COVER- What a Waste: Is the trash Authority going obsolete?

"The landfill of the future just came to town," says Peter Van der Linde, who recently opened a $11 million recycling facility near Zion Crossroad that could solve our waste woes. But first he'll have to battle our own Waste Authority, which is suing him for $3.5 million.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Why is the main local trash authority suing the man who has offered a solution for the local waste disposal problem? And why is that man paying investigators to find out what words are spoken at the entrance booth of the authority's favorite trash station?

It's all part of an ongoing waste war. And before it ends, there's a chance that the private citizen– unless he's vanquished in court– may have beaten government at its own game.

Before you toss this newspaper in the recycling bin (we hope that's what you'll do after reading it), let's talk trash with Peter Van der Linde.

A 'real player'

"The landfill of the future just came to town," says Van der Linde, a slender, soft-spoken man whose voice sounds not unlike a friendly wizard in a fantasy film, but although it might seem like magic, his new $11 million recycling facility near Zion Crossroads isn't imaginary. It really does turn trash into cash.

"In the last seven years or so, these separation machines have really been perfected," says Van der Linde. "I did a lot of research on them, and I believe this one I bought is the ultimate machine."

Inside a 100,000-square foot steel-framed building, one of three such structures on the site, a 15-man crew is running a state-of the-art recycling machine, a $3.2 million device that can sort up to 100 tons of construction and demolition debris and curbside recyclables per hour.

Located adjacent to the publicly supported trash transfer station on the same road, Van der Linde's operation lies so close to the competing station that any trucks on their way to one have to pass within mere yards of the other. The two facilities may be neighbors-in-trash, but according to Van der Linde, the similarity ends there.

While the publicly-assisted station sends its trash to a Richmond-area landfill and its recyclables to a sorting center in Chester, Van der Linde says he processes nearly everything he gets right on site.

The high-tech device was manufactured by a Canadian company called Sherbrooke OEM, and according to manager Jeremie Bourgeois, Sherbrooke has sold hundreds of sorting machines– but none quite like the one that landed in Zion Crossroads.

"Peter's is the biggest design we've sold," says Bourgeois. "He's a real player now."

Now that's a MuRF

The new operation that gives Van der Linde such pride is called a "materials recycling facility"– or "MuRF" as it's known in the industry. MuRFs have actually been around for decades, but during the 1990s, as states and local governments began ramping up their recycling efforts, their numbers began to increase.

But Van der Linde says his fancy machine was the missing link, as hand-sorting and earlier-generation machines have been wildly inefficient. (And he notes there's a lot of worker turnover, especially at "dirty MuRFs," the facilities that process household trash, where the task involves hours of picking waste on a conveyer belt.)

Like a mechanical prospector, Van der Linde's recycling machine has multiple levels of vibrating conveyers to separate various materials (with the help of some hand-sorting) and feed them into a system that includes a giant electromagnet to extract metal, a "trommel" that uses centrifugal force to extract smaller materials, a "destoner" to separate light and heavy things, a "star screen" to separate soft and hard objects, and an array of other gadgets.

Along the way, the machine will deposit concrete, metal, cardboard, paper, plastic, wood, carpet (including pad), glass, metals, brick, yard waste, drywall, asphalt, styrofoam– and nearly everything else imaginable– into separate bins. "Everything on the planet except household waste," says Van der Linde, "but that's coming soon."

Van der Linde says his facility is able to sort and recover 90 percent of what comes in for resale to secondary markets. He stays tight-lipped about who buys the salvaged materials, but since he's charging haulers to drop off their waste and charging buyers to purchase the sorted extracts, it's clear he's found a business model with revenue streams on both sides of the deal.

Van der Linde has been immersed in refuse for most of his life. As a child of the 60s, he recalls riding in cars (without a seat-belt) and tossing garbage out the window without a second thought. Instead of college, he joined the Merchant Marines, eventually rising to the rank of captain of a supertanker that spewed garbage across the seven seas.

When he moved to Charlottesville and got into the home-building business, he saw all the trash that industry produces and eventually founded a side-business in dumpsters. Today, he owns 801 dumpsters, making his the biggest such company in the area. It was while constantly paying to dump those containers and knowing that most of their contents were going into some landfill somewhere that Van der Linde's trash conscience awakened and he had an idea– to build a MuRF of his own.

"I always thought somebody would figure this waste problem out," says the now 59-year-old entrepreneur. "I just didn't think it would be me."

Since it went online in December, he says, the machine is already handling 250 tons a day, or 7,500 tons per month. And that's a volume that may already be striking terror into the heart of local governments.

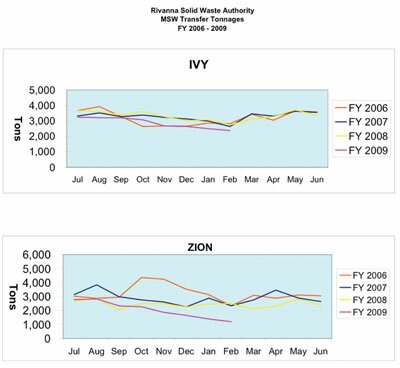

According to a chart recently released by the official government waste body, the Rivanna Solid Waste Authority, its biggest recent month was October 2006. That's when the Authority logged nearly 4,500 tons of household waste at the Zion Crossroads facility and a bit under 3,000 tons at its site in Ivy. In other words, Van der Linde appears to be doing as much as the Authority's two facilities combined when the economy was humming.

Van der Linde points out that the survival of his business over the long term will depend on volume, on convincing trash haulers to use his facility and pay his tipping fees. For now, he appears to have an edge because he charges a tipping fee of just $44 per ton, $18 less than the Authority-favored transfer station right next door, and $22 less than Ivy.

And, he suspects, that's what got him sued. But how did it get to that point?

No more dumping in Ivy

For more than 30 years, trash in Charlottesville and Albemarle meant one thing: the dump in Ivy. But after a lawsuit and community pressure, the Authority closed the Ivy Landfill in 2001. Not only did that decision leave behind a big mess– as the early trash cells were unlined– but it will also cost the City, County, and UVA (under a shared agreement) $13.3 million over the next 10 years to clean up and contain the toxic aspects of the site. In addition, the Department of Environmental Quality has mandated that groundwater monitoring continue for the next 50 years, at a cost the Authority has yet to estimate.

The closing converted the Ivy Landfill to transfer-station status as it was redubbed the Materials Utilization Center. Although the Authority could still charge tipping fees, it had to pay out much of that money to actual landfills and commercial trash haulers, a situation that makes the Authority financially dependent on taxpayers.

For instance, the Authority's most recent budget shows it expects to receive about a million from the County, half a million from the City, nearly $200,000 from the University of Virginia, and over two million from its own reserves this year. And yet recently released figures show revenues trailing projections by up to 25 percent with an operating loss of over $1.2 million and its reserves slipping to $5.3 million at the end of February.

To create a revenue stream, the Authority has come up with the idea of charging area trash haulers, as well as the City, a $16 per ton "service contribution fee" to use the Zion Crossroads transfer station, a fee that Allied, which owns the station, would be exempt from paying. And there's the rub.

"We use the RSWA facilities as little as possible," says Ken Bahr, owner of Cavalier Container, a local dumpster rental business, "because they tacked on that $16 service fee."

Essentially, the Authority now makes money not by directly accepting trash, but by charging this fee for what it calls "comprehensive waste management services." The Authority writes contracts, recycles, monitors the Ivy site, and educates the public. But it no longer actually moves any trash.

And the haulers seem to know this.

"In exchange for that money, they do nothing," says Bahr. "They don't even touch the garbage. I really have a problem with that."

Apparently, Charlottesville's government has a problem with that, too. The City withheld nearly $2 million in fees allegedly owed to the Authority and sought an alternative agreement since the fee system went into effect. The Authority argued that the fee system is a way for the city to share its responsibility for keeping the Authority afloat, even if the citizens no longer actually use its services.

In 2007, then Charlottesville mayor David Brown said the fee system was "unfair" when delivering a City's check for $400,000 in unpaid service fees to the Authority.

Bahr found a simple way around the fee; he now sends nearly all his trash to Van der Linde, even though the two are friendly competitors in the container business.

"I used to send the RSWA $10,000 to $15,000 a month," says Bahr. "Now I send them barely anything at all. And that's fine with me."

Bahr isn't the only person upset with the Authority. The fees so riled one hauler that he filed a federal lawsuit against the Authority. His name was Peter van der Linde.

In 2005, he alleged that the fee system gave Allied an unfair advantage over all the smaller, local competitors. Van der Linde ended up losing the lawsuit, though not because U.S. District Court Judge Norman Moon thought the fee system wasn't questionable, but because he believed that Authority policy should have been challenged through the political process. Instead of playing politics, however, Van der Linde decided to challenge the Authority at its own game.

"Peter's business," Bahr notes, "is already sucking millions of dollars away from the RSWA."

In the end, the Authority could be wishing it never riled Van der Linde.

Private haulers do it

In Albemarle County, which does not offer public trash pick-up, many– if not most– private haulers are already on to Van der Linde.

"It's fantastic what he's doing, because for anyone who chooses to use this service, it will now be effortless to recycle," says Alec Cargile, president of Lithic Construction. "Our lives just got a lot easier."

Another company, Time Disposal Inc., has also stopped using the publicly-assisted transfer station in favor of Van der Linde's facility, both to avoid the more expensive tipping fees and to complement his company's own curbside recycling program, says company marketing director Gene Ware.

"We wanted to make sure that things were really getting recycled," adds Ware, recalling an era in which supposed recycleables, when not perfectly sorted, often found their way into landfills.

As Van der Linde points out, although the city's curbside recyclables are taken to his Allied neighbor, the facility has no proper sorting capacity. Indeed, one afternoon, a reporter watched Allied and Waste Management trucks dumping their loads in a building a third of the size of Van der Linde's facility, with no sophisticated sorting machinery in sight.

After years of being conditioned to think of recycling as a social responsibility, perhaps involving a drive to the McIntire Recycling Center with sorted cans and bottles, or making sure a curbside bin–- as the City uses for certain easily-recycled materials–- doesn't contain forbidden materials, the Van der Linde way can be difficult for some to grasp.

Everything really can go in one bin.

"Our biggest challenge, strangely enough, is communicating the simplicity of what we do here," says Van der Linde. "You dump your trash here. The only difference between us and a landfill is we dig through it with fancy, expensive machines and recover and reuse 90 percent of it."

Where does this leave the Authority?

In December 2007, Van der Linde says he contacted Authority director Tom Frederick and board chair Mike Gaffney with an offer to lend his containers to the Authority for free and process recyclables for "half the price" it would cost the Authority to do it itself.

Earlier that year, Frederick had announced that the Authority was considering making the public pay for recycling services because the task was becoming so expensive. Indeed, in the current fiscal year, the Authority expects to spend over $669,256 on its recycling operations with just $365,000 in revenue.

Van der Linde says his proposal was met with silence. Despite additional attempts to contact Gaffney and Frederick, Van der Linde says he has yet to receive a response from either man.

Actually, he did hear from them, in a way, about a month later– when the Authority filed a $3.5 million lawsuit against him.

Costly solution?

Specifically, Van der Linde offered to place his containers at the McIntire Recycling Center, the crown jewel of the Authority's recycling efforts, which he believes has become an outdated model.

"It's a costly, staffed, single-collection facility that requires users, at great effort, to separate their recyclables into many different containers and often travel a great distance, to a single recycling location with limited receiving hours," says Van der Linde.

Today, Van der Linde, despite the legal battles, insists he hasn't been intentionally trying to put the Authority out of business. It was bigger than that, he says.

"It's a wonderful thing– its called progress," he says. "This is simply a better mouse trap."

Van der Linde acknowledges that his is no miracle operation, as his recycling machine still requires some hand-sorting. Also, the sale of recyclables is an emerging market subject to market swings, and his facility has yet to be tested over the long haul, but he's convinced that this is the future of waste.

"We are in the starting blocks poised to divert all garbage away from landfills and redirect it back into the mainstream, not the waste-stream," he says.

The Authority appears to have been on the sidelines. In a recent email to a real estate blog, County Supervisor Ann Mallek blasted the pace of the Authority's efforts just to release a strategic plan.

"We have been treading water," wrote Mallek. "I will again push our staff to come forth with the solid waste study, last year's hold up, so the community can read for itself the results of all the public meetings and surveys."

While the government waits for a plan, which is scheduled to be completed by early May, Authority director Frederick insists that partnering with private enterprise has always been a consideration. Yet a draft plan included reviewing the feasibility of building, at taxpayer expense, a $7- to $10-million MuRF.

In defense of a public facility, Frederick points out that the goal would be to get enough commingled recyclables from City, County, and UVA that it would generate sufficient revenue through the sale of recycled products that no tax support or tipping fees would be needed.

However, Frederick admits that no plan, timetable, or commitment has been made. As for Van der Linde, Frederick appears in no rush to embrace a partnership.

"If the County or City want the RSWA to provide additional services in the future that could be delivered to his facility," says Frederick, "then Mr. Van der Linde could then submit a public bid in response to a request for proposal for the service."

Authority board member Mark Graham, who is also Albemarle County's planning director, admits to some worry about Van der Linde's operation taking business away because, he says, "we depend on volume for our revenue."

Teri Kent, a member of the Authority's citizens advisory board, says she'd love to see local government come together in such a "sustainable-minded community" with Van der Linde.

"My optimistic tendency wonders," she says, "if we could get the RSWA board, city and county officials, and Van der Linde in a room. Myself and Mayor Norris could moderate and see what we could come up with."

It now appears, however, that the only room in which the Authority and Van der Linde will be meeting is a court room.

The lawsuit

In January 2008, the Authority filed its $3.5 million lawsuit against Van der Linde, accusing him of fraud and conspiracy in an effort avoid paying the Authority's $16 per ton fee. Between 2005 and 2007, the suit says, before opening his recycling center, Van der Linde allegedly got his haulers to lie about the source of their trash when dropping loads in Zion Crossroads.

If recycling advocates had hopes of a public-private partnership between the big boys, those hopes may have been dashed, as Van der Linde has fired back with a demurrer claiming there is no basis for the suit.

Remarkably, the suit seems to have flown under some official radars, as neither the Authority citizens advisory board member Kent nor her colleague and chairman Jeff Greer knew anything about it. Nor did the first four public officials the Hook contacted for comment: Charlottesville Mayor Dave Norris, fellow Charlottesville City Councilor Holly Edwards, as well as County Supervisors Anne Mallek and Sally Thomas.

"Wow, I feel very uninformed," said Mallek after learning about the lawsuit. "I'm embarrassed about that."

"That's red flag number one," says former City Councilor Kevin Lynch, "that the mayor of Charlottesville doesn't know about this lawsuit."

Lynch has recently been critical of the Authority's sister board which runs the local waterworks (they share 4/5 of the membership), which tried to create a massive new reservoir that could cost over $200 million– a plan which Lynch contends was based on misleading information about alternatives such as dredging the existing reservoir.

"They act with no accountability," says Lynch. "They are like a private business, joined at the hip with the public purse."

Frederick, who is also the mastermind of the controversial reservoir plan, refused to comment on the lawsuit against Van der Linde and his companies, but Authority board member Gary O'Connell did.

"It's a business deal," said O'Connell. "They owe money."

As for why the Authority failed to notify the boards that appointed it, chairman Gaffney answered, "I don't speak to the supervisors, and I don't speak to the councilors."

"We're working on getting better city representation on the RSWA board," says Mayor Norris, referring to a March 16 Council meeting during which councilors approved a resolution to add one Councilor and one Albemarle County Supervisor to the Board, "which could help solve alot of these problems."

An incentive to lie

Since the lawsuit filing, Van der Linde says he feels considerably less charitable to the Authority. In fact, he calls the lawsuit a "vendetta" and derides the Authority as "hopelessly, blatantly, out of control."

Prepared by Jonathan Blank of the McGuireWoods law firm, the suit notes that employees at Allied, the actual owner of the Authority-favored trash transfer facility, are instructed to ask all haulers entering the Zion Crossroads facility where their trash is coming from to determine if the hauler should be charged the Authority's $16 per ton service fee. The filing provides no specific evidence that Van der Linde's drivers lied, nor does it specify any dates when the alleged incidents occurred.

The defense, however, is rich with detail. Shortly after the suit was filed, Van der Linde says, he hired a private investigator to install audio/visual equipment on his property adjacent to the Allied tipping station. The investigator recorded hours of footage documenting, he says, that Allied "almost never" asked drivers about any trash's origin, evidence that Van der Linde says he recently hand-delivered to the offices of Gaffney and Frederick.

"There are hundreds of haulers going there," says Van der Linde. "I'm the only hauler that has been sued. Why?"

When asked the same question, Authority director Frederick and legal council Kurt J. Krueger declined comment. In a twist, Van der Linde points out that there's actually a hefty incentive for him to tell the truth about his trash. His companies would have to pay an additional $18 per ton, according to the facility's rates, when bringing trash from beyond Albemarle's borders. In other words, the lawsuit seems to allege, Van der Linde has been lying to pay more.

Moreover, Van der Linde says that Allied has a powerful reason not to ask the burning question. That's because one ton of in-district trash earns Allied a regulated fee of just $46, while Allied can earn $80 per ton of non-district trash.

"There's actually a $34 per ton financial incentive for Allied not to ask where the trash is coming from," Van der Linde explains, "as they make less per ton when it's coming from the City or the County."

"They're also assuming that I could convince my 52 employees to lie with unanimity over those years, not to mention the fact that it would have cost me a fortune to make them do so," he says. "It's incomprehensible."

Garbage-ola

In two months, Van der Linde says that he'll quietly cut a ribbon on a new $600,000 machine that can sort through household garbage– everything from baby diapers to worn-out furniture to egg shells.

He'll be charging haulers a $50 per ton tipping fee. That's four dollars more than he charges to empty construction containers but still $12 less than the Authority-sponsored transfer station at Zion Crossroads charges for accepting household waste, and $15 less than the Authority charges at its own transfer station in Ivy.

And again, instead of trash moving to a landfill, it's the end of the line for most trash finding its way to Van der Linde, as the garbage will be sorted and recycled on site, with about a 60 percent recovery rate, Van der Linde estimates.

"When that machine is up and running, then we'll finally be able to take nearly everything on the planet," he says.

Remarkably, almost nothing about Van der Linde's operation has appeared in the local media. Even local government waste officials are just beginning to catch wind of it.

Steve Lawson, the City's public services manager, said he'd only heard of the upcoming household garbage operation "a few days ago" when a reporter called. Within a few more days, Lawson was part of a City delegation that received a tour.

"Everybody was impressed," Lawson said afterwards. "Right now, we have two collection contracts, but we could potentially have one," says Lawson. "We need to take a look at that."

End of the line?

Repeated messages left with area executives with Allied, now merged with Republic Services, went unreturned. That left the Hook unable to obtain data for the fall-off in traffic since Van der Linde opened next door. But a pair of charts released at the Authority's recent board meeting show the numbers falling.

Since closing the Ivy Landfill, it's clear the Authority has been struggling financially. But has it now become obsolete? How long can its $5.3 million reserves last?

At its March 23 meeting, the Authority board declined to answer a reporter's question about its economic viability. But if Van der Linde's operation takes off the way he hopes it will (and the way many recycling fans hope it will), it might be too late for the Authority to partner with him. With a sizeable head start on construction and demo debris and recyclables, and garbage soon in the offing, why would Van der Linde need the Authority?

"I think the answer to your question," says Authority citizens advisory board chair Jeff Greer, "is that he wouldn't."

Frederick defends the Authority's services by pointing out that the Ivy and Allied transfer stations currently accept garbage, while Van der Linde's facility does not, although he well knows that advantage will soon come to an end as the entrepreneur's opens his new household waste facility.

Ironically, by the time the Authority brings Van der Linde to court to retrieve the tipping fees it claims it's owed, which the recycler thinks will be next spring, the Authority could be looking at even more red ink on its books.

City Councilor Brown, who was the only elected official the Hook found who knew about Van der Linde's operation and the Authority lawsuit, says he hopes Van der Linde is successful, and that the two sides can partner after the litigation ends.

"They aren't starting off in a real good place," says Brown. "But after that's over, I hope we can move on and find out what's best for the county and the city."

The amount of garbage the Authority can tax is plummeting, even though Van der Linde won't do garbage for another month or so.

RSWA GRAPHIC

"In the last seven years or so, these separation machines have really been perfected," says Van der Linde of his new $3.2 million recycling machine.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Tom Frederick, left, directs the Rivanna Solid Waste Authority while Kurt Krueger, right, serves as legal counsel. The five members of the board are Judy Mueller, Gary O'Connell, Mike Gaffney, Bob Tucker, and Mark Graham. (Except for Graham, this is the same team that runs the Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority.)

FILE PHOTOS BY HAWES SPENCER

Everything really can go in one bin. "Our biggest challenge, strangely enough, is communicating the simplicity of what we do here," says Van der Linde. "You dump your trash here. The only difference between us and a landfill is we dig through it with fancy, expensive machines and recover and reuse 90 percent of it."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Steve Lawson, head of Charlottesville's public service, says he was "impressed" after touring Van der Linde's recycling facility. "Right now, we have two collection contracts, but we could potentially have one," says Lawson, referring to Van der Linde's operation. "We need to take a look at that."

FILE PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Building contractors have used Van der Linde's Container Rentals for years, but now he's re-branded his business as Van der Linde Recycling.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

#