COVER- The diplomat: Piecing together Casteen's longevity

John Casteen

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY GABRIEL ROBINS

It's a wonder the offices of college presidents aren't outfitted with revolving doors. Among U.S. News and World Report's top 50 universities, the average president has been in the top seat for just six years– only long enough to see three classes of undergraduates move from matriculation to commencement.

In that top 50, no president has served longer than John Casteen. This month marks his 18th year at the helm of the University of Virginia.

Yet, unlike some high-profile college presidents who encounter controversy, Casteen appears never to have had to fight to keep his job– but it's not as though he hasn't had his share of controversies:

In 1993, despite having wooed his second wife when she was a young teaching assistant, he approved a ban on student-faculty romances.

In 1994, despite having touted the student-run nature of the Honor System, he helped overturn a conviction after a legal threat.

In 1998, the heralded UVA Medical Center sent two babies home with the wrong mothers.

In 1999, despite probably kissing off any future donations from the founder of FedEx, he suspended Fred Smith's son for a violent on-campus attack.

In 2003, having endured decades of the Virginia Pep Band offending opposing schools at football games, he banned the decades-old, orange-vested scamps from all future athletic events after the Governor of West Virginia took umbrage at one of their halftime displays– even when the Rector of the Board of Visitors had winked at the Pep Band's crimes.

And in 2006, after allowing students and faculty members protesting pay rates to squat in his Madison Hall office for nearly a week, he called the constables and had them arrested.

The arrests of the "Living Wage" protesters certainly upset the left, but Casteen was slammed by the right as well. FoxNews host Bill O'Reilly, for instance, called for his head after the Cavalier Daily published cartoons that many Christians found offensive.

But bigger controversies were brewing.

BY COURTENEY STUART

Since it was formed in June, the so-called Amethyst Initiative [see this week's news section] has garnered the signatures of 128 university presidents who believe it's time to reconsider the 21-year-old drinking age and calling for an "informed, unimpeded debate." One signature you won't find there– at least not yet– is that of UVA's John Casteen.

In an August 23 speech to the parents of incoming freshman, Casteen did one of things he does best: sidestep controversy.

This time, he dodged a possible hornet's nest by saying he'd refrain from signing the Initiative for now but that he'd reconsider signing if Initiative backers "are able to develop and publish the evidence to prove there's not a negative difference in the impact on young people."

In other words, Casteen might sign the Initiative– but only after the debate the Initiative is calling for has ended. Ever the diplomat.

The revolving door

Being the president of one of the country's top universities means navigating a minefield of potential gaffes.

In 2001, Harvard University president Lawrence Summers arrived in Cambridge with a gleaming resumé, fresh from overseeing one of the most prosperous economic periods in American history as Secretary of the Treasury under President Bill Clinton.

Five years later, the Harvard faculty delivered Summers a vote of "no confidence" after he remarked that men might be innately more suited than women for success in engineering and the sciences. Summers resigned less than a year later.

In 2005, the College of William & Mary heralded as its new president Gene Nichol, a man with successful tenures as dean of the law schools at the University of Colorado and of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Under his leadership, the numbers of applications for admission and dollars pledged to the college's capital campaign reached record highs.

However, after removing the cross from Wren Chapel in an effort to make the space more friendly to other religions, and allowing a student group to bring a touring production called the "Sex Workers' Art Show" to campus, Nichol was forced by the Board of Visitors to resign in February.

The University of Richmond axed its president last year for referring to some student brains as "mush."

Casteen's predecessor, Robert M. O'Neil, now head of a notable free speech center, lasted just five years at UVA.

But there's the still-ticking, 64-year-old Casteen, living in the president's house at Carr's Hill where he's resided since he took the job when he was 46. What's the secret of his longevity?

"He has an uncanny ability to sidestep controversies," says UVA politics professor Larry Sabato, a member of the faculty since 1977. "He holds his tongue and keeps a low profile, but he also knows how to act before it's too little too late."

Indeed, in the infamous Richard Smith case, Casteen stayed on the sidelines while the scion of the FedEx fortune was permitted to remain on campus despite an assault conviction. Only after 300 students protested on the Lawn in 1999 did Casteen oust Smith, who had broken a student's jaw in a random three-on-one attack.

"I think he's understood never to get too excited about things," says former James Madison University president Ronald Carrier, speaking from 27 years of experience running a large Virginia public college. "You have to look at the long term and not just the short term issues that may create a lot of controversy but detract from the mission."

Casteen parlayed a career that began as an English scholar and UVA admissions dean into learning the political ropes as Governor Chuck Robb's secretary of education, and then president of the University of Connecticut– each step along the way developing the political skills necessary to walk the UVA tightrope for so long.

However, Casteen received an education of his own early in his presidency– once when he shone light on a scandal that cost five popular university officials their jobs, and another when a university president down the road found out how the chief executive– even if he's been ensconced in the president's office for decades– can become unpopular with the stroke of a pen.

'A sad day'

When John Casteen returned in 1990 from the presidency of the University of Connecticut to hold the same position at his alma mater, the athletics department had changed a lot since he last worked for UVA as dean of admissions in 1982.

Though Ralph Sampson had graduated seven years before Casteen's ascendance to UVA's highest office, the 7' 4" athlete continued to cast a large shadow over Grounds. The basketball legend had put Charlottesville on the collegiate athletics map, success that head coach Terry Holland built upon throughout the '80s. In 1984, the year after Sampson left, the men's basketball team made the NCAA Tournament's Final Four, made another run to the Sweet 16 in 1989, and sent six players to the NBA in the post-Sampson era from 1984 through 1989.

The one who capitalized on this success more than any other was Ted Davenport, an alum, basketball fan, and veteran executive director of the Virginia Student Aid Foundation, a fundraising organization he ran independent of the athletics department.

Davenport was the center of what media reports blasted as an ol' boy network of athletics boosters, and so Jim Copeland, a former offensive lineman for the Cavaliers' football team, returned to Grounds in 1987 with a two-pronged mission.

"It was important to me," Copeland says, "that our kids graduate on time and that our program be run ethically."

To achieve his clean-up goals, Copeland began looking over the shoulder of Davenport and the rest of the VSAF. Davenport and company were not inclined to knuckle under to Copeland. Not only did they perceive Copeland as a "football guy," but they were still smarting from the fact that their man Holland had been denied the AD job. Copeland further ruffled feathers when he demoted Davenport, ending his 30-year run at the head of VSAF.

Two years after Copeland's arrival, Holland left UVA in 1989 to become the AD at Davidson College in North Carolina.

This was the situation Casteen faced when he arrived in 1990. Casteen and Copeland already vaguely knew one another. In the mid-'60s, while Copeland was in the gridiron trenches, Casteen was elsewhere on Grounds earning high honors in English. While it remained to be seen what if anything Casteen would do to mediate the tension between Copeland and his detractors (some of whom sat on the Board of Visitors) one thing was clear to then-James Madison University president Ronald Carrier.

"He's always understood the role of athletics for alumni giving," Carrier says, himself having overseen JMU's development into a basketball powerhouse in the Colonial Athletic Association. "It's hard to balance that with academic concerns sometimes, but it's essential, especially in the ACC."

But Casteen would soon find out that some alumni were perhaps a little too giving.

In 1991, new VSAF head Lawson Drinkard discovered that certain boosters had made several no-interest loans to UVA athletes. Casteen recommended Drinkard investigate further. By April 1992, Drinkard issued a scathing 550-page report that revealed that the VSAF had made loans totaling $14,948.98 to 30 athletes between 1982 and 1990.

While the loans– which averaged just under $500 each– broke no laws, they ran seriously afoul of the rules in the world of college sports.

That's been the case ever since the NCAA found that Southern Methodist University in Dallas had given $61,000 to 13 players. As punishment for this violation, NCAA officials issued their one and only "death penalty" sanction: cancellation of SMU's entire 1987 football season, cancellation of all road games for the 1988 season (SMU voluntarily canceled the home games), and a ban from all bowl games until 1990. SMU won three national championships before the punishment. Since the axe fell, they never gone to a post-season bowl game.

A grim-faced Casteen announced the results of the Drinkard report at a rare Rotunda press conference. "I'm sorry to say," he said, "that the conclusions of this report make this is a sad day in our history."

Casteen called the VSAF's actions "indefensible," fired Davenport and two other VSAF officials on whose watch the loans were made, and ordered the VSAF to be subsumed under the athletic department, directly answerable to Copeland.

After announcing the dismissals, Casteen, with Copeland at his side, proclaimed, "We are committed from this day to exercise leadership and institutional control to ensure that the highest standards are maintained by the university."

Days later, NCAA executive director Dick Schultz, who had been UVA's AD during the time of the loan, stepped down.

Ultimately the NCAA sanction was two years' probation, and it docked the Cavalier football team four scholarships over two years. John Casteen had dodged a very big bullet.

Family feud

Far more devastating was the internal damage to the UVA athletics family. Davenport and two former VSAF officials sued the university and Copeland. Many fans sided with the always-popular Davenport, arguing that Copeland could have handled the matter internally and that Davenport should not have been publicly embarrassed, much less fired.

Calls for Copeland's head among UVA fans grew louder. Even Casteen couldn't save him.

Copeland later acknowledged to the Newport News Daily Press, "It's gotten pretty nasty around here," and in December 1994, he decided he'd had enough and accepted another interesting job offer. Impressed by his handling of the VSAF scandal, SMU hired Copeland as AD to rehabilitate its athletics program, a post Copeland held until his retirement two years ago.

Some of Copeland's biggest detractors soon began a public campaign urging that Terry Holland return to the job they believed he should have had in the first place. The campaign– complete with "Bring Back Terry" bumper stickers– was a huge slap in the face to Casteen, who remained silent– until finally bowing to the pressure and hiring Holland (who declined to be interviewed for this story) four months after Copeland's departure.

Thus began a nine-year working relationship between the two men: Holland served as AD until 2001, when he switched gears to become a "special assistant" to Casteen in charge of raising money for what is now John Paul Jones Arena.

Sixteen years later, Copeland stands by his actions.

"There's a process you follow whenever you discover this kind of thing, and we followed that process to the letter," he says. "We were not going to tolerate NCAA violations. It went to the heart of who we were."

And Ted Davenport? Although he died in 2001, he still remains a presence in UVA athletics. In 2002, Casteen helped to re-christen the renovated Cavalier baseball stadium "Davenport Field."

Having watched the scandal from his vantage point in the faculty, politics professor Larry Sabato says the way Casteen handled the potential disaster and its fallout is a vintage example of how Casteen manages to "sidestep" controversy.

"If you look around the country and see how college presidents lose their jobs," Sabato says, "it's generally because they either did too little too late or acted too quickly and too drastically. In this case– as he does in most cases– he knew when something required immediate action, but he also knew that sometimes people get mad about something and it sorts itself out."

Stretching out the welcome mat

Between acting too quickly and not acting fast enough, former JMU president Ronald Carrier was usually more inclined toward the former than the latter, as it was during his 27-year tenure in Harrisonburg that the school exploded from small, formerly all-women Madison College to mammoth research institution James Madison University.

Enrollment tripled, as did the number of faculty and staff. The first doctoral programs were instituted. Twenty new buildings expanded the campus all the way up to, and then across, Interstate 81. By the time Carrier retired, U.S. News & World Report had ranked JMU the top regional public university in the South for three years running.

The parallels between Carrier and Casteen are striking. Each came into his job from a largely successful presidency at another public university, each has overseen expansion of his institution to unprecedented proportions through aggressive fundraising, each has successfully diversified his school's student body through increased availability of financial aid. They have even ignited similar controversies: both intervened in honor trials to overturn an honor board verdict and reinstate a convicted student.

However, while Casteen has rarely tussled openly with any of his faculty, beginning in January 1995, some faculty at JMU became concerned that the man known affectionately around campus as "Uncle Ron" was beginning to get too comfortable.

The first shot sailed across the bow on January 15, 1995 after Carrier announced a massive overhaul of the school's academic landscape, merging most of the College of Letters and Sciences with the College of Communication and the Arts. Math and science departments– except the physics department, which Carrier elected to eliminate– joined the new College of Integrated Science and Technology, answerable to its new dean, Carrier's son Michael.

That night the faculty senate voted 22-3 to condemn Carrier for "the appearance of nepotism": naming his son– assistant provost Michael– to head the new college without what they believed to be an adequate candidate search.

One professor told the Harrisonburg Daily News-Record at the time, "It's one thing to do things quickly, quite another to do things intelligently."

Fifteen days later, that sentiment echoed off JMU's limestone walls loud and clear when the faculty took a vote of "no confidence" in Carrier's leadership, 24 years after "Uncle Ron" first became JMU's president. The final tally of 305-197 wasn't even close.

In a press release, Carrier defended the move as one that would make JMU "a more efficient and effective operation," and accused his faculty of trying to turn back the clock on progress.

"[The vote] represents a longing for a time where external challenges to higher education were non-existent," he said, "the demand for collaboration among departments was purely voluntary, and campus government was conducted over coffee and confined to the ivy walls."

Thirteen years later, Carrier stands by those fightin' words.

"You have to make sure the university isn't too controlled by the faculty," he says, "so it can respond through the ups and downs of the economy."

The JMU Board of Visitors insisted it had Carrier's back after the faculty vote, and the board stayed true to its word, letting him move forward with his massive restructuring. However, the faculty never did stop calling for Carrier's head. After yet another negative faculty senate vote when he unilaterally instituted a new general education curriculum on August 27, 1997, a professor remarked to the Daily News-Record, "I was a Carrier fan, but the way in which the program was being ram-rodded through the faculty was not something I could support. It's all part and parcel of a kind of university run like a 19th-century coal company rather than a university."

By March 29, 1998, Carrier decided he'd had enough and announced his resignation.

A decade later, Carrier, now chancellor at JMU, says he wouldn't change a thing about his 27 years in office, including how they ended.

"We were absolutely right," he says. "It wasn't about the faculty. I left because I had [current JMU president] Linwood Rose ready to go, I was 66, and my wife didn't want to go to any more fundraisers."

Carrier was six years further on in his tenure than Casteen is today, but Casteen has never run afoul of the faculty in the same way Carrier did– while also overseeing enormous university expansion and growth as Carrier did. How has Casteen managed to avoid the quicksand?

"The mission at UVA was clearly defined," says Carrier. "When you have to change direction as we did at JMU– when you're trying to make it into the kind of university we did– you're likely to get more controversy and encounter a whole other set of problems."

Making the ask

While the main problem Carrier faced at the start of his presidency in 1971 was the size of the university, Casteen's main problem at the start of his presidency in 1990 was the size of the university's bank account.

To that end, Casteen became one of the first of a generation of college presidents who set aside their academic backgrounds to become nearly full-time fundraisers.

By 1993, UVA's income from the Commonwealth was down to $122 million, enough to cover only 13 percent of its annual operating budget. Casteen gave up teaching one literature course per semester, and meeting regularly with his deans, in favor of being on the road four days a week fundraising.

He knew something of what could happen when the well began to dry up at a public university. As a professor at the University of California at Berkeley in the '70s, he witnessed to many a battle over funding under a cost-cutting governor named Ronald Reagan.

"It made me realize public institutions are fragile," Casteen later told a reporter, "and the need for some financial autonomy."

In that endeavor, Casteen has been wildly successful, increasing the UVA endowment to over $5 billion. But he isn't resting on those greenback laurels. The "Campaign for the University of Virginia"– launched in September 2006 with a fireworks extravaganza– at $1/74 billion and counting is well on its way to meeting its $3 billion goal. For perspective, that's an average of $2.5 million rolling into Charlottesville every day– or $103,571 every hour, $1,761 every minute.

This acumen for accumulating revenue led the New York Times to profile John Casteen as the prototype of the new college president in an August 1, 1999 piece titled "Making the Ask."

"Money's only part of what you ask for," he told the Times. "I ask for their vision of the university; I ask for their political support; I ask for their membership on committees; I ask for their children."

For making these "asks," he's well-paid. The Chronicle of Higher Education reports Casteen's annual compensation at $753,672, the highest among all public university presidents.

But it's the money he hauls in for his alma mater that may be his greatest legacy. The money has allowed UVA to construct dozens of new buildings, attract big-name professors, and create innovative scholarships for needy students.

"People don't understand what that money means," says Sabato. "No university depending solely on public money is going to be truly first rate. It's impossible. Those billions are the margin of excellence."

Casteen's leadership includes moves that can be both generous and savvy. Shortly after the kickoff of the $3 billion capital campaign, the president and his third wife, Betsy Foote Casteen, donated $500,000 to provide scholarship support for the children of UVA staff and faculty.

This was six months after Casteen had had the wage protesters squatting in his office arrested and after he had fired a faculty rabble rouser– ostensibly for using her UVA email account to send a critical message.

Not that Casteen's fundraising explosion hasn't caused some blowback for the 18-year president. As the Times reported, the constant fundraising travel did contribute to the dissolution of Casteen's marriage to his second wife, Lotta Lofgren, still a UVA English professor.

While both Lofgren and Casteen declined the Hook's requests to be interviewed for this story, Carrier affirmed to the Hook that personal strain is part and parcel of the life of a college president.

"If you don't want personal issues, you don't do it at all," he says. "If you're not willing to accept the pain, you need to get out."

John Casteen has dug deep into the pockets of UVA alumni to raise billions of dollars. In the current capital campaign alone, he raises an average of $2.5 million per day for projects like the one he broke ground for here, $37 million Bavaro Hall.

FILE PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

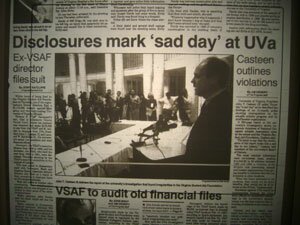

The day after Casteen held a Rotunda press conference to announce that the Virginia Student Aid Foundation had made 30 loans averaging $500 each illegal under NCAA rules, the Daily Progress spared no column inch in conveying the findings' magnitude.

HOOK PHOTO

The campaign to make former men's basketball coach Terry Holland UVA's athletic director in 1995 was a cause celebre of the same alumni who criticized Casteen for his handling of the VSAF scandal in 1992. Holland got the job and stayed at UVA for nine years.

FILE PHOTO BY LINCOLN ROSS BARBOUR

While Casteen's primary job is fundraising, UVA chief operating officer Leonard Sandridge takes care of the university's day-to-day business, such as welcoming the Rolling Stones to town in 2005

FILE PHOTO BY LINCOLN ROSS BARBOUR

Casteen (seen here with athleetic director Craig Littlepage and law school alum John Paul Jones) had a moment in the spotlight when John Paul Jones Arena opened for its first basketball game in November 2006. With a price tag of $130 million, it was one of the largest and most expensive construction projects ever undertaken by the university.

FILE PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

In 1999, the New York Times reported that the constant travel and schmoozing led to the dissolution of Casteen's marriage to his second wife, English professor Lotta Lofgren. Casteen is pictured here with third wife Betsy.

FILE PHOTO BY LINCOLN ROSS BARBOUR

#