Landmark design: County Office Building turns 25

On October 31, county officials celebrated the 25th anniversary of the County Office building on the corner of McIntire and Preston Avenues by christening the $1 million renovation of the 500-seat Lane Auditorium. The auditorium, named in honor of the building's previous incarnation as Lane High School, which closed in 1975, now has new fancy theater seating, a new floor, improved sound and audio systems, new heating and air systems, a partition to create a smaller venue for board meetings, and other long-overdue touch-ups.

For those in attendance, it was an opportunity to reflect on the history of the building and its use as a centralized location for county staff and services for more than two decades. For the rest of us, it's an opportunity to reflect on the evolution of school house architecture, segregation and integration, the modernist movement of the 1970s, and on the meaning of a building we've been living with for so long.

Built in 1939 and named for James Waller Lane, a beloved teacher at the city's first public school who served as Superintendent from 1905 to 1909, it exemplified the style of school house architecture across Virginia at the time.

"They were designed to be landmarks in town," says renowned UVA architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson. "If you look around Virginia, these landmark style school buildings are everywhere."

That changed in the 1950 and 1960s, says Wilson, when the "open plan classroom" theory of education married the minimalist aesthetic of the time. "Schools no longer have that public presence," says Wilson. "Now they look more like shopping malls."

Of course, Lane was also the city's "whites only" high school. Only a few blocks away, in a less prominent location, the Jefferson School served as the city's high school for black students.

In 1956, two years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, a federal judge finally ordered Charlottesville to integrate. That same year, the Virginia General Assembly passed laws as part of its "massive resistence" policy, spearheaded by Senator Harry F. Byrd, encouraging white Virginians to resist integration. Rather than complying with the federal court order, Virginia governor Lindsay Almond ordered the closing of schools across Virginia in 1958, including Lane and Venable Elementary School. According to a Venable Parent-Teacher's Association poll taken at the time, 58 percent of the parents with children enrolled favored integration over closing the school, while 42 percent said the school should close rather than integrate.

However, the "massive resistence" was short-lived. In 1959, after the Virginia Supreme Court declared the massive resistence laws unconstitutional, Almond reversed his position and re-opened the schools, thus beginning the long process of integration.

As Charlottesville resident George Ferguson (whose daughter attended the all-black Jefferson School) recalled in a 1990 UVA oral history project, black students were first put in the superintendent's office rather than in the classrooms, and were not allowed to play sports at the schools they were assigned to.

However, by 1967, when county office associate Diane Mullins graduated from Lane, the school had become fully integrated. As she stands in the hall outside the fourth-floor County Executive's office– one of the few parts of the building unchanged by the 1981 renovation that transformed Lane into the County Office Building– her memories of the old school come alive.

"Quite a few people who work here went to Lane," she says, looking through a tall window on to the auditorium. "I remember dancing on that stage in the senior follies."

As County executive Lee Catlin points out, the building is still referred to as the "old Lane High School" by an older generation, while younger people– and new arrivals– think of it as the place to pay a tax bill, get a building permit, or hold a rally. The Board of Supervisors' meeting room, Catlin says, was the former principal's office, something some older BOS members who'd attended Lane always found amusing.

For Tony Iachetta, who was a County supervisor when the old Lane High School was purchased from the City in the late 1970s, the building was a solution to a problem.

"The County had outgrown its building on Court Square, next to the courthouse," says Iachetta, who served two terms on the BOS between 1975 and 1981. "And there was no way we could enlarge the building."

In the early 1970s, the City elected to build a new high school rather than renovate Lane. As a result, the old school remained vacant for nearly five years before the BOS decided to take a look at it. Iachetta, an engineer by trade, was asked by the board to investigate whether the building was still usable.

"Besides a leaky roof, peeling plaster, and a structural problem with the back stage area in the auditorium," he says, "the building was basically sound."

Iachetta says the County purchased the building– and its 15 acres– from the city for $800,000, a bargain by today's standards. Next, they hired a local architecture firm to spearhead the redesign and renovation, which, according to Iachetta, cost $5-6 million.

Iachetta says he considered the old "industrial-sized factory building" windows on the front of the school– which he says looked very similar to the ones still on the nearby Jefferson School– to be ugly. But not everyone agreed.

According to Wilson, whose has lived here since the 1970s, there was a "big fuss" about the new windows on the front of the building. "They felt it destroyed the continuity of the building," he says. "But I think they ultimately chose that type of window because it was an energy efficiency thing."

UVA architecture professor K. Edward Lay also remembers the fuss. "I do remember the selling of Lane High School to the County," he says. "It was the city's loss and the county's gain. The reduction in size of the windows for environmental reasons was disappointing because it changed the appearance of the facade."

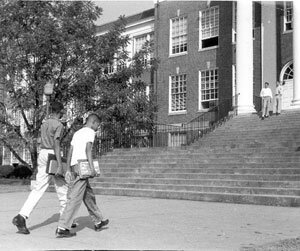

Indeed, a now famous Daily Progress photograph of two black students entering the building in 1959 (see photo insert) captures both the historic moment and the old design of the windows, which appear to be anything but ugly.

Lay notes that the building was designed by Pendleton Scott Clark, a talented Lynchburg architect who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1917.

"Interestingly, an African-American Episcopal chapel had been razed to make way for the school in 1939," Lay says. "They were given a frame church that was dismantled in Palmyra and moved to a site at Grady and Tenth Streets and that served as Trinity Episcopal Church until 1974. It now exists for another denomination."

In 1979, when renovations on Lane began, President Reagan had not yet begun to dismantle his sweater-wearing predecessor's energy conservation initiatives (he eventually had the solar panels removed from the roof of the White House as soon as Carter left office), so it's easy to see why the motivation to make the building energy efficient was still strong.

Still, the minimalist design of the new smaller windows attached to the front and side of the building– which were plugged into the casings of the large, multi-paned old windows using molded panels– must have had architect Clark turning in his grave. Apparently, they are also difficult to open.

Asked about her own desk-side window, Mullins laughs. "Well, it used to open," she says. "But some little mechanism on the side broke." Meanwhile, on the back of the building, nearly hidden from sight, many of the original windows were preserved (the arched windows on the front above the doors were also saved), leading one to believe it wasn't all about conserving energy.

Although county spokesperson Catlin thinks the building has maintained its stature as a center of civic activity, for those who remember, the old Lane High School will always be the soul of the building, when buses pulled up in front of its stately columns, when black children gradually began climbing the stone steps to the front doors with white children, when the grounds teemed with youthful energy, and when the architecture of education occupied center stage in our communities.

Today, the front steps of the County Office Building are rarely used. After 9/ll, says Catlin, the doors were locked as a security measure. Although the grounds in front of the building are sometimes the site of rallies– even a yearly military encampment– the building appears to stare at us as blankly as the WWII memorial out front.

If you look closer and listen, however, you can still hear it speaking. Remember me....

The stately Albemarle County Office Building, which used to be the old Lane High School, recently celebrated its 25th anniversary.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

A now famous 1959 Daily Progress photo of Lane High School captures both an historic moment and the old design of the windows, which were removed when it became the County Office Building 1981.

PHOTO FROM DAILY PROGRESS ARCHIVES

#