COVER- Wahoo where? What's your favorite Cavalier sports legend doing now?

Matt Blundin

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

For four years, they rise to celebrity status with Charlottesville sports fans. For that moment in time, every orange-and-blue-blooded Wahoo follows every move of these individuals in the athletic arena, and instantly recognizes them out of uniform walking around Grounds.

But then, their moment in the spotlight comes to a close with graduation. Though some go on to successful careers as professional athletes, they all eventually slip into the recesses of Cavalier memory.

Until now.

Ever wonder what happened to the quarterback who led UVA to its first ever bowl game? Or the track star who shocked the world when he won an Olympic gold medal? Or the twin sisters who intimidated Cavalier opponents and captivated a nation on the way to the Final Four? Wonder no more. We found them.

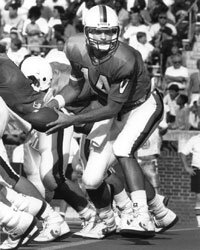

Then: Matt Blundin was a two sport star turned NFL quarterback

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

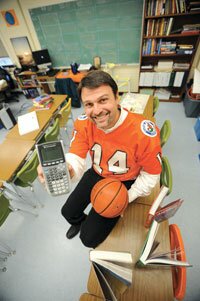

Now: "Mr. Blundin" teaches Algebra I, Algebra II, and Calculus at Western Albemarle High School.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Matt Blundin, Football/Basketball

He's the only Cavalier athlete to play in both a football bowl game and in the Elite Eight round of the NCAA basketball tournament, but Matt Blundin felt just as comfortable dissecting abstract mathematic proofs as he was dissecting opposing defenses.

"I had a great math teacher in high school," says Blundin, "and I got hooked."

So hooked was Blundin that he became a mathematics major and pulled off the rare feat of balancing x and y axes with Xs and Os in two sports. Blundin made his mark on the basketball court as a key reserve, while also marking up chalkboards in the math department, but it was on the gridiron where Blundin earned the loudest cheers.

As starting quarterback of the 1991 Cavalier football team, he threw 224 passes without a single interception, leading the 'Hoos to an 8-2-1 record and an invitation to the Gator Bowl.

NFL scouts took notice of Blundin's laser accuracy, and the Kansas City Chiefs drafted him in the second round of 1992 Draft (40th overall). But Blundin never got the chance to replicate his Cavalier glory with the Chiefs, serving only as a back-up and throwing only eight passes for a total of 15 yards in four seasons.

"It was frustrating," says Blundin, "because I saw other guys succeeding and thought I could have done as well or better than them, but in the end I was okay with it. I don't think there's anything I could have done to work harder."

So, with his football days behind him, Blundin returned to Charlottesville, to the Curry School of Education to earn his masters and become a math teacher.

"It sounds like a cliché," says Blundin, "but I was lucky enough to have people help me in academics and athletics that I wanted to do something meaningful and give back."

That is until 1997, when the Detroit Lions came calling, in need of a backup quarterback. So Blundin packed his bags and set off again for the NFL, but not before one last conversation with his advisor at the Curry School.

"I promised my professor," says Blundin, "that I'd come back and finish my degree."

It didn't take long. In Blundin's one game with the Lions, he threw one pass– an interception.

More than a decade later, Blundin has stepped away from the football field altogether, giving up coaching to focus on the classroom. "It's rewarding, and I love being a part of it," he says. Still, some of the skills honed in the huddle have come to play a role.

"As a quarterback and as a teacher," says Blundin, "you're always trying to get a big group of people to move in the same direction."

However, Blundin has not been able to leave his football career behind completely, as the Internet has allowed some students to discover their calculus teacher's previous life.

"They'll Google me and figure it out," says Blundin, "and it's neat to make a connection with a kid and have him or her ask about the NFL. But then the next day I'm just Mr. Blundin again."

Then: Heather and Heidi Burge were UVA's "Twin Towers," setting the world record for tallest female twins and anchoring the women's basketball squad that went to three consecutive Final Fours.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Seen here with their mother Mary and father Larry, Heather Quella (left) is a former Spanish teacher turned full-time mom in Los Angeles and Heidi Horton (right) is a physical therapist specializing in lower back injuries in Houston.

COURTESY OF HEATHER BURGE QUELLA

Heather Burge Quella and Heidi Burge Horton, Basketball

In 1979, UVA hit the basketball recruiting jackpot when Terry Holland convinced 7' 4" Ralph Sampson to suit up for the Cavaliers. Eleven years later, it was déja vu all over again when the eyes of the basketball nation again turned to Charlottesville when UVA landed not one, but two basketball giants.

While at UVA, sisters Heather and Heidi Burge set the world record for the world's tallest female twins at 6' 5", and together were an imposing force for any Cavalier opponent. Heather is the second leading scorer in Cavalier history; and as a duo, they averaged 24 points and seven rebounds per game, a combination that powered the 'Hoos into three consecutive Final Fours.

"I was so blessed," says Heidi, "not just to have that run, but to do it at that university where I have so many great memories, and to do it with my sister. It was unreal."

"I wouldn't trade it for anything," says Heather. "It was a fairy tale."

Such a fairy tale, in fact, that none other than the Disney Channel turned the Burges' story into the 2002 TV movie Double Teamed.

"They did a great job with that," says Heidi. "Kids in my neighborhood range from babies to age 11, and they always want to know what parts of it are true."

Their time in orange and blue proved to be the Burge sisters' basketball peak. At their athletic primes, the WNBA had yet to come into existence. In 1997, Heidi signed with the Los Angeles Sparks, and the following season, Heather joined the Sacramento Monarchs. After two injury-riddled seasons each for the sisters, both decided to pursue life after sports.

Heather put her UVA major to use teaching eighth grade Spanish near Los Angeles, and Heidi, inspired by the experience of recuperating from a career-ending back injury, became a Houston-based physical therapist specializing in lower back injuries. For both, life after basketball also meant finding tall husbands (Heather's hubby stands 6' 11", Heidi's 6' 7") and mothering tall children.

"I have a two-and-a-half year old boy, and we're expecting our second in June," says Heather. "My son is 3' 7" right now. The doctor says that he'll be around 7' 2" as an adult."

"I'm tending after a five-year-old son, and a two-year-old daughter," says Heidi. "He's already five feet tall, and she's four feet."

With height like that, might there be a chance to see Heather and Heidi's offspring on the basketball court?

"They really don't talk a whole lot about it," says Heidi. "They just think it's cool that Auntie Heather looks just like me."

However, UVA basketball coach Dave Leitao may want to make a trip out to California to see Heather's young one. Says Heather, "He's already got great follow-through on his shot."

Then: Paul Ereng was a national champion middle distance runner and shocked the world to win a gold medal in the 800m at the 1988 Summer Olympics

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: As head coach of the cross country program at the University of Texas at El Paso, Ereng is the first Kenyan to coach an American collegiate team.

COURTESY OF PAUL ERENG

Paul Ereng, Track and Field

For most of 1988, hardly anyone outside of UVA knew the name Paul Ereng. Despite the fact that he had already been a national champion running the 800m as a first-year for the Cavaliers, the 22-year-old was a relative unknown among his fellow students and Charlottesville at large.

That all changed on Monday, September 27, 1988. Running for his native Kenya at the Summer Olympics in Seoul, Ereng shocked the world when he ran from last place to first place in the men's 800m final to win the gold medal. None of the experts had picked Ereng to win, not even Ereng himself.

"I didn't expect to win that race," says Ereng. "I was overwhelmed."

So surprising was the outcome that as Ereng crossed the finish line, NBC announcer Charlie Jones bellowed the name "Nixon Kiprotich!" mistaking Ereng for his Kenyan teammate who had been running closer to the front. A full minute passed before an embarrassed Jones apologized to Ereng over the air and declared, "We just entered the world record book of blunders."

Back in Charlottesville, though, there would be no more mistaking Ereng.

"In the beginning I didn't know how to handle the attention from my classmates," says Ereng. "I just tried to tell everyone that I'm not super, I just executed something and did it well, and there's no reason to treat me differently."

After competing again in the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, and returning to finish his degree at UVA in 1993 with a major in religious studies, Ereng decided to pursue a different kind of gold.

"I went back to Kenya and started farming corn," says Ereng. "I developed a special kind of hybrid maize that was resistant to famine, which is of course common in Africa."

But finally the urge to get back into the sport he loves became too great, and in 2003 he became the head cross country coach at the University of Texas at El Paso, the first Kenyan to coach an American collegiate team. Just as in his Olympic run, the odds were against Ereng's success.

"We didn't even have running trails when I got here– just dry desert," Ereng says. "That made it tough to recruit."

Still, it took only two seasons to get UTEP back to the NCAA Championship meet for the first time in 13 years, and had a run of three consecutive conference championships starting in 2005.

Does his golden neckwear help recruit top-notch runners?

"The medal isn't magic," says Ereng, "but once they're here, it feels great to be able to share your knowledge and experience with them for their own success."

And you can be sure that when Ereng's runners cross the finish line, he calls them by their correct names.

Then: Claudio Reyna was a starting midfielder for three national champion Cavalier soccer teams.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Retired from professional soccer in 2008, Reyna has turned his attention to the cause of bringing soccer to inner-city youth.

PHOTO BY DIEGO VALENZUELA/FLICKR

Claudio Reyna, Soccer

If Claudio Reyna was wearing a UVA jersey, the Cavaliers won. That was the pattern from 1991 through 1993 when Reyna played midfield at Klöckner Stadium and the 'Hoos won back-to-back-to-back national championships.

"To be able to do it with my class all the way through," says Reyna. "That meant a lot to me, and made it difficult when it came time to leave."

But it wouldn't be goodbye for good. Reyna decided to forego his senior season to pursue a professional career in Europe, but he would be reunited with several UVA teammates when he made the U.S. national team in 1994. Eight years later, he would be playing for his former Cavalier mentor Bruce Arena when he became the head coach for Team USA in 2002.

With Reyna leading the way on the field as the team captain and Arena managing from the sideline, the Americans went on an unprecedented run in the 2002 World Cup, fighting their way to the quarterfinals of the international tournament, with Reyna earning a spot on the tournament All-Star team.

"That earned American soccer a lot of respect," says Reyna. "That's the only way the world would recognize American soccer: winning."

Of course, Reyna had already done his share to promote his country's reputation abroad. To read Reyna's resumé is to read a list of firsts: First American to captain a major European club (Germany's Wolfsburg in 1997); first American to top the $5 million mark in salary in the English Premier League (Sunderland A.F.C. paid $5.7 million for his services in 2002); first American to earn a popular nickname among English fans (fans of Manchester City F.C. dubbed Reyna "Captain America").

Now, after retiring from professional soccer last summer after two seasons playing in the MLS with Red Bull New York, Reyna is seeking to accomplish another first: giving inner-city children their first chance to play soccer as the founder and chairman of the Claudio Reyna Foundation.

"Between registration fees and equipment, soccer has gotten more and more expensive," says Reyna. "We're just trying to make sure kids from lower-income neighborhoods get the same chance to play the game as every other kid."

For Reyna, that means setting up soccer academies in Brooklyn and Newark, New Jersey offering children the chance to play the game free of charge.

"There's a demand for it," says Reyna. "A lot of them are first-generation Americans, whose parents come from countries where soccer is the #1 sport."

As for his future on the field, Reyna says he really will stay retired from playing, but expect him to walk on the field again soon in a different role.

"At 35 I accomplished more than I ever thought I would as a player," says Reyna. "But I've wanted to coach for a long time, and I'm pretty sure that will be my next challenge."

If anyone can successfully make the transition from world-class player to world-class coach, it has to be a superhero like "Captain America."

Then: John Crotty was the point guard that led UVA to the Elite Eight in 1989.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Crotty sells commercial real estate in Miami while moonlighting as a radio commentator covering the NBA's Miami Heat.

COURTESY OF JOHN CROTTY

John Crotty, Basketball

There have been bigger, taller, more athletically gifted players to wear the UVA basketball uniform over the years, but none of them can match John Crotty's skills as an on-court general. In his first season as starting point guard, second-year Crotty played beyond his years and led the Cavaliers all the way to the Elite Eight of the 1989 NCAA Tournament, defeating #1-seeded Oklahoma along the way.

Under Crotty's leadership, UVA would return to the Big Dance twice more in his junior and senior seasons, as Crotty left having engineered an overall record of 63-35 as a starting point guard.

Eighteen years after he last stepped on the court at University Hall, Crotty still holds the record for most career assists at 683. (Recent NBA draftee Sean Singletary was the last to have a shot at the record, but fell 96 assists short.)

Still, the NBA passed over Crotty when his illustrious college career ended with his 1991 graduation. But a year later, he signed as a free agent with the Utah Jazz. He ended up outlasting many of his contemporaries with an 11-year NBA career.

Now he's applying that same on-court grit to his new profession, selling commercial real estate.

"A lot of it is about determination," says Crotty, "especially in the present economic climate. You have to be able to deal with the ups and downs, and you've just got to have that mental toughness to push through the bad times."

Not to mention optimism.

"This past quarter was challenging," says Crotty, "but I'm confident we'll start seeing some movement in 2009. We've got some very good businesses here that are motivated and engaged to buy."

This, however, is only Crotty's day job. By night, he is a basketball commentator for 610 AM WIOD, the flagship radio station for the NBA's Miami Heat.

"I played most of my career in Utah," says Crotty, "but the one season I played here with the Heat, my wife and I loved the climate, and we knew that when I retired, we'd be coming back."

That retirement came following the 2002-03 season, after Crotty had just undergone his fifth knee surgery.

"That was frustrating," says Crotty, "because you work so hard at a particular skill set, but your body won't let you develop it anymore. It's weird, in most professions you get better with age, but in sports you retire when you're middle-aged."

Still, Crotty says there are worse ways to spend one's early retirement.

"I love golf, I love boating, and I love my family," says Crotty, "and here I get to enjoy all three."

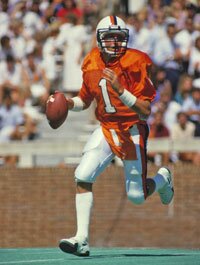

Then: As quarterback, Don Majkowski engineered UVA's first run to a bowl game in 1984.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Majkowski is an Atlanta real estate developer who spends his spare time coaching his son's football team.

COURTESY OF DON MAJKOWSKI

Don Majkowski, Football

Only one season removed from a 9-4 record and a trip to a bowl game on New Year's Day, the calls for head football coach Al Groh's head have already begun anew. For these high expectations, Groh has to thank, in some small measure, Don Majkowski.

When Majkowski first assumed the starting quarterback position in 1983, UVA had just finished its first season under new coach George Welsh with a dismal 2-8 record. But with Majkowski under center, the Cavs finished 6-5 including a big win over #19 North Carolina, Virginia's first victory over a nationally ranked opponent since 1949.

Then came Majkowski and UVA's breakout season in 1984, when the 'Hoos beat Virginia Tech, #12 West Virginia, and earned their first bid to a post-season bowl game since 1949, defeating Purdue in the Peach Bowl and finishing the season ranked #20 by the Associated Press.

"We were the pioneers, we were the nucleus of what the UVA program has become," says Majkowski, "I'm proud that we put Virginia on the map like that."

Majkowski's play wearing orange and blue also put him on the maps of NFL scouts. In 1987, the NFL's Green Bay Packers drafted Majkowski in the 10th round. Rarely do players drafted that late make it into a starting role, but in his rookie year, Majkowski won the starting job to begin the season, and had the best record of the Packers' three starting QBs that season at 2-2-1.

After splitting starting duties again in 1988, there would be no doubting Majkowski's status as Green Bay's top dog in 1989, when he led the Packers to a 10-6 record, earned a trip to the Pro Bowl, and got the nickname "Majik Man."

But ultimately, Majkowski's career would effectively be cut short in one play. On September 20, 1992, Majkowski went down in the first quarter of a game against the Cincinnati Bengals with torn ligaments in his left ankle.

With Majkowski unable to play, in walked Majkowski's backup: Brett Favre.

Favre threw the game-winning touchdown with 19 seconds to go in the fourth quarter, for a 24-23 victory. Favre started the next game, and Majkowski never got his job back, as that game was the first in a still unbroken streak of 269 consecutive starts for Favre.

After so-so stints with the Indianapolis Colts and Detroit Lions, Majkowski hung up his cleats in 1996.

"It was tough to deal with, but it's part of the game," says Majkowski. "If someone's going to take your place, it may as well be someone who's gone on to have a career as great as Brett Favre."

While Majkowski says he's still good friends with Favre, and that he's dealt with the emotional pain of losing the job, the physical pain remains.

"I just had my eleventh surgery on that ankle in the last three years," says Majkowski. "They put some titanium plates in there where the cartilage was. Hopefully, that's the last of it."

These days Majkowski makes his home in Atlanta as a real estate developer.

"I buy up foreclosed properties," says Majkowski. "With the market doing what it's doing right now, I've bought up a lot of lower income housing in Atlanta and am renting them right now. I've already sold a few of them, though. Things are starting to pick up."

When he's not busy making the sale, he's spending his spare time making the next great quarterback, coaching the Alpharetta Eagles in Atlanta's North Metro Football League.

"I'm coaching my son's team. Make a note now– remember the name Bo Cannon Majkowski," says the proud papa. "He's only 10, but he's already got a great arm and great vision for the field. He's going to be phenomenal."

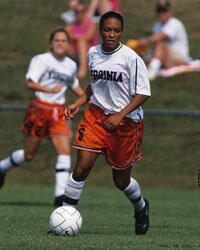

Then: Angela Hucles set the all-time goals record as a forward for UVA's women's soccer team.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Hucles has won gold medals in two different Olympics. She scored four goals in Bejing, including the game-winning goal that put Team USA into the 2008 gold medal game.

COURTESY OF ANGELA HUCLES

Angela Hucles, Soccer

For her four seasons as a Cavalier, Angela Hucles simply was UVA women's soccer.

She earned All-ACC honors all four years, twice tapped as an All-American (the first Cavalier to earn the honor), and left UVA in 2000 as the 'Hoos' all time leader in goals (59).

But even this could not have foretold Hucles' success on a bigger stage.

Though she won a gold medal as a reserve on the victorious 2004 U.S. women's soccer team in Athens, Hucles' star did not truly shine until last year's Summer Olympics in Beijing.

Following a disappointing 2-0 loss against Norway to open group play, Hucles caught fire, scoring a goal against New Zealand in group play, another against Canada in the quarterfinals, and two to dispatch Japan in the 4-2 win that put Team USA into the gold medal match. Hucles' four goals were the most of anyone on the team, and after a 1-0 win over Brazil in the finals, Hucles was an Olympic champion again.

"The irony is I didn't even think I was going to play forward, let alone score those goals," says Hucles. "I got lucky, really. My teammates set me up well, and I just made the best of those opportunities."

Now that the whirlwind tour of the country following the Olympics has ended, Hucles' is settling back into her day-to-day life as a player for the Boston Breakers. Hucles had played for the Breakers from 2001 to 2003, but then the Women's United Soccer Association folded following the 2003 season. Now, the Breakers have been revived as part of the new Women's Professional Soccer league, and she's preparing for the coming season in the spring.

"I'm glad to be back playing professionally again," says Hucles. "We're really lucky that the league is already doing well enough that we're paid full-time, and I get to concentrate on soccer."

Still, any hardware Hucles could win on the professional field would have a hard time beating Olympic gold.

"Some people keep them in safes, but I like to go to schools with the medal, I love sharing it with people," says Hucles. "People certainly do look at you differently with a gold medal around your neck."

Then: Third baseman for a UVA baseball program on the rise.

COURTESY OF UVA ATHLETICS

Now: Third baseman playing for the Washington Nationals

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Ryan Zimmerman, Baseball

When Ryan Zimmerman arrived on Grounds to play baseball for UVA, nobody would have guessed he would be headed to the Major Leagues, not even Zimmerman himself.

"I really had no clue," says Zimmerman. "I could field okay, but I hadn't really grown into my body yet. I was still pretty goofy at the plate."

What a difference four years and a little weight training can make. By the time Zimmerman left UVA, he had a career batting average of .355 (fourth-best in school history) with 140 RBIs (eighth-best all-time), leading the Cavaliers to two NCAA Tournament appearances, and earning All-American honors in 2004 and 2005. By the time of the Major League Amateur Draft, the Washington Nationals had taken notice and drafted him fourth overall, the highest a Cavalier had ever been selected.

A mere three months later, he had worked his way out of the minors onto the Major League on September 1, 2005.

"The first time you step up to the plate," says Zimmerman, "the adrenaline that rushes through you is unlike anything I'd felt up to that point in my life."

While that first at-bat resulted in a strikeout, it didn't take long for Zimmerman to become one of the game's premiere up-and-comers. In 2006, the rookie was the Nationals' starting third-baseman, ending the season with a .287 batting average, 20 home runs, and 110 RBI, and lost the National League Rookie of the Year Award by a mere four votes.

Still, none of Zimmerman's veteran-level success could tamper his sense of wonder as a rookie.

"I remember the first time I batted against [Atlanta Braves pitcher] John Smoltz," says Zimmerman. "Having grown up a Braves fan and watching him on TV, going up against him was a thrill."

As the former Cav continues to wow fans, there's no telling which wide-eyed rookie could be saying the same of Zimmerman in 10 years.

#