COVER- Pod in the quad: How Albemarle students became palm readers

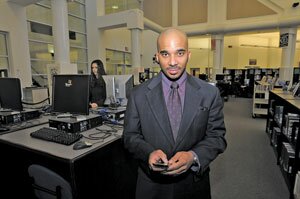

Luvelle Brown

PHOTO BY SCOTT ELMQUIST

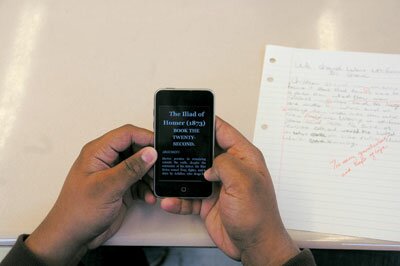

To Albemarle Public Schools technology chief Luvelle Brown, the iPod Touchs he introduced in classrooms two years ago aren't just music players. They're textbooks, notebooks, tape recorders, video screens, and neatly self-contained digital classrooms– all in the palms of student hands.The "aha" moment literally snuck up on IdaMae Craddock. It crept quietly as she allowed a seemingly harmless Trojan horse through the gates of her advanced English class at Monticello High School. It arrived in the form of a few dozen 4-inch-by-2-inch, black-and-silver electronic boxes: iPods.

"I was blown away," Craddock says, recalling the lesson a few months ago when Homer's famous story the world's most famous sneak attack came to life on tiny screens of her students' school-issued iPod Touchs.

Craddock's pupils allowed themselves to be overrun, first by multiple e-book translations of the 4,000-year-old classic, and later by a National Geographic video about the Trojan War and its weapons, watched on YouTube. Then, via satellite maps on Google Earth, the students swooped in on modern-day Turkey's west coast to where the remains of the ancient Troy were excavated two centuries ago.

Fingers typing instructions on the touch-screen keyboards of their devices, the kids overlaid the digital maps with a computer simulation, watching the simulated shift of the ancient battle lines as Greek warriors moved into the ancient city and overwhelmed it.The ensuing discussion among high schoolers– whether the statue-borne ending was historic reality or simply one of the world's greatest examples of literary fiction– was among Craddock's most vivid classroom experiences.

"This was the moment where I realized I'd become totally dependent on these iPods," says Craddock, 33, who admits to being one of the County's biggest skeptics before she plunged headfirst into the Albemarle iPod program two years ago.

Now she's a believer.

"It's just a better pencil," says Craddock. "I could have done the whole lesson on my overhead projector, but it wouldn't have been the same."

Though most adults still struggle to comprehend the computing power packed in these relatively cheap and commonly available hand-helds, many children and teenagers are well aware. iPods and their cousins, smart cell phones, boast a dizzying array of functions– including cameras, video and audio recorders, powerful word-processors, fast Internet access, and book readers. They also enjoy the ubiquity that comes with vital communication devices.

Whether branded by Apple or Motorola or disguised as a cell phone, music player, or pocket video game, the handheld computer is increasing becoming both the Trojan horse and the beautiful Helen of Troy— a digital face that may well launch a thousand educations.

Immigrants and natives

Despite their utility and widespread consumer acceptance— and despite the interest of many tech-friendly educators— the cell phone officially remains an enemy at the gates to nearly every school district in America. But Albemarle is a smart-phone island, awash in a sea of laptop initiatives.

Closer to the capital, Richmond Public Schools and the surrounding suburban school districts, like most school systems, prohibit cell phones and other handhelds. And that needs to change, says Gary Sarkozi, director of technology at Virginia Commonwealth University's School of Education.

"The biggest thing we have is realizing the difference between digital natives and digital immigrants," Sarkozi says, suggesting (as Craddock does) that today's student brains are wired differently from those of kids just five years ago, before wireless Internet and text-messaging connectivity became so widespread.

Four of five teens carry cell phones, says Sarkozi, citing a 2008 wireless industry study. But while 57 percent say having a cell phone improved the quality of their lives, only eighteen percent of kids responded that cell phones had positively affected their education, perhaps because nervous educators have kept them out.

"The uneducated [educators] just say, ‘No, no, no, I'm not going to have it in my school— somebody might sue me,'" says Sarkozi. "But today's students are mobile. The policy must become less stringent."

It's easy to understand why some educators are reluctant. They worry not just about lawsuits, but also about inappropiate pictures, digitally-assisted cheating, and loss of classroom peace to the din of computer games.

"Cell phone policies in schools have been a roller coaster," says Kirk Schroder, former president of Virginia's State Board of Education, recalling the mid-1990s when cell phones first began showing up in backpacks. "They were seen as devices that were distractions to the learning environment."

Then came Columbine.

On April 20, 1999, a dozen Colorado school children, a teacher, and two troubled teenaged shooters died in the worst mass shooting at an American high school. Dramatic reports of the attack came from pupils' frantic cellphone 911 calls.

"They became critical devices," says Schroder, citing the fleeting time between Columbine and the invention of the camera phone, its abuse by pupils "sexting" each other by sending nude photos– and the resulting renewed classroom pariah status that phones earned.

Through it all, Schroder says, the mobile phone has slowly amassed greater applicability to learning, and kids have been at the forefront of helping them morph from mere phones to pocket computers. So it's time for educators to once again re-evaluate their policies on cell phones, VCU's Sarkozi says.

"There needs to be an upfront policy: You abuse the privilege, you don't have the privilege," says Sarkozi, who contends that students so appreciate the mobility that they're unlikely to abuse it.

However, Luvelle Brown, Albemarle's chief information officer, believes rule-breaking is inevitable. But that didn't stop him from doing something big.

Free iPods in Albemarle

While local districts including Fluvanna and Charlottesville now allow students to bring their own phones and iPods into school for breaks or with teacher permission, Brown took Albemarle much further, actually giving iPods to county students– including Craddock's class.

Perhaps the best part: the iPods were free. During a promotional period, each of 1,100 Mac laptops the division leased came with an iPod.

Replacements have thus far not been an issue, says Craddock, who notes that each of the Albemarle iPods is etched with the school district's information– something that allowed one to be returned after a boy left it in the American Eagle store at Fashion Square mall. The school's iPods are also locked to prevent adding or deleting programs– and to make them less alluring to would-be thieves.

"If you did steal them, yay," laughs Craddock. "You get six copies of Gilgamesh!"

Brown–- earning praise for his leadership from superintendent Pam Moran– says the key to preventing problems is to develop policies and punishments before leaping in, and to ensure that educating pupils on digital ethics part of the curriculum.

"We couldn't allow 1,100 iPod Touchs to go home without having kids understand what they could and couldn't do," says Brown.

That education works both ways. The iPod Touchs— basically iPhones without the telephone— are allowed out of the building. Personal cell phones and personal iPods are, likewise, allowed in.

"If we, as educators, continue to power down students when they come in the door," Brown says, "we're not going to close that global achievement gap."

Brown has plenty of firsthand knowledge of the risks that come with unlimited access. He was a Henrico technology specialist seven years ago when that county's superintendent ordered 24,000 Apple laptops and sent them home with every middle- and high-school pupil. The initial result of the experiment— today considered a success— was disaster compounding disaster.

Henrico failed to plan beyond the day that Pandora's box was opened. The network crashed, kids downloaded porn, the county lacked digital classroom material, and server space filled up with downloaded music files. Superintendent Mark Edwards took a lot of heat.

"Mark and I talked a lot about that venture," says Bill Bosher. The former Virginia superintendent of schools was superintendent of neighboring Chesterfield at the time, and Bosher audibly winces at the memory.

"To give every child that kind of access," says Bosher, "I thought it was a very courageous initiative."

Courageous and perhaps inevitable, according to Elliot Soloway, a professor of computer science and engineering at University of Michigan.

"I'll make a prediction," says Soloway. "In five years, every child in every grade in every school will be using a mobile computer for learning."

Alemarle's Brown acknowledges that he's done a bold thing by giving out technology and permitting even more of it to enter the building unchecked. Clearly, he's thinking ahead to a time when one school district's Achilles heel becomes a moot issue. As Superintendant Moran says, relevant technology is "no longer a luxury."

And what makes the smart phone different from the laptop— or even from much-ballyhooed tablet computers that Apple just announced— is that smart phones aren't destination devices. They are, Soloway says, an extension of a student's arm.

"In the past," he says, "adults brought laptops into classrooms, and those were parents' computers. Mobile computers are kids' technology."

Soloway predicts that tablets, like laptops, will remain a supplemental class tool like laptop or desktop computers, because it's unlikely that they'll become as widely available, or as widely adopted into daily life as the pocket-sized cell phone.

"This mobile stuff is the only way we're going to eliminate the digital divide," Soloway says. "It's at a price point where everyone can afford it."

Every student touches a Touch

A recent Pew survey on American internet use gave a glimpse into just how affordable. African-Americans, a demographic traditionally underserved by new technology, are 70 percent more likely than whites to access the Internet using handheld devices.

For Albemarle's Brown, price was critical. A laptop might cost $1,000 or more, but an iPod– when not arriving as a freebie– is less than $200. And so far they've ridden on Monticello High's existing wi-fi network.

Ironically, even as they enjoy an expanding market for their products, manufacturers of handheld devices don't seem to holding up Albemarle as an example.

"The jury is still out on the efficacy of mobile learning," says Michael Quesnell of phone-maker Nokia Corp., and Quesnell hesitates to call smart phones a silver bullet for technology in education, despite his company's participation in ongoing studies.

Even at Verizon Wireless, which markets a variety of smart phones for the national cellular provider (including the powerful Motorola Droid), the manager of government and education sales doesn't envision a time when pupils bring their own handhelds to class. He believes the future is in contracts between cellular providers and school districts, which, he predicts, will continue to buy the computers and supply them to children.

"You give up control when you allow students to utilize their own technology," cautions Horton.

Brown enthuses that Albemarle has thrown such caution to the wind. Ironically, he says, when he first approached Apple two years ago about getting iPods for his classrooms, even executives with the pathfinding company seemed somewhat surprised.

"No one was using iPod Touchs in education," explains Brown. "Now, I would say every child in our division has touched one."

One of Craddock's students, Audra Brown, likes the idea of lugging fewer textbooks. And even though she reports occasional trouble getting online (something that can makes homework a challenge), she's glad her school's making the leap to high tech.

"I like it a lot better than textbooks," says another of Craddock's students, Mason Shiflett. "You can get info a lot quicker."

Because iPods are still in short supply in 12,000-student Albemarle, laptops and tablet computers remain vital; but the County's spending on textbooks has been dramatically altered. The textbook replacement fund, now dubbed the "learning resource fund," dropped from over a million dollars a year to a just a couple hundred thousand dollars, Brown says, because many books and source materials are free content online.

"Our teachers aren't asking for new textbooks," he says. "They're asking for electronic devices."

~

Chris Dovi wrote a version of this story as a reporter for Richmond's Style Weekly, where the story first appeared. Dovi left that paper in mid-February amid great controversy. More on that in this week's back page essay.

#

Even the future of testing gets a second look when pupils' classroom activities happen in a digital environment, where progress is monitored by a teacher on a question-by-question basis, says Gary Sarkozi, director of technology in Virginia Commonwealth University's School of Education.

"The iPods have put the control in their hand," says Monticello teacher, IdaMae Craddock, left. Monticello High student Jacob Paulansky navigates an iPod Touch as classmate Joel Selig looks on.

Kids today expect to learn in a digital environment where they control and manipulate information in ways impossible using paper textbooks and overhead projectors.

Smart phones and handheld computers– already by many kids an extension of their own hands– are cheap, common, and leading some education experts to question schoolhouse bans on such gadgets.

#

5 comments

One has to wonder what Luvelle Brown means when he says that the use of iPods (cell phones, etc.) will help educators close "that global achievement gap." Most likely he is referring to the scores of American students on PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment). But nobody really knows exactly what PISA scores measure about learning, since most of the questions and their underlying metrics remain under wraps. A significant number of researchers say that PISA IS sensitive to and DOES represent a measure of a nation's socioeconomics. And of PISA nations, only Mexico has a higher incidence of poverty.

If Brown really believes the use of iPods will affect PISA scores.....well, there's some nice oceanfront property in Kansas he may be interested in.

As to the Henrico "experiment" with laptops, the so-called study done on that is a correlational one that has little rigor. The study coincides with the No Child Left Behind legislation, and all the emphases states and school districts have placed on testing and test scores. in Virginia there's been real classroom focus on teaching to teh SOL tests....it'd require a very strong experimental design to show laptops boost achievement....Henrico cannot show that. Moreover, at a cost of $8 million a year, there are surely a host of other measures to boost achievement. The Henrico survey, in fact, finds that the laptop program had little impact on student motivation to learn.

Technology is a tool, and as surely as it's a part of everyday lives it too has use in the classroom. But it is no panacea....and in some cases it can impair focus and deep learning (as when people or students continually multi-task, shifting their attention from one thing to another repeatedly).

The use of iPods may be fun....but that doesn't mean they help students learn well. Nowhere in the article, for example, was there any mention of what students learned form their iPod lesson (the teacher said it could've been done on the overhead projector...).

D-mocracy - I'm not sure anyone said it was a panacea?

I always find it interesting to read sofa-based critic responses to articles. I always wonder, as well, what backgrounds these critics bring to their posts. I suppose there must always be the naysayer, and the one who feels compelled to immediately turn something exciting into something negative. Sad.

"I always find it interesting to read sofa-based critic responses to articles."

I always find it entertaining to read the reply post verbiage from someone who disagrees with a post. You softly put down the poster and try to elevate your own post to a higher standard. LOL

Reality didn't like the critique, but didn't address any element of the commentary. Instead, Reality just swept aside the relevant points as "negative" and called the commentary "sad." In other words, when you don't like the message, try to discredit the messenger.

One doesn't need, for example, to have personal experience with cocaine or heroin addiction to opine that the use of them might not be worthwhile, even if it could be termed "exciting."

The gist of the article is that technology IS, in fact, an educuational panacea even if that particular word isn't used. The article begins with this: iPod Touchs are "textbooks, notebooks, tape recorders, video screens, and neatly self-contained digital classrooms." It later quotes Luvelle Brown as saying that ""If we, as educators, continue to power down students when they come in the door "we're not going to close that global achievement gap."

Now, what does Reality take from this?

In an analysis of the Third International Math and Sciences Study (TIMSS) researchers found that in high-scoring Japan "teachers believe in maintaining a complete record of the entire lesson (on the blackboard) which offers both slow and fast students opportunities to revisit ideas as needed and thus deepen their understanding," one reason

why Japanese students outscore American students in math and science.

Not "exciting," but effective.

Geez, I remember the ballyhoo that accompanied the introduction of chalk. And here we go again! Does Brown believe his own hype?