COVER- Obscene! (sort of)- Staunton porn trial bizarre from start to finish

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

STAUNTON–- It was a scene straight out of The Andy Griffith Show's fictitious town of Mayberry. On Tuesday, August 12, just before the judge gaveled Staunton Circuit Court into session, smiling citizens reporting for jury duty waved hello to each other, some exchanging familiar back-slapping greetings with sheriffs, and the city prosecutor inquired about a potential juror's recent fishing trip. It was just another day in the small Southern town of Staunton. That is, until jury selection in the town's first obscenity trial in recent memory got underway.

"Would you avoid a movie if you knew it contained sexually explicit material?"

"When was the last time you viewed an adult movie?"

"You will be asked to view depictions of sexual acts of all varieties: vaginal, anal, oral sex, sex with multiple partners, ejaculation on the faces of women. Do you think you could do that?"

It was that kind of week in Staunton, where prosecutors tried the first local obscenity case in recent memory against 10-month-old After Hours Video, its owner, Rick Krial, and cashier Tinsley Embrey.

The court asked a four-man, three-woman jury to listen to the testimony of police officers and experts and watch two DVDs that undercover police had purchased just after the store opened last October: Sugar Britches and City Girls Extreme Gangbangs. It was a trial unlike any Staunton, and maybe Central Virginia, has ever seen, and the jury placed an exclamation point on the weirdness by coming back with an equally unusual verdict.

Dramatis personae

If, as Shakespeare said, all the world's a stage, then last week this courtroom was the Globe Theater. All the major players looked, sounded, and acted as though they could have come straight from central casting.

Defendant Rick Krial, After Hours Video's owner, with his neatly cropped goatee and piercing blue slits of eyes, wore black suits, loose ties, and the same stony expression of a hard-nosed businessman unfazed by this attempt to shut down his enterprise.

Co-defendant and cashier Tinsley Embrey played to a tee the part of the hapless accomplice. Twenty-eight years old and with a blonde beard, he wore suits too big for his large frame, making him look like a 12-year-old kid waiting head-in-hand to see the principal for his latest transgression, unsure exactly why he's in trouble.

Their lawyers, Paul Cambria and Louis Sirkin, having made names for themselves defending the likes of Hustler publisher Larry Flynt, goth rocker Marilyn Manson, gangsta rapper DMX, and countless others who have walked the tightrope between bad taste and obscenity, looked precisely like big shot, out-of-town defense attorneys in designer suits and with large, shiny watches, carefully manicured hairstyles, and, occasionally, knowing smirks.

For the prosecution, Staunton Commonwealth's Attorney Ray Robertson couldn't have been more unlike his opponents. Sporting plain blue suits more Sears than Armani, with a round pallid face suggesting a summer vacation closer to the Blue Ridge than the blue Caribbean, and speaking in a high tenor with a distinctly Shenandoah Valley accent, Robertson was as unvarnished as his opponents were smooth.

Assisting Robertson was Matthew Buzzelli, a federal prosecutor on loan from the Justice Department's obscenity task force. His tall frame, broad shoulders, and pronounced jaw-line telegraphed the imposing stature of a legal eagle working for Uncle Sam.

And presiding over it all: Judge Thomas Wood, hauled out of retirement to try the case because the regular Staunton Circuit Court judge didn't have room on his docket to deal with the unusually high number of briefs and motions. This three-ring circus required a stern ringmaster, and Wood proved up to the task. With his white hair and craggy visage, he looked and sounded like the man Fred Gwynne studied to play Judge Chamberlain Haller, the gruff, no-nonsense, play-no-favorites, small town jurist from My Cousin Vinny, right down to beginning sentences with phrases like, "I'm not sure how you're used to doing things, but here..." and ending with phrases like "...even though you're driving me crazy."

With characters like these, the trial quickly turned into the kind of real-life legal drama that's given rise to countless Hollywood productions. Except this time the fate of two real men hung in the balance, and this story rarely stuck to the script.

Unlucky seven

Usually, jury selection for a misdemeanor trial is completed in a matter of minutes once it's been verified that the assembled citizens have no personal ties to any of the parties involved, and there's no other reason why they can't give the defendants a fair trial.

In this case, it took almost two days.

That's mostly because attorneys in this case opted to screen jurors one by one. This process– known as voir dire– is usually reserved for capital cases, but because of the touchy subject matter, attorneys wished to question potential jurors out of earshot of the others.

"This is totally typical for anyone who's ever had one of these cases," said defense attorney Cambria. "Usually it takes two or three days, and I've had one take as long as 38 days. I think both sides agree this is the way it should happen."

Prosecutor Robertson wasn't quite so used to it.

"I'm not saying it's wrong," he said, "but I've never seen anything like this, and I've been practicing criminal law since 1968."

While Robertson had relatively few questions other than pressing citizens on how they felt about pornography and people's right to consume it in general, Cambria and Sirkin got quite personal, asking each citizen about his or her x-rated viewing habits.

"I viewed as many as four or five in the early '90s," said one middle-aged woman.

"I saw one about 60 years ago," said one 79-year old man. "That was back when you had to buy film and a projector."

"Yes, when I was in the Navy," one 39-year old man admitted.

"Where did you get them?" inquired Sirkin.

Without missing a beat, the man replied, "It's the Navy, sir."

For a total of ten hours over two days, both sides in the misdemeanor trial vetted 27 potential jurors for their impartiality. It didn't take long for it to become clear that finding enough jurors who could leave their biases at the courthouse door would take a while.

"I would have a hard time dealing with it," said one middle-aged woman, "because it's so totally against any belief of mine that people can buy this stuff and watch it."

"I have a bias for After Hours Video," another man in his 20s explained to the judge. "I don't have anything against [pornography], and I can't say I would be able to follow your instructions."

And if that weren't enough, loaded questions made the screening process longer. At multiple points throughout the day, Judge Wood called out both sides for attempting to make its case before the trial began.

"Do you understand," asked Robertson of one woman, "that if we excused everyone that felt that this stuff made them uncomfortable we couldn't get an accurate cross-section of the community?"

Before the woman could answer, Wood interjected, "Is that a question?"

Hours later, Wood reprimanded Sirkin for implying that other stores in Staunton sold equally sexually explicit material. After Sirkin apologized for inserting evidence into his question, an agitated Wood replied, "It doesn't do any good to say you're sorry after you've already asked the question."

Finally, Wood had had enough.

"Okay," he said. "You have both tried to indoctrinate these jurors, and you need to stop doing that and start asking questions."

By 2:15pm Wednesday, August 13, the final jury consisted of four men and three women, including a factory worker, a housewife, a retired Staunton firefighter, a special education teacher, a retired salesman originally from New Jersey, an administrative assistant at a travel agency, a human resources recruiter, and a truck driver. All but one of the jurors was over 50. All but one identified local churches where they regularly attend Sunday services.

However, despite their backgrounds, all insisted they could view the pornographic material in its entirety in the name of civic duty. They would have to apply a three-prong test to determine if the material was obscene– and thus unprotected by the First Amendment. The jury would have to consider the DVDs "as a whole" and determine if each movie had "as its dominant theme or purpose an appeal to the prurient interest in sex, that is, a shameful or morbid interest in nudity, sexual conduct, sexual excitement, excretory functions or products thereof, or sadomasochistic abuse, and which goes substantially beyond customary limits of candor in description or representation of such matters and which, taken as a whole, does not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value."

Soon, they would find out what a challenging task that would be– especially when they had to do it in open court.

A shaky start

The trial of the century nearly ended three minutes after it began.

"Mr. Embrey, of his own admission," Robertson told the jury during his opening statement Wednesday afternoon, "told the police investigator that Krial had hired him to sell porn and run his Staunton store."

Cambria immediately rose to object and requested to speak with the judge with the jury out of the courtroom.

"He's now told the jury an alleged statement by [Embrey] not subject to cross-examination," said Cambria. "I move you declare a mistrial."

For 35 minutes, Wood consulted several books of case law and Virginia code, and it looked as though the judge might throw out the whole case on Robertson's technical slip-up. In the felony cases Robertson usually argues, prosecutors are allowed to allege a conspiracy between two defendants without an actual conspiracy charge against either defendant. The legal question hinged on whether Robertson could allege a conspiracy between Krial and Embrey in this misdemeanor trial.

Finally, as the gallery held its collective breath, Wood was ready to rule.

"I'm not going to declare a mistrial," he said to Robertson, "but I don't know what's going to happen if you don't have the evidence you say you're going to have."

With that, the jury returned— only to be escorted back into the jury room seven minutes later.

Such seating and unseating of the jury proved frequent, as each side often wished to make a legal argument out of earshot of the seven who would decide the case. Of the three-and-a-half hours of proceedings on Wednesday, the jury was privy to only 97 minutes, as each side pulled out all the stops to gain every last inch on the opposition. Yet, as the motions became increasingly absurd, Judge Wood acted as a sort of Greek chorus, voicing what those in the gallery could not.

When Robertson wanted to introduce photographs police took of the inside of After Hours Video on October 29, 2007— two weeks after undercover officers purchased the two DVDs in question— defense attorney Sirkin asked, "What is the relationship between what the store looked like on the 29th to what it was on the 15th?"

"Are you going to introduce evidence that the store looked different two weeks later?" Wood asked.

When the defense continued to press the point, Wood indicated he'd heard enough.

"We're not talking about Macy's with five floors!" he said, his booming baritone pushing its upper register. "If it's an accurate portrayal of what the store looked like on the 15th, I'll allow it."

Not that the prosecution was safe from Wood's scorn. At one point, Robertson expressed concern that the defense could introduce other, more popular adult movies sold in Staunton as evidence of what's acceptable by community standards, including Deep Throat, The Devil and Miss Jones, or Debbie Does Dallas.

Robertson wished to make an important distinction.

"These movies have got plots!" he protested.

Before Robertson could say another word, Wood nearly jumped out of his chair.

"It's people having sex with each other!" he shouted, pounding his fist on the bench. "Don't tell me that these movies aren't the same type of movie!"

For all the unusual legal motions on Wednesday, the trial was about to get a lot stranger on Thursday.

Commonwealth's XXX-hibits

For three hours and 33 minutes, the jury watched an unrelenting series of sex acts on a projector screen, while all anyone in the gallery could do was watch the looks on the jurors' faces and listen to constant, tea kettle-like screams reverberate off the wood-paneled walls of the courtroom.

The jury's discomfort was apparent from the first moan. The men shifted in their seats every few minutes, covering their mouth or holding their face in their hands, hiding their full expressions from the rest of the court. At least two of the four turned a deep purple as the moans grew more shrill and the unmistakable sound of flesh slapping flesh grew more rapid. The women, all over 50, sat stone-faced, their expressions ranging from annoyance to disgust.

"That was very disconcerting," says one juror who spoke to the Hook on condition of anonymity whom we'll call Mr. Jones. "Who wants to be stared at for four hours while all anyone out there could hear were grunts and groans?"

But as the day went on, jury's distaste quickly gave way to boredom. Jurors yawned, chewed their nails, picked their teeth, checked their watches, and exchanged raised eyebrows, as if to say, "There's more?" One even dozed off for a second before reviving himself, aware that a nap, however brief, could mean a mistrial.

Not that there was much to hold the jury's attention. Sugar Britches features no musical score, and no pretense as to why the two people are having sex— not even a pizza delivered or a pool to be cleaned. It takes 25 minutes to get to the first line of dialogue: "Oh, yeah!" Not a single polysyllabic word is uttered for the entire hour and 46 minutes, unless "yeahyeahyeahyeahyah!" counts.

Perhaps, though, the jury caught their case of the yawns from the defense. At different points throughout the movies, Cambria and Sirkin both arched their necks, opened wide and yawned without so much as covering their mouths. Defendant Embrey nearly nodded off multiple times, looking less like a 28-year-old man watching porn and more like the 12-year-old boy trying to stay awake in math class.

Asked– once court adjourned– about these long, gaping yawns, Sirkin said simply, "Human sexual activity after three hours gets boring."

According to Jones, the jury didn't need much convincing on that point.

"That was the most boring four hours of my life," he says.

Meanwhile Robertson watched intently, fixing his eyebrows into a permanent scowl, shifting his gaze back and forth between the screen and the laptop playing the DVD. At one point, he bowed his head and almost appeared on the verge of tears.

Robertson's co-counsel Buzzelli hunched his tall frame into a contemplative crouch, never once looking at the display he later called "prurient, morbid, and unhealthy."

Judge Wood rubbed his eyes and blinked frequently, as if trying to wake himself up from a bizarre dream.

The jury returned from lunch at 2:31pm to watch City Girls Extreme Gangbangs. This selection offers a little more narrative. The premise? Guys recruit girls to have group sex in a movie. The film seemed to have a cinema verite motif with improvised overlapping Altmanesque dialogue above a soundtrack that sounded like a collaboration between German technophiles Kraftwerk and '60s swingers Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass.

For most of the movie, Jones says, the only thing that offended him was the low production value.

"It looked like they just hired four hookers and shot it in a warehouse," he says.

Finally, at 4:18pm an actress screamed out for her partner(s) to, er, finish "on my f***ing face!" and (spoiler alert) evidently someone complied with the request, for so too did the movie finish. At that point, Wood called for a brief recess, during which several gallery members stepped out for a cigarette and, because it was raining, a shower.

However, watching all the naughty material almost ended up for naught. When the jury returned, the prosecution called as a witness Dr. Mary Anne Laydon, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist specializing in rehabilitating the victims and perpetrators of sex crimes, and perhaps a welcome change of pace for the jury, considering that she was a woman wearing clothes. When Buzzelli asked Laydon to evaluate a still image from Sugar Britches, she testified, "The female has no pubic hair, no breasts, an angular body type. Typically this is someone whose body has not yet fully developed sexually. In most industrialized countries, this occurs at the age of 12."

Cambria sprang up to object.

"Right from the beginning," Cambria said, "the Commonwealth has tried to make this an underage case. They have no proof and no good-faith basis to allege that any one of these performers is underage, and I move for a mistrial."

Buzzelli, having made this argument in federal court before, protested vehemently.

"It speaks for itself, that girl is clearly made to look like a child!" he said.

Robertson went one step further.

"It's no accident she looks the way she does," he said. "This film does appeal to pedophiles. Pedophiles will buy this film and get off on it!"

Wood wasn't buying it.

"Give me a break!" he said. "You're saying she's like a child because she has small breasts? I saw these movies; every one of these women was shaved!"

When Buzzelli and Robertson continued to argue the point, Wood sternly warned them, "If your witness makes this sound like a kiddie porn film, we're going to have a mistrial."

Buzzelli later expressed his disappointment with the ruling, calling the federally maintained database verifying the ages of porn performers "a joke."

"It's one FBI agent, probably based somewhere near Los Angeles, responsible for monitoring thousands," he told the Hook. "I've seen these records. They're photocopies of Portuguese drivers' licenses and Chinese passports that you can barely read. The federal government does not track it. It is an un-enforced law."

After a long conference with the prosecutors, Laydon finally returned to the stand to offer her professional opinion that such acts as "inserting two penises into one vagina" and "removing the penis from the female's anus and putting it in the mouth of the female" are "risky behavior."

The Commonwealth rested at 5:30pm.

The final act

When the case re-opened the morning of Friday, August 15, the day began as the previous day had: with attorneys for both sides arguing various motions and Judge Wood ruling on them. Just after 9am, Wood was ready to ask the jury to enter when Cambria rose to say one last thing.

"Just so you're not surprised, Your Honor, when the jury comes back in, the defense rests."

A ripple of whispers could be heard throughout the gallery of nearly 40 Stauntonians who had turned out for the final day of the trial.

No expert testimony from witnesses. No evidence showing community standards. No case. The defense did not dignify the prosecution's case with a response.

"We didn't feel that they proved their case," Cambria later told the Hook. "They didn't prove anything about community standards. They just kept harping on this child thing, and we thought the jury would be able to sort that out."

So, after an hour of attorneys hammering out jury instructions in the judge's chambers, the jury sat for closing arguments. Law & Order couldn't have staged it any more dramatically.

Leading off was Buzzelli, who towered above the jury box invoking James Madison and Abraham Lincoln and pleading with the jury to make a decision "to promote the general welfare."

"You know, my father always said, ‘Matt, keep an open mind, but not so open that your brains fall out,'" he said, adding, "The defendants gambled. They came into this town and thought no one would care. Well, someone did. Mr. Robertson cared, and now he gives this case to you."

With many dramatic build-ups and decrescendos, Cambria showed no less zeal in making his client's appeal.

"This country is all about individual rights in a community in 2008, not 1958," he said. "If I put a picture from Playboy on a billboard along Route 250, that would exceed community standards. But if I choose to purchase one of these DVDs, take it home, and watch it in the privacy of my home, no reasonable adult would say that's unacceptable under the circumstances."

Cambria even used the city's "adult business licensing and zoning statutes" passed by City Council in December to prevent businesses like After Hours from opening as proof that Staunton accepts such enterprises.

"It's acceptable because they license it," he said. "They collect money for that license! If nothing else, that's proof that the community accepts this material. That's like you getting your driver's license, driving home, and then when you get there they arrest you because they say you're not allowed to drive! What the heck's the license for?"

Jones says the adult license was not much of a topic of discussion, but, rather, the fact that Staunton officials licensed the store in the first place when it opened in October.

"We wanted to punish the City of Staunton for licensing this place that wanted to sell DVDs without asking what kind of DVDs they wanted to sell," says Jones. "It's like if someone wanted to open a tobacco shop, I would ask if they were going to sell marijuana. So, it seemed to us that Robertson was under a lot of political pressure to do something about it, after the city screwed up."

Finally, Robertson had the last word, and with it he reminded the jury just what they had watched 24 hours before.

"There was a guy having sex with a girl in her vagina and another guy having sex in her anus," he said. "There were two guys with their penises in the same vagina. If we're influenced by what we see, what do you think that does to a town?"

And then Robertson made a fervent plea to his fellow Stauntonians, calling the privacy defense "the biggest red herring" and urging them to think of the consequences of their verdict beyond the courthouse walls in "the town we love so much.

"These people," he said, without specifying whether he meant the defendants or the not-from-around-here attorneys representing them, "are coming in here and telling you what the community standards are. You know what the community standards are!

"If you want this stuff," he continued, "go buy it where they don't care about morals and decency, but don't turn Staunton, Virginia, into Las Vegas."

Then he lowered his voice to a near-whisper: "Staunton may be a small light shining in the darkness these days, but don't put it out," he said. "Let it live."

Just when it seemed over, Robertson raised his voice to leave the jury with one more thought: "And let it maybe be the first domino that reverses this junk!"

After a break for lunch, the jury returned to deliberate at 2:05pm. Embrey shared a few laughs with friends who had come to support him, telling about how Larry Flynt had once paid a fine in Ohio court with $1 bills he collected from the waistbands of strippers he employed. Krial told the group he'd rather be alone, and went outside to smoke a cigarette while awaiting his fate.

Then, one hour and 44 minutes later– approximately the time it took the jury to watch Sugar Britches– a sheriff announced the jury had reached a verdict.

Krial steeled himself with a big breath. Embrey closed his eyes.

Staunton Circuit Court clerk Thomas Roberts read the verdict.

"We the jury, on the count of obscenity, City Girls Extreme Gangbangs, find the defendant Rick E. Krial guilty."

Krial sighed and bowed his head, his expression unchanged. Embrey rubbed his face in disbelief.

"We the jury, on the count of obscenity, City Girls Extreme Gangbangs, find the defendant Tinsley William Embrey not guilty."

Embrey looked skyward, and let loose a sigh of relief from his barrel chest.

"We the jury, on the count of obscenity, Sugar Britches, find the defendant Rick E. Krial not guilty."

Murmurs of confusion filled the room. Roberts repeated the verdict, perhaps to assure even himself that he had read it right the first time. He then read that Embrey was not guilty for Sugar Britches as well.

The cashier was not guilty, the owner was guilty– but for only one of the DVDs. The jury fined Krial $1,000 and his company, After Hours Video LLC, $1,500.

Krial declined comment after the jury rendered its verdict, except to say, "We're going to place our appeal."

Embrey told reporters that while he was pleased to be off the hook, this was not a completely happy day.

"I'm very happy to be acquitted, but I don't agree with the decision," he said. "I do not agree that Rick Krial or the company are guilty."

Sirkin was equally ambivalent. Though his client, Embrey, was the only one completely exonerated, it was the first time he and Cambria had worked a case together and not emerged victorious.

"I'm happy for 'T.W.'," said Sirkin, referring to Embrey by the folksy moniker he used throughout the trial to refer to his client, "but anytime there's one of these decisions, it takes a bite out of the First Amendment. It's a lovely town, but I would like to think that one day Staunton will catch up to what the world is like in 2008."

Cambria initially seemed dejected. He stared down at his legal pad after hearing the verdict, not even raising his head to argue for his client during the sentencing phase, leaving that to a Staunton-based co-counsel. But by the time he faced reporters, he did his best to put on a brave face.

"I do think it's interesting that for the first time, there's been a sanction of adult material in this community," Cambria said, referring to the not guilty verdict on Sugar Britches, "but it's unfortunate they split the hair."

Days later, the Hook reached Cambria by phone and asked if he had any regrets about not putting on a case in rebuttal to the Commonwealth.

"Never," he said. "They didn't prove their case."

The only one to not express mixed feelings was Robertson. He greeted reporters beaming, suit jacket off, tie loosened, cheeks ruddy with the rush of his partial victory.

"I'm elated," he said, "that the people of the City of Staunton have spoken on behalf of their friends and neighbors and spoken out about how they feel about this stuff."

So what was the difference between the two movies? While neither the Hook nor anybody else in the gallery saw the movies, counsel for both sides agree there was one important difference.

"The jury felt that the tape that didn't contain multiple partners was not obscene," said Cambria. "It seems to me that's a lot of why the jury decided the way they did."

"My best guess is they drew a line with Sugar Britches since it was all one on one," Robertson agreed.

Sirkin was baffled by this logic.

"I don't see what the difference is," he said, "between two people doing one act, and three and four people doing the same act."

According to juror Jones, that's only part of the story. He says one scene at the end of City Girls Extreme Gangbangs made the difference.

"A series of gentlemen was performing anal sex on a woman," says Jones, "and then without cleaning himself or wearing a condom or anything, proceeded to have her give him oral sex. And they did this six or eight times."

Says Jones, the obscenity of this scene required no debate among the seven jurors.

"When I was in the Navy, I saw all kinds of pornography all over the world," he says. "This was beyond anything I'd seen. We figured you couldn't show that to your next-door neighbor without him thinking you're some kind of deviant. It was the difference between a mountain stream and Niagara Falls."

Sequel in the making?

The guilty verdict now opens the door to more trials against Krial and Embrey. Robertson still has 10 more DVDs Staunton undercover police purchased from After Hours Video in October 2007, and he indicated that this would not be the end of his campaign against the store. Krial would likely face felony charges, now that this first misdemeanor conviction makes him an alleged repeat offender.

"I'm confident we'll have the same sort of stuff," he says, "and that the jury will find it equally, if not more, gross."

Cambria expresses optimism that he can successfully appeal Krial's guilty verdict.

"From what I'm hearing," he says, "this constant theme of 'children, children, children' got through. You even heard it in final summation when he was saying this could get in the hands of minors. Usually, that's a depth charge and it means either a mistrial or a reversal. It always corrupts a case, and I've had judges declare a mistrial for less."

Cambria has moved that Judge Wood set aside the jury's verdict, a motion that grants at least 60 more days before After Hours has its business license revoked as a result of the conviction. If that fails (and Robertson says no judge has ever set aside one of his convictions), Cambria will file his appeal and attempt to make a case to the Supreme Court of Virginia for a re-trial.

There is one thing that Cambria can say for sure: "The last chapter in this book has yet to be written."

When asked what he thought of Cambria's vow, Robertson says, "Hey, that's fine. Bring it on."

Given the drawn-out, often uneasy procession of this first trial, many a Stauntonian may echo a sentiment of Judge Wood's. Leaving his chambers on Wednesday, Wood passed by reporters and muttered two words to nobody in particular:

"Jesus Christ."

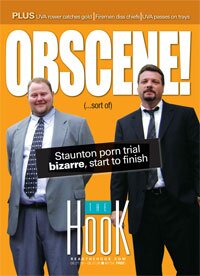

Cincinnati-based obscenity lawyer Louis Sirkin (left) and his Buffalo counterpart Paul Cambria (right) have teamed up on numerous occasions, including to defend Hustler publisher Larry Flynt. Until last week, this legal dream team had never before lost a case.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Staunton Commonwealth's Attorney Ray Robertson (right) mulls strategy with co-counsel Matthew Buzzelli (left), a prosecutor with the Justice Department's obscenity task force.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Judge Thomas Wood frequently reined in attorneys from both sides. When one tried to distinguish the two DVDs at issue from more popular X-rated fare like Debbie Does Dallas, Wood shouted from the bench, "It's people having sex with each other!"

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

After Hours Video cashier Tinsley Embrey awaits his fate outside the courthouse.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Shop owner Rick Krial (second from left) and cashier Embrey waited an hour and 44 minutes for a verdict. The two could now face felony charges for 10 more DVDs undercover police purchased in October 2007.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Despite being the only defendant to be completely exonerated, Embrey was not all smiles talking to reporters about his mixed feelings about a mixed verdict.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Though Robertson won only two of a possible six convictions, he was not shy about claiming a victory for "morals and decency."

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

#