COVER- Inside the mind of a scam artist: the mini-Madoffs among us

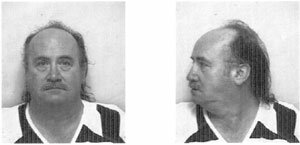

A motorcycle racer who launched a youth basketball team, Donnelly was "generous" with his time and money, says friend Mike Ratliff, who founded a youth basketball team with Donnelly and says he is "shocked" by his friend's arrest.

PHOTO COURTESY DONNELLY FAMILY

Investigators say a Central Virginia man bragged about an astrophysics-influenced financial method called "Blue Logic," but to at least one man who handed money to John M. Donnelly, the reality was nothing to boast about.

"It's just a typical Ponzi scheme that ran its sad course through a tight knit group of otherwise business-savvy friends," says alleged victim Sam Fleming.

If you didn't know what a Ponzi was three months ago, you probably do now. For the second time in a decade, a multi-million-dollar fraud was allegedly centered in the Charlottesville area. This time the accused is a middle-aged motorcycle racing enthusiast arrested in mid-March by federal agents and charged with bilking over $11 million from investors, many of them friends and former motorcycle racing teammates.

What motivates the scam artist? What leads investors to believe the unlikely promise of consistent high returns?

***

David Marotta, center, warns to avoid lavish-livin' financial advisors, and that pride often goeth before a financial fall.

PHOTO BY TOM LOACH

Don't want to be swindled? David Marotta, president of Marotta Wealth Management and financial columnist, offers these suggestions for safeguarding your money.

1. Don't let your financial advisor have custody of your money. And when making an investment, make the check out to the custodian of your account, not your advisor.

2. Walk away from anything too good to be true. John Donnelly allegedly promised his investors returns of up to 22 percent annually. Too good to be true.

3. Insist on publicly priced and traded investments. Illiquid investments are hard to price and to calculate your return. How to tell if it's illiquid? Buy the asset, hold it for a week, and then try to sell it. If it loses a bundle, it's not liquid.

4. Buy investments that trend upward. Forget selling short, and stay away from a commodity like gold, which can fluctuate wildly and, over time, on average does not appreciate in value.

5. Understand your investment strategy. Don't trust any investment strategy you don't understand, and don't trust any advisor who won't or can't take the time to explain exactly why and how he or she operates. Blue Logic?

6. Recognize and avoid financial hooks (not to be confused with the Hook): Class B shares that have a high expense ratio and charge if sold before a certain period. Whole life insurance with a surrender value significantly lower than its market value. Certain annuities that tie up your money. Private equity and hedge funds that hold onto your cash for years.

7. Avoid investment advisors who won't tell you how bad the market can be. Investors should always be aware of risk and promises of earnings without loss are unrealistic and take up us back to number 2.

8. Avoid an advisor with a lavish lifestyle. Ponzi perpetrators typically need those millions to finance their own opulent penthouses, vacation homes, and Gulfstreams.

The record-setting $50 billion scam perpetrated by Bernard Madoff has grabbed headlines around the globe, with every article explaining the trick's seeming simplicity– money from new investors is used to pay off withdrawals by the earlybirds– even as most media accounts struggle to explain how Madoff could have run his scam for decades under the watch of the Securties and Exchange Commission.

In recent days, several Ponzis have collapsed as early investors wanted to take out more money than newer investors were bringing in, a situation exacerbated by the current poor economy and tanking stock market.

If the $11 million Donnelly allegedly took seems paltry compared to Madoff's whopping haul– or even to Charlottesville's first major Ponzi, a $100 million-plus scheme conducted by Terry Dowdell– tell that to those who gave their hard-earned cash to Donnelly and are now left wondering how much, if any, they'll see again.

***

Is it simple greed that drives the perpetrators of Ponzi schemes?

"I would pick pride more than greed," says Charlottesville financial analyst David Marotta. "Pride of the lifestyle you lead and the returns you've made."

Marotta notes that the world economic tsunami has recently turned nearly every money manager into a money loser. "A lot of advisors," says Marotta, "now feel shame that they've lost money for their clients."

While honest money managers simply live with the discomfort and yearn for brighter days, shame for some, Marotta says, may be overcome by pride that "overcomes reality."

UVA Law School professor Michael Ross says Ponzi schemers are not accustomed to failure.

"The perpetrators are usually well educated, well off, with a high income net worth," says Ross. "They come from backgrounds from which one would expect legal and ethical behavior."

When things don't go well, Ross says that would-be Ponzi schemers are "unwilling to admit it to themselves or their investors, and they don't know what to do."

Six days after Madoff's sentencing and Donnelly's first court appearance, federal investigators announced that one North Carolina trader was a secret loser– to the tune of $40 million. They say that Bruce C. Kramer of Charlotte lost money every month for six years, according to the criminal complaint filed this month against his firm, Barki LLC. Yet Kramer, the complaint alleges, told the 79 investors who fueled his Maserati-bedecked lifestyle that he earned them monthly returns of three to four percent.

As worries mounted, Kramerwould carefully explain to worried investors how his operation was supposedly different from Madoff's– until he killed himself in late February.

***

Even three years after Thomas E. Coghill Jr. was sentenced to federal prison for bank and wire fraud, one of his victims, who lost $500,000 in bogus real estate deals, doesn't want his name used in the newspaper. Such is the pain and shame left in the wake of a swindler.

In the 1990s, Coghill was a developer who falsified documents to obtain loans with properties that had no equity and were often vacant lots, often in the Twin Lakes subdivision in Greene County. He left unpaid bills all over Central Virginia, according to the prosecutor, and one supplier called Coghill a "silver-tongued devil" and alleges Coghill stiffed him for $357,000.

If some Coghill creditors remained silent, others pursued charges against him, and in August 2005, Coghill pleaded guilty to two counts of fraud. The following March, he was sentenced to 30 months in prison and ordered to pay $2.8 million to Anchor Capital out of Potomac, Maryland, and $170K to First Western Investment of Charlottesville.

While indicted and ordered to refrain from financial transactions, Coghill, according to a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney's office, got involved in several more deals in Florida, including the purchase of the Conch House marina/resort in St. Augustine, which now faces foreclosure with its original owners in bankruptcy.

"You realize a lot of what y'all wrote was untrue," Coghill Jr. announces in a telephone interview, pointing out that his sentence was 30 months, not the 33 months as reported in the Hook.

Last July, Coghill, 48, was released from prison with five years of supervised release. He now lives in Virginia Beach, where his father, Thomas E. Coghill Sr., owns Investment Research Corporation.

"I had a business that was very viable," he says. "I made poor decisions with interest payments– I didn't calculate I couldn't make a profit."

Coghill concedes, however, that he's the one who put himself in this "impossible" situation.

"I made my own mistakes, and I got what I deserved," he concedes. "I had a drinking problem."

The former developer says he's now patenting beach items– he says he has a degree in physics– and doing a lot for charity in the community, including assisting the bicycle race in Virginia Beach long sponsored by his father.

"I believe I'm doing a lot of good things for the community," says Coghill, expressing remorse for the nearly $3 million of which he defrauded the owners of Anchor Capital.

"I feel bad about the money they lost, I do," says Coghill. And if things work out with his beach products or the property in Florida, he hopes to be able to repay the money.

He was less sympathetic to the local businessman who claims Coghill bilked him of $500,000– and who now operates a website called Coghill the Con.

But three days after speaking with the Hook, Coghill called back and said he does feel bad about the businessman because "he spent the last few years of his life being angry at me, and I know that doesn't make you productive," says Coghill. "I know because I spent the last few years being angry. Bottom line is, I put myself in this position."

Adds Coghill, "Now I just want to go on with my life."

"I'll never recover," declares the businessman who doesn't want his name in the Hook even though it's on his websites. In 2000, "I had nothing, just like the people with Madoff who were tied to something for years and years and then you have nothing."

This victim advises investors to turn over every stone and not make assumptions. "In Coghill's case, I was dealing with attorneys who were being scammed," he says. "I was getting legal papers I assumed were legitimate."

Thomas E. Coghill Jr. takes responsibility for the people he's convicted of defrauding and wants to pay them back.

PHOTO COURTESY THOMAS E. COGHILL JR.

And once the worst happens, take a deep breath and try to put it behind you, says the businessman. "It's very painful. It destroys relationships. It destroys trust. It destroys confidence." And while he's tried to purge this incident out of his life, he admits, "I'd love to see [Coghill] go back to prison for probation violations."

At press time, the Jacksonville Business Journal reports that Coghill has been indicted for obstruction of justice and perjury allegedly related to the real estate deals in Florida while he awaited sentencing for the Virginia charges. According to the Florida paper, Coghill calls the indictments "totally ludicrous" and is scheduled to be arraigned April 3.

At a March 12 hearing in federal court, 52-year-old Donnelly made his first public appearance. The former racer appeared fit with close-cropped dark blond hair. But wearing the thick gray stripes that is the uniform of Central Virginia Regional Jail in Orange, where he is has been held since his March 11 arrest for wire fraud, he seemed far removed from the family man who resides in the the 1500 block of Church Plains Drive near Crozet.

The federal district court in Charlottesville had already entered a temporary restraining order preventing Donnelly's companies from conducting further activities and had frozen all assets under his control. Under the gaze of Judge Waugh Crigler, the financier and former motorcycle road racer answered questions from Crigler and his attorney.

Early on, his wife appeared composed in a gray tweed jacket in the second row immediately behind the defendant, although as the hearing began, she appeared tense, her arms crossed while she repeatedly circled one foot.

"Until I talk to my husband, I can't say anything," she said when first contacted on the day of the arrest. "I need to find out more, talk to a lawyer. I want to be responsive here, but I've got a kid coming home from high school, and I have to tell him first."

After the hearing, Mrs. Donnelly declined comment, and after a private meeting with attorneys she briskly left the courthouse.

Donnelly's attorney John Davidson said that his client heads a "nice family" with two children, and that he is not at risk of flight if bond is granted.

"Mr. Donnelly is incredibly worried about his family," said Davidson. "His hope is that in this rush of accusations that have been made that people give his family the privacy they need."

Law professor Ross says that if religious or other moral foundations don't restrain a Ponzi schemer, the fallback position– as Madoff seemed to confirm during his guilty plea– is to consider "relative costs and benefits."

Ponzi schemers, Ross says, tend to overvalue the reward of making money for themselves and their investors, but to undervalue the risk of eventually getting caught and leaving a trail of destruction. Ross notes that it's not just investors but families who are often the unwitting recipients of ill-gotten gains.

For instance, Deborah Donnelly is a top fundraiser for UVA's Curry School of Education who earns a six-figure compensation package of her own, according to Foundation filings. And yet the government claims that Mrs. Donnelly may have benefited from some of the million dollars siphoned off over the last three years, as she's named in the complaint as a "relief defendant."

Her husband's attorney stresses that the designation has no criminal connotation but instead remains a civil matter that could require only that Mrs. Donnelly return any inappropriately-obtained funds.

As relatives of Albemarle's biggest Ponzi-schemer, Terry Dowdell, discovered the hard way last year, accepting treats from a criminal in the family can lead to serious charges.

***

Dubbed the Vavasseur scheme and the subject of the Hook's June 26, 2003 cover story, Dowdell's globe-spanning crime defrauded investors of over $100 million and resulted in a 15-year prison term for Dowdell, now held at Beckley Federal Correctional Institute in Beaver, West Virginia.

Dowdell's wife, Mary Dowdell, was initially seen as a mere relief defendant, who watched her house and jewels auctioned off in 2003. However, she accepted wire transfers of money from two of her husband's co-conspirators after she and her husband had already been warned by federal investigations.

She was convicted last year in the federal court and given a five-year sentence. Her daughter, Rebecca Dowdell, the comptroller for the Montessori Community School on Pantops, pled guilty and received house arrest. She did not return the Hook's call.

The Dowdell family convictions have done little to ease the suffering of victim Elizabeth Watson, a British woman whose family fortune plummeted from its unwitting connection to Albemarle County.

Watson's financial nightmare began eight years ago when she went to lunch in Leicester with a charming financier who told her she'd be investing alongside the likes of Andrew Lloyd Webber. Little did Watson know that she was handing her family fortune over to Terry Dowdell.

As court documents later revealed, Dowdell led a network of agents to gather money for non-existent investments– unless Dowdell's lavish estate in Western Albemarle counted as an investment. When it was auctioned off six years ago, the house brought $925,000. But that was little consolation for Watson, whose family is still seeking return of its money.

"We have to fight to save our house," says Watson.

Watson won one victory in Charlottesville's federal court last year when she helped persuade Judge Norman Moon to unseal some financial records. Although she despises Dowdell, she reserves her harshest scorn for the "greedy bankers" at the Halifax Bank of Scotland which offered her a loan for what should have been seen a scam.

"This was a huge bank with a big name," says Watson. "He said, 'How much do you want?' I was a lamb led to the slaughter."

Between her parents, sister, and herself, Watson's family lost two million pounds (about $4 million).

"I fell for this bag of tricks," says Watson.

In mid-February, Britain's Sir James Crosby suddenly resigned from the British equivalent of the Securities and Exchange Commission after revelations that he fired a whistleblower who tried to warn of dangerous lending practices at the Bank.

In February 2008, in a trial at Birmingham Crown Court in Leicester, England, in which prosecutors flew in Dowdell and put Watson on the stand for a week, Watson's Leicester lunchmate, Shinder Gangar, and co-conspirator Alan White were convicted of investment fraud and related charges and given seven and a half-year prison terms.

For over 15 years, Watson had run her own import/export company providing high-end house fabrics for wealthy Arab clients. Today, however, she spends most of her time heading a Dowdell victim's group called OneVoice. Her days are consumed by sending emails about efforts to pry open the books and retrieve what's left of the victims' money.

"I used to have a normal life," says Watson. "But now we have to fight so hard in this filthy, putrid stenchpot."

These days, Watson is far from alone in her suffering.

***

March 12 was a busy day in the Ponzi world. In New York, as the now-infamous Bernie Madoff was sentenced, several of Madoff's investors gathered to watch the man who destroyed their fortunes led away in handcuffs.

Charlottesville's lone Madoff investor hung up the phone when a Hook reporter called. However, Paul Allen, an 89-year-old retiree from Thousand Oaks, California, who lost his life savings, according to msnbc.com, called Madoff an "animal."

March 12 was also the day Donnelly first appeared in federal court here in Charlottesville. In addition, it was the day one of the federal agencies charging Donnelly, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, charged a Las Vegas man for running a $20 million Ponzi. Six days later, the Commission uncloaked the alleged Ponzi run by the recently deceased North Carolina man.

Perhaps no one understands better how easy it is to be sucked into a financial scam and how painful it can be than gullibility expert Dr. Stephen Greenspan. A professor of psychiatry at University of Colorado, his latest book Annals of Gulliblity: Why We Get Duped and How to Avoid It was released on December 30.

But there's a twist. On the eve of his book's publication, Greenspan learned he'd lost a large chunk of his own retirement savings in the Madoff scam.

Despite his expertise and career as a mental health professional, Greenspan found himself among the legions of the duped. And that, he says, is just more proof of what he's long argued.

"Con games are so enticing," says Greenspan, "that most people, in the right circumstances, would fall for it."

Con artists, Greenspan says, employ several tricks, but one of the most common is to operate within a trusted group of people. While Madoff had expanded to the point that some hedge funds were feeding his funds, he started with individual investors in the Jewish country club society of Palm Beach. In fact, many of Madoff's thousands of investors– now victims– were Jewish, including Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, Holocaust chronicler Steven Spielberg, and numerous Jewish charities and funds.

Donnelly, with his deep connections in the motorcycle racing world, had his own trusted circle.

***

In motorcycle racing "you tend to form real strong friendships," says John Ulrich, a champion racer and longtime editor of Roadracing World magazine, who describes a scene in which people with "real world stressful jobs" spend weekends at tracks where "they get to ride motorcycles at high speeds."

The change of pace relieves stress and also leads to intense camaraderie, particularly among those on the same team. For nearly seven years, says Ulrich, Donnelly, even before he started accepting money from his friends and teammates, raced on the "Army of Darkness" team.

"He really worked these people using the friendship angle," says Ulrich. If the charges against Donnelly are true, Ulrich says, "this guy was stealing from people, setting them up to have their money evaporate at same time he was smiling, shaking their hand, and looking them in the eye."

Donnelly made a good impresssion off the racetrack as well.

"He was very easy to work with," says Charlottesvillian Mike Ratliff, who bonded with Donnelly five years ago through their sons' interest in basketball. The pair formed a youth basketball team together with Ratliff as coach and Donnelly as manager. Donnelly, Ratliff says, was so generous that he paid paying travel expenses for team members whose families couldn't afford the cost.

Those who saw Donnelly at work say they had no reason to doubt his authenticity as an investor.

"He seemed like a very pleasant guy," said one. "He had a bunch of computers," says the person, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "It seemed like a very sophisticated operation."

Investigators were in Donnelly's office in the old C&O Station on Water Street all morning March 11 carrying material out, according to a neighbor who did not want to be identified. The office was locked, although an arrangement of fresh flowers and and motorcycle racing images covered the walls, including a cover of Racer X Illustrated.

"We'd see him riding up on his motorcycle to work," says a neighbor.

According to the complaint from the Securities and Exchange Commission, Donnelly was promising his investors stellar returns of up to 22 percent annually. However, the SEC claims, he hadn't actually invested any money since 2002.

The SEC alleges that Donnelly approached his friends in 1998 about making $5,000 and $10,000 investments in something called the Tower fund. Donnelly raised $100,000 from these efforts by assuring his investors that found ways to take short-term, market-beating positions. He hit gold in 2002, according to the complaint, when "Investor B" handed over $11.2 million.

By selling limited partnership interests in three investment funds— Tower Analysis Inc., Nasco Tang Corp., and Nadia Capital Corp.— Donnelly told investors that he would pool their funds in, among other things, stock and bond index derivatives.

Instead of investing, the government alleges, Donnelly used investor funds to repay other investors and pay himself approximately $1 million in salary and fees during the last three years. The complaint also alleges that Donnelly has been soliciting investors for a new fund called Nadia Capital Partners LP, "based on misrepresentations about his past trading results," the government contends.

Donnelly's marketing materials promised something he called "Blue Logic." The government complaint says Donnelly described Blue Logic as a "proprietary model of financial markets using algorithms derived from the quantification of a fractal wave frequency model."

If his investors couldn't understand the big words, there's evidence that Donnelly could. In 1982, Donnelly appears to have defended his UVA senior thesis in astrophysics: "Astronomical Catastrophes and the Evolution of Intelligence."

Last month, however, "Investor B" came forward, telling the SEC that Donnelly had confessed that all the monthly statements Donnelly had sent him were fictitious and that Donnelly never actually made any trades on behalf of his Tower clients.

An affadavit filed in federal court claims Donnelly admits to committing the crime– with secretly taped phone calls as evidence.

On the tapes, Donnelly allegedly admits in a phone call with an investor that he had never actually executed any trades because of his alleged inability to "push the button" on the trades due to some unspecified childhood trauma.

In a separate taped conversation with a second investor inside his Water Street office in early February, an unwitting Donnelly reportedly expresses disbelief that the first investor had not already gone to the authorities.

"The amazing (expletive) thing about [victim #2]," Donnelly said according to the redacted affidavit, "is that he didn't have me jailed right away."

Exactly one month after that conversation, Donnelly was behind bars– something his friend, Ratliff, is still having a hard time accepting.

"It's hard for me to believe he'd do anything deceitful," says Ratliff. "Hopefully, it's just mistakes he made."

***

Ratliff isn't the only Donnelly friend having a hard time believing the charges.

In a day-after-the-arrest essay published on the website of Roadracing World Magazine, editor Ulrich defends his magazine's decision to report on Donnelly's arrest– something he says sparked outrage among some readers and Donnelly friends.

"The Donnelly case is another reminder that we don't really know the people we see at the races," writes Ulrich. "Just because we see them in the paddock race after race and year after year, doesn't mean that they are honest."

There was no shortage of cameradie around race tracks, as this poem at the now-removed armyofdarkness.com relates:

There once was a team called the Army,

Whose members were all somewhat barmey.

The first crasher was Jim,

Then Sam followed him;

Thought John, "The next crash will harm me"–Bobby Jones

"As long as nobody tried to take out too much, too fast," Ulrich writes, "the scheme hummed along."

Until it didn't.

***

How can an investor know if they're dealing with a scam artist?

"If it seems to good to be true, it is," says U.S. public defender Fred Heblich, who defended convicted Ponzi artist Dowdell back in 2003 when Heblich was in private practice. Heblich's talking about the promises of very high returns with low risk investments made by Ponzi schemers and other nefarious financial criminals.

Should investors simply have been concerned by Donnelly's year after year double-digit returns? Is such investing success impossible?

Stewart Darrell, a portfolio manager with Charlottesville-based Darrell & King Investment Counsel, says no. In 2007, Money Manager Review ranked his firm the top "balanced money manager" for their double digit returns over seven years. In fact, he says, his firm has averaged double digit returns over the last 33 years.

Another double-digit earner: Jaffray Woodriff, the head of Quanititative Investment Management, the second largest hedge fund in the southeast United States which just happens to be located in downtown Charlottesville.

Since 2001, Woodriff has seen the money he manages balloon from $700,000 to $3 billion, with net annual returns averaging 20 percent. In 2005, QIM made headlines for topping 32 percent, and the firm now has 25 employees.

Sitting in his office in the 400 block of East Market Street, the tall and lanky investor with shaggy brown hair appears 10 years younger than his actual age, 39. Adding to Woodriff's boy wonder investor air are more than half a dozen large computer monitors that line two walls of his spacious office– several displaying colorful graphs and data so complicated to the untrained eye that they might as well be abstract art– or ground control for a NASA trip to Mars.

The 1991 UVA grad calls his investment style "quantitative behavioral finance," which uses mathematical models to predict the collective behavior of the market.

Just because it's too complicated for many people to understand, says Woodriff, who cofounded QIM with a college pal, Michael Geismar, there are plenty of ways his clients are assured that their money is safe– or as safe as anyone's money can be in an authentic investment.

Darrell says transparency is key, and that his firm's use of third party brokerage accounts– such as Charles Schwab or Merrill Lynch– provide proof that money is actually where his clients believe it to be.

Woodriff's firm operates in a similar way. Most of the money invested with QIM is not directly controlled by QIM– clients choose their own unaffiliated brokerage firm to invest in the program. Madoff, however, forced his clients to rely on his own broker– Madoff Securities– in order to keep tight secrecy.

"That shouldn't ever have been legal," says Woodriff, who blames the SEC for failing to uncover the Madoff scandal despite numerous alerts over 10 years.

"They could not have been better tipped off about the fact that he was running a Ponzi scheme," says Woodriff. "Either they're astonishingly inept, or they're corrupt."

But while his own firm's transparency and oversight by not only the SEC but also the Commodity and Futures Trading Commission and the National Futures Association satisfies most of his sophisticated investors, Woodriff says one would-be investor– who'd been burned by Madoff– was made nervous by QIM's stellar returns.

"He must have said seven times to me, 'I wish your track record weren't so good.' It became a running joke," Woodriff recalls.

There are other differences between a whiz investor like Woodriff and a charlatan. Woodriff is glad to consider any new client who meets the financial requirements typical in the world of hedge funds: a $1 million minimum investment, and only individuals of extensive net worth are permitted to engage in what the SEC considers high risk investing.

While that type of exclusivity protects investors of moderate means from losing money they can't afford to invest, Ponzi schemers prey on the allure of exclusivity as a way to reel in their victims.

***

"Donnelly didn't pitch people," Ulrich writes in his essay. "He didn't tell potential investors that he based his trading theories on astrophysics or weird theories. Instead, Donnelly hinted that he wasn't accepting any new investors and let his friends and associates talk about how well things were working out; the scheme grew from there."

Ulrich writes that one racer's sister left her money in the fund instead of paying off an auto loan because Donnelly was allegedly paying a higher interest rate. Others put in sums of $5,000 or $10,000 after hearing "paddock tales" of high returns, Ulrich writes.

Such tales, psychiatrist Greenspan notes, are another typical tool of the scam artist: let others do the scammers' marketing for him. By allowing gossip of stellar returns to circulate on the Palm Beach social circuit, Madoff managed to imbue an air of exclusivity just as Donnelly allegedly didn't stop the so-called paddock tales.

"You want the victim," says Greenspan, "to basically beg you to take his money."

Donnelly, who remains behind bars, returned to federal court on Thursday, March 19 to waive his right to a preliminary hearing and delay his request for bond.

The very nature of his alleged crime, however, puts Donnelly in something of a Catch-22. Although he is innocent until proven guilty, and although he has not yet been formally indicted on the charges, his assets have been frozen until the courts can establish if any of them were obtained fraudulently.

"This man should be home with his children," says Davidson, declining comment on the complications of gaining bond when one's assets are frozen.

For Ulrich, who did not invest with Donnelly, watching his friends grapple with the sudden loss of their life savings is painful, and he says he believes anyone could have been victimized– even those who claim they're too smart.

"It was more complex than people just being stupid," says Ulrich. "This guy worked it for all it was worth."

–with additional reporting by Dave McNair, Lisa Provence, Lindsay Barnes, and Hawes Spencer

Donnelly, pictured here at a race in 1999, spent years developing friendships with his motorcycle racing teammates before allegedly beginning to take their money.

PHOTO BY BRIAN J. NELSON

Over the course of one month before his arrest, the FBI secretly taped conversations between Donnelly and his "investors" in which Donnelly admitted he'd never actually executed trades on his investors' behalf.

PHOTO BY BRIAN J. NELSON

In 2003, Terry L. Dowdell was convicted of conducting a $100 million-plus Ponzi scheme. He is currently serving a 15-year sentence in federal prison and is due for release in 2017. His wife and daughter were also convicted of lesser charges.

FILE PHOTO

Donnelly's attorney John Davidson speaks outside the federal courthouse after Donnelly's initial hearing on March 12.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Quantitative Investment Management co-founder Jaffrey Woodriff blames the SEC for failing to uncover the Madoff scandal after repeated warnings. "They could not have been better tipped off about the fact that he was running a Ponzi scheme," says Woodriff, who has seen the money he oversees grow from $700,000 to more than $3 billion in the last eight years, making QIM the second largest hedge fund in the southeast.

PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

Donnelly's Tower Analysis office is located in the 400 block of East Water Street downtown.

PHOTO BY LISA PROVENCE

#