COVER- Surviving the Depression: True tales of the 1930s

The economy has crashed and millions of Americans have lost jobs, lost their homes, aren't sure where their next meal is coming from and basically are in Despair Central. It may seem to the softest generations– Baby Boomers and younger– things are about as bad as we've seen.

But hard times are nothing new.

Those who lived through the Great Depression remember an irrationally exuberant stock market that came crashing down and the grim aftermath. They weren't mortgaged to the hilt. They didn't have credit cards. They weren't aflood in consumer goods they believed they were entitled to have, even if their bank accounts didn't support the acquisition. Then they fought overseas or sustained the home front in World War II. Tom Brokaw calls them Greatest Generation.

These 80- and 90-somethings haven't forgotten the past, although they do appear destined to live through two depressions in one lifetime.

They already know that life is unfair, and they're certainly better poised to endure the ongoing pain than many of us are. What can we learn from those who lived through the toughest times of the past century?

Bill Black, above on the left with his brothers in 1925, graduated high school in 1934 in Mt. Vernon, Ohio, right, and made 40 cents an hour working in the coal yard.

PHOTO COURTESY BILL BLACK

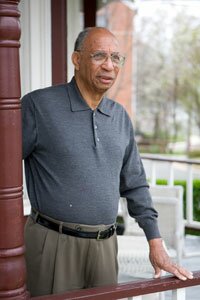

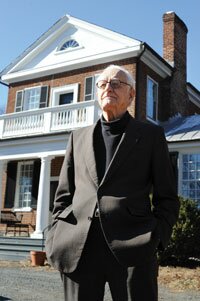

Don't get into too much debt, advises Bill Black, photographed at Lewis and Clark Square.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

At least Prohibition ended

William Black

Born 1916

Grew up in Mount Vernon, Ohio

President Barack Obama's plans to invest in infrastructure remind William Black of the WPA– the Works Progress Administration, later renamed the Work Projects Administration– that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt implemented to get the unemployed back to work.

When Black was 12, he had a paper route carrying the Columbus Dispatch. The daily paper cost 2 cents and the Sunday paper 10 cents.

"I carried some of my customers who couldn't afford 22 cents a week," says Black.

He also worked at a coal yard, where "relief coal" was common. A ton of coal cost $4.50 to $5, he explains. "People couldn't afford that." They brought a gunnysack to the coal yard and could fill that for 50 cents.

"Relief coal came from government money," says Black. "You'd get a certificate for a ton of coal. Sixty percent of our business was relief coal."

Black also worked at a shoe store in high school, where shoes for the common man cost $1.95 and $2.95. "The $1.95 shoes didn't last too long," he says.

And from Richman Brothers Clothes out of Cleveland, a suit came with a jacket, vest, two pairs of trousers and the slogan, "Make you look nifty for $22.50."

"I had to work," says Black. "My father was a chiropractor. He charged $1 per adjustment." To lure in business, his father offered a discount card that was punched each visit, so that his patients could get six adjustments for $5.

Black's grandfather owned a restaurant in Mount Vernon. "They had discount cards, too," says Black, displaying an uncanny recall of prices. A meal of meat, potatoes, a vegetable, and bread and butter could be had for 35 cents. A piece of pie cost 10 cents, and a cup of coffee was a nickel.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, his grandfather's place was the first in town to serve beer. "Men would line up around the corner, come in, sit and have two beers," says Black. If they wanted more than two beers, "then he'd make them line up again."

When the taps started flowing again after the long, dry years of Prohibition, beer was only available in kegs– there were no bottles. "We had a hard time figuring out how to keep the kegs from blowing up," notes Black.

Here are some other things Black, 92, remembers from that era:

- Spring cleaning. With all that coal, walls had to be cleaned because houses were filthy, and there was a special cleaner to remove soot from wallpaper.

- The Ku Klux Klan was active in the middle of Ohio. "I saw them burn a cross," says Black.

- Gathering chestnuts. "They were wonderful roasted," Black recalls. That was before a blight made chestnut trees virtually extinct in America.

- Gathering mushrooms. The good places were kept secret, "like good fishing holes."

- Minstrel shows. Actors sat in a semi-circle, and the ones on the end were in black face.

- Electric cars, typically driven by elderly women, according to Black. "There was no steering wheel. It used a tiller and it was totally silent. It was charged every night in garages."

- Cars no longer around: Willis Knight, Graham Paige, Hudson Terraplane, Studebaker, LaSalle, Packard, Stanley Steamer, Du Pont, Nash, Pierce Arrow, Franklin.

Black was in the printing business for 45 years and did very well at it. "Printing was my life," he says. "It wasn't my first choice, but it was all I knew."

His second marriage to Anne McIntire from Keswick brought him to this area. One daughter, Cindy McClelland, runs downtown women's boutique Eloise, and daughter Pamela Black teaches art at UVA.

"I feel we need more positive releases from the media," opines Black about the current economic situation. "Headlines are how bad things are. That's not the right thing."

And the Great Depression's most lasting affect on him? Says Black, "I was wildly interested in not being poor."

Nancy Barnett's parents: Blanche and Morton Whiting had 10 children and supported them on the $2.50 a day he made working at Mirador.

PHOTO COURTESY NANCY BARNETT

Nancy Barnett, 85, was born in Greenwood, lived in Yancey Mills and now resides at Mountainside Senior Living in Crozet.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

From the estate to the bread line

Nancy Barnett

Born 1924

Grew up in Greenwood

"I remember early on my daddy standing in the line getting food," says Nancy Barnett. "We looked forward to it." Her father, Morton Whiting, worked at Mirador, childhood home of the iconic turn-of-the-century Langhorne sisters– Nancy, Viscountess Astor and Irene the Gibson Girl– where he made $2.50 a day.

Barnett's father went every Saturday to Charlottesville to the bread line, and once a month, clothes were distributed as well. "I had new shoes," says Barnett, smiling at the memory. "We had so little. I remember going to school with paper in my shoes."

Her parents had 10 children, and her grandmother lived with the family as well. "We were fortunate," says Barnett. "We had a cow and had milk, and chickens and had eggs."

Finishing school meant going through the seventh grade. "Daddy made all of us finish the seventh grade," says Barnett. "I wanted to be a math teacher, but I couldn't afford it."

During World War II, the U.S. Army recruited nurses through the Cadet Corps. Barnett signed up. "I thought I was wealthy getting $15 a month," she says.

Her advice as a Depression and segregation survivor: 'Take advantage of the opportunities because our people don't always."

And as grateful as she was to the bread lines, says Barnett, "I don't eat oatmeal or Jello now."

As a lad, Boots Mead was torn between his love of piano– and playing with the neighborhood kids.

PHOTO COURTESY ERNEST MEAD

Ernest Mead has an endowment set up by his adoring students at UVA.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Tulle crisis

Ernest "Boots" Mead

Born 1918

Grew up in Richmond

"We were of modest means," says UVA professor emeritus of music Ernest Mead, 90. His father was a vice president of Richmond Paper Company, and while the Mead household was more affluent than many, he remembers the economies they had to take.

Musical prodigy Mead played the piano at age four. "My mother sent me to a very fine teacher when I was eight years old," he says. "I was aware of the fact we had to count our pennies because things were tight."

They lived on Richmond's West Avenue where there were a lot of youngsters Mead's age, many of whom went to private school. "I asked my father why I didn't," recalls Mead. "He said we didn't have money for that. I went to public schools always."

Young Ernest loved to play with his friends after school, but part of the deal with his piano lessons was that he practice every day from 5:30 to 6– just when the afternoon games "were going great guns," he says.

"One day I was late coming in," confesses Mead. "Mother said she had to really work to find the money for these lessons. She said, 'I'll pay for the lessons, but you'll have to do your part and practice at 5:30. And if you don't come in, I'll stop your lessons.' She never had to say another word."

He remembers overhearing his parents talking about the high cost of groceries. One way his mother earned extra cash was with her iced angel food cake. "She cut it in pieces, wrapped them, and took them to the drugstore at the corner of Grove and Lombardy," an intersection in Richmond's Fan district, he recalls. "They were well known."

And then there were his two older sisters, who had lots of parties to attend that required party dresses. "My mother didn't pride herself on being a seamstress," chuckles Mead. "But she made dresses for special occasions," such as his sisters' debuts. "We didn't have the money to go out and buy them." One gown required tulle, the fine net material used on party dresses and tutus.

"Mother ran out and went to [department store] Miller & Rhoads," he says. "They refused to let her charge it because her bill was too high. Mother grew up with Webster Rhoads. She went to his office and said, 'My daughter needs tulle for this party in a few days.' He said, 'Take whatever you need.'"

Mead still remembers the parties, especially the debutante parties. "They were fantastic, luxurious," he says. "Someone around there had money."

Sylvia Beckman Warner graduated high school in 1929.

PHOTO COURTESY SYLVIA WARNER

Sylvia Warner, 97, now lives in an art-filled apartment at the Colonnades.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The Nazi situation

Sylvia Warner

Born 1911

Grew up in Naperville, Illinois

Sylvia Warner still remembers how the Depression affected her family's fortunes and her year studying abroad. "My sister Eleanor went to Oxford in 1929," says Warner. "She had a very different experience. She stayed at the Savoy. I lived in a boarding house."

Warner, nee Beckman, sailed steerage on the S.S. Dresden ("It sank on its next trip," she interjects) to England in 1933 to study at the London School of Economics. Adolf Hitler had just been elected chancellor in Germany, and the National Socialist German Workers Party was on the rise.

"There were quite a lot of Nazis at L.S.E.," notes Warner, 97. When Professor Harold Laski criticized the movement, Nazis in the class would "boo at him. We'd boo at the Nazis. It was a very sensitive time.

"I took one of the Nazis to a lecture," she continues. "Bertram Russell was our usher, and Aldous Huxley was onstage. I had this Nazi sitting beside me, and he kept wanting to get up and heckle."

Despite living in a boarding house and traveling third class, the London School of Economics was a deal at $81 a semester. Warner, who had $1,500 for her studies abroad, spent the Christmas holidays in Germany and spring break on the Riviera.

Her friend's father in Koln was a director of the Reichsbank. "They had servants who were Nazis," says Warner. "We had to whisper." And when she went with her friend to Koln University, she remembers brown-shirted young men and people heil Hitler-ing all over the place.

When traveling third class, Warner seemed to have a knack for being able to upgrade her dining. On the way from Marseille to London, she ran into the Bishop of London, who invited her to tea in first class. Wanting to reciprocate the hospitality, "I invited him– the Bishop and his family– down to third class," says Warner.

In London, she ate sparingly, having an apple for breakfast, a vegetable for lunch, and going to a restaurant for spaghetti for dinner.

The family finances prevented her from finishing her degree in international law and international relations at the London School of Economics, and she returned home summer of '34. She cabled her father that she would have 25 cents when she arrived in New York. "I was so used to going third class, I took the bus, not the train, to Chicago in July." And when her family met her in gay attire, "They were looking like a garden party," says Warner.

She worries about how the current hard times are going to affect students. Her advice is to not buy a lot of new clothes but to make over old ones instead. Warner looks askance at gym memberships. "Do your exercise at home," she instructs. "I do."

She thinks children get too much for allowances, and people should make budgets. Warner's time living in boarding houses proved to be good practice. She married her first husband, artist Norman Wright, in 1935, and they lived "very frugally" in a one-room apartment. They kept a budget for two years, "then we threw it away because we didn't agree."

In 1940, the Wrights moved to a dairy farm in Vermont, and she was elected to the Vermont General Assembly in 1944. An artist in her own right, Warner exhibited twice at the Art Institute of Chicago.

One of her sisters, now deceased, lived in Northfield, Illinois. "We decided we'd like to spend our later years together," says Warner, who'd lived in the Washington area after Vermont. Someone gave her brochure for the Colonnades, a retirement community on Barracks Road, and she moved here in 1993.

Eugene Williams' mother, Septimia, worked 12 hours a day as a domestic. She was known as Seppie and is photographed with Eugene around 1939.

PHOTO COURTESY EUGENE WILLIAMS

Brothers Albert and Eugene Williams in the early 1930s.

PHOTO COURTESY EUGENE WILLIAMS

The house Eugene Williams lives in now has indoor plumbing, unlike his childhood home a few blocks away on Dice Street.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Already poor

Eugene Williams

Born 1927

Grew up in Charlottesville

The house in which Eugene Williams grew up on Dice Street, two blocks from the C&O railroad tracks, was nice looking, even though it didn't have indoor plumbing. He remembers the hobos, who would get off the train and come up the hill to the African-American neighborhood where he lived. "They were white people," he says. "They'd beg us for a sandwich."

His mother and father counted pennies, and knew exactly how much food would cost: a small loaf of bread was 5 cents, a large one 10 cents, and hot dogs, hamburger, and bologna were 20 cents a pound. "At my house, we'd buy a half pound," recalls Williams, 81.

His father died when he was 10 years old, and his mother worked from 7am to 7pm. "I thought this was the way it was," says Williams. "Later, I heard we were coming out of a Depression. It didn't get better for us."

Williams is adamant that some blacks today are facing a depression– not a recession. "When you're making minimum wage and paying $2.70 for a loaf of bread, and $2 for a half gallon of milk, when senior citizens can't buy food because they have to pay for medicine, it's a depression," he says. "Any time you cannot have money from one payday to the next, when in two to three weeks you've spent the whole paycheck, that's depression."

The Williams family founded a company called Dogwood Housing, which was dedicated to the ideal of decent, affordable housing in mixed-income neighborhoods, rather than the ghettoization of the poor. They sold their 78 rental units for $6.4 million in 2007.

Joyce Colony had the woods and fields as her playgrounds and relied on imagination-fueled entertainment.

PHOTO COURTESY JOYCE COLONY

Don't offer Joyce Colony cooked carrots– she had enough of them during the Depression, when salad consisted of field greens and iceberg lettuce came much, much later.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Eat your vegetables

Joyce Galbraith Colony

Born 1928

Grew up in Roanoke County

Her father was an electrical engineer who opened a shop to repair big motors. When State and City Bank in Roanoke failed, he lost $800– "All the money he had in the world to run his business," explains Joyce Colony. "[The bank] never reopened, and he never forgave Franklin Delano Roosevelt."

Her parents heated the Franklin stove with the 50-cent bags of coal because they didn't have enough money to buy a ton.

She remembers a diet heavy on dried beans, and going out to pick wild mustard greens. "We had a lot of carrots and potatoes," which were boiled together, says the resident of Ivy's Glenaire subdivision. "I despise cooked carrots."

And there was occasionally chicken, if you had them. "Mama killed them with an ax," says Colony, 80, pointing out, "They'd run to the woods headless."

Barter was big in the Depression when people couldn't afford to pay cash. (That's how the Barter Theater in Abington, where people brought food for the actors, got its name.)

One man owed Colony's father $50 for fixing his motors, and in payment built a log playhouse for Colony and her sister. "We played and played and played in that," says Colony. "It lasted."

Her mother sewed all the children's clothes. "I didn't ever wear feedsack," says Colony, "but some of my schoolmates did."

Shoes were polished and fixed, and everything was handed down. "To this day," says Colony, the elder sibling, "my sister doesn't want anything from me."

Colony believes people living on farms fared better during the Depression. "We never felt poor," she says. "We had plenty to eat, and we ate what was put in front of us. We had fields to run in and friends and the playhouse."

On the heels of the Depression came World War II and December 7, 1941, "We went to the Roanoke Times & World News building to wait for the afternoon paper," says Colony.

The war brought Victory Gardens, hoarding, and the collection and recycling of scrap metal– even the wrapping paper from chewing gum was collected for the war effort. "Most people feel we pulled out of the Depression because of the war," says Colony.

"Many of the older people had been poor and they knew how to deal," observes Colony. "People now don't know how to be poor."

Daisy Sandridge remembers her aunt giving her a penny to take to church, and tying it in a hankerchief.

PHOTO COURTESY DAISY SANDRIDGE

Daisy Sandridge advises young people to climb the ladder one rung at a time and save for a rainy day.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Grandfather made moonshine

Daisy Hall Sandridge

Born 1931

Grew up in Boonesville

The doctor arrived on horseback to deliver Daisy Sandridge, and she points to the window in a picture of the Boonesville house where she was born.

Her parents left Daisy in Boonesville with her grandparents, Lucy and James Walton, and took her younger brother and moved to Maryland so her father could get a job with Bethlehem Steel. "That was to keep from starving," says Sandridge. "There was no work."

Nor was there indoor plumbing, electricity or paved roads. "What people ate, they raised," trading for things they couldn't grow like coffee, says Sandridge. "My grandfather made moonshine whiskey. It was a way to add income. People can't believe today that you didn't have a cent."

Her parents were so poor, "My brother and I stood up to eat because my parents only had two chairs," she says. She played with a paper doll, and if she got one toy at Christmas, that was a big deal.

As an adult, Sandridge worked as a secretary at Acme visible Records in Crozet. Her husband, William Davis Sandridge, started the Jefferson Journal. "We had the first black-and-white television in Crozet," she says. "We came up so poor. When you look at where we came from... I wish everyone had the experience of climbing the ladder and saving for a rainy day. Now, they want everything first class."

Ruby Robertson, holding the baby, remembers her mother saying, "We're poor, but we're proud."

PHOTO COURTESY RUBY ROBERTSON

"Money doesn't make anyone happy," says Ruby Robertson. "What you do for others is so important."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Self-educated, self-reliant

Ruby Robertson

Born 1914

Grew up in Campbell County

Ruby Robertson, 94, describes how farmers plowed big fields without the convenience of a tractor. The first time was with a turnover plow to break the ground, the second time was with a harrow to break up the clods, and the third time was to lay out the rows.

She knows– her father was a sharecropper who would resole his 10 children's shoes. They raised all their own food, and her mother made all their clothes. "She'd look at them in a magazine, and she'd make them like that," says Robertson. Her mother died when she was 13

"We had always worked hard," says Robertson. Her first job was at a cotton mill in Lynchburg working 12-hour shifts for $6 a week. She got married at 16 1/2 and her husband earned a dollar a day at a sawmill.

The couple moved to Alexandria, and Robertson worked nine years as a nurse's aide, then passed a test to become a licensed practical nurse.

She remembers having sugarplums at Christmas, and her biggest thrill as a child: "I saw Santa Claus." As for today's parents, "They do their children such a disservice when they pile so much in front of them and every day is Christmas." she bemoans.

"If you took young people today and gathered them up and took them back in time and had them go through for a week what we had to do to survive, they couldn't do it," assesses Robertson.

Jo Marsh was a student nurse at Blue Ridge Sanatorium to earn money for UVA nursing school.

PHOTO COURTESY JO MARSH

Jo Marsh's Depression-era thrift allowed her to travel during her retirement.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Depression Psychosis

Josephine May Marsh

Born 1918

Grew up in Fluvanna County

Jo Marsh still has a picture of the gracious house at Cedar Ridge Farm that was built in 1853 and had 20' by 20' rooms. "I thought we were better than other people because father bought and paid for the farm," she says. But her father had to take out a mortgage to buy seed to get the crops in the ground, and he never was able to pay it off until her brothers did as adults.

Her mother was an educated woman– and she made clothes for her six children from feedsacks made of unbleached muslin. She also took care of the garden. "My mother canned all summer long," says Marsh. "We canned and canned."

Although Marsh wanted to be a librarian, she started working at age 18 in 1936 as a student nurse at the Blue Ridge Sanatorium to earn the $100 she needed to go to nursing school at UVA.

"I never really realized it was a Depression until I took a sociology class at UVA," says Marsh. She recites the three signs of "Depression psychosis."

1. Never give up a job unless you have another.

2. Never throw anything away. Save it because you might need it or use it until it's worn out.

3. Never buy anything you can't pay for with cash and never go into debt.

"The only thing my husband and I went into debt for was a house, and we paid it off quick," says Marsh. Her advice to the softest generations: Stay out of debt and save 10 to 15 percent of your salary.

Marsh worked as a nurse for 30 years and banked her salary. And when she retired, she traveled all over the world.

Francis Fife milked the cows that resided in his family's pasture.

PHOTO COURTESY FRANCIS FIFE

Saving is still a good idea, despite government admonitions to spend to help the economy, says former banker/mayor Francis Fife.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Finance 101

Francis Fife

Born 1920

Grew up in Charlottesville

The biggest memory of the Depression for Francis Fife was people coming to his house asking for food. "Your house got marked if you gave food to people," says Fife. "There was a hobo camp near us. I remember my mother couldn't help handing food out the back door. It got to be quite a burden at times. We were not rich."

Fife, who went on to become a banker and a Charlottesville mayor, grew up in the Fife family home built in 1822, which was "imposing," he concedes. In the community pasture around the house, people paid to keep their cows there– $2 a month for six months a year, a total of $12 a cow per year. "I had to work on the fences," remembers Fife. "I couldn't calculate whether my father spent more on the fencing than he made."

A lot of the neighbors worked on the railroad.

"I had to milk the neighbor's cows when the husband went on the railroad," says Fife, recalling a troublesome heifer who would kick over the milk bucket, a move that required him to head back the house to sterilize the bucket.

"My father was in the insurance and real estate business, and that drifted away to about nothing," says Fife. "He got a job with the WPA as administrator for eastern Virginia."

His father died in an automobile accident in 1937– the same year Fife entered UVA with the proceeds from his dad's life insurance– "not much," says Fife– and his mother kept the house that Fife still lives in. "I do remember one meal she said, 'These are navy beans. They're four cents a piece, so eat them all up,'" he says.

One major difference between now and then: If people had money, they tried to save it, says Fife. Now, if someone buys a house they can't afford, they expect to be bailed out, and if they're given money, they're told "to go spend it to help the economy," says Fife. "It sounds crazy."

He sees one educational area that needs help. "People," says the retired banker, "need to know about finances."

UPDATE 2/16/09 The spellings of Richman Brothers Clothes and Bertrand Russell's first name have been corrected.

UPDATE 2/19/09 Josephine Marsh was a student nurse when she worked at Blue Ridge Sanatorium.

#