COVER- Horror in Mumbai: Inside a terrorist attack and the mind of Synchronicity

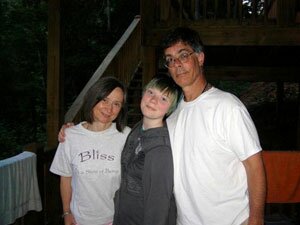

Kia Scherr and Charles Cannon, known to his Synchronicity followers as Master Charles, spoke at length to reporters during a December 2 press conference at the Foundation.

PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

"Loud gunshots."

That was the first sign of trouble for Charles Cannon, the spiritual leader of the Nelson County-based Synchronicity Foundation who had traveled to the luxurious Oberoi Hotel in downtown Mumbai, India with two dozen fellow peace-seekers. Their late November spiritual journey of meditation and enlightenment was on a collision course with an international terrorism incident that left more than 150 dead, including two of their own.

As Cannon and several followers huddled in his 12th floor hotel suite, explosions and gunshots rang out below. Downstairs, Synchronicity vice president Alan Scherr, 58, and his 13-year-old daughter, Naomi, were caught in the gunfire that erupted while they dined in the restaurant adjacent to the soaring hotel atrium.

As news of the American deaths spread, attention turned to Nelson County, where the Scherrs had lived, and to a mourning widow and mother, Kia Scherr. As she grieves in the glare of the international media spotlight, she has exhibited an uncommonly graceful demeanor. While the Scherrs' spiritual community has its critics, members of the Synchronicity Foundation say that Kia's public serenity is living proof that the group can deliver what it promises– true inner peace.

A peaceful enclave

Spiritual seekers have arrived in Nelson to discover wide skies, sweeping fields, and mountain views– as well as affordable land. Adial Road, a winding, wooded country byway just off Route 151 near Nellysford, is home to two meditation centers using sound waves to achieve higher levels of consciousness: the Monroe Institute, founded in the late 1970s by electronics guru Robert Monroe, and Synchronicity, founded by Cannon.

Cannon spent a dozen years living and studying in India with the celebrated but controversial Swami Muktananda, who Cannon says urged him to spread a postuhumous message of peace through meditation in America. In 1983, Cannon– then known as Brother Charles– purchased the first portion of what has grown to a 450-acre tract.

The Synchronicity Foundation eventually built a multi-building compound housing 15 permanent residents and welcoming guests– who pay as much as $1,500 for a week– with spiritual enlightenment from the man who is now known as Master Charles.

Two years ago, the pull to Synchronicity became even stronger for some, with the alleged appearance of the "Blessed Mother," an apparition who thrills those who claim to witness her. It was soon after his 60th birthday when Master Charles announced the Blessed Mother's presence, and skeptics have wondered if it were a ploy for money and attention. Even some of Master Charles' adherents were initially surprised. Master Charles, however, was not.

The Blessed Mother, he revealed, had been appearing to him for his entire life– something he attributed to his Catholic upbringing. But the Blessed Mother is not a Christian apparition; she is a universal divinity who can appear, Master Charles has said, "as Mother Mary of the Catholic tradition, as Kali Durga of the Hindu tradition, or as the White Buffalo Woman of the Native Americans."

While the Blessed Mother has proven such a powerful draw that Synchronicity erected a new temple just for her, the centerpiece of Synchronicity remains its use of targeted sound waves during meditation, "delivering a precision meditation experience," according to the Foundation website, which offers Alpha, Theta, and Delta-wave CDs for $15.95.

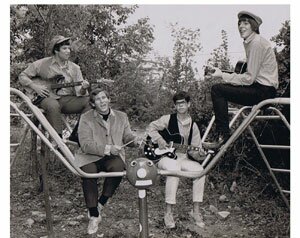

Perhaps the best known of such contemplative practices is Transcendental Meditation, a form championed by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, which won its greatest renown after the Beatles temporarily embraced it in 1967. That mingling of rock-and-roll with self-reflection was appealing to a young Alan Scherr, whose own spiritual and musical awakening was then stirring.

Alan Scherr

"Alan was a very unique guy– old beyond his years," says Russ Margo, a Baltimore musician and Sherr's bandmate in The Road Runners, a late '60s/early '70s British cover band.

"Here was a kid 15 years old singing the blues, and being able to do it," Margo recalls. "He was from a middle class Jewish family; it was not something you expect to hear."

Margo recalls an early '70s camping trip with his bandmates in which a torrential rainstorm conspired with a leaking tent and a failing air mattress to leave Scherr lying in a cold puddle.

"We were laughing, at him, at the predicament, the rain," Margo recalls. "He didn't really care for us laughing that much."

Margo says they could hear his canteen clanging against his backpack as Scherr stormed off the next morning. "We were laughing and yelling that his anger didn't reflect well on his inner serenity," says Margo. "He told us where to go."

Scherr's introspection was always leavened with bawdy humor, says Margo, who recalls countless occasions of laughing with Scherr "until we cried." The teenagers experimented with marijuana and hallucinogens, but Margo says Scherr's interest in drugs waned as his desire for more substantial enlightenment grew– along with a more serious demeanor, displayed when Scherr would attempt to discuss his awakening spirituality with bandmates, who wouldn't be coming along with him on the journey.

That camping trip, Margo says, was one of the last times he saw Scherr for a decade. But in the mid-'80s, Margo looked up his old Road Runner bandmates. Having long gotten over his campsite anger, Scherr received his old friend warmly, but the relationship had changed.

"His sense of humor, the way he would look, was more like a sense of whimsy. Kind of a chuckle, instead of a belly laugh," says Margo. "I don't think he lost his sense of humor; I think his sense of humor had changed."

There was an even simpler explanation: "He'd just outgrown us," he says.

If he'd outgrown his old bandmates, he had found new and deep kinship in a new relationship– and in another role: fatherhood.

Kia Scherr

"It started as a friendship," says Kia Scherr, recalling the early days of her relationship with Alan, when both were teaching Transcendental Meditation in Maryland in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Gradually, their friendship deepened, she says, and they eventually fell in love and married.

"He was multi-talented," says Kia, citing Alan's abilities in photography and meditation, cooking, and music. He made her laugh, she says, with an "earthy sense of humor" that he also used to help others comprehend some of the more difficult concepts in meditation.

During Naomi's infancy, the couple lived in Silver Spring, Maryland, while Alan was an art professor at the University of Maryland. But in 1996, when Naomi was two, the Scherrs decided to make a more significant commitment to Master Charles, whom both had discovered two years earlier, an experience Alan wrote about at length in an essay linked on the Synchronicity website.

"His energy seemed to move right through me, enlivening and uplifting every particle of my being," Alan wrote of an early encounter with Master Charles. "I felt a mixture of joyous ecstasy and sweet sadness welling up as tears filled my eyes. Then, looking directly at him, I thanked him for the uncountable gifts and blessings I had received since I first met him.

"'It's my intention to move here with my family and be with you,' I said. His face lit up with a broad smile. 'Just have the intention, and see what happens,' he answered."

The family moved to Faber to be close to Synchronicity, while Alan found work as a chef. About a year later, Master Charles invited the Scherrs to move to the compound. They did so, devoting themselves full time to their own meditative practice and to helping teach the Synchronicity way. Alan served as the Foundation's president and later vice president; Kia was appointed executive secretary. As Synchronicity's only resident child, Naomi was a beloved addition to the community.

"She was great," says Thomas Sechak, 30, who was already living at Synchronicity when the Scherrs moved in 11 years ago.

"When she came here, she was very quiet," Sechak recalls, and would only speak to her mother. But about six months later, he says, she opened up. "She was a chatterbox," he laughs, "asking all kinds of questions."

Sechak, who is Synchronicty's IT director in charge of website design and computer repair, says Naomi helped heal him after his own difficult early years.

"I didn't have much of a childhood. I had to be very responsible," he says. Playing with Naomi, he says, "allowed me to be a child all over again. She had that ability to bring out the fun."

As she got older, Sechak says, they remained close, and he eventually started teaching her a bit about computer repair.

"She wanted to learn computers, do graphics, and I was training her on that," he says, amused at the memory of "a 10-year-old running around helping people with their computers, installing Office Outlook, debugging software. She could do it."

It wasn't her only responsibility. Although she was young, her mother boasts that Naomi had inherited her father's gift for cooking, and more than once the girl prepared a full Zone-balanced meal for Synchronicity's residents and guests.

Life on the compound wasn't all about responsibility, says her mother, naming several of the rock bands Naomi loved: Linkin Park, My Chemical Romance, and Mindless Self-Indulgence, a name that made the teen's parents chuckle.

Sechak says he admired Kia and Alan as parents.

"They deeply cared for her, made sure she had everything she needed," he says, "and everything she wanted, within reason."

He recalls an eight-year-old Naomi wanting to dye her hair different colors. Her parents, he says, set limits. "They said, 'Once you turn this age, we'll let you put streaks in your hair.'" And they did. Last Christmas, her mother recalled at a recent press conference, Naomi's hair was purple and fuschia. By summer, it was teal, blue, and green.

"She was fascinated with all the different ways she could look," Kia said.

"She was going through a transition, being 13," agrees Sechak. "You could see that pretty quickly a new personality was emerging. It was rebellion in a postive sense, like her trying to find herself. It was fun to watch."

Turning 13 also meant another new adventure for Naomi: her first plane ride, her first trip to India.

Good news

The first few days in Mumbai were a thrill for all the members of the Synchronicity group, but perhaps none more so than Alan and Naomi Scherr.

"They were both having the time of their lives," said Kia Scherr at the December 2 press conference held in a communal gathering space at Synchronicity. Naomi was exploring Mumbai– which is both India's financial capital as well as its largest city– attending Synchronicity seminars, and enjoying one-on-one time with her father. After receiving permission from her parents, Naomi had gotten her nose pierced with a small gold stud, which she proudly showed off to Master Charles.

Several days after they'd arrived in India, Kia had called the home-schooled Naomi with good news: the eighth grader had scored a 92 percent on the SSATs, a standardized test she'd taken for entry into a prestigious boarding school in upstate New York.

"All she could say was 'Oh, my God,'" Kia recalled. When Kia spoke with Alan the next day, "We were discussing that news and what the next steps would be."

Tragically, there would be no next steps.

Under seige

Even before the battles ended, the extent of the devastation wrought by a small group of Pakistan-based terrorists began emerging. According to the most recent official reports at press time, 163 people were killed in the attacks that targeted up to 10 sites including the historic Taj Mahal hotel, a railroad station, a Jewish center, a hospital and the place where the Synchronicity pilgrims were staying: modern Oberoi Trident hotel.

A luxurious place where even the simple rooms can go for $450 a night, the 12-story Oberoi offers sunset views over the Arabian Sea.

On Wednesday, November 26, Synchronicity evening seminars ended at 8:30pm. Shortly thereafter, Alan Scherr stopped by Master Charles' top-floor suite to discuss plans for the next day. While Master Charles and several others had chosen to eat in the suite, Scherr announced to the group he'd be having dinner in Tiffin, a casual restaurant with a sushi bar located in an upper level of the hotel lobby.

Soon after, the first shots rang out.

Frantically seeking out the source of the noise, Master Charles recalled at the press conference, a friend ran to the hallway and peered over the railing to the wide-open atrium below. He returned to the room with horrific news. Gunmen were in the lobby, Master Charles recalled, "shooting everything."

The group pushed furniture against the door to barricade it, and the next 45 hours unfolded like a surreal nightmare.

"We heard very loud explosions, grenades, gunfire," said a somber Master Charles, "the volume of which you couldn't imagine."

Trapped, the group huddled, "adrenaline pumping, hearts racing, unsure what was happening." It was about to get worse.

A fire broke out on a lower level, and smoke began to filter into the suite, growing thicker to the point that visibility was obscured and breathing became increasingly difficult. For those locked in their guest rooms, there was no means of escape.

The gunmen took several hostages inside the Oberoi. Hung from one window, a makeshift banner offered a heart-breaking plea: "Save us."

Looking down to the street below, said Master Charles, a man gestured for them to break a window. The thick exterior glass made it it difficult, but the Synchronicity group turned some of the room's posh accoutrements into battering rams.

"Then," said Master Charles, "the three of us huddled, sucking air for survival."

Terror continues

By the next day, which was Thanksgiving back in America, electricity and water in the hotel went out, but cell phones remained functioning, allowing trapped travelers to receive updates from the outside and from the other members of their groups. Relief at their own survival was soon tempered by fear for their friends.

Another day dawned, and all but two members of the Synchronicity group had been accounted for. What had begun as a joyful father-daughter trip– Naomi's first chance to see the country that had long inspired her parents– ended with their lives cut brutally short.

By 3pm November 28, more than a day and a half after the horror began, Indian army commandos successfully secured the building. Explosions continued to rock the building, but this time it was security forces blowing doors off the guest rooms.

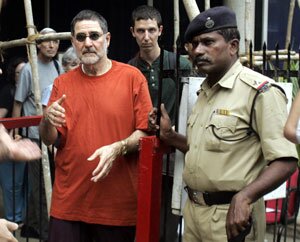

Forty-five hours after the first gunshots inside the hotel, Master Charles and his fellow Synchronicity survivors were freed, but his grimmest task lay ahead.

On their way out of the Oberoi, Master Charles said, police asked if he could identify the remains of the two people they believed to be Alan and Naomi Scherr. He agreed.

Walking through the atrium, which less than 48 hours before had been a sunlit luxury room filled with well-to-do patrons willing to spend as much as $1,400 a night for a prime seaview suite, was a horror unto itself.

"You could not believe the devastation," said Master Charles. "It was like a bombed out war zone, with blood and bodies."

Entering the restaurant, now blackened with soot, he was forced to step through pools of blood before he discovered the bodies of the fallen father and daughter.

"They were under the table," Master Charles recalled at the press conference, wiping his eyes and his voice briefly quavering, "their arms outstretched to each other and overlapping."

Only later would the details of what occurred in the restaurant be revealed.

According to various news accounts, Alan and Naomi were dining with four other Synchronicity travelers. One of them, a woman named Andreina Varagona, also known as Rüdrani Devi, told a Nashville television station that she had played dead during the attack and, as gunmen strafed the room, had been huddled under a table with a panicking Alan Scherr.

"I put my hand on the back of his neck, just saying, 'Shhh,'" she told the station. "And then I felt a bullet penetrate his head, and he just went limp, and he was bleeding all over me."

Another Synchronicity traveller, children's book author Linda Ragsdale, said she tried to save Naomi by pulling her under the table, but it was too late.

Ragsdale did not respond to the Hook's emailed request for comment by presstime, but spoke to the Washington Post about the aftermath from her bed in the Bombay Hospital, where she'd undergone surgery for a bullet wound to her back.

"I was taking in the enormity of the moment, thinking that this energetic child who I had been playing with in the pool the night before– and had made a pact to do somersaults with– was dead, shot," Ragsdale said.

Like Ragsdale, Varagona was also shot, as was a third member of their party, while a fourth escaped physically unscathed. All were eventually led to safety by hotel staff and were taken to a hospital.

For the Synchronicity survivors of the Mumbai attack, the images of the attack and the deaths of their friends will remain forever etched in their minds. Life will be forever changed. But for one woman who stayed home, life– at least as she knew it– has ended.

Peace outpouring

By December 2, five days after Kia Scherr learned her husband and daughter perished in India, she had already granted several interviews to national news media alongside Master Charles, who arrived back in Nelson County from India the night before. Just before a scheduled 2pm press conference at Synchronicity that day, soft soothing tones play over a speaker system as she arrives at the building arm in arm with one of her two adult sons from a previous marriage.

She walks slowly into the building, dressed casually in slacks, a sweater and Dansko style clogs, her brown hair, touched with gray, brushing her shoulders, her face make-up free, her brow unfurrowed. In fact, her expression, to an onlooker unaware of the terrible blow she had suffered, could seem serene.

"Kia, what's on your mind?" asks a reporter, soon after Kia has taken a seat at the front of the room, below an artist's rendition of the Blessed Mother.

"It's not what's on my mind," she quietly corrects. "It's what's in my heart."

Continuing slowly in a soft, clear, and steady voice, she recalls meeting Alan, describes their courtship, their life at Synchronicity, and, of course, their only child together, Naomi. She does not fidget. Her hands, folded mostly in her lap, remain still.

Her emotions range, she says, from "the deepest grief and pain" to gratitude for "the most love and support I've ever received."

The outpouring from across the globe, she says, has been massive– a memorial website for Alan and Naomi has collected hundreds of posts, and emails and calls expressing support have been continuous.

One might imagine an endless primal scream as the only possible response to this type of senseless violence, a lashing out at those who have terrorized for their own inexplicable reasons. But Kia Scherr seems calm. Someone watching her speak out of hearing range might imagine her discussing plans for a trip or a book she's recently read, not the recent deaths of the two people closest to her in this world.

Her external calm, she says, is thanks to her years of meditation at Synchronicity, which have trained her to remain internally balanced even in times of the most extreme external imbalance.

"Of course you are challenged to the max," she says. "But if your lifestyle is all about balance, then some balance should hold."

This particular time provides the harshest possible test of her mastery.

Master Charles later explained to reporters the tradition he teaches– that there is not good and evil, but rather "positive and negative polarities" which, he says, should balance each other out.

"My heart is broken," he says, "but at the same time the love and beauty of humanity to choose love over violence is inspiring to me."

It's a teaching Kia now truly embodies.

In the first days after Alan and Naomi's death, Kia says, she was in Florida with friends and family.

"We went outside, and the sky was black except for two bright lights," she says. Those stars, she says, represent Alan and Naomi. "Their lights will shine forever, and that's how I remember them."

Alan and Naomi are not the only ones she will think of with love. The terrorists, "shrouded and clouded by fear," are also in her thoughts.

"We must send them," she says, "our love, forgiveness, and protection."

Master Charles nods approvingly.

Naomi Scherr poses for a picture in the Oberoi Hotel in Mumbai with her new nose piercing– a long awaited wish her parents granted as part of her Indian trip.

PHOTO COURTESY SYNCHRONICITY FOUNDATION

A woman peers down through the broken window of her Oberoi Hotel window during the two-day siege.

REUTERS

"They deeply cared for her, made sure she had everything she needed and everything she wanted, within reason," says Synchronicity resident Thomas Sechak of Kia and Alan's parenting.

PHOTO COURTESY SYNCHRONICITY FOUNDATION

Master Charles is escorted from the Oberoi Hotel by Indian army commandos after the siege ended.

REUTERS

Heavily armed Indian army commandos dressed in blue camouflage patrol during the siege on the Oberoi.

REUTERS

A one-word headline sums up the two-day terrorist attack on as many as 10 targets that left more than 150 dead and dozens more injured.

REUTERS

Alan Scherr, second from right, was a teenager in the late 1960s when he played with the Baltimore-based Road Runners, a British cover band. Eventually, "he outgrew us," says his bandmate Russ Margo, far left.

PHOTO COURTESY RUSS MARGO

#