COVER- Still filthy, still fun: The respectable John Waters

PUBLICITY PHOTOS

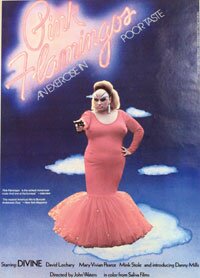

In the 1970s, John Waters was the bad boy of fringe filmmaking with his cult-classic, X-rated Pink Flamingos. Flash forward more than 30 years, and he's the guest of honor at Mr. Jefferson's U, and the Virginia Film Festival is showing the now NC-17-rated picture that still you don't recommend for your mama– unless she's one of those who fell under the sway of Waters' magical filth so many decades ago.

Waters moved from extreme film to mainstream in 1988 with Hairspray, which is also being screened at this year's film fest. He's made 16 movies, including Serial Mom and Cry-Baby, written five books, published collections of his photographs, released music compilations such as A John Waters Christmas, and staged art exhibits.

And over the years, he's crossed paths with some of the most memorable characters of the late 20th century: Divine, Manson follower Leslie Van Houten, kidnaped heiress Patty Hearst, and Johnny Depp.

Baltimore, his hometown, has been the setting for most of his movies. Some people see Baltimore through the lens of The Wire; our Charm City has always been Waters tinged. But we catch up with him recently by phone in New York.

Hook: What did you do today in New York?

John Waters: This morning, I wrote my 10 best films list for Artforum. Yesterday, I had to write a speech that I gave for the design awards last night that I gave to a company called Boym, which builds these little things called Buildings of Disaster, which are four-inch, nickel-plated replicas of everything from the Oklahoma federal building to Waco to the Unabomber's cabin, and I presented them with the award. And today– every morning I have to think up something and sell it in the afternoon– and this morning, I just turned in the copy-edited version of my book, which I've been working on for two-and-a-half years. It's called Role Models, and it comes out next May from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It's my memoirs told through people that have excited me and impressed me, everybody from Dora the lesbian stripper in Baltimore to Tennessee Williams to Madalyn Murray O'Hare to St. Catherine of Sienna. Quite a pack.

Hook: We read an excerpt of that.

John Waters: It was Leslie Van Houten...

Hook: It was quite revealing.

John Waters: Well, that's probably the only serious chapter in the book. The only thing that's happened new from that chapter is one of the three [Manson] women has died recently. Susan Atkins would have been the last of the three to get out, but she's the first to get out. In a box.

Hook: What should have been obvious to us was that Multiple Maniacs and Pink Flamingos were inspired by the Manson–

John Waters: Were influenced, not inspired, influenced by. Multiple Maniacs– we took credit for the crime before they caught them. That's really horrible. And come to think of it, Multiple Maniacs was a dress rehearsal for Pink Flamingos, I mean, Divine ate a cow heart in that; that was training wheels. It glorified violence in a comic way which people had not really done then, for a hippie audience. So what it was was punk, but we were just five years too early.

Now you can go to the drugstore in middle America and buy the exact same hair color that Mink Stole had and David Lochary wore in Pink Flamingos. At the time, they had to strip their hair of all color and dye it with magic marker and peacock blue fountain pen ink to get that color.

What's interesting to me about that movie– it's not my best movie, but certainly it will be right in the first paragraph of my obituary, no matter what I do the rest of my life– it didn't get nicer. Nineteen-year-olds today have the same reaction to that movie as 19-year-olds did in 1972. So I'm proud of that. That's hard to pull off.

Hook: So how do college students react today?

John Waters: When I go to colleges– and I go a lot– the average age, even in New York, if I have a new DVD come out and I do a signing, the average age is 23, and I'm 63. So that has always been the only crossover that counts to me. When they use the word crossover in the movie business, they mean money, they mean going over to middle America. I've only had one movie that did that. It was Hairspray. But oddly enough, they all play on television now. Who would have ever imagined that?

And you look at that movie, and what has changed. It was supposedly shocking they sold babies to lesbian couples. Now lesbian couples have more kids than Catholics. That's really the only thing that's different. Of course when they kidnaped the girls and impregnated them, that's still not politically correct.

Eating dog sh*t was not technically illegal then, and that's why we did it, because that's the year Deep Throat became legal, but as a joke– what can you do that is worse than pornography but isn't illegal yet. And it is illegal now.

Hook: Really?

John Waters: Yeah. In porno, there's only three things [you can't do]– two things, now. They can show urine, and it didn't used to be. They can't show sh*t or pedophilia. But the difference is, we certainly were not doing it for sexual reasons. There's nothing sexual about that scene. It's about anarchy. The same way I've always said Johnny Knoxville [of Jackass] would have done that if I hadn't. But he didn't have to. And I've told him that.

Hook: At the film festival here in Charlottesville, Pink Flamingos is going to follow Hairspray.

John Waters: [Laughs.] That's kind of an interesting double feature. I totally understand that they're opposite ends of the spectrum of John Waters movies. But I think they're the same. They talk about an outsider winning, an outsider being confident, about minding your own business, what's right should be right, and don't judge other people. Pink Flamingos says it in a much more aggressive way, and Hairspray says it in a much more socially redeeming way. But I didn't plot that.

When I wrote Hairspray, Divine was supposed to be both the mother and the daughter, kind of like the Parent Trap. But Divine was 40 or so when we made that movie. So he was the mother.

But in Female Trouble, which we made in 1974, he was 28 or 30, but he then played a teenage high school girl and it was quite funny. That movie is probably the most popular and the most long lasting of my Divine movies. I think it's a better movie than Pink Flamingos.

Hook: When was the last time you were in Charlottesville?

John Waters: When I came to visit Sissy Spacek to see if she'd be in my movie, and she didn't.

Hook: Which one?

John Waters: Let me think. It was probably Pecker. I didn't take it personally.

My two sisters live in Virginia. One lives in Alexandria, and the other one lives very deep in Virginia. I'll tell you where. I'm looking it up. I go there all the time. I'm going there for Thanksgiving. I just can't remember the name of that town...

And both my sisters went to Sweet Briar, and my mother went to Sweet Briar. And it's certainly an irony that I get invited there to speak.

She lives in Bridgewater, Virginia. It's in the middle of the Bible Belt. My sister loves it. I go there every Thanksgiving. It's very near a turkey Auschwitz. There's the most shocking turkey, poultry [facility]. Really, it is Auschwitz, and it's really booming right before Thanksgiving. It's not especially empty. But we always go by it, and it's always so alarming for me to see it, and it really is huge.

Hook: At least your turkey will be fresh.

John Waters: I guess she got it there.

Hook: Back to your memoir. There's this one line. You say you're "guilty of using the Manson murders in a jokey, smart-ass way in my earlier films without the slightest feeling for the victims' families or the lives of the brainwashed Manson killer kids who were also victims in this sad and terrible case." What caused that realization, or have you had a change of perspective?

John Waters: I went to that trial, and to me, it was the first real media sensation, way before OJ. It was greatly theatrical, and at the same time, the Manson family was everything every parent was worried their kids would turn out to be. And then I taught in prison, and I took it seriously. I read books about victims. And so it wasn't anything that happened over night. Doesn't everybody do things when they're young that they regret? I don't regret any of that, but I look back on it and realize it was kind of wrong-headed.

But what has happened since then is that no one knew that Manson was going to turn into a Halloween costume, that it would never end. Even Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor, he said in the original Helter Skelter that the girls would do 20 years.

It gets more and more notorious each day. Susan Atkins dies, and then Polanski gets arrested. The story never ends. And one hopes, if Manson dies, will that help Leslie? But I say he'll outlive Keith Richards. It is a story whose endless running time is way beyond the expiration time everybody thought it would have.

Getting to know Leslie, to look back on that and imagine, because she really believed, it's almost impossible to understand that they thought they were doing the right thing. And now, what can she say? It's the most horrible, horrible kind of realization ever to come to terms with. And yet, she can never ever change that, and she's changed everything else she possibly can. She has become now the woman she would have been if she hadn't met him.

I have always been drawn to extreme lives, and to questions with no fair answer. If there's a fair answer or easy answer, I'm not that interested.

Hook: What was the last thing that shocked you?

John Waters: I like to be shocked at contemporary art. The kind I like makes me mad, and then I end up buying it. I saw [Lars von Trier's] Antichrist and I loved the movie. It's like an old-fashioned shocker. I don't like reality TV. Most of it is offensive to me because it's classist, and it's asking you to feel superior to the people you're laughing at, and I really don't think I did that in my movies. And reality shows almost always do. And people's endless capacity for humiliation to be famous was new at the beginning but it's getting really tired as a subject matter.

Hook: Yeah, you covered that so long ago.

John Waters: Yeah. I don't really feel bad for them any more. I just click. I don't want to watch it.

Hook: So can we expect another movie from you?

John Waters: I hope. But I don't know any director in my world that is getting a $5- to 7-million independent film made today. There aren't any. If you look at Sundance this year, only one or two movies sold for over a million dollars. Toronto this year– nobody bought anything. New Line, all the companies I dealt with are gone.

But I'm in the middle of it. I'm thinking up a whole new one. I've got two, really, and I just had a meeting about them yesterday. I don't give up. I've been doing this for 40-something years. Fruitcake, my children's Christmas movie has almost gone twice and fallen through at the last minute. I think it will [get made] eventually, but the economy has played havoc on independent film.

Hook: That's too bad because we heard you speak years ago and you mentioned the trouble getting funding.

John Waters: It's never been easy to get a movie made in my whole life. Once it was. Cry-Baby, because Hairspray had just come out, and it was a hit. That was the only time. And the only time I really had enough money was Serial Mom. But I'm not whining. Because if it was easy, wouldn't everybody make movies? They think they can get laid, they'd go to good parties, they'd get to travel first class– wouldn't every person in the world? There'd be no other careers. Everybody would like to be a film director. You get to boss people around, and you get to travel. But the reality of it, even James Cameron, when he was making Titanic, he had to put his own money in at the end.

Hook: You mentioned Cry-Baby, and we have to ask the obvious. What was it like to work with Johnny Depp?

John Waters: Johnny didn't want to be a teen idol, and he was at the time. I said, come with us, and we'll make fun of it. The same way I did in that movie for Traci Lords. She was escaping porn; and I said, let's make fun of it. Patty Hearst– who wants to be a famous victim? She said she'd never signed an autograph until she made a movie with me. Who wants to sign an autograph because you were kidnapped? I had a critic once at the beginning of my career who said it wasn't fair that I beat the critics to the typewriter by calling it a trash epic. It's the same principle. You embrace the negative things and exaggerate them and make them your style. And then they can't use it against you. Well, they can, but...

Hook: So, do you ever think about shaving off your mustache?

John Waters: You know, one time I thought about it for an art project, what would it be if I just filmed it, like a loop that would play over and over again, and that's the only time I thought about it. Well, even if I had to go underground, like if I committed a crime and I wanted to go in disguise, I guess if I shaved it, and wore a wig, and let a beard grow that was gray and wear a baseball cap, that I could really get away with it. But no. Every day, I don't debate that. Should I? No. I don't even know I have it. I've had it since I was 19 and I'm 63. If I did shave it off, I think it might be like, it is where the sun don't shine.

~

John Waters' talk, "This Filthy World," at 4:30pm Friday, November 6, at Culbreth Theatre, will have a limited number of tickets released at the door that day. Hairspray screens at 7pm, Friday, November 6, at Newcomb Hall. Waters introduces Pink Flamingos at 10pm that evening, also at Newcomb Hall.

And he drops by the "Dirty Pink Polyester" Dance Party at the Southern from 10pm Friday to 2am. Drink o' the night is the Pink Fetish, and the ladies of CLAW and the C-ville Derby Dames make a special appearance. Tickets are $10– $5 for 21-year-old UVA students.

#