COVER- Fishing pols: Shad Planking draws big names, bony food

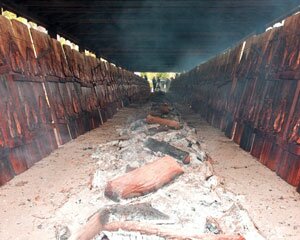

A smoky, oak-stoked fire gives the shad at distinctive mahogany color.

The 62nd annual Shad Planking was celebrated April 21 near Wakefield in southeastern Virginia. George Allen was there. So was I.

This annual paean to politics, shad, and some favorite beverages is held on the third Wednesday of every April. Twenty dollars gets anyone in.

The Shad Planking started as a yearly party of friends in the 1930s at Wrenn's Mill in Isle Of Wight County, celebrating the spring shad run up the James River by cooking the fish on oak planks. It slowly became an important Democratic political event back when the Democratic machine would choose gubernatorial candidates, who would routinely win elections.

The Wakefield Ruritan Club took over in 1949 and has hosted the event as a local fundraiser ever since on the wooded property of the Wakefield Sportsmen's club. It was exclusively white and male for years, but in 1991 Doug Wilder was the keynote speaker.

The Shad Planking now serves as a bipartisan, and largely symbolic, launch to Virginia's election season. But is it coincidence that gubernatorial candidate Creigh Deeds skipped the 2009 event while his eventually victorious opponent Robert F. McDonnell attended?

***

The featured star of the event is Alosa sapidissima, the American Shad. According to my 1927 copyright Junior Classic Latin Dictionary, Sapidissima means most savory; but perhaps it should also also be called osseissima, or most bony. An Indian shad creation legend has it that "there was a porcupine that was unhappy with its place in the world, so he asked the Great Spirit to give him a better situation in life. The Great Spirit turned him inside out and threw him into the river."

A lighthearted recipe for planked shad goes like this:

1: Clean and scale the shad and split it open from head to tail.

2: Preheat an oak plank in front of hickory coals and grease with butter.

3: Place the shad on the hot board with the skin side down and fasten it securely with thumb tacks.

4: Stand the plank on end at a 60-degree angle in front of the coals.

5: Baste frequently with melted butter and shake salt and pepper over it.

6: When done, remove the tacks, throw the shad away, and eat the plank

The Virginia Department of Game and Fisheries website teaches us that American shad are anadromous, i.e. living primarily in the ocean but breeding in fresh water. As adults, they travel in large schools along ocean coastal areas for four or five years, until sexually mature, and then run up large rivers from saltwater to freshwater to spawn.

After spawning, the surviving adults return to the ocean, while newly hatched young remain in freshwater until fall, when they move downstream to brackish estuaries where they may remain for a year or more before moving out to the ocean.

The shad was a popular and important food for early America, so important that Pulitzer Prize-winner John McPhee named his 2003 book on shad The Founding Fish.

Thomas Jefferson knew shad. He was born at a farm on the Rivanna River called Shadwell. He ate his fresh shad "laid open, broiled, and addressed with salt, and butter."

The huge spring runs upriver to spawn in March and April coincide with the blooming of the shadbush, or serviceberry. Coming at the end of winter, such runs were welcome, and sometimes lifesaving, to hungry Colonists. Historian Robert Beverley wrote in 1705: "In the spring of the year, herrings come up in such abundance... to spawn, that it is almost impossible to ride through, without treading on them."

However, overfishing, pollution– and especially dam building– decimated their populations. In 1980, Maryland banned commercial shad fishing. Virginia followed suit in 1994, and commercial and recreational fishing for American shad continues to be banned Chesapeake Bay-wide. The only people in Virginia allowed to harvest shad are Native Americans. Hatcheries on the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Indian reservations have returned millions of young shad to the tribes' and Commonwealth's rivers.

My Shad Planking ticket says that the event starts at 2pm, ends at 6:30pm, rain or shine, and sternly warns, "Food Served When Ready."

The menu begs a question. If it's illegal to catch shad in the Chesapeake Bay, where are all these fish coming from? Reportedly, they are imported from commercial fisheries still operating in North Carolina and Delaware.

Back in Charlottesville, at the base of the Rivanna Reservoir, the gizzard shad run is underway. Hundreds of gizzard shad are trying to muscle their way up the dam spillway. They can inhabit fresh and brackish waters, reservoirs, lakes, estuaries, and occasionally marine waters. As filter feeders, they consume plankton, microcrustaceans, and protozoans. Due to the likelihood of ingested PCBs, the Virginia Department of Health recommends no more than two meals a month of gizzard shad from the Rivanna, but most anglers consider them inedible anyway, inaffectionately calling them Mud Shad. This unpopularity is bolstered by the fact that gizzard shad, due to their vegetarian habits, won't take a baited hook.

The past few springs, as this one, I unsuccessfully dangled a popular shad lure, called a shad dart, in the water in front of the Rivanna Dam. American shad, while carnivorous otherwise, also don't take bait after they start their spawning run. Then why am I hoping they will bite the shad dart? The predominant theory is that they find the dart irritating, and snap at it to get it out of their face. (Perhaps they are peevish after several weeks of no breakfast.) And what makes me think I have any chance of catching American shad after over 100 years of absence from Albemarle waters?

All but one of the barricading dams has been removed from the James River watershed, including most recently in 2007, the Woolen Mills Dam in Charlottesville. The remaining dam, Bosher's Dam on the west side of Richmond, has a fish ladder.

In addition, millions of shad have been stocked in the upper Rivanna over the years. Michael Odom, Manager for Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery in Charles City tells me that his facility released 1,002,000 American shad fry into the Rivanna in Fluvanna in 1999. In 1993, 10,000 fish were released at the edge of Charlottesville. In 2005, 500,000 were released. In 2006, 400,000, and in 2008, 468,470 fry were released. Where are all these fish?

***

We approach the Shad Planking on U.S. 460. Chalk-line straight and Tidewater flat, the four-lane road is a popular beach route, running from Petersburg to Suffolk and passing through farm land and small towns including Disputanta, Waverly, Wakefield, Ivor, Windsor, and Zuni. That last town (established in 1736 and pronounced "zoo-nye") conjures pueblo fantasies of wayward Spanish explorers. Town historians, however, admit they have no idea how it got the name.

In Waverly, one can stop at the First Peanut Museum. In addition to showcasing myriad goober memorabilia, the complex also includes the home of Miles B. Carpenter, the folk artist who is probably best known for his depiction of the slice of watermelon with a bite taken out of it. Getting closer to Wakefield, the advertisements for the most popular local attraction, the Virginia Diner, get more strident.

The Diner ("The Peanut Capital of the World."™) was established in 1926 when Mrs. D'Earcy Davis served hot biscuits and vegetable soup to hungry customers from a refurbished railway car. I can testify that the Diner's fried chicken and biscuits are wonderful, if stupefying. We turn off the main road at Wakefield and soon encounter political signs planted by various candidates as we approach the Planking in the first volley of what has become known a "sign wars." Last year, would-be Democratic governor Terry McAuliffe erected 25,000 signs extending 20 miles. And he didn't even get the nomination.

The parking is easy, as we are guided into a grassy field by an army of ushers. We relinquish half our tickets. There is a wide path under the trees leading up a gentle hill. Despite a steady drizzle, there's no mud, due to the heavy natural mulch. Between the trees lining the paths and scattered to the right near the crest of the hill are booths manned by various interest groups: Tea parties from Richmond and Hampton Roads, The NRA, Virginia Citizens Defense League, The Libertarian Party.

Governor McDonnell's booth is handing out free beer, Yuengling and Miller. The Sons of the Confederacy are providing serve-yourself beer called Legends. Southern Spirits Distributors provided complimentary mixed drinks of Jim Beam and Red Stag bourbons, as well as Patron tequila.

We immediately come across ex-governor George Allen, who moves easily through the polite, restrained crowd, greeting anyone. His white cowboy hat and boots emphasize the height and size of this former UVA football player.

The crowd reflects the makeup of the booths: white, male, dressed in back-country casual, with a smattering of camouflage attire. Our wives report they have seen three open carries, about a 6 to 1 male-female ratio, and that strangers had tried to pick them up during an unattended moment.

Deep fried shad roe slathered in a dark black peppery sauce are getting handed out. A long shed behind the serving shed holds the planked shad, large fish that have been split and nailed to oak planks and leaned next to a long, smoky oak fire. Someone says they've been cooking there since 5am.

A little after 3pm, the crowd suddenly thins. The food line has opened.

The operation is deadly efficient. The planks of shad are rushed to a large butcher table where Ruritans chop them free of the planks and into serving size. Gray trout, breaded and fried on the spot, are rushed from yet another shed nearby. Another group of Ruritans layers down the meal in strata onto large paper plates: first the baked beans, coleslaw, and shad; then a layer of pickles, then the fried trout, then the corn muffins. Everyone gets the same enormous plate.

A request for "just coleslaw" is met with blank stares and some temporary hesitation in the production line.

We give up the other half of our ticket, grab a sweet iced tea, and are quickly back out in the rain. We find refuge on the windward side of the shad shed. The food is delicious. The smoke gives the shad a mahogany hue, with the same black peppery sauce adorning the roe, the taste is spicy with sweet chunks of meat imprisoned in an astounding number of bones. The corn muffins disappointed, and the shad might have been better if we could have attacked it, firmly seated, with fine utensils– under a strong light.

Just before the formal program starts at 4pm, the rain stops, and the sun tries to shine. After the National Anthem, a prayer, and some introductions, George Allen stands up for this, his third turn as keynote speaker.

Born in California, Allen received a B.A. degree in history with distinction in 1974 at UVA. He graduated from the UVA Law School in 1977. Allen lost his first race for the Virginia House of Delegates in 1979. He ran again two years later, won, and served as a delegate until 1991 when he won a special election for the U.S. House of Representatives in November of that year. Allen was elected the 67th Governor of Virginia, in November 1993; serving from 1994 to 1998. Allen was elected to the Senate in November 2000. He ran for re-election in 2006.

It was during the 2006 campaign that Allen committed the gaffe that may have contributed to his eventual loss to Jim Webb. One day in August, S. R. Sidarth, volunteering for the Democrats, was following Allen's campaign around Virginia. As usual, Sidarth was filming Allen's speech, probably hoping for just such an event. Allen, recognizing Sidarth from previous campaign stops, twice (in what he must have thought a jocular manner) used the term "Macaca" to refer to Sidarth. Macaca is an obscure pejorative epithet used by colonialists in Central Africa's Belgian Congo to refer to the natives. I personally know of no one who has ever heard of the term until then. Nonetheless, it created controversy. After losing the election, he joined the private sector.

George projects an aw-gosh, pragmatic tobacco-chewing good ole boy image. In fact, he has said that his loss for his first try for the Virginia House of Delegates seat was because he was advised to abandon his favored cowboy boot image. I talked to two people who had personal encounters with George while he was living on his farm in Earlysville, outside of Charlottesville, from the '70s to the '90s. Bruce Wachtel, a contractor from Nelson County, did a job on the old building Allen owns across from Lee Park and reported being impressed with Allen: "The man mowed his own lawn."

Fred Gore lived next to Allen's farm in Earlysville for years. He tells the story of how he and his father-in-law went over to Allen's place to complain that Allen's dogs had killed one of Gore's chickens.

"Those aren't my dogs," George Allen reportedly said. "They belonged to my ex- wife. If they bother you any more, just shoot them." But he then graciously compensated Fred for his chicken.

Another time, Gore's two pet Nubian goats escaped. They wandered over to Allen's place where he was having a somewhat formal gathering. When retrieved, one goat was chewing on some ladies hair. George laughed if off, saying it had livened up the affair.

Allen's speech starts predictably by addressing "Fellow Patriots all." He goes on to suggest that a new party be established, called the shad plank party, based upon the acronym SHAD: Smile, Happiness, America, Dream. He jokes that someone in the crowd had suggested that the A stand for Alcohol, but he decided against that. The crowd in front of the stage remains attentive, the crowd in the periphery, however, continues to socialize, creating a slightly distracting buzz. I had the distinct impression that the crowd wanted something more hard-hitting, and that George was deliberately toning down the rhetoric.

The program ends, and Allen was presented with a new compound bow that he posed with. Sign-meister Terry McAuliffe appears and wanders through the crowd. And it was time for us to make our 2 ½ hour drive back to Charlottesville.

The guys in our part pledge to do it again next year. The wives, however, are sure that there'll be something else marked on their calendar on the next third Wednesday in April.

Back in Charlottesville, I speak with Alan Weaver of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Weaver heads up fish passage efforts for the Department and also leads some of the critical monitoring to evaluate the returns of American shad to the James River. He says shad are passing through Bosher's Dam fish ladder, though not in the numbers the Department would like– some years a thousand, some years a few hundred.

Weaver explains that there is an enormous amount of habitat in the James and its tributaries above that dam for these shad to repopulate. He notes that due to lack of funding only the main stem of the James is currently being stocked. He says that they know that some juvenile shad stocked in either the Slate or the Rivanna River have been found back in the James, indicating they have survived at least the first stage of their journey back to the sea. He comments that the Woolen Mills dam removal was not just for shad but helped other native anadromous fish like eels and lampreys.

He says that he is not surprised that we have not seen American shad yet in the upper Rivanna, that at this stage of the restoration efforts "it would be like looking for a needle in a haystack."

I guess I will have to put up my fishing rod for a few more springs, and catch my shad in Wakefield.

~

Author Wick Hunt is a retired Martha Jefferson Hospital emergency room surgeon and shad fan.

A gizzard shad at the Rivanna Reservoir Dam.

Shad Planking 2009: McAuliffe unveils his sign planking.

SCENES:

Former governor George Allen, with compound bow and friend, highlights an assortment of colorful sights.

"Shad-smoked over an open flame, fried fish filet, coleslaw from the Virginia Diner, corn muffins, beans, pickles, iced tea, and plenty of other favorite beverages."

#