COVER- Cop out? What have police learned after last fall's crosswalk incidents?

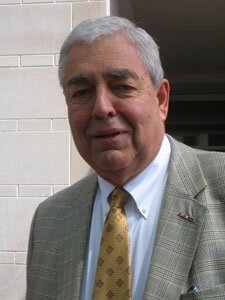

A year after the crosswalk incident, Gerry Mitchell says the effects of his injuries linger.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Last fall, in the space of six weeks, a pair of incidents between pedestrians in crosswalks and police shook Charlottesville and sparked protests and petitions demanding police accountability and greater emphasis on pedestrian rights and safety.

One year later, in the wake of those incidents, the city is spending $700,000 on pedestrian safety improvements while Police Chief Tim Longo has formed a citizen police advisory panel and boldly claims the department is a "leading advocate for pedestrian safety."

Critics, however, say these efforts are nothing more than a "band-aid" on a broken system. They blast the advisory panel as "toothless" and "meaningless," and say improved crosswalks and sidewalks are welcome– but that they don't address the police cover-up they say they witnessed last fall.

"Nothing has changed," charges Jim McKinley-Oakes, a licensed clinical social worker, who says his faith in the Charlottesville police force was shattered by what happened to his friend, Gerry Mitchell.

****

For Mitchell, the memory of November 5, 2007 is especially vivid. But should it ever dim, he'll find a reminder in a police dash cam video.

The video– which the Hook posted to YouTube after its release earlier this year– has now garnered more than 60,000 views and shows an Albemarle County police cruiser striking Mitchell's wheelchair from behind as he attempted to cross West Main Street that sunny fall morning on his way home from running errands.

If the accident itself was upsetting, it was what happened later that day that spawned true outrage. Hours after he'd been lifted out of the street by a good samaritan and by the Albemarle County officer who struck him, Mitchell– still being treated for his injuries in a UVA Medical Center emergency room– was issued a ticket by the Charlottesville police, a maneuver one lawyer blasted as a purely defensive move.

"They treated me like a dog," says Mitchell, a 54-year-old Yale-educated artist.

For weeks following the incident, Chief Longo declined comment, deferring to his officers, even as cries for an official apology rose to a roar.

But on December 12– six days after the Hook published a cover story about the incident– Longo issued a memo to City Council that cemented for many the idea that the Charlottesville Police Department would never take responsibility.

In it, Longo– who had at last watched the dash-cam video– wrote that Mitchell's chair "rolled forward several feet," and that Mitchell then "left the chair and fell to the pavement."

The memo further claimed Mitchell had appeared so suddenly that the officer hadn't had time to react– claims that would be contradicted one month later when the video was made public.

The video clearly shows the front of the cruiser as it turns left from Fourth Street onto West Main Street as Mitchell was crossing the east side of the intersection heading south. In the video, Mitchell is plainly visible even though the dash-cam captured only a narrow view directly in front of the car.

Longo claimed that the officer couldn't have seen him.

"That doesn't make sense to me unless he has zero peripheral vision," said pedestrian activist Kevin Cox at the time the video was released. "If his peripheral vision is that limited, he shouldn't be driving."

Also not mentioned in Longo's description: the audio recording of "My Humps" by the Black Eyed Peas, which kicks in immediately after impact and led some to question whether the officer had been distracted.

According to then-County police spokesman Lt. John Teixeira, that music was playing on the radio– not a department violation– and the video's audio recording kicks in only when the cruiser's lights are activated.

At a City Council meeting in mid-December, Councilors listened to pointed questions from citizens who demanded to know who had ordered the ticket for Mitchell and why no official apology had been forthcoming.

But Longo's memo, especially, prompted outrage from those who wondered how Longo could possibly claim– more than a month after the accident and after the Hook's cover story which included interviews with two men who saw the accident– that there hadn't been witnesses.

An unrepentant Longo claimed the memo was written based on the information he'd had from his officers. One year later, his defiance remains.

"I stand by that statement," Longo says in an emailed response. "Officers often have to make judgment calls based on the information they have at the moment. I was not present at the scene of this incident, and it is not my practice or appropriate for me to engage in second-guessing any of my officers through the media on any judgment call. "

The ticketing of Mitchell was not the first time police were asked to defend their actions last fall.

*****

Blair Austin will never forget the night of September 29, 2007. That was the night the young woman, celebrating her fiance's birthday– and not yet aware that she was pregnant with her first child– encountered Charlottesville Police Officer Mike Flaherty, in what would soon be seen as the opening salvo in the war of the crosswalks.

As Flaherty accelerated down Second Street past the Water Street Parking Garage, Austin and her fiance, Iraq war veteran Richard Silva, along with a group of other pedestrians, entered a crosswalk on Water Street. As the fast-moving but non-sirening cruiser turned from Second Street onto Water Street, Flaherty slammed his brakes to avoid the pedestrians, whom he nearly struck. Silva put up his hands and, according to witnesses, shouted something to the effect of "Slow your a** down."

Witnesses would later testify that Officer Flaherty appeared angry as he exited the vehicle and immediately arrested Silva. During the trial the followed, some witnesses said that when Austin approached Flaherty asking why he was arresting her fiance, Flaherty responded by shoving her to the ground.

As witness outrage mounted, a bystander called 911 to report alleged police brutality.

Flaherty's behavior seemed inexplicable to witnesses, who wondered why an officer suddenly seemed more interested in arresting a happy young couple than in responding to whatever call had prompted his rapid turn. Austin, too, was arrested and charged with obstruction of justice, a felony.

The birthday celebration ended with the future husband and wife spending the night behind bars.

At their November 27 court date in Charlottesville District Court– held just days before Silva was due to leave for six months in Afghanistan– Judge Bob Downer acquitted both Silva and Austin of all charges. But the judge stopped far short of reprimanding police or suggesting Flaherty had done anything wrong. Instead, he said, the Commonwealth simply hadn't proven its case.

The witnesses, who were strangers to the couple until the incident, said they were stunned that no one would hold the officer accountable.

"I had never seen anything like it before," said Liberty University student Anjani Solonen, who was visiting Charlottesville that night with three friends.

"It was completely ridiculous," added Carrie Stuart, visiting from California. "The officer was completely out of line."

At trial, Flaherty said that he never struck Silva, that she must have fallen when she shoved her away from his impending arrest, something he noted is part of standard police training. As for his change of focus to arresting the couple, Flaherty admitted that he chose to abort his emergency response to deal with a matter of "public safety."

Is it enough?

If the two crosswalk incidents marked D-Days, the battle hasn't ended. In July, Chief Longo unveiled his long-awaited response to those who called for additional oversight. He would create the Charlottesville Police Advisory Panel, which was finally empaneled by City Council in October. The honeymoon was brief.

"I think the police have made it clear that the panel has no oversight and virtually no authority over the police," says McKinley-Oakes. Indeed, Chief Longo has said repeatedly that the panel's mission is to improve communication between the public and police, and that it will not have investigative or disciplinary powers.

Such powers remain in the hands of Chief Longo, who to this day has not revealed how– or if– any officers were disciplined following the crosswalk incidents.

"I do not discuss personnel matters," says Longo, adding that an "internal review" examined the behavior of officers involved in both situations. "Any allegation of policy violations were investigated thoroughly and resolved in a manner consistent with our established procedure."

The public, it seems, must simply trust Longo, which McKinley-Oakes points out means there's nowhere to go if one's complaint is about the chief himself.

Last year, McKinley-Oakes wrote to City Council expressing his concerns about the police department following the Mitchell incident and asking whom he could contact to request an external investigation. Instead of hearing back from Councilors regarding the confidential complaint he thought he was making, McKinley heard from someone else: Chief Longo, to whom one or more councilors had forwarded his complaint.

"I was totally intimidated," says McKinley-Oakes, who had hoped that a police oversight committee would be more than communication or symbolism.

He's not the only person who felt intimidated by Charlottesville police.

One witness to Mitchell's accident, Ben Gathright, says he was frightened in the aftermath of the incident. At the scene, he says, he was the one who insisted that an ambulance be called. He says he asked several officers if they wanted a statement, and provided his contact information twice– yet no statement was taken.

The next day, when he learned that Mitchell, who was infected with HIV in 1981 and has fought a slew of health problems related to AIDS for nearly 20 years, had been rehospitalized, he was stunned and called the Charlottesville police again.

"I thought they should know," he says.

The response to his phone call was less than welcoming, he alleges, as an officer berated him for failing to give a statement at the scene. After the Hook's first story came out, Gathright says, he was finally called down to the Charlottesville police station to give a statement. He was given something in return– several unpaid parking tickets. And more.

That same week, a criminal charge based on an alleged bad check Gathright wrote more than a year earlier unexpectedly appeared on the Charlottesville court docket. The bounced check had cleared long before, when it was resubmitted, says Gathright, who says he has no other criminal record.

The sudden appearance of the unpaid parking tickets combined with the bad check charge left Gathright so shaken that he stopped returning phone calls from the Hook, as he wondered what else might appear from the Charlottesville PD.

Now living in Boston where he's enrolled in architecture graduate school, Gathright spoke to a reporter by telephone and says he's pleased to hear about the new police advisory board.

But Mitchell's attorney, Richard Armstrong, says the City has missed an opportunity to offer true accountability.

"For a review board to have any teeth," says Armstrong, "they have to have subpoena power, have to be able to force witnesses to come forward. If they don't, it's ultimately powerless and meaningless."

Panel member Jean Clark, a former schoolteacher who also attended the city's Citizen's Police Academy, denies such claims. "There's no need for that at this point in time," says Chase, saying it would be inappropriate for the panel to investigate.

City Councilor Julian Taliaferro– a former Charlottesville fire chief– agrees.

"I think it's going to offer the opportunity for the people on this board to voice their opinion to the chief of police, and I think he'll listen," says Taliaferro. "I don't think you can give a board of civilians the power to manage, or make disciplinary decisions."

Not everyone agrees.

"That's ridiculous," says Eduardo Diaz. The immediate past president of the National Association of Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement, or NACOLE, Diaz has been involved in police oversight since 1996 and serves on the Miami-Dade County, Florida police review board. He calls such claims "a natural defense" by law enforcement who don't want civilians meddling in departmental affairs.

"It is a fact that police work and how police do things is a learned phenomenon, and you can learn what the policies are," says Diaz. "The police work for the public, and the public needs to have an opportunity to let police know what kind of policing they want."

Railroad crackdown

So are the police giving Charlottesville the kind of policing citizens want? Some of the scores of people ticketed this summer for walking across the railroad tracks near 15th Street might think not.

"We're paying that officer," said an outraged Marya Dunlap-Brown, after she was ticketed for crossing the tracks on August 13 as she left work at UVA and headed home. Dunlap-Brown said that as Officer Stuart Bruce was writing her ticket, his radio crackled with a report of an in-progress suspected drug deal.

"Get a criminal," said Dunlap-Brown. "Catch someone selling drugs."

Or, even better, says pedestrian activist Kevin Cox, catch a driver failing to yield at a crosswalk.

A Hook Freedom of Information request found that Charlottesville Police, in one five-week span, issued 88 tickets to punish pedestrians who trespassed by stepping over railroad tracks. And yet arrest numbers suggest that Police haven't been as vigilant in protecting pedestrians.

Between January 1 and September 7, a mere 13 tickets were issued to drivers who failed to yield to pedestrians.

Such an enforcement disparity is particularly surprising to pedestrian advocate Cox, who'd been pointing out the discrepancy for months. He showed the Hook a September email from Chief Longo promising a crosswalk crackdown, but as of October 28, Longo said he was unaware of any such stakeouts at crosswalks.

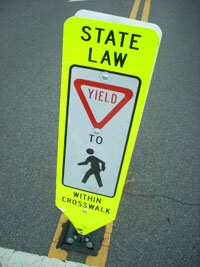

In 2006, the City planted bright yellow signs, a bold Day-Glo statement of support for pedestrians, around the downtown mall, reminding drivers of Virginia law, which requires that they yield.

"It would be nice if they'd enforce it," says Cox.

But to the chief, comparing such enforcement numbers is unfair.

"It is important for our officers to have flexibility in their patrol duties and to enforce the law if they witness citable actions," he says. "That is their responsibility."

Cox– who says he sees multiple violations of pedestrian safety on his daily five-mile foot commute– agrees with one aspect of that explanation.

"They'd witness plenty of citable actions," he says, "if they staked out crosswalks."

Moving on

The past year is a blur of health crises for Gerry Mitchell. Days after the incident, he was hospitalized with failing kidneys he blames on the impact from the cruiser. His shoulder was broken, he says, when he was lifted out of the road after being struck, permanently limiting mobility in his right arm, and a series of strokes he suffered in the hospital has caused the permanent loss of use of his right hand.

After the kidney failure, he was hospitalized with gout, which causes debilitating and agonizing joint swelling. Diabetes nearly forced doctors to amputate his right foot. Medication he took caused him to develop cataracts, and he was legally blind for several weeks until surgery restored his vision.

"People have no idea what I've gone through," says Mitchell.

Charges against him were eventually dropped in early January, after Commonwealth's Attorney Dave Chapman pointed out that the crosswalk signal at the intersection where Mitchell was hit used symbols instead of words– something Chapman said excluded it from enforcement under Virginia law.

Delegate David Toscano, a former City Councilor, rectified that situation carrying to Richmond a bill that amended the state code to ensure that any tickets issued to pedestrians can be enforced in the future.

The improvements suggested by a pedestrian safety committee (formed in the wake of the crosswalk incidents) and accepted by City Council means $700,000 will be spent improving certain corridors of the city. Already, several pedestrian crossing signs have been upgraded and now show pedestrians a countdown of seconds remaining until the light changes, helping people determine whether they have enough time to cross. Sidewalks are being repaired– to the delight of Cox, whose wife is blind– and the City is running a series of public service ads aimed at increasing driver awareness.

Last spring, Mitchell filed intent to sue against both the county and the city for their respective roles in the incident, but has not formally filed suit against either. His attorney says the County's insurance company is negotiating a settlement based on which of Mitchell's ailments can be directly tied to the accident. That settlement will likely be confidential, says Armstrong.

As for the City, Mitchell says he has decided for now to refrain from filing suit– in part because of his concern for Ben Gathright, the witness who feared further surprises.

"I realize there was no way to do that without affecting Ben," says Mitchell, "who felt he needed to pull his life back together again."

Despite his suffering, Mitchell says there have been bright moments, many of them created by the support Mitchell says he received from the community. A benefit concert in February brought about 150 of supporters to the former Prism Coffeehouse and raised approximately $2,000. To this day, Mitchell says, "people stop me on the street."

Still, painful reminders of the incident are strong, and Mitchell, who says his heart is now failing, plans to leave Charlottesville in the near future– for good. He hopes to move either to Florence, Italy, or to Santa Fe to focus on his art and on several new creative projects.

"I figure I've got about two solid years left," he says. "I feel like I need to have some joy with my work."

The other crosswalk victim says she, too, is trying to put the incident behind her.

"I've decided not to file suit," writes Austin, from her temporary home in Atlanta, where she and her now-five-month-old son are awaiting Silva's return once more– from another six-month stationing in Afghanistan. When Silva does get back, Austin says there's a good chance she'll return to Charlottesville, where Silva worked previously. She hopes not, though.

"I am not too fond of Charlottesville," she says, adding, "I'm really saddened by the impression that it has left with me."

~

Courteney Stuart is the Hook's senior editor.

#

Former Charlottesville Fire Chief and current city councilor Julian Taliaferro sits on the newly formed Charlottesville Police Advisory Panel. "I think it's going to offer the opportunity for the people on this board to voice their opinion to the chief of police," says Taliaferro, "and I think he'll listen to it."

FILE PHOTO

In 2006, Charlottesville City Council erected bold yellow signs in the middle of downtown crosswalks as a reminder to drivers that they are legally required to yield to pedestrians in crosswalks. Enforcement against errant drivers, however, hasn't measured up to CPD charges against pedestrians.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

A year after the crosswalk incidents, Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo stands by his officers. He has never revealed whether any officers faced disciplinary action for their handling of the incidents, calling such a revelation "inappropriate."

FILE PHOTO BY TOM DALY

"They treated me like a dog," says Gerry Mitchell, who filed intent to sue with both the city and the county but has not filed actual suit relating to last year's incident in a West Main Street crosswalk in which he was struck by an Albemarle police cruiser and then ticketed by Charlottesville police.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Using some of the $700,000 allotted for pedestrian improvements in certain downtown areas, City Council installed improved crosswalk signs– including a "countdown" for pedestrians– at various intersections.

PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

The dashcam video shot from the front of the Albemarle County Police Cruiser that struck Gerry Mitchell on November 5, 2007, shows Mitchell being struck, then tumbling from his chair into the road. The video also shows witness Ben Gathright and Officer Gregory C. Davis lifting Mitchell from the road and placing him back in his chair.

ALBEMARLE POLICE VIDEO

#