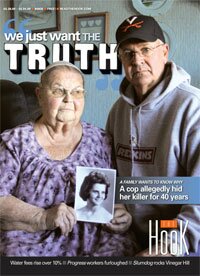

COVER- 'We just want the truth': Connie Hevener's family wants to know why a cop allegedly hid her killer for 40 years

Though Staunton police say Connie Hevener's 1967 murder was solved this past November, many unanswered questions remain for Hevener's mother LaVerne Sowers and twin brother Carroll Smootz.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

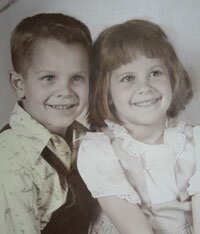

MOUNT SIDNEY– On April 30, 1947, Virgil and LaVerne Smootz became parents to twins: a girl Connie, and a boy Carroll. "From the very beginning," says LaVerne of her inseparable twins, "they were peas in a pod."

"I needed her, too," says Carroll, "she was always the one keeping me out of trouble."

If Carroll missed class, Connie lent him her homework. If Connie joined the high school cheerleading squad, Carroll joined the football team. If one developed a crush, the other would give a thumbs up or thumbs down.

It might have been this way for 62 years. But as the family sits around LaVerne's living room, thumbing through a family photo album, in the Shenandoah Valley town of Mount Sidney, the family consists only of LaVerne (now LaVerne Sowers) and Carroll. Virgil died 28 years ago. Connie died much earlier and much younger, in a crime that continues to plague the Valley.

One spring night in 1967, Connie had been married nearly two years to Larry Hevener, and was working at High's Ice Cream on North Augusta Street in Staunton's Terry Court shopping center. That night, at just after 10pm, Hevener and her co-worker and sister-in-law Carolyn Perry were closing up shop when the moment came that would not only change the Smootz family's life, but the life of a city.

When a passer-by found the two young women, both were bleeding heavily from the head. Someone had shot them both at point blank range with a .25 caliber pistol. They both died that night.

Hevener was 19 years old.

It took nearly 42 years to find out who pulled the trigger. On November 28, 2008, Sharron Diane Crawford Smith, a co-worker at the store at the time of the killing, confessed as she lay dying in a local nursing home, her kidneys failing. She died before ever seeing the inside of a courtroom.

In her confession, Smith said the lead investigator on the case, Staunton police sergeant Davie Bocock, not only knew that she had committed the crime, but had helped her elude justice by burying the murder weapon.

Bocock died in 2006 at the age of 76.

Now, with no hope of either Smith or Bocock ever paying back any debt to the families or to society, Sowers says she and her son want the only thing that can help them bring any closure to their nearly 42-year nightmare: "We just want the truth."

'Something has happened to Connie'

The night that changed both Sowers and Smootz's lives forever began at around 11:30pm on Tuesday, April 11, 1967.

"We were living over in Harrisonburg," says Sowers, "and I got a call from my sister Gwendolyn telling me to come to her house in Staunton."

Her son Smootz got a similar call, and while both understood something serious had occurred, they say they expected to see Connie at the house along with the rest of the family.

"I figured something had happened to [Connie's husband] Larry," says Sowers. "Or Connie had been talking like she might be pregnant, so I thought she might have miscarried."

As Sowers prepared herself to console her daughter, she saw something out of the passenger's side window of her sister-in-law's car.

"We came down Augusta Street," says Sowers, "and outside High's, I saw all these lights, and I looked, and there were more police cars than I'd ever seen."

In an instant, the resolve she had been building to comfort her daughter disappeared into a wave of panic.

"I turned to my sister-in-law," says Sowers, "and said, 'Oh, no, something has happened to Connie.'"

Upon arriving at her sister's house, her worst fears were realized.

"I told her," says Smootz, "'Mama, Connie's been shot, and she's dead.'"

At that moment, reality for Sowers ground to a halt.

"I didn't say anything," says Sowers. "I was just in shock. They asked me, 'Did you hear what he just said?' I didn't say anything for about 15 or 20 minutes."

Then came the sad duty of informing Connie's husband Larry and her father Virgil, both of whom were working as long-haul drivers for a Staunton-based trucking company called Smith's Transfer.

"Larry was in Massachusetts, and Virgil was in South Carolina," says Smootz. "I just told the main dispatcher to tell them what had happened and to get on a plane back here. I didn't want them driving those trucks all the way back, being all alone."

With $138 missing from the register at High's, police suspected robbery. But days after her death, Smootz was going through his sister's belongings when he found a note in her purse and immediately realized her sister was no random victim.

"I found a note on a small piece of paper," says Smootz. "In her handwriting, she had written very neatly, 'Tell Larry I love him.' She knew something was going to happen to her."

40 years of aftermath

With this information, as with all the material he thought might be helpful in solving the crime, Smootz went to Staunton police investigator Davie Bocock.

For three months, Smootz says, he went to Bocock on a regular basis. However, he grew increasingly frustrated with Bocock for not catching his sister's killer. Smootz says this was partly due to his own personal grief, but also to a genuine belief that Bocock was not doing all he could.

"Sure, I was angry," says Smootz, "but even as someone who has no police background, I knew they were dragging their feet. I asked Bocock if they had searched the area around the store for a gun, if they had checked the drains near the store for shells, if they had even asked the people who worked at High's for information. He hadn't done any of it.

"If it had been his daughter," says Smootz, "he would have been all over it. But we were just regular people, so he didn't care."

This anger at the police came to a head one day that summer when Smootz came back to his car, parked on the street in Staunton, to find a ticket on his windshield.

"I walked right into the police station, right over to Bocock," recalls Smootz, "and said, 'Is this how you're spending your time? Writing $50 parking tickets when you should be finding out who killed my sister?'"

Bocock tore up the ticket and told Smootz to be on his way.

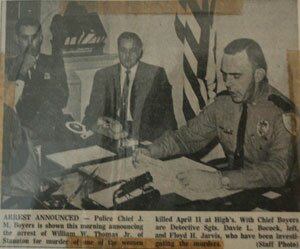

Finally, in October, a little more than six months after the night of the murders, Staunton police arrested William "Gus" Thomas, a 24-year-old former high school teacher in nearby Swoope. With the arrest came a meeting between Bocock and Smootz in which Smootz says Bocock applied to him the kind of treatment he wished he'd applied to potential suspects.

"Bocock sat me down," says Smootz, "and said if Thomas so much as fell and broke his neck, if he so much as had a heart attack, he would throw me in jail and throw away the key."

Sowers' impression of Bocock was better than her son's, but she still thought it was strange that in the half-year investigation that led to the arrest, neither Bocock nor any officer had asked her about what she knew about her daughter.

"He was kind and considerate to me," says Sowers, "but he never asked me about anything. I just took his word for it that they knew what they were doing, and when they got Thomas, I thought they had the guy."

A Staunton jury disagreed. In the trial the following year, prosecutors couldn't produce a murder weapon, nor could they place Thomas at the scene of crime. The top evidence they had was testimony from several Staunton residents who claimed Thomas had confessed to the crime in private conversations.

It only took the jury three hours to return a verdict of not guilty.

The outcome was a difficult one to take for Sowers, but ultimately one with which she had made her own personal peace.

"I knew God had a reason," says Sowers, "and I knew God wanted me to forgive him."

Smootz says today he had a harder time summoning any feelings of forgiveness, particularly on one day in the summer of 1968.

'Temporarily blinded'

With the trial finished in March of 1968, nearly a year after his sister's killing, Smootz still lay awake late into each night.

"I had to constantly keep my mind occupied," he says. "When I couldn't get to sleep, I had to train myself to add, subtract, and divide in my head, just to have something to do. Every time my mind stopped racing, all I could see was Connie's blood on that black-and-white tile floor."

Much as he found fault with Bocock's investigation, Smootz felt that police had gotten their man only to let him get away. He knew that Thomas had been tried for only one of the two killings, a gambit townspeople figured left prosecutors with another chance if new evidence appeared.

"I just hated Bill Thomas," says Smootz. "I hated him for making me an only child after 19 years of having that connection only twins have."

Smootz had not seen Thomas since the acquittal when he went out for some groceries on one hot, bright day in the summer.

"As I walked out of the IGA," says Smootz, "I saw him walking out of the ABC Store."

So as he started up his car and put it in drive, Smootz began tailing Thomas, still on foot.

"I was almost touching the back of his legs with my bumper," says Smootz. In his left hand, he held the steering wheel. In his right, he held a knife.

"It was about nine inches long," says Smootz. "When I was out on long hauls, I used to keep it in my truck to cut open watermelons."

As Smootz's pulse quickened, he took a quick look out his window as he pulled up alongside Thomas.

"For a split second," says Smootz, "a voice said to me, 'Maybe it isn't him.'"

With that thought, Smootz continued to drive past the man. Still, a few seconds later, Smootz couldn't resist looking in his rearview mirror to get a look at the face.

"It was Thomas after all," says Smootz. "So I threw it in reverse and went as fast as I could."

But the moment had passed. Thomas was then safely ensconced in his car and leaving the parking lot.

Forty years after that day, Smootz looks back at his former self in horror.

"That day haunts me," says Smootz. "What if I'd gone off the deep end? I'd have ruined my whole life then and there, because if I'd gotten to him, I'd have killed him."

So what made Smootz doubt his eyes for long enough to keep him from making the biggest mistake of his life? Smootz says the only explanation that makes sense to him is divine intervention.

"Either God temporarily blinded me," he says, "or it was Connie keeping me from doing it."

The memory came rushing back last year when he found out that if not for his moment of uncertainty, not only would he have killed a man; he would have killed an innocent man. Thomas, who now lives in Pennsylvania, was finally absolved of any culpability for the crime in December after Smith made her confession.

Deathbed confession

It was late November 2008 when Smootz, Sowers, and the rest of Hevener's family along with the family of Carolyn Perry– Hevener's slain co-worker– learned from Staunton police that they had a new suspect.

In August, Verona resident Joyce Bradshaw told Staunton police of a conversation she'd had 10 days before the murder with co-worker Sharron Diane Crawford.

"Diane was one of my aides at Western State Hospital," says Bradshaw, now 74, "so we had been acquainted at work, and she had always treated me okay."

Bradshaw describes Crawford as having been the ultimate tomboy, even into her late teens.

"If you saw her far away, you probably thought she was a boy," says Bradshaw. "She wore her hair real short, she always wore pants, she hunched her shoulders like a football player."

Bradshaw says she didn't socialize with Crawford outside of work, so she was surprised when she got a call, on or around the night of April 1, 1967.

"She said she wanted to go get a hamburger," says Bradshaw.

Sitting in Crawford's car in the parking lot of the Kenny Burger on Greenville Avenue near Bessie Weller Elementary School, eating dinner, Crawford began a fateful conversation, a conversation that Bradshaw would be unable to forget.

"She told me to open up the glove compartment," says Bradshaw. "So I did, and inside there was a pistol."

Then came the words that Bradshaw couldn't get out of her mind for nearly 42 years.

"Diane says, 'There's two bullets in that gun,'" Bradshaw recalls. "'One of them's for my stepfather. The other is for the Hevener girl on Grubert Avenue.'"

Asked why she had waited 41 years to reveal this truth, Bradshaw said that she hadn't waited at all.

"I went to the police the day after the murders," says Bradshaw. "I went straight to Davie Bocock."

Nearly four months months later, on November 28, 2008, Staunton police investigators were at the bedside of Sharron Diane Crawford Smith, then 60 years old and suffering from the end stages of kidney failure in a nursing home in Harrisonburg. According to transcripts of the interview, Smith told police that Hevener had been "taunting, teasing" her. Said Smith, Hevener had been picking on her "about my lifestyle," confirming to police that this was about her being a lesbian.

Additionally, she said stepfather Emmett Bradshaw had been physically abusing her for years because he disapproved of her sexuality. One day, she decided she just couldn't take it anymore. Crawford's stepfather Emmett Bradshaw died some time in the 1980s of natural causes, according to the Staunton police chief.

On April 11, 1967, after having made sure Hevener would take over her late shift at High's that night, Smith allegedly confronted Hevener with her .25 caliber pistol.

"I was just pushed so far," Smith told police, "so I shot her, and that was it."

To serve and protect

On December 12, 2008, Staunton police chief James Williams held a press conference to announce Smith's arrest for the murder of Connie Hevener and Carolyn Perry.

"This," said Williams, "effectively closes the case."

Smith was to make her first court appearance three weeks later, on January 6, 2009, but that hearing was postponed due to her failing health. Thirteen days later, Smith died from her illnesses.

Staunton police had, however, questioned Smith twice more between her arrest and death. On December 30, 2008, Smith finally told police why she had been able to remain hidden in plain sight for so long: she had help from her "pretty good friend" in the Staunton police department, Davie Bocock.

Bocock and Smith were already familiar with one another through mutual friends, and the 37-year-old Bocock had taught the 19-year-old Smith a new extracurricular activity out at his farm: target shooting.

The two, Smith said, would shoot at pictures of "deer and stuff" typically placed against bales of hay. Asked by police how frequent these training sessions were, Smith said, "I'd say we went right much."

Smith also admitted that several days after the murders, she and Sergeant Bocock met in the Dairy Rite parking lot on Greenville Avenue, where Smith says she showed him her .25 and said, "I had shot the girls."

According to Smith, rather than slap cuffs on her for Staunton's crime of the century or advise her to avail herself of an attorney to come forward to another police officer, the man heading the murder investigation simply took the gun from Smith and helped her hide it on his farm.

"He put it in a box," said Smith. "He said he was digging a hole, and putting it in there and that it was safe."

In January, it briefly seemed possible that Staunton police had found the murder weapon when, hours after a January 28 press conference, the wife of a deceased Staunton cop turned over a .25 caliber pistol she said originally belonged to Bocock. Ballistics tests on that weapon, however, came back negative on February 17.

Smith said that of all the people she had known in her life, including her eventual husband, her three children, and the longtime companion with whom she lived in her later years, Bocock– who died in 2006 at the age of 76– was the only person she told about the murder until 2008.

Risking it all

At this point, with both Smith and Bocock dead, it may be nearly impossible to know for sure what could have motivated Bocock to allegedly cover up Staunton's most infamous crime. None of Bocock's three children, nor his half-brother returned the Hook's repeated calls for comment. However, according to Dr. Bruce Arrigo, a professor of criminal justice at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and expert on the psychology of corrupt police officers, it takes a special sort of relationship for a cop to cover up somebody else's crime.

"It's less a question of corruption and more a question of an ethical dilemma," says Arrigo. "It would have to be the kind of relationship with a deep and compelling history."

A February 1 article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported the possibility of "a romantic triangle that involved Bocock." According to Bradshaw, Bocock did have the reputation of being "a ladies' man."

"I never liked talking to him," says Bradshaw. "He had the smirking smile and the dancing eyes that just make a woman feel uncomfortable."

But would a shared interest in firearms really lead an alleged flirt like Bocock to seduce a closeted and allegedly masculine lesbian like Crawford? According to Arrigo, it takes more than romance to lead a cop to risk his career by covering up a homicide.

"This would have to be something like a marriage," says Arrigo, "or a parent-child relationship."

Father figure

Could it be that the reason Davie Bocock protected Sharron Diane Crawford Smith was that Bocock was Smith's father? Evidence is scant, but circumstances don't rule it out.

Smith's obituary in the January 21 edition of the Staunton News Leader states that, "She was born August 21, 1948, in Staunton, a daughter of Delphia "Red" (Crawford) Bradshaw." There's no mention of Smith's father.

There's no publicly known evidence suggesting any out-of-wedlock patrimony for Bocock, but he was living in his native Staunton and had just turned 18 at the time of Smith's birth.

As he had announced at a January 28 press conference, Staunton police chief James Williams says his department continues to work along with the Virginia State Police to investigate Smith's deathbed claims. Williams would neither confirm nor deny that his department is looking into the father-daughter angle.

"We hear rumors just like you guys," says Williams. "Sometimes the talk could have some truth, and sometimes it doesn't. We're just trying to determine what could have been the relationship between the people involved in this case."

The Hook attempted to obtain a copy of Smith's birth certificate from the Virginia Department of Records in Richmond. The request was denied, with a department representative informing that such records were only open to family members.

Additionally, the Hook tried to contact Bocock's three children, Bocock's half-brother, Smith's daughter, and Smith's longtime companion in an attempt to learn more about the relationship between the two. None of them returned the calls for comment.

It turns out, however that Smith's mother lives in Salem. Reached by telephone, "Red" Bradshaw told the Hook of her recently late daughter, "She's been accused of a lot, but I have nothing to say."

A reporter asked who Smith's father was, but Bradshaw hung up the phone.

Searching for closure

Despite the fact that they finally know the name of their loved one's killer, Hevener's mother Sowers and brother Smootz say they won't be satisfied until they know why they had to wait more than four decades for any semblance of closure.

"The police dragged their feet," says Sowers. "I feel like they need to tell us why."

Smootz's anger is so palpable that he expresses it as though the object of his ire for four decades is still wearing a badge and walking a beat.

"I want Bocock," says Smootz. "For 42 years, we went through all kinds of pain and suffering because we didn't know. I have no sympathy for him or his family if they have to suffer a little."

Nevertheless, Sowers says that her Christian faith compels her to forgive Bocock.

"Jesus says we have to forgive," says Sowers. "Otherwise, he won't forgive us."

That's not to say she doesn't resent Smith. She refused to meet with her as other family members had after her confession.

"I just couldn't do it," says Sowers. "I didn't want to see her."

Additionally, she disputes Smith's assertion that her daughter teased Smith about her sexuality.

"I think she may have pulled her aside," says Sowers, "and tried to get her to start living right. Or maybe she came on to Connie, and she didn't want any part of it. But my daughter was not the kind to tease people because they were different."

Smootz freely admits that when it comes to the woman who took the life of his "guardian angel" Connie, and those who stood in the way of bringing her to justice, he doesn't have what it takes to turn the other cheek.

"We have all carried this burden differently," he says. "Some of us have been stronger than others."

But even if he does learn the whole truth of what happened in 1967, Smootz says one thing will always remain the same.

"I was her protector," says Smootz, "and I let that happen to Connie."

With these words, Smootz begins to tear up. Sowers turns to Smootz and says, as only a mother can to her son, "You know it's not your fault."

"I know," says Smootz, "but I still blame myself."

Carroll and Connie at age 6.

COURTESY OF LAVERNE SOWERS

Mother and daughter smile for the camera on Connie's wedding day, along with father Virgil Smootz and husband Larry.

COURTESY OF LAVERNE SOWERS

LaVerne Sowers keeps newspaper clippings about her daughter's murder in the same scrapbook as the pictures of Connie's childhood.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

On October 16, 1967, Staunton police investigator Davie Bocock (left) watches while police chief J.M. Boyers announces the arrest of William "Gus" Thomas for Hevener's murder. A jury would later acquit Thomas in three hours in 1968.

STAUNTON NEWS LEADER

More than 41 years later, on December 12, 2008, Staunton Commonwealth's Attorney Ray Robertson and Staunton police chief James Williams announced the arrest of Sharron Diane Crawford Smith. Smith would later say that Bocock helped her bury the murder weapon on his farm.

STAUNTON NEWS LEADER

Sharon Diane Crawford Smith (seen at left in her 1966 high school yearbook picture and at right in her 2008 police mugshot) told Staunton police she killed Connie Hevener because she had been "taunting, teasing" her "about my lifestyle" as a closeted lesbian.

STAUNTON NEWS LEADER/STAUNTON POLICE DEPARTMENT

At a recent visit to his mother's house, Carroll Smootz thumbs through a collection of pictures of his twin sister, Connie Hevener, with his mother LaVerne Sowers. Hevener was murdered in 1967, at age 19.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

#

4 comments

Connie Hevener's family wants to know why a cop allegedly hid her killer for 40 years? Because that's what crooked corrupt cops do. It's that simple. And every small department nationwide has at least one or two of them aboard. Larger cities... God only knows how many they have!

Lindsay, I would like to see a story and interview of William "Gus" Thomas.

I can't imagine being charged with a murder and going to jail for a crime you didn't commit. Can you imagine the mental anguish this man suffered between the time he was arrested and finally released by a jury?

I often wonder, did he sue the city and Bocock for false arrest and imprisonment?

I've wondered for weeks and weeks if Bocock could have been her father - and you have added credence to my speculation. Only a parent will fight tooth and nail to protect their child from something like this. Wish DNA testing could be done somehow to shed light on this theory.

quote: Sick Of The Local Rambos

January 24th, 2009 | 7:25 pm

B Kelly, I think in the movie version of this story Bocock will be a married cop having an affair with a married woman. This other woman gets pregnant by him. Neither Bocock’s wife or the other woman’s husband ever know that Smith is actually Bocock’s daughter by this woman he was having an affair with. A father could never charge his own daughter with a double murder. :)