COVER- King of the Road: The unstoppable Wendell Wood

"People who oppose this stuff all have jobs," says Wood of those who would try to stop or thwart development. "They drive Volvos and Mercedes, and live pretty comfortably. This is where it all falls apart for me. What I do creates opportunities for people. And if you simply plan properly, you can deal with growth."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

A few weeks ago, we contacted developer Wendell Wood to ask if he would respond to rumors that he was building a palatial mansion in Southern Albemarle County. When he called back, he didn't want to talk about his house, though he neither confirmed nor denied the rumors. He just changed the subject.

"Why would you want to write about some house I'm building?" he said. "The real story is the expansion around NGIC and how it's going to bring 1,500 new jobs to the area. Now that's a story."

Wood offered instead to show us his new 122,000-square-foot high-security office building adjacent to NGIC, the National Ground Intelligence Center, on Route 29, which he plans to lease to the federal government when the new structure is completed in March. As is often the case with big developments, getting approval on the project was not easy.

As is also often the case, Wood got his way.

For four decades the developer has been buying up land and, as he puts it, "making things happen" along 29 North in a kind of real estate chess match that has become his life's work. Wood uses a simpler analogy, comparing land buying to eating a pie.

"You take one piece, then you come back and take another, then another," he says, "but it's that last piece of pie that is the most valuable."

But he's clearly oversimplifying; he has had a hand in developing nearly everything familiar along 29 North, from the the Barracks Road Shopping Center to Fashion Square Mall, Wal-Mart to the Hollymead Town Center, and the NGIC, to name just a few. And it has made him rich. In 2001, Virginia Business Magazine listed him as one of the 50 wealthiest people in Virginia with a net worth of $160 million.

If these developments sometimes seem to materialize in the matter of a year or two, Wood says that's simply not the case.

"What people don't realize," he says, "Is that none of this happened overnight."

For example, the current NGIC expansion, one of Wood's most recent chess moves, was set in motion almost 30 years ago when he began slowly amassing a 1,000-acre tract of land just north of the airport, waiting for the right deal. Wood also points out that he bought 40 individual properties over 25 years to piece together another tract that would become home to the Hollymead Town Center.

In the late 1990s, Wood says he entered into an agreement with Value America founder Craig Winn, who planned to build the then rising dot-com's corporate headquarters on the current NGIC site. Wood chuckles remembering that failed deal, admitting that he bought shares in Value America, which became worthless less than a year after the company went public. Undeterred, Wood eventually ended up selling 30 acres to the U.S. Army for $1 million, as the NGIC moved from its old location downtown in the current SNL building to the new location on 29 North in 2001.

In Wood's chess game, that was check.

In 2005, the Department of Defense, under federal Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) legislation, ordered the closure and relocation of military facilities across the country, with an emphasis on grouping various operations in a single location. As a result, the Army came to Wood looking for land for a new $58 million, 165,000-square-foot Joint Use Intelligence Analysis Facility for the Defense Intelligence Agency, which would also house personnel from the crowded NGIC facility.

According to military documents available online, the plan is to create one big military installation for both intelligence operations, called the Rivanna Station Military Base, which could include additional warehouses, a multi-level parking garage, and an addition to the NGIC facility. As evidence of future expansion, the documents show that the Army was proposing to purchase 100 acres of land adjacent to Rivanna Station "to prevent future encroachment around the Station by private development."

Indeed, Wood says, he initially agreed to sell the Army 96 more acres for $18 million, but soon after that agreement, the Army informed him that it had only been allocated $7 million for the land purchase. Could they buy 46.7 acres for that amount?

Wood was reluctant to part with the land at that price, which he contended was worth much more, so he asked Albemarle County if it would consider re-zoning 30 agriculturally zoned acres nearby for development if he agreed to sell the Army the land for $7 million.

Moving the growth area boundaries is a rare event, typically undertaken only with a long and public process, but as Wood pointed out, the Army was receiving plenty of attractive offers elsewhere, and was under a strict deadline to relocate personnel. If the County didn't act fast, Wood claimed, the Army might go elsewhere.

Wood argued that he was willing to take a financial hit on the sale to ensure that the Army continued to expand in the Charlottesville area. But he wanted the County to "share the pain" and allow him recoup his losses.

Faced with the possibility of losing a major employer, the County Supervisors took heed. Wood says Army officials met privately with the Supes, two-by-two, to avoid having to hold public hearings, and assured them that Wood was telling the truth.

The land they wanted had been appraised for more than they were paying they said– although they wouldn't reveal how much– and there was a risk of relocation if they weren't guaranteed room to expand. The County Supes finally voted 5-1 in May 2006 to give Wood what he wanted.

Checkmate. And proof that that last piece of pie is worth the most.

Indeed, even though Wood technically took a hit on his $7 million land sale to the Army, it was still seven times more than the previous piece of pie he sold them. Not everyone was happy with Wood's latest success.

A year later, former C-Ville Weekly reporter Jayson Whitehead published a story that detailed the inner workings of the land deal, and Wood came under heavy criticism from folks who felt he had coerced the County into re-zoning previously protected land, which he stood to make millions developing.

In particular, one story noted that Supervisor Sally Thomas, the lone nay vote, had accused Wood of "holding up" the County by refusing to take the Army's offer and asking for the re-zoning. She also questioned whether or not Wood and the Army were being truthful about the value of the land, since the Army had refused to reveal the value in its appraisal.

Around the time of the County vote, Wood told growth watchdog group Charlottesville Tomorrow, which has covered the NGIC land deal in great detail, the government was offering $4.5 million less than the property's appraised value.

Radio talk show host Coy Barefoot began decrying the secrecy of the deal, and eventually, journalist Whitehead filed a FOIA request for the appraisal, which resulted in a lawsuit after the Army again refused to reveal the amount.

Whitehead prevailed. The Army appraisal came in at $9.7 million. Not quite the $4.5 million more that Wood said it was worth in 2006, but it was more.

For his part, Wood claims to be baffled by the controversy, which he says seemed to "take on a life of its own." County supervisor Ken Boyd called it a "tempest in a teapot" and told the Hook in 2007, during his re-election run, that he thought the C-Ville story had "made a mountain out of a molehill."

In a follow-up piece, after Whitehead had left the paper, C-Ville reporter Will Goldsmith seemed to downplay the successful lawsuit, saying Whitehead had come "out on top– sort of."

But Whitehead believes the lawsuit was important, as it took the Army to task for refusing to reveal information that, as Thomas believed, was central to making an informed decision about a land deal.

"I don't think the military will change how it does things because of my FOIA suit at all," says Whitehead, " but perhaps they will be a tad more open with the supervisors the next time something like this happens. I still don't see why the Supes had to be in the dark concerning the appraisal amount."

In addition, Whitehead says the amount Wood claimed he was loosing on the sale was important as to bargaining position.

"Wood cast himself as a victim, someone who was taking a massive hit, as a result he was refusing to sell unless the county gave him concessions," says Whitehead. "To me that only makes sense if the land was indeed worth what he said it was. However, if it's only worth around $9 million then it seems like a calculated loss perhaps worth taking, because the military is going to continue to expand and Wood will continue to benefit as we see with the building he's about to open nearby.

"I think the question you have to ask is whether in light of the difference he was going to receive versus the Army's assessment, was it permissible to let Wood skirt the process whereby land would change designation from rural to growth, the same process you or I would have to labor through for years?"

Indeed, Wood says the 30 acres in question will undoubtedly be developed to accommodate further government expansion on the site, but he doesn't see what all the fuss is about fast-tracking the process. And he insists he had no idea what the Army had appraised the land for. His own appraisal of the land's value, he says, was based on what he believed it was worth.

"It was a reality that NGIC was going to expand, and that there was a risk that they might relocate if they couldn't. That was just a fact," said Wood. "I wanted the re-zoning to allow them to grow, to keep them here, not just to recoup my loss."

When he later proposed developing five commercial buildings in support of the Army's expansion, Wood also encountered resistance from the County Supes who wanted proof he was actually going to lease those properties to the government.

"I didn't have any proof," says Wood, "so they said Wendell Wood was bullsh*tting."

After the Supes eventually gave Wood what he wanted, Charlottesville Tomorrow executive director Brian Wheeler made a public statement immediately after the vote.

"My organization does not have a position on this rezoning or the expansion of NGIC," Wheeler began, before accusing the Supes of giving Wood "special treatment" and conducting business "behind closed doors."

Now that the building is almost finished, it appears to prove that Wood was not bullsh*tting. Built to specifications in an anti-terrorism building manual two-inches thick, which the federal government requires, the five-story building is a veritable fortress.

While Wood asks that what makes it that way not be described in print, lest he breech some security protocol by giving a journalist a tour, rest assured that this is like no other local office building.

Unprompted, Wood brings up the subject of his house again as he's showing a reporter around, saying, "I don't understand why you would want to write about some house I'm building, when you could write about this!"

Indeed, if terrorists decided to attack Charlottesville, the building would likely be the only thing standing, along with the advanced technology for which it's wired. Wood says the building itself will cost $40 million, while its specialized components will add an additional $60 million.

Given the critical reception he receives in the media, one might expect Wood to be a gruff, intimidating man, intent on demanding that a story spin a certain way. While he was certainly opinionated and hoped this story would be about jobs, he turns out to be remarkably unassuming for a guy building a $100 million building.

"Here, look at this... isn't this something?" he says with boyish enthusiasm as we enter another room in the fortress, as if all he wants is for someone to appreciate what he's doing for once.

Though almost 70, Wood races up the stairway as we visit each floor while a winded reporter follows. His son, Hunter, is heading the construction crew, indistinguishable from the other workers in hard hats who are all threading massive electrical cables through steel tubes. Everyone knows Wood by sight– including the security guard– and some of the workers make sure to get a little facetime with the boss to ask about any other projects he has coming online.

As we look out the fifth story window of the building, it appears that Wood's plan for the property is falling into place. Ground has broken on the new Joint Use Intelligence Analysis Facility beside the current NGIC building. The new facility will accommodate 1,000 additional Army employees, and Wood has plans in the works for five more buildings to accommodate any future expansion. And to the east, just beyond a ridge below which Wood has built a small lake, where a single white gazebo stands on a rise, lies another 1,000 acres of rolling hills and pasture land he owns, 200 acres of which are in the growth area, just waiting for the right deal.

"If we're going to have growth," he says. "This is where it should happen."

Indeed, as critics of Wood's developments and land deals have learned repeatedly, the developer's slow-cooked plans are like a force of nature.

"[Wood]'s been correct more than us," admits Rich Collins, a long-time anti-sprawl advocate who helped found the area's most prominent anti-growth group, ASAP, Advocates for a Sustainable Population.

"I remember in 1978, he and developer Charlie Hurt were saying that Route 29, when there was nothing there, was going to be the new Main Street," says Collins. "And he was right."

Indeed, all the County Supes, save for Thomas, appear to have thought Wood was right again on the NGIC deal, however much they may have disliked his methods.

As for Thomas, Wood appears to harbor a particular frustration; he thinks she never wanted the Army here in the first place. "Everyone else was rolling out the red carpet for them," says Wood, "and here we were fighting over it."

"But can't you understand where folks like Collins and Thomas are coming from?" a reporter asks. "That they simply want to promote responsible growth?"

"I try to understand them," says Wood, "but when I look at the consequences, the other side, I can't understand."

For Wood, Thomas and Collins may speak for a certain class of people who don't understand how the real world works.

"People who oppose this stuff all have jobs," says Wood. "They drive Volvos and Mercedes, and live pretty comfortably. This is where it all falls apart for me. What I do creates opportunities for people. And if you simply plan properly, you can deal with growth."

"I may understand developers' pride in what they do, better than developers would expect me to," says Thomas. My grandfather was a major land developer in a midwestern state. Seeing families happy in new homes is something a developer has every right to feel proud about."

That said, however, Thomas makes it clear where she stands.

"Those families, newcomers and old-timers, also have dreams and expectations," she says, "dreams of good schools, good public safety services, of responsibly dealing with the environment, and those dreams for their community seldom include having green fields turned into suburbs."

Like many growth critics, Thomas counters Wood's job creation argument by pointing out that population growth increases the tax burden of existing residents.

"So, when developers want to stimulate population growth so they can make more money, sell more houses, etcetera, "she says, "that can run into conflict with a local government responding to residents' desires to have only slow growth, strong environmental protection, uncrowded schools, and low taxes."

Still, Thomas claims it's nothing personal.

"The conflict between local politicians and developers is not a matter of personalities, but of motivations," she says, "which is pretty natural and understandable to me."

Like an experienced general, Collins, too, seems to have a certain understanding of the other side.

"He speaks his mind," says Collins, "and he is earthy and confident in his prescriptions."

But Collins is clear about what he thinks is at stake: that Charlottesville will become part of the East Coast's megalopolis, that ever expanding chain of development stretching from southern Maine to Florida.

"Developers always say this kind of sprawl is inevitable and good, and we say it's not," says Collins. "This is what the growth/no growth argument is all about."

Collins and Thomas may be fond of Wood despite their disagreements; others, however, aren't quite as charmed by his rhetoric.

"I see Mr. Wood has resurrected a well-worn cliché," says local preservation activist Aaron Wunsch, "the large-spirited, pro-business opportunity-generator versus the latte-sipping liberal elitist."

Wunsch, an anti-sprawler and high density advocate, recently blamed Wood for ruining our quality of life in a recent Daily Progress letter.

"Thanks to Mr. Wood and his United Land Company, Charlottesville has grown out rather than up. A drive from downtown to the airport now takes approximately twice as long as it did in the 1990s because of the seemingly endless sprawl Mr. Wood has helped generate on U.S. 29."

Wunsch was responding to a previously published letter by retired business owner Bobby McCauley, who termed Wood "honest" and "reliable," a "hardworking citizen who creates jobs, pays taxes, and helps our community grow and prosper." McCauley said it bothered him to read so many negative articles about Wood.

Indeed, despite Wood's successes and contributions, which include landing a Target store at his Hollymead Town Center development, he seems always to be a target.

In February 2005, in an attack described as "eco-terrorism," Wood lost two trucks and a trackhoe to arson on the construction site– an attack accompanied by a banner boasting, "Your construction = long-term destruction– E[arth] L[iberation] F[ront]."

No one was ever prosecuted in the destruction.

"Mr. Wood would have us believe everything is black and white, but that's a false choice," says Wunsch. "The choice isn't between jobs or no jobs. It's between short-term profits and long-term benefits."

Wunsch would rather see the kind of vertical, condensed growth that has brought us the nine-story Landmark Hotel, the proposed Water House development, and the planned development for the Ix buildings.

"I'm willing to wager there are more jobs created by one of these projects than in a mile of Mr. Wood's sprawl," says Wunsch. "Better yet, these jobs have been created without the ugly side effects of destroying the countryside and creating huge traffic jams."

Of course, developments are only as good as the developers behind them. Wunsch may have a point, but what good are those projects if they take years to build or never get built at all? As recently reported, the development team behind the Landmark hotel had a falling out and/or financial problems, which resulted in public name-calling and construction delays. Meanwhile, the list of nine-story condo towers planned for downtown dwarfs the list of those actually getting built.

Wunsch points out that people move to this area precisely because it is not like Paramus– a mid-sized Borough of approximately 26,000 residents in northeast New Jersey– which he says was destroyed by sprawl.

"They move here because the air and water are clean, the views are spectacular, the schools are good, and the economy is relatively good," he says. "In Paramus, perhaps under the cloak of job creation, guys like Wood were given free reign. Parts of Paramus are still in business, but much of it is dead, engulfed by empty big box stores and vast seas of parking. Is this the utopia Mr. Wood envisions? Is this the future we want?"

It's certainly not the future that Collins wants, and he's not about to give up the fight against unchecked growth, despite admitting that his losses to developers like Wood have made his mission feel quixotic. He argued against the creation of Fashion Square Mall, claiming it would crush downtown, and helped found the group STAMP, Sensible Transportation Alternatives to the Meadowcreek Parkway.

"Just by delaying things, we can get things done," says Collins, who says opposition to the Meadowcreek project has led to concessions, such as changing it from four lanes to two, banning trucks, and various modifications to its design and scope. "There's no reason this has to be just another old-fashioned road."

While Collins believes it's important to promote the values of scale that developments are founded on, and is willing to stall the process, Wood says it's more important to get things done.

"[The Parkway] needs to be done, and we've been talking about it for 25 years," says Wood, who has land along the planned Parkway route poised for development. "We've spent more money studying it than it would have cost to build it back then. When you stop something, it hurts good planning."

Of course, what Wood's legacy has really meant for Charlottesville depends on what you see when you drive along 29 North, or what tribe involved in the growth debate you belong to. For people who see commercial routes like 29 North as the ugly endgame of human evolution, snarling roads with traffic, destroying the environment, and filling landscapes with horrible architecture, well then, Wood has a patch over one eye, a peg leg, and he laughs lustily as he shows us his treasure map.

But for those who see these same commercial routes as as economic engines generating income and offering the masses treasures and comforts once only available to kings and pharaohs— what once required 50 slaves with fans, anyone can have by buying a $125 air conditioner at Lowes–- Wood wears shining armor, rides a gleaming backhoe, and delivers us a Target, jobs, and a large, reliable employer in a time of economic hardship.

As we say good-bye, Wood again says he hopes the story will be about the jobs created by the NGIC expansion, and "not about me and some house I'm building." I imply that it's unlikely that the story won't be about him and that his house won't get mentioned, which he seems resigned to.

"It's just that people hate me enough as it is," he says with a smile.

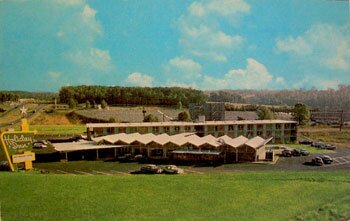

Then and now: A post card from the 1960s shows the old Holiday Inn at the intersection of Emmet Street and the 250 by-pass, with the old Ridge Drive-In and a dense forrest behind it. Today, it's a Days Inn and a Red Lobster restaurant, with with gas stations, office buildings, a Kroger, and a K-Mart behind it.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR/POST CARD COURTESY CHARLOTTESVILLE ALBEMARLE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

This high-security, 122,000 square foot office building, one of five commercial buildings that Wood plans to build on spec, is being leased to the Federal government in March. Because it had to meet special Federal anti-terrorism specifications, and will have high-tech gizmos, it will cost an estimated $100 million to build.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

Wood compares land buying to eating a pie. "You take one piece, then you come back and take another, then another," he says, "but it's that last piece of pie that is the most valuable."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Beyond a ridge adjacent the the NGIC complex Wood owns a 1000 acres of undeveloped rolling hills and pastures, 200 acres of which is in the growth area, just waiting for the right deal.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

" [Wood]'s been correct more than us," admits Rich Collins, a long-time anti-sprawl advocate who helped found the area's most prominent anti-growth group, ASAP, Advocates for a Sustainable Population. "I remember in 1978 he and developer Charlie Hurt were saying that Route 29, when there was nothing there, was going to be the new Main Street. And he was right."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"Seeing families happy in new homes is something a developer has every right to feel proud about," says County Supervisor Sally Thomas, "but those families, newcomers and old-timers, also have dreams and expectations, dreams of good schools, good public safety services, of responsibly dealing with the environment, and those dreams for their community seldom include having green fields turned into suburbs."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#