violence against men. Indeed, Abshire has faced several charges stemming from fights outside bars. His claims, however, seem to contradict an emergency protective order taken out against him in Greene County in June.

Filed by the mother of his two children, the order cites reasonable cause to believe he'd committed "family abuse." But Abshire has insisted there was no physical altercation, that he never hurt the woman, and he calls the incident a "misunderstanding." The woman declines comment.

Justine's younger sister, Lauren Swartz, disputes Abshire's claims that he's never harmed a woman. In fact, she says, she witnessed one violent altercation that happened when Justine was living in Harrisonburg over the summer of 2000. Eric and Justine had been dating for about a year, and Lauren was staying with Justine.

When Lauren arrived home from work one evening, she says, she discovered her older sister, "unbelievably upset, crying hysterically." Justine's home phone and cell phone were ringing repeatedly, and Justine told Lauren if Abshire couldn't reach her, "He'll just come here."

"Eventually," Lauren says, "he did just show up."

Hiding behind a door inside, where she could see the arguing couple but Eric could not see her, Lauren recalls the fight escalating.

"Then," she says, "he pushed his way in, grabbed her shoulders, and pinned her up against the wall."

At that point, Lauren says, she stepped out and told Abshire to leave, which he did.

Abshire denies all of Lauren's allegations. "It's a flat-out lie," he says.

True or not, it's a he-said, she-said situation and will remain so, especially since Justine can't give her version of that fight. But even if Abshire is a cheater and a beater, does that make him a murderer?

Justine's parents say that what they've learned about their son-in-law since their daughter's death doesn't please them. But they say it's the steady accumulation of details that don't quite ring true that make them wonder about his ability to commit murder; it's the impossibility, they claim, of his version of events the night Justine died.

From their shy daughter's decision to leave the house in the middle of the night to her alleged 10-second phone call asking for help to the evidence– or lack thereof– at the crime scene, they say their doubts have escalated.

Other elements of the case fueled their suspicions. These include the fact that Justine was found without a coat– it was left behind in her car, along with her purse and keys. And that her Mustang– which she allegedly told Eric had broken down– started up immediately when State Police checked it. Two independent mechanics could find nothing wrong with it, according to Jones.

And then there's the mystery SUV. The vehicle that Abshire test-drove in the weeks before the incident on Taylorsville Road was stolen from the dealership days before her death only to surface in a vacant storage unit about a mile from the scene a few weeks afterward. If authorities know what to make of that, they aren't saying.

The Swartzes are not the only ones who believe that Justine didn't die on Taylorsville Road. Neighbor Ruffner says not only did he not hear anything before Abshire knocked; he can't imagine that anyone walking on the stretch of road in front of his house would have been unable to see or hear an oncoming car– even in the middle of the night. The full moon coupled with the ever-lit pole light at the edge of his property made the street fully visible that night– both for Justine and for any oncoming driver.

Abshire says he knows much of the story doesn't make sense, but he defends his innocence– and he's not alone. His brother, Jesse Abshire, arrived at the scene of the accident soon after the first rescuers had responded.

Abshire says an early-arriving firefighter called Jesse at Eric's request, using Ruffner's phone. On Primetime, Jesse denied any involvement in the crime, insisting he was home in bed with his fiancé and baby when the call came in that Justine was dead. He described his brother as a loving husband, "bawling like a baby" over his wife when he arrived on Taylorsville Road that night.

Progress?

As the second anniversary of Justine's death approaches, Steve and Heidi Swartz say they are more determined than ever to see justice served. The $50,000 reward they posted last spring still stands. They handed out blue "Justice for Justine" bracelets on the Downtown Mall on Friday evening, August 8, and say the warm response they received gives them strength to keep going.

Abshire, however, is not making such public pleas. After an initial series of television interviews in which he promised to do "whatever it takes" to find the person or people responsible, he backed away from the public eye until his Primetime appearance.

To those– Justine's parents in particular– who wonder what he has done to try to find his wife's killer, and why he hasn't made more frequent media appearances or commenced his own investigation– as he once publicly promised– he says there's nothing sinister and that his silence is not an indication that he has anything to hide.

Instead, he says, it's because no matter how many times he responds to questions, his answers never satisfy the police, Justine's parents, or the public.

When he first realized police considered him a suspect (though police decline all comment on potential suspects), he says he consulted a lawyer who advised him against taking a lie detector test and told him to stop answering the same questions.

Even an innocent man, he says, can be trapped into inconsistencies that can later be used against him. Still, Abshire says, he has cooperated with police every time they've asked him to— and on the Primetime program, Special Agent Mike Jones of the Virginia State Police agreed that Abshire has cooperated. But, Jones noted, "He could cooperate more."

As for the media, Abshire says earlier coverage– much of it in this paper– was unbalanced and seemed "out to get him." He declined comment for each of the first several articles published by the Hook. "I felt like they were trying to get shock value," he says.

When asked about his life following Justine's death, he looks away and his eyes water. "I've lost everything," he says quietly. He no longer worries what people think of him, and his sole purpose, he says, is caring for his two daughters, trying to shield them from the scrutiny and suspicion he fears will always be there.

"I don't believe this will ever get solved," he says. "Short of someone jumping up and down and saying, ‘I did it,' this is a cloud that will be over me for the rest of my life."

#