COVER- Segregation's storytellers: History emerges from those who lived it

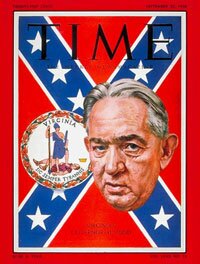

Governor Lindsay Almond's decision to close Venable Elementary and Lane High schools in Charlottesville, as well as other schools in Norfolk and Warren County, stunned the nation, and made the cover of Time's September 22, 1958, issue.

TIME MAGAZINE COVER

In 1958, if you'd said a black man would be running for president of the United States of America in 50 years– and might have a good chance at winning the job– you'd be greeted with knee-slappin' guffaws. Heck, an African American couldn't go to school with white children then, much less run for president.

And as crazy as that notion would have seemed, flip the mirror back from 2008 and chew on another seemingly insane idea: A majority of Virginia legislators would rather close the public schools than accept the enrollment of what were then called Negro children.

And that's what they did. Charlottesville, Warren County, Norfolk and Prince Edward County– the latter for five years!– were closed under the strategy called massive resistance, engineered by segregationist leader Senator Harry Byrd Sr. in defiance of the United States Supreme Court's 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

The NAACP had targeted Charlottesville for integration, and in 1955, 40 black students petitioned the Charlottesville School Board for admission to white schools. The Board ignored the petition, and the students filed suit.

By 1958, the number of plaintiffs had dwindled to 12 when on September 10 federal Judge John Paul ordered Lane High School and Venable Elementary to admit the students.

The School Board had delayed opening the schools, and fearing that schools would not open, a group of 10 mothers at Venable had already set in motion a plan to teach children should that school close. Another group, the Charlottesville Education Foundation, also made alternate plans for education: segregated private schools paid for by the state under the Tuition Reimbursement Plan. Those schools opened the following year as Robert E. Lee Elementary and Rock Hill Academy.

Sure enough, Governor Lindsay Almond ordered Venable and Lane closed, and they stayed that way for five months, until February 4, 1959.

Seventeen hundred students, the overwhelming majority of them white, had no schools to attend.

And 50 years later, citizens remember what it was like the year there was no "Back to School Night" at Venable and Lane.

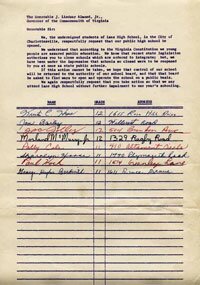

Students from Lane High petition Governor Almond to reopen their school.

LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA COLLECTION

After the 1958 school closings, the Charlottesville Education Foundation raised money to open "good private schools, operated on a racially segregated basis, [that] will contribute to the tranquility of the community..." and make "demonstrations and strife unlikely..."

LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA COLLECTION

Burley students during the massive resistance era, when the high school was the pride of the black community.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

–>

Burley students during the massive resistance era, when the high school was the pride of the black community.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

–>

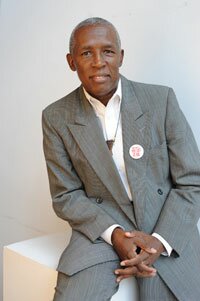

Eugene Williams

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Julia Martin

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Elizabeth Taylor

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Charles Alexander

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Charles Alexander, shown here in his seventh-grade graduation picture, says he wasn't traumatized by integrating Venable Elementary in the second grade.

PHOTO COURTESY CHARLES ALEXANDER

Mary Moon Graebner

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

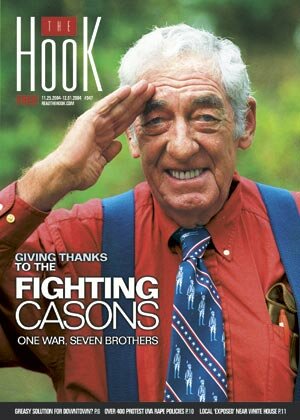

George Cason

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Paul Gaston

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Olivia Ferguson McQueen

PHOTO COURTESY OLIVIA MCQUEEN

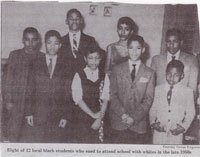

Seven of the 12 children who sued to attend white schools: Front row: either twin Roland or Ronald Woodfolk, Sandra Wicks, the other Woodfolk twin, and William Townsend. Back row: Brian Mitchell (not a plaintiff), John Martin, Olivia Ferguson, Marvin Townsend.

PHOTO COURTESY OLIVIA MCQUEEN

Pat Bailey Jensen

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Tommy Theodose

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Sherman White

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Eugene Williams

"Charlottesville was the first city in Virginia to go to court after the May 1954 Supreme Court decision," says Eugene Williams. "That's very important. It shows the leadership we had."

Williams, now 80, was among those leaders. As a top local NAACP official, he recruited plaintiffs to sue the Charlottesville School Board.

"It was a new experience for a large audience of blacks to go to U.S. District Court to see black lawyers presenting cases," says Williams, recalling some of the NAACP's storied lawyers such as Oliver Hill, Spottswood Robinson, and Samuel Tucker.

On August 10, 1958, after the School Board had appealed unsuccessfully to the U.S. Supreme Court, Judge Paul again ordered 12 black children admitted to Charlottesville schools. And on September 18, 1958, Governor Almond ordered that Lane and Venable be closed.

"I thought it was terrible," recalls Williams, although he wasn't surprised. "But I knew it wasn't going to last. We'd stay in court until it happened."

It happened on February 4, 1959, when the schools reopened– still segregated, but with integration looming for the fall of that year.

"What comes to mind, still to this day there is no real thought-out plan to desegregate," observes Williams. "That's why our schools are not measuring up academically and providing a good education for all its students."

Looking back after a lifetime fighting for civil rights, he says, "It's just so interesting the snail pace of progress, and all the roadblocks to doing the right thing."

Julia Martin

Now 85, Julia Martin admits to becoming sort of tired of talking about events of 50 years ago, but she thinks it's important to remember.

"A lot of people today think the way things are– they've always been that way," she says. "Our younger people need to know."

Martin was one of the plaintiffs suing for admission of her sons, John and Donald, into Lane High School. She worked as a domestic– one of the few career paths then available to black women– and as a taxpayer, she was rankled by the fact that her son, John, had to walk past Lane to get to Burley High, the school built for both city and Albemarle County African Americans.

"It wasn't so much for an integrated education," she says. "I paid city taxes. Why did they have to walk by one school to go to another?"

In retrospect, she says she's come to believe that the white schools weren't any better than Burley and Jefferson Elementary.

"Our schools were very good," she remarks. "I've never put down Jefferson. It was one of the best schools."

Overall, she doesn't regret sending her little boys to break the racial barriers at Lane High School, although John didn't graduate from there. He was suspended after being accused– falsely, he said– of being a gang member. "I regretted what happened to him," she says.

But the story of Charlottesville's schools being closed is part of the town's history now. "Whether you love it or hate it," she says, "it should be in there."

Elizabeth Taylor

In the spring of 1958, African-American parent Elizabeth Taylor saw a notice in the newspaper that said to sign-up rising first graders at the nearest elementary school. Living on 11th Street, she could plainly see that the nearest school for her son was just around the corner: Venable Elementary. But it was still all-white, despite Brown v. Board having struck down the concept of "separate but equal" four years earlier.

"I called up the president of the NAACP, and he said, 'Go sign him up.'"

The NAACP's Eugene Williams accompanied her to Venable May 21, 1958. "I wanted someone to be there to hear what they said," she explains.

A second parent had enrolled a child later the same day. The next day, the headline of the Richmond Times-Dispatch read, "2 Charlottesville Negroes Apply at White School."

Notice that her son, Charles Alexander, would not be admitted to Venable came by mail. And that fall, Governor Almond's order closed Venable.

"That was fine with me because he did go to classes and was tutored," says Taylor, 75. "And no, I did not feel afraid. It was a good idea because the education was not equal– the black kids were not getting the same education."

Charles Alexander

"I'm the first [African-American] student to my knowledge to enroll in a white school in Virginia," says Charles Alexander. He was six years old in 1958 when his mother, Elizabeth Taylor, signed him up to go to the school around the corner from his house, and says he was cognizant that something big was going on.

"I remember going to court in Harrisonburg," says Alexander. And he spent the first grade going to classes in the School Board administration building, along with the other 11 kids trying to attend the white schools.

"I asked my mom one time why I was part of desegregation and not my brother," recalls Alexander. "She said he didn't want to go to Venable. He was eight."

Unlike other children who met with a cold reception when they entered white schools, Alexander, now a motivational speaker known as "Alex-Zan," says he didn't have any problems.

"A lot of it," he says, "is how you present yourself to people. I've always been smiling and happy."

As for his mother's decision to break the color barrier, "She just thought it was the right thing to do," he says. "You've got a lot of people who sacrificed and made a commitment that this was going to take place. The real heroes are the parents."

Mary Moon Graebner

Long before there were soccer moms, the Venable moms mobilized an elementary school to keep classes going, even after the schoolhouse itself was shut down.

Mary Graebner, 85, was one of the 10 women who founded the Parents Committee for Emergency Schooling, whose moderate stance in the heat of tension over desegregation shifted the debate to one of public education: are you for it or against it?

"We were distressed to hear the school was going to be closed," she remembers. That summer of '58, the women met to find ad hoc classrooms– often in basements or public buildings– and teachers. The teachers were being paid while the schools were closed, and they agreed to continue teaching when the Venable moms asked.

Unlike the Charlottesville Education Foundation, formed by some of city's more prominent citizens to establish private, segregated schools like Robert E. Lee Elementary and Rock Hill Academy, the Parents Committee worked all along as a temporary fix, with the children to go back to public schools when they reopened, integrated or not.

Graebner says she was "aghast" when Governor Almond spoke out against desegregation and ordered the schools closed. She got another rude surprise when some friends stopped speaking to her.

"That hurt," she says. "It never entered my mind that children would not go to school."

George Cason

In the mid-1950s, George Cason, now 77, headed a segregationist group called the White Citizens Council.

"My main concern was that our community– Charlottesville– was getting ready to blow up if someone didn't look after things," he says from his Fluvanna County home. "There were a lot of crazy people."

He contends that his support of segregation during that period was a product of the times.

"The laws were on the books," he says. "They had been on there a long time." Furthermore, he points out, the General Assembly and the governor opposed desegregation.

"It was the time I was raised in, not the way I was raised," says Cason. "My mama and daddy never said anything about blacks."

Cason, who recalls reading a book written by a UVA professor in the 1930s touting the physical strength and intellectual inferiority of blacks, admits he was a racist. But 49 years after the first African Americans entered white schools in Charlottesville, he renounces his old ways and wishes he'd embraced desegregation sooner.

"Looking back," he says, "it should have been done 100 years earlier. And we never should have had slavery."

As for an African American running for president, Cason says of Barack Obama, "I like him a lot better than Hillary." And if Obama should win? "It wouldn't bother me. Fifty years ago, it would have."

Paul Gaston

UVA history prof emeritus Paul Gaston has been at the forefront of desegregating Charlottesville. He hosted Martin Luther King during his 1963 visit and he got beat up that same year when he tried to get an Emmet Street restaurant called Buddy's to serve African Americans.

Gaston, 80, arrived here in 1957 from Alabama, and although that might seem like an even more racist part of the country, Gaston grew up in the utopian community of Fairhope. When Governor Lindsay Almond ordered Venable and Lane closed in 1958, Gaston concedes he thought, "What in the world have I done coming to a place like this?"

He remembers a column written at that time by the Raleigh News & Observer's Jonathan Daniels, who compared Virginia's passage of Massive Resistance laws to secession from the Union during the Civil War and called it "secession from civilization."

"That was on my mind– that civilized people don't do that," says Gaston.

He still recalls an October 1958 "Save Our Schools" rally attended by 450 people at Mem Gym that was hosted by the Committee for Public Education, a group of prominent moderates, and how it was disrupted when George Cason took off his shoes, rolled up his trousers "and walked across the floor like he was stepping in you-know-what," says Gaston.

Before Almond closed the schools, Gaston had been a "great critic" of public education after attending the Waldorf-like School of Organic Education in Fairhope. But once the doors of schools were actually closed, he says, "I became a great supporter of public education, and our children went to public schools."

Olivia Ferguson McQueen

If anyone were the poster child for the sacrifices made by those young barrier-breakers who integrated schools, Olivia Ferguson McQueen might qualify. One of the 12 plaintiffs suing to attend white schools in Charlottesville, she spent her senior year away from friends and away from high school, attending class in a School Board administration building on the grounds at Venable Elementary.

"I don't think my parents gave me much of a choice," she says. "They were confident, and very supportive."

When she finished in the spring of 1959, there was no diploma and no certainty that she had the proper college credentials.

"I had a certificate that said I'd completed what was necessary for graduation from Charlottesville city schools," she says. (In 2004– the year of the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, she received an honorary diploma.)

McQueen's father was George Ferguson, a local NAACP leader, so there was no question that she would be on the forefront of desegregation. And the low-key McQueen explains why she wasn't afraid of the possibility of entering a hostile white high school.

"I think the scary part was the cross being burned on our front lawn," she says, "or when someone threw something through our front window."

At 16 that fall of 1958, she was the oldest of the plaintiffs, most of whom were elementary school kids. And she acknowledges that some might see her as a pawn in the Civil Rights movement.

"I think what would be important if I could pass it on to my grandchildren or young people is you have to make sacrifices in order to achieve whatever is the correct thing, and sacrifice is not always easy," she says.

McQueen, 66, did get into prestigious Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and went on to earn a graduate degree in early childhood education and administration. In 2000, she retired from her career in education in Washington, DC, where she still lives.

She still treasures a letter she received in 1986 from her father, who wrote: "The historic events that have taken place this January 1986– L. Douglas Wilder becoming governor of Virginia and the national holiday for Martin Luther King– came about because of the 'small crack' that you placed in the rock of segregation."

Pat Bailey Jensen

One of the bigger ironies of white Governor Lindsay Almond's decision to close Venable and Lane to keep blacks out is that it was business as usual at Jefferson Elementary and Burley High, Charlottesville's two African American schools. It was the 1,700 white kids in Charlottesville who were left school-less.

Pat Jensen was eagerly anticipating entering Lane High as an eighth grader in the fall of 1958. "In those days," she explains, "Venable was first through seventh grades. The big thing was to go to Lane. We were all looking forward to going to Lane."

After she and her classmates were sent home by the governor, hastily assembled classes met in churches and businesses. Some of her friends were sent to Scottsville or Waynesboro to attend school.

"We had one subject per day," remembers Jensen, and classes met from Monday through Saturday.

"In those days and those times," says Jensen, "we were used to coloreds and whites being separate. We were more surprised they were trying to integrate. That was the mindset in those days– not that it was right or wrong."

Her father believed strongly in segregation. "It was a big brouhaha for parents and adults," says Jensen.

She attended Lane when it reopened in February 1959, but that fall, she was enrolled at Rock Hill Academy. "It was new and exciting," she says. "For us, it was more a sense of adventure."

From the 21st-century perspective on massive resistance, Jensen has run into those who "could not believe we were not appalled, that we wouldn't fight this. Bottom line," she says, "it was certainly a racist issue."

But as an apolitical teen in the 1950s, things looked different– mostly because "this was inconvenient," she admits.

"We were all about being teenagers," says Jensen.

Tommy Theodose

He'd just started his career with Charlottesville City Schools as a history teacher at Lane in 1957. A year later, his school was closed.

"I remember teaching at churches," recalls Theodose, who went on to become head football coach in 1959 and athletic director at Charlottesville High School. "It was difficult."

The school closings opened his eyes about how unfairly African Americans were treated.

"They couldn't eat in restaurants," he says. "They couldn't go to the bathroom. They had to sit in the back of the bus."

The first black students to attend Lane weren't allowed to play football, or take part in pretty much any extracurricular activities.

"It was tough," says Theodose. "It was really, really tough for them. These were some of the top students from the black school."

Theodose recalls standing outside Lane High one day during a phys ed class with French Jackson, one of the first three African Americans to integrate Lane in 1959.

"A guy stopped and wanted to beat up me and the black kid," he says. "French Jackson said he felt very secure because he had me back him up."

Once blacks were allowed on the football team, Theodose, 75, says they were accepted by the team, but not always by the restaurants where they stopped to eat after away games. If the restaurant response was, "We'll feed you, but not the black kids, we'd say, 'We'll go somewhere else,'" says Theodose. "Mostly that was the players' decision. This is how much they accepted them."

And that's why when the team was in Richmond, "We'd go to Shoney's," adds Theodose. It was integrated.

Sherman White

"I was not a successful plaintiff," says Sherman White, one of the 12 who sued to get into the all-white schools. With the uncertainty about when or if Lane would open that September in 1958, White stayed at Jackson P. Burley High School and graduated at age 16 in 1960.

"My father was a very strong civil rights leader," says White of the man who founded the Tribune in 1954 at a time when the most of the news about the black community finding its way onto the page of the Daily Progress was when someone got shot or murdered.

"While we were going out of the house vertically every day, we could have come home horizontally," says White, 65. "That was always in the back of my mind. People were vehemently against integration."

White credits the leadership in Charlottesville, particularly Mayor Tom Michie, for maintaining peace during a difficult time.

"He let it be known then that there would be no tolerance for violence," says White. "I think that had a lot to do with it going smoothly."

Even though state-of-the art Burley High opened in 1951 to demonstrate the concept of separate but equal, White recalls it fondly– "almost like a fraternity or sorority," he says.

"It didn't matter if you were from the city or county," says White. Despite being built to "thwart" desegration, White describes the school as the "pride of black people."

Although he stayed in the warmth of the Burley community and then went on to top-ranked, historically black Howard University, White has the highest regard for his fellow plaintiffs who actually crossed the color line.

"They were pioneers," he says. "They were probably taking their lives in their hands."

And 50 years after the year Virginia closed schools, White sees integration as far from complete. "How many black people are working on the Mall?" he asks. "Who has integration really helped?

"White merchants like black dollars," he continues. "Or UVA. I love UVA. They opposed integration. Their athletic program has greatly benefited from African Americans. How have black businesses benefited? Does UVA send its uniforms to black cleaners?"

He barely pauses. "I call it modern slavery. Have things really changed?"

#