COVER- Never mind the iTunes, here's Snocap

Shawn Fanning looked into the eyes of his trusted friends and asked where he had gone wrong. The date was June 4, 2002, and the previous day, the 21-year-old and his music industry-shaking company, Napster, had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, buckling under the weight of nearly three years of litigation. Forced to vacate the company offices elsewhere in the city, he had called his four closest Napster associates to meet in a borrowed San Francisco conference room.

"The mood was definitely somber," recalls Ali Aydar, Napster's senior director of technology and the first employee Fanning hired. "When a company files for bankruptcy, you don't have anything left. I can speak for Shawn and myself and say we had a couple hundred dollars."

But now, thanks to some Charlottesville venture capitalists, they have a new business. It's called Snocap, and like Napster, it might change the multi-billion-dollar recording industry– and perhaps even help the beleaguered industry survive.

The pecking order

After going from the cover of Time magazine to the ranks of the unemployed, the only thing certain for Fanning after the collapse of Napster was that he had found the future of the music business on the Internet. Whether Fanning and his buddies would get a second act was no sure bet on that day four and a half years ago.

"We knew it wasn't over," says Aydar. "We knew we had a good idea."

Over the next eight hours, the five friends hammered out a revolutionary idea: an independent online clearinghouse through which artists and record labels could allow their music to be downloaded over the Internet but still retain their ownership rights.

Nearly 3,000 miles away in Charlottesville, Randy Castleman and Chris Holden were doing some searching of their own. As general partners in Court Square Ventures (along with cell phone pioneer Jim Murray), the two represent a combined 40 years in the media business– and they're always looking for the next big thing in communications technology.

"If we look at a thousand deals a year," says Holden, "we invest in two or three."

And when Castleman met with a colleague in California a year ago, he suspected he might have found a winner. "He told me there was this crazy new music clearinghouse," Castleman says. "It turned out to be Shawn Fanning's company, and it was a sweet spot for what we do. They were at the distinct stage in a company's life cycle where we like to get involved."

Castleman's hunch grew stronger when Fanning and company visited Charlottesville to give Court Square's technology analysts a glimpse of what they had cooking.

"It was breathtaking," Castleman says. "Our team told me, 'It shouldn't be possible to do what they're doing, but they've done it.'"

Today, Castleman represents Court Square's investment on the board of Fanning's new enterprise. He declines to reveal the amount of the investment or to offer revenue projections, but no calculator is required to see that as Snocap begins the process of rolling out its digital wares, it joins a crowded field.

Since Napster's demise, dozens of online music stores have opened along the information superhighway. Almost all work from the same model: they amass a library of music through agreements with record labels, and then allow users to download songs onto computers and portable music players at a price per song.

From Sony's Connect Music Store and Viacom's Urge to Richard Branson's Virgin Digital and Bill Gates' Zune Marketplace, it seems every big name in the biz is trying to turn a profit from Fanning's original idea.

However, these wannabes are like chicks pecking for a single piece of corn compared to the big rooster that is Apple's Steve Jobs. His iTunes Music Store domination of the online music world stems from the popularity of Apple's iPod music player (nearly 70 million units sold to date). Every iPod buyer gets iTunes software and the over three-million-song inventory in the iTunes Music Store– downloadable for 99 cents each.

Apple did not return requests for an interview, but the company reveals that it sold 25 million downloads in the first nine months after its April 2003 launch. In the last nine months, Apple sold upwards of half a billion, bringing the number of total downloads sold to nearly two billion.Such numbers give iTunes Music Store 88 percent of the online music market.

Why do Snocap and its Charlottesville backers think they'll succeed where billionaires Gates and Branson have failed? The same reason Napster set music and digital worlds ablaze in 1999: a fresh idea and a boatload of inventory.

"While it's been proven there's a market for buying music online," says Holden, "there are only three million songs available on iTunes. But there are over 25 million songs out there on the Internet."

According to Holden and Castleman, Snocap's success will come from providing the thousands of unsigned or small-label bands a user-friendly way to sell their music.

"A couple of clicks"

"Once [a musician] comes to our website, they go through a registration process," explains Aydar, the Snocap COO, "and then they're invited to upload their music for free. Once we determine nobody else owns it, we put it into a little store called a MyStore. The whole process takes an hour or two."

MyStore appears on computer screens as a box artists can put on their websites, listing each of their tracks and the price for each song. Snocap takes a 45-cent cut, so any price above that is the per-track revenue to the band. As with the iTunes Music Store, fans can preview any song and buy it via Paypal or a major credit card. Voila! The song downloads to the buyer's computer

"Say you saw a band on Friday and you want to tell your friends about them," Castleman says. "You can go to their MyStore, click 'share this store,' and put the HTML code into an e-mail or on your website, where your friends can buy the music. With a couple of clicks, the artist's fans have just become the artist's sales force."

That combination of user-friendly setup and easy dissemination had Snocap eager to give MyStore a test run with an independent group. So last August they chose the Arizona power-pop outfit the Format as their beta band. Thus far, Format guitarist and songwriter Nate Ruess has been impressed.

"I've heard from our fans about how easy it is to use," Ruess says, "and a lot of them say they've put our store on their blogs."

The Format has sold 1,000 downloads since launching the inaugural MyStore, and now that Snocap has reached an agreement with the popular social networking website MySpace.com (over 115 million members strong and counting), they could be the first of countless bands to profit from the new technology. On Thursday, December 7, MySpace made the MyStore technology available to the more than three million bands who have their own pages on the site.

"This makes a lot of sense for us," says Nate Dominy, bassist for Charlottesville instrumental rock group Gifts From Enola. "If it's that easy, we'd definitely be interested in doing it."

"If you can sell your music and have someone else run the service, I don't see why we wouldn't do it," says Stephen Barling, half of the vocal and cello duo B.C.

"Ten years ago, if you had a friend in San Francisco and you said, 'I heard this local band in a bar, check them out,' forget about it," says Mike Meadows, guitarist and singer for rockers MoneyPenny. "With MySpace, you can listen to any local band in any little town and buy their record. MyStore is another step in weakening the power of major record labels."

It's not just independent bands and mom-and-pop record labels who want in on MyStore. Snocap officials say they're in talks with major labels Sony, EMI, Universal, and Warner Music Group to make their content available through MyStore, too.

"They see see the power of this distinct channel," says Aydar. "They're not taking a wait-and-see attitude."

Court Square Ventures' Holden says that after a decade working for Rupert Murdoch's News Corp. (which owns Fox Television, Harper Collins publishing, and, as of last July, MySpace) to protect against piracy of the company's materials, this marks a significant breakthrough.

"Old media that have fiercely protected their content for 100 years," Holden says, "now own new content and are learning how to let go of it in order to profit. Old and new media are finally meeting, and Snocap is becoming part of that process."

One element critical to the evolution of "new media" is the online journal known as a blog. From the Internet-generated hype surrounding this year's surprise hit movie Snakes on a Plane to the "Macaca" video that changed the course of Virgina's senate race, blogs can spread information around the world and become a powerful media force.

Snocap hopes to use the so-called "blogosphere" to bring music to fans.

"It's a better alternative than just posting the song and having to worry about the legal implications," says UVA fourth-year John Ruscher who operates a music blog called NailgunMedia.com. "If a lot of bands sign up for this, it could work pretty well."

UVA second-year Derek Davies, who runs another music blog, goodweatherforairstrikes.com, sees a similar dynamic. "It's within reason I could use this on my site," he says. "I'd be interested to see how well MyStore catches on in the industry before I make a decision to embed it in my posts. But it's a brilliant idea in principle."

Even some companies that already offer downloaded music are welcoming Snocap. That's how Jim Kingdon, director of merchandise for Crozet-based MusicToday, sees it.

"The more music gets to fans, the more they can determine they have a connection to that artist," he says. "The greater that connection, the more fans are going to want to go to concerts and to the artist's official site to engage in that relationship."

Kingdon's company is so enthusiastic that it's offering prizes (including studio time with noted producer Bruce Flohr) in an online battle of the bands– a competition for downloads launching in January (and sponsored in part by the Hook).

So with unsigned artists, major label power players, bloggers, and even competitors bullish about Snocap's prospects, is there anyone to doubt the new company's inevitable success? Oh, yeah.

Free for all?

If first-hand research is an indicator, Snocap's greatest potential obstacle just might be the very demographic they hope to recruit as loyal customers. Last week, the Hook invited eight high school students to a demonstration of Snocap's MyStore.

All eight admit they have downloaded music illegally from Napster-like file-sharing networks such as LimeWire and Kazaa or from a friend's computer, usually as an mp3. The mp3 is universally playable, unprotected by copyright– and it just so happens to be the format in which MyStore sells music.

Seven of the eight say they get their music almost exclusively via free mp3s. Only one out of eight has ever paid to download music.

"It's just easier to get when you get it on LimeWire," says Rusty.

"When you can get it for free, paying for it seems kind of ridiculous," says Sarah.

"The last music I bought was the Spice Girls when I was six," says Belle.

The group reviewed both the Format's own MyStore and a blog-embedded MyStore where the band is selling tracks for 79 cents. Any chance the students would purchase mp3s that way?

"If it's an indie band I liked that nobody really knew about," says Hayden, "I'd use this to buy their music, because this is really easy. It's going to be really expensive if they get big, and I can always say I liked them before anyone else."

"Yeah, I guess if I really liked them," says Rusty, "I could say I helped make them big."

Other responses were cooler.

"If I couldn't get their music from someone else," says Hunter.

"I guess if it's my favorite song," says HaNee, "but if I had some other way of getting it, why would I pay?"

Sorry, Snocap brass.

And what of the new idea: being able to send friends MyStore in an e-mail?

"If I just paid for it, why would I make my friend pay for it?" asks Sarah. "Why wouldn't I just send it or burn it to a CD?"

"I guess I might put MyStore on my MySpace page or my Facebook [another online social network] profile," says Hunter, "but if my friend is sitting right next to me, I'll just send him the mp3."

Of the eight students interviewed, seven say they'd simply send the mp3.

Hearing such unpromising feedback, Aydar admits that illegal downloading is likely to continue to be a fact of life. But he still thinks there's enough profit to be made selling music by the download to make it worth doing.

"I think a lot of the reason why that behavior exists is that there hasn't been, thus far, an experience that allows consumers to find any content they can conceive of," says Aydar. "Once you provide that, people will get used to it, and behavior will change."

With the project in final countdown on the launch pad, the San Franciscans and Charlottesvillians are betting the event will mark the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the music industry and of the Internet: the Snocap era.

"It comes down to the philosophical question of 'Do you think people are going to do the right thing?'" says Castleman. "If you put up walls, you're squelching the consumption. You'll make more money if you go out there and say, 'We're selling this music; we think this is a fair price.' On balance, people will do the right thing."

If they're wrong to gamble on a new technology and people's virtuous impulses, it will mean one more music download service has bitten the cyberspace dust.

But if they're right, it could mean more than just huge fortunes for its principals, and perhaps even more than a new beginning for the music industry. It could mean a fundamental change in the way the media do business. It all depends on whether music fans are willing to start whistling a new tune.

Behind these walls, Court Square Ventures are quietly helping to plan what might be the next big thing in music.

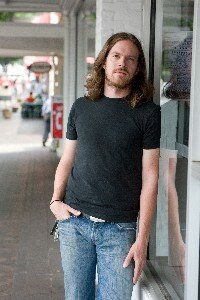

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Shawn Fanning created the file-sharing network Napster in 1998 when he was a freshman at Northeastern. Eight years later, he came to Charlottesville and persuaded Court Square Ventures that he had created a way to assure the music is legitimately sold.

COURTESY OF SNOCAP

"Without getting into specifics, I can say that all the major label groups are very positive about this," says Ali Aydar, Napster's first hire and chief operating officer of Snocap.

COURTESY OF SNOCAP

"The MyStore is another step in weakening the power of major record labels," says MoneyPenny's Mike Meadows.

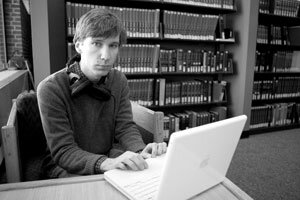

FILE PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Music bloggers will be key to the success of MyStores. John Ruscher of NailgunMedia.com says, "If a lot of bands signed up for this, it could work pretty well."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Will teenagers buy into MyStore the same way they flocked to MySpace? One focus group is less than thrilled with the idea.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

#