COVER STORY- Undaunted mystery: New push for answers 200 years after death of Meriwether Lewis

"I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprise to him," Thomas Jefferson wrote of his neighbor, friend, and former aide before the exploration. After Lewis died, Jefferson wrote, "He did the deed that plunged his friends into afflictions and deprived his country of one of her most valued citizens.

"I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprise to him," Thomas Jefferson wrote of his neighbor, friend, and former aide before the exploration. After Lewis died, Jefferson wrote, "He did the deed that plunged his friends into afflictions and deprived his country of one of her most valued citizens.Charles B.J.F. de Saint Memin pastel photo Missouri Historical Society

bust photo Michaele White, Virginia Governor's Office.

stamp U.S. Postal Service

Buried alone in a small park located 75 miles southwest of Nashville is the body of Meriwether Lewis, a Charlottesville-area native and leader of the fabled Lewis and Clark expedition. His remains could answer a question that has vexed scientists and historians and has been considered one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in American history: How did he die?

"It's the ultimate cold case," says Howell Bowen, Lewis' great-great-great-great nephew who lives in Albemarle County.

Bowen and other Lewis descendants have taken up the case, and after being denied the opportunity to exhume the explorer's body for more than a decade by the National Park Service, a new push may be a breakthrough in the search for answers 200 years in the making.

A Hero's Return

Following a nearly two-and-a-half year expedition that became their claim to fame, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark returned to St. Louis, Missouri in September 1806 heralded as national heroes.

"It was a series of celebrations that took until just about Christmas," says Daniel Thorp, an associate professor at Virginia Tech who has studied the expedition for the past two decades. "Every town they stopped in had a banquet for them."

The expedition received top billing in newspapers– and not just in the new republic. "It got around the world," says Thorp.

For Lewis and Clark and their Corps of Discovery, the trip had been a rousing success. Exploring approximately 8,000 miles through the newly purchased Louisiana Territory and on to the Pacific coast, the 33-member party brought back a stockpile of information about the terrain, wildlife, and native tribes located along the western frontier, sustaining only one casualty (most likely due to appendicitis) on the entire trip.

"It really helped precipitate expansion into the Missouri Valley region," Thorp says.

Lewis and Clark reported to Thomas Jefferson, whom Lewis once served as personal secretary, and when the expedition was complete, President Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory– a position which would send him back to St. Louis.

Governor's job

Two hundred years after their journey, Lewis and Clark were a rousing success once again, their fame buoyed by Undaunted Courage, the 1996 biography by Stephen Ambrose. Yet Lewis entered the governorship in 1807 with many pressing problems.

The large geographical area– 828,800 square miles– was full of feuds between rival parties and factions. The area was also rocked in the wake of treason allegations levied against Aaron Burr, in a possible plot to invade Spanish territory including Mexico, which at the time held two-thirds of the world's silver resources.

"He was hailed as a conquering hero," says Thorp. "Now he was being asked to be a bureaucrat."

Lewis even had trouble with his Lieutenant Governor, Frederick Bates, who frequently spoke out against him during his time in office. In addition, Lewis was pressed to condense his expedition journals so that they would be ready to print.

"These were massive journals," explains Thorp. "There was no way for all of that to be published."

Adding to the swirl of problems is speculation that Lewis may have had an addiction to alcohol or medicines, and he had trouble forming romantic relationships.

"He never had a happy relationship with a women," says Thorp. "Clark had gotten married a few years before, and Lewis professed being very jealous."

Despite his difficulties, Lewis was able to find some successes during his time in office. He founded a Masonic lodge as well as the area's first newspaper; and he had the territory laws printed in both English and French, at his own expense. The largest difficulties for Lewis were financial.

His money woes culminated around the middle of 1809 when nearly $2,500 he was expecting in reimbursements from the federal government were denied (a large amount considering his annual wage was $2,000). One denial cost Lewis $940 for the transportation of a Mandan Indian chief to his homeland, which had been promised by the federal government under Jefferson, and another rejected request cost Lewis $1,517.95, money he had spent to print 350 copies of the territory's laws.

It was at this point that Lewis decided to travel to Washington in order to secure payment in person. With plans to return that December, Lewis left St. Louis by boat on September 4, 1809.

Accompanied by his servant John Pernier and his dog Seaman, Lewis traveled down the Mississippi River, stopping in what is now New Madrid, Missouri to recover from fever brought on by what might have been malaria. While in New Madrid, Lewis wrote a will leaving everything to his mother, which was signed, dated, and witnessed September 11. Returning onward, with New Orleans as his next intended transfer point, Lewis stopped instead at Fort Pickering, located at what is now Memphis, on September 15.

Lewis, the commander would later say, arrived in a "state of derangement." The following day, he penned a letter assuring President Madison that his health was on the mend and that he was switching to an overland course to Washington to avoid any encounters with the British. The letter, although just seven sentences long, contains over a dozen amendments and strike-throughs, enough changes to lend support to theories that his mind still needed plenty of healing.

Lewis stayed at the fort for just under two weeks, and when he resumed his voyage, he indeed changed course to an Indian trail and then to a buffalo track turned thoroughfare spanning the nearly 500 miles from the Mississippi town of Natchez to Nashville, the Natchez Trace.

After crossing the Tennessee River on the Trace, Lewis and his party took up lodging at Grinder's Stand, a small inn located near what is now known as Hohenwald, Tennessee, on the evening of October 10, 1809.

The following morning Meriwether Lewis would be found dead at the age of 35. The events of that night left many unanswered questions, even to this day.

What happened at Grinder's Stand?

While many people immediately believed it was suicide, the confusion stemming from the events of that night comes as a result of no eyewitnesses of the incident and only few partial witnesses: Priscilla Grinder, proprietor of the inn, her servants, and John Pernier, Lewis' free black servant.

James Neelly, agent to the Chickasaw Nation, was supposed to be traveling from Fort Pickering with Lewis, but Neelly had sent Lewis, Pernier, and another servant ahead while searching for two of their horses that had strayed. It was Neelly who first reported the death in a letter to Thomas Jefferson dated October 18.

"It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis, Governor of upper Louisiana who died on the morning of the 11th Instant and I am sorry to say by suicide," Neelly wrote.

Captain Gilbert Russell, commander of Fort Pickering, allegedly summarized Lewis' death in gruesome detail in an unsigned statement dated two years later, 26 November 1811. According to this statement, Lewis first shot himself in the head, and when that bullet did not penetrate his skull, he shot another bullet through his body, with the bullet coming "down low through his back bone."

Lewis, still alive after the two gunshots, then allegedly proceeded to request water from the terrified Mrs. Grinder, who lay in silence in her own bedroom. Lewis would then allegedly find his razors, and a servant of the Inn would find him "busily engaged in cutting himself from head to foot." Lewis allegedly declared that he had killed himself "to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honor of doing it."

Upon hearing the news, William Clark, Lewis' partner on the expedition, seemed convinced that his good friend's death was a suicide, writing in a letter to his brother, "I fear the waight of his mind has over come him, what will be the consequence?"

Thomas Jefferson, who assigned Lewis on the expedition and lived with him in the White House for a year, also contended that Lewis "did the deed."

A journal entry from Lewis on his 31st birthday– four years earlier when he was still on the expedition– is commonly cited by suicide believers.

"I reflected that I had yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the happiness of the human, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation," Lewis wrote. "I viewed with regret the many hours I have spent in indolence, and now soarly feel the want of that information which those hours would have given me had they been judiciously expended."

More disturbing are reports of Lewis' condition upon arriving at Fort Pickering. Under close watch of his boat's crew after two alleged suicide attempts while on the trip, one that came very close to succeeding, Russell's statement hints that Lewis' "state of derangement" stemmed from excessive drinking.

Recovering his senses in about six days, Lewis waited another six to eight days, expecting Russell to travel with him to Washington– which did not happen after Russell's request for leave was denied– before leaving instead with Neelly.

Despite what the innkeeper and her servants allegedly said, other evidence has raised the possibility of murder. Most noteworthy was the exhumation of Lewis' body that occurred in 1848, as government officials, in the creation of a monument for him, looked to determine whether or not the body at Grinder's Stand belonged to Lewis.

The Lewis Monument Committee, which examined the remains, wrote that they believed Lewis had died "by the hands of an assassin." Unfortunately for researchers today, no explanation was given for that conclusion.

Also weighing in the discussion is the weapon used. According to contemporary accounts, Lewis carried a pair of .69-caliber 1799 North and Cheney pistols, making them an incredibly powerful weapon and one unlikely to fail to kill at close range.

"A .69-caliber is the cannon of handguns," says James E. Starrs, a forensic expert appointed by the family. "You gotta be kidding me that someone would survive that long from that type of shooting," says Starrs. "It would literally take the head off."

For Kira Gale, who has researched the expedition and co-authored with Starrs The Death of Meriwether Lewis: A Historic Crime Scene Investigation, a determination of suicide could be detrimental to Lewis' legacy. "It's a very bad message to send to children or to adults that somebody of his caliber and talent would commit suicide," says Gale.

In the new book, Gale proposes that General James Wilkinson, who preceded Lewis as governor of the Louisiana Territory but was removed for abuses of power, murdered Lewis, and that accounts of his death, including that by Fort Pickering's Russell, were forged by Wilkinson or his clerk in order to create the appearance of suicide. Wilkinson, who testified against Burr at his treason trial, was long suspected of being a paid informant to the Spanish. Indeed, this was finally proven after his death, when a historian named Charles Gayarré published Wilkinson's letters to Rodríguez Miró, the Spanish governor of Louisiana.

"I don't think he was depressed," says Gale. "I think he was murdered."

Some claim that the monument committee may have simply been attempting to protect Lewis reputation when it rejected the suicide theory. Starrs, however, says that he wouldn't mind learning that Lewis' death was in fact a suicide.

"If it's a homicide, the next question people ask is ‘Who did it?'" Starrs says. "That's not my job."

Starrs also noted that it wouldn't be completely unlikely for Lewis' suicide to be a result of illness or the drugs used to treat them. In 1994, an epidemiologist suggested that Lewis might have been in the last horrific stages of brain-destroying syphillis.

"We'll be able to find out from the bones," Starrs says.

For their part, the Lewis descendants, many of whom still reside around Charlottesville, have insisted that they don't have a stake in either theory of their ancestor's death. Many family members would like to give Lewis a Christian burial, with military honors, something denied the explorer after his untimely demise.

"We aren't looking for one outcome or another," says Bowen, who serves as vice president of the Locust Hill Graveyard Foundation, named for Lewis' childhood home which is located on what is now Owensville Road in Ivy. "We are neutral."

For Thomas McSwain Jr., Lewis' great-great-great-great nephew and president of the Locust Hill Graveyard Foundation, the gap in the historical record bothers him most.

"It should matter to everybody, the veracity of our historical record," says McSwain. "If he was murdered or assassinated, what else about our history do we not know?"

Bureaucratic battle

The combined struggle of family members and researchers to obtain a permit to exhume Lewis' body has lasted a decade, starting with a two-day coroner's inquest in 1996. The inquest, a government-assisted fact-finding mission with witnesses and jurors, recommended exhumation to obtain more evidence.

Starrs, the family's chief investigator, helped set the inquest in motion. The George Washington University professor is an established name in the world of forensics, and his previous exhumations include Wild West outlaw Jesse James as well as Albert DeSalvo, the alleged Boston Strangler. For Starrs, an exhumation of Lewis is a refreshing change of pace.

"It's awfully nice to deal with somebody who is a hero of his own making," says Starrs.

With worries of their application being denied, the family has gone on the offensive, finding a public relations firm and launching a website, solvethemystery.org, to promote their mission. Taking advantage of their new outreach capabilities, their story has been published nationwide.

Since that initial hearing in 1996, the family has seen itself close to landing the permit only to be denied. Part of that is due to the rules for National Park land.

Since Lewis' body rests in the Meriwether Lewis Park, administered by the National Park Service, the case for exhumation hinges on two environmental laws: the Archeological Resources Protection Act, better known as ARPA, and the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA.

While ARPA requires that approval be given prior to digging up any historical artifacts on national park land, NEPA requires an environmental assessment before an archeological dig, with time for public comment.

However, new opinions on the case, including one from Lyle Laverty, assistant Secretary of the Interior for fish and wildlife and parks, have given some hope to exhumation-minded family members. In a January 2008 letter, Laverty calls the proposed exhumation "appropriate and in the public interest." A follow-up by the acting director for the National Park Service confirmed Laverty's view.

This means the last major hurdle for the family and investigators is the environmental assessment, which will be completed by an Arizona-based firm called SWCA Environmental Consultants. Calls left with SWCA were not returned.

"Once it's completed, the results of the environmental assessment will determine the parameters for which the exhumation can take place," says Bill Reynolds, spokesman for the National Park Service's Southeast region.

David Vela, southeast regional director for the National Park Service, would then be responsible for making a final determination. Vela declined an interview request from the Hook.

The family, represented through the Locust Hill Graveyard Foundation, will be the ones paying for the assessment and any resulting exhumation. McSwain says the family looked primarily for pro-bono help to keep prices down. However, McSwain added that the family had spent $5,000 in the past six months, but should an exhumation be approved, the family could spend as much as $300,000 and seeks ways to raise funds to cover the costs.

Starrs is confident that the new support will bring positive results.

"The National Park Service will have a tough time rejecting us," says Starrs. "We have a clean slate to work with this time."

Answers buried below

Should the family receive final permission to exhume the body, it would set in motion a documentation process including taking down the stone monument over Lewis' grave. After working with construction crews to move the statue, researchers would methodically work their way down, taking notes and pictures from each step of the dig. Upon reaching the grave, the team would sift through the dirt looking for cultural artifacts such as coffin nails.

Following this rigorous digging process, it will be Hugh Berryman who will then analyze Lewis' body. The director of the Regional Forensic Center in Memphis and a professor at Middle Tennessee State University, Berryman was a part of a Smithsonian team that examined Kennewick Man, a 9,300-year-old specimen found in Washington state in 1996.

According to Berryman, a subject's bones can reveal height, age, sex, ancestry, and even medical background. "Bone is tremendous in recording its own history," says Berryman.

According to Starrs, any hairs found with the body might indicate potential drug use or illnesses as well. "Hair can tell us a lot about a person," Starrs says.

Besides the alleged head and torso injuries, other wounds on Lewis might be found, including a bullet Lewis took in the buttocks in a hunting accident returning from the expedition. Speculation has it that fellow party member, Private Cruzatte, blind in one eye and near-sighted in the other, mistook Lewis for an elk.

"He [Lewis] described it as the upper thigh in his journals," Thorp says. While the wound was not life threatening, Lewis had to spend several days on his stomach as his party canoed.

However, the most important physical evidence researchers hope to find are bullet wounds to the head and torso, as described in accounts of his death.

"I'd like to see those shots," says Berryman, whose research focuses on bone fractures including blunt, sharp, and most important for this case– gun– trauma. The distance that the gun was held from Lewis' body and the angle of bullet entry could quickly resolve the debate.

"If they're [entering] back to front, then that is not a suicide," Berryman stressed.

The exhumation itself would take about a day, with the full autopsy taking about a week.

"We have to consider the park as well," says Berryman. "We want to put it back as quickly as possible."

There are some concerns that Lewis's remains may not be preserved after 200 years.

"If ever we need to do this, we need to do this now, while there's a reasonable chance of this happening," says Lewis descendant McSwain. However, some factors give researchers reason for hope.

One factor is his resting spot. The grave's location on top of a hill in Meriwether Lewis Park has been helpful in keeping water away from the remains, along with the placement of a monument atop it.

"It's like putting a roof on this thing," says Berryman. Tests of the soil acidity have shown positive signs as well.

"The soil is very alkaline, so it will not do serious damage to the bones," says Starrs. The fact that Lewis' remains have been unearthed only once since his death also gives hope to Starrs about the quality of the evidence.

"There's no contamination," says Starrs. "The bones should be how they were."

What next?

For now, the family must wait for the results of the environmental assessment. A compounding issue is that since the family works primarily with college professors, the best time to work is during breaks, occurring most often in the summer.

"If you miss an opportunity to do it in the summer, you miss out on a whole year," says McSwain, adding that, at best, the earliest the exhumation would happen is summer 2010.

For the time being, the family will do its part to commemorate the bicentennial of Lewis' death, which falls on October 11. The family is preparing for ceremonies to dedicate new plaques for Lewis both at his Tennessee grave on October 7 and at the Albemarle courthouse September 19.

Despite his family's difficulties finding answers, McSwain remains optimistic about solving the mystery.

"We're trying to find the truth," says McSwain. "The only way for us to do that is to exhume his remains."

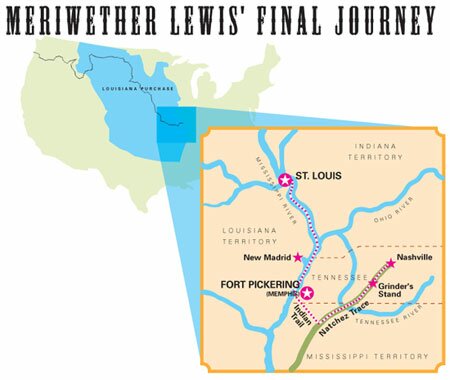

Fateful path: the final journey of Meriwether Lewis

Lewis left St. Louis on September 4, 1809, with plans to return that December. He stopped at Grinder's Stand on October 10 and was found dead the following morning.

map by Allison Sommers

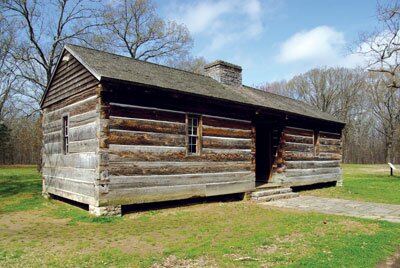

Lewis died at Grinders Stand, an inn along the Natchez Trace, and was buried without ceremony near the inn's stable. (This is a not-quite-faithful replica built by the Civilian Conservation Corps.)

photo by Sharon Murray

Experts says this stone memorial, erected by the state of Tennessee in 1848, has protected Lewis' remains from excessive deterioration.

National Park Service

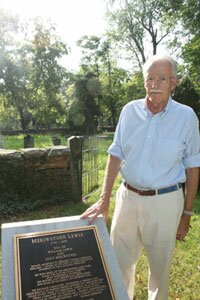

Relatives such as Howell Bowen, who lives in Albemarle near his ancestor's home, want to exhume the famed explorer.

Photo by Gordon Block

Lewis was born in Ivy, one of six siblings on the family's 2,000-acre plantation, Locust Hill. (The place is currently 2.34 acres fronting Owensville Road and offered for sale at $2 million.) [Correction: Even before this article appeared, the price was lowered to $1.495 million.]

Photo by Gordon Block

Forensic authors James E. Starrs and Kira Gale gave a talk about their research in late May at Charlottesville's New Dominion Bookstore.

Photo by Gordon Block

"I fear this report has too much truth," wrote co-explorer William Clark after reading a Tennessee newspaper report of his friend's death, "tho' hope it may have no foundation. I fear the waight of his mind has over come him."

Independence National Historical Park

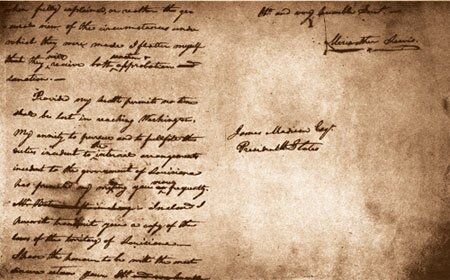

Lewis penned his letter just after arriving at Fort Pickering. While the dozen-plus additions or strike-throughs lend credence to the suggestion that his mind was troubled, the cross-country effort to get paid suggests a man very interested in living.

Missouri Historical Society

#