COVER- You've got male: New school says boys will be... separate

Name some Little Rascals. Alfalfa, Spanky, Buckwheat. If Darla or Mary didn't make your list, that may be because the boys– rowdy, hyper, messy– took center stage. But a new school aims to show that boys, since they're different from girls, can thrive in an environment that caters to them. And to them only.

"Something is happening where boys are getting the message 'School is not for you,'" says Todd Barnett, founder of Field School of Charlottesville, an all-boys middle school set to launch this fall. Barnett acknowledges that boys can be rambunctious, but he says forcing them to sit for seven hours at a desk, and prohibiting horseplay– even at recess, as some schools do– is counterproductive.

Among signs of problems in schools: the number of boys medicated for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); boys' disproportionate disciplinary issues compared to girls; and the widening achievement gap between boys and girls, as evidenced by the fact that girls now make up nearly 60 percent of the incoming classes at many universities, including UVA.

A growing body of research suggests that single-sex education– even in public schools– may allow students of both sexes to excel academically and socially in ways they don't in coeducational settings. Indeed, a UVA study published in 2003 in the journal Psychology of Men and Masculinity found that boys who attended single-sex schools were more than twice as likely to pursue interests in art, music, drama, and foreign languages as boys of comparable ability who attended coed schools.

In traditional education settings, "what we often end up doing is suppressing boys' normal emotional development," Barnett says.

But is single-sex education all it's cracked up to be?

A boy crisis?

Over the last decade, numerous books and magazine articles have detailed an almost desperate situation for boys. Michael Thompson's book Raising Cain, shot to best-seller status by alleging a failure of mainstream educators and parents to meet the needs of boys and provoking a crisis of depressed, underachievers more likely to drop out of school and to have difficulties forming emotional connections.

Mainstream media took notice. Newsweek's January 30, 2006 cover story, "The Boy Crisis," questioned whether the high divorce rate and lack of fathers in boys' lives contributes to the problems. And the May 26, 2003 cover story in Business Week, "The New Gender Gap: Why boys are falling behind girls in education," concluded that the reason so many boys are not achieving their potential is that "educators lost sight of the learning style of boys" and that "educators also haven't done nearly enough to keep up with the recent findings in brain research about developmental differences."

Among the findings: that the testosterone a male fetus is exposed to in utero permanently "masculinizes" the brain. In the book Why Gender Matters, author Leonard Sax details those differences: the areas in girls' brains that control language develop before the areas that control geometry, while the opposite is true for boys; girls process emotion in the same area of the brain where language is processed, while boys process language and emotion in different areas of the brain; boys learn better than girls in stressful situations; and– perhaps most strikingly– girls' hearing is as much as seven times more acute than boys' hearing, suggesting that boys who appear not to be paying attention to the lesson may simply not be hearing it.

These are elements that Barnett– who taught for several years at Maryland's Landon School (yep, all boys)– plans to address with the Field School. Already, many Charlottesville families know him as the director of the seven-year-old Field Camp, a popular co-ed summer camp program.

At the proposed school, since many boys have difficulty sitting still, there will be ample physical activity, including an emphasis on after-school sports and two recesses each day for all grades. All that, Barnett says, will not detract from a rigorous academic curriculum, including literacy, math, history, geography, and Latin.

Barnett– who has worked on the school for a year– now has a prominent partner in the effort: Corey Harris, the W.C. Handy-award winning blues phenom. While most people know Harris for his musical accomplishments, he also has a degree in linguistics from tiny but prestigious Bates College in Maine, was the recipient of a Watson Fellowship, and taught for a year in New Orleans in the 1990s. He was recently notified that he'll receive an honorary doctorate in music from his alma mater in May before gearing up to teach Latin at Field as well as running the school's art and music program.

"He's the kind of guy you just can't pass up," says Barnett.

Harris, dad to two children– a 16-month-old girl and a second-grade boy, and stepfather to a fourth-grade boy– says he was looking for a way to cut back on his touring and spend more time with family.

"I don't feel like I want to spend the next 15 years traipsing the globe," says Harris. "I've accumulated a lot of experience, and I feel it's time to share it with kids– not just my own, but others'."

Both Barnett and Harris say research is increasingly showing that single-sex education is particularly beneficial during the critical middle school years when puberty strikes and social pressures can distract from academic pursuits. In a co-ed setting, Barnett says, boys are more willing to participate in activities that might be considered girl-centric. At Field School, for example, Barnett plans to have a boys' choir in addition to the sports. "We're going to sing every morning," he says.

Lots of interest

At a recent Field School informational gathering at Barnett's downtown apartment, he and Harris are eager to share their enthusiasm. Before approximately 20 people– many of them prospective parents and their sons– the two break into a surprise a cappella performance of the new school song, penned, appropriately, by Harris. The parents are listening to the music– and the message.

"I think it's a more difficult time in a child's life," says Tim Gable, whose rising fifth-grader, Ethan, will join the Field School in the fall. Gable says the decision to enroll Ethan is based in large part on the high regard he has for Barnett, who has run Field Camp, an outdoor adventure program, for the past seven years. Ethan agrees.

"He always has something to say that's educational," says Ethan, before scampering into another room to play with a group of boys engaged in a jumping contest that involves crashing into a wall.

Gable says Ethan– currently attending Hollymead Elementary– spent much of third grade reviewing first- and second-grade material in preparation for the state's Standards of Learning tests, or SOLS. "While repetition is good," Gable says, "it's not good when you're learning the same thing again and again."

Gable says Barnett's emphasis on nature and physical activity is a huge draw. "Schools today," he says, "are pulling back on that for fear of lawsuits from injured kids."

The good feelings may be contagious at the introductory meeting, where Barnett and Harris charm the crowd, and several board members are on hand to answer questions. But not everyone in attendance is convinced.

"I think we've decided to stay with the public school system," says Peter Weems, a retired minister whose nine-year-old son, Caelan, attends fourth grade at Charlottesville's Venable Elementary.

Weems, who says he's still willing to consider Field School, says he's had to push to keep Caelan challenged and interested at Venable. And while he says there are gifted teachers in the public schools, he's worried about sending his son to Walker Upper Elementary. "We keep hearing great things about Walker," says Weems, "but there are no men over there."

With Barnett and Harris as the primary instructors, boys would have at least two male role models at Field.

Weems, who says he "loves the whole attitude" of Field School, is not put off by the $8,500 tuition– thousands less than other area private schools' tuition. But he says he has some concerns about enrolling his son in a start-up venture. "My great fear is that the curriculum would be kind of thin," he says.

That perception doesn't surprise Barnett. To allay such worries, Barnett says he will base his curriculum on that of the all-girls Village School in Charlottesville and even plans to use many of the same materials. And while the schools are not officially affiliated, Village School co-founder Proal Hartwell sits on the Field School board for support and advice.

Is co-ed really bad?

It's easy to get swept up by the latest research, and all parents want the best for their children. But are all the boys who remain in co-ed settings doomed to a life of failure and loneliness? One recent report says no.

In June, the Education Sector, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, released a report saying boys are doing just fine in traditional, coeducational settings. Among signs of their success: improved test scores and increasing numbers of boys going to college– and then graduating.

Despite all that, the report acknowledges that girls are still ahead.

"The real story is not bad news about boys doing worse," the report says, "it's good news about girls doing better."

At the city's Walker Upper Elementary, there actually must be at least one key man: principal Jim Henderson. He says he believes the real factors behind students' success are a top-notch staff and a rigorous curriculum. In addition, he says having a diverse student body– in both gender and race– is a positive.

"We're engaging our students in social responsibility," says Henderson, "helping them make good decisions with the opposite sex, with different races, and treating all people cooperatively and kindly." Learning to interact with students of the opposite sex is an important educational goal, he says.

And Mary Riser, head of middle school at St. Anne's Belfield, agrees that keeping the genders separate is not the key to a good education.

"What students need most in the classroom is to be well known and to receive thoughtfully planned instruction," says Riser. "At St. Anne's Belfield, our small class size allows teachers to pay attention to the specific learning needs of all children, both boys and girls."

Barnett acknowledges that single-sex education isn't for every student, but he believes it can be beneficial to many boys and girls, particularly in middle school. He worries that the Education Sector report did not look at all the elements of a successful education, and he points to the fact that UVA– once a bastion of male education– now has a nearly 60 percent female student body. Encouraging all boys to achieve their potential is his goal, he says.

As noted, Field School won't be Charlottesville's first experiment in single-sex education. For the last 12 years, the Village School on High Street has provided single-sex middle school education for girls.

Village School co-founder Jamie Knorr says one aspect of single-sex education that's helped Village is that's it's allowed students to take "risks." He cites the open sharing of ideas in class– including reciting of poetry– as examples of things girls might have more difficulty with in a mixed-gender classroom.

"In a single sex environment, there's more freedom to be expressive. There are fewer distractions," he says.

Eighth grader Tara Riccio agrees. She says she's loved her years at Village.

"You get to know people easily and end up feeling comfortable around them," she says. "I think that at an all-girls school, there's obviously a lot less distraction, which is good."

But that's not to say she isn't excited to mix it up in high school. "I am looking forward to going to a co-ed school again," she admits.

Tim Gable is hoping his nine-year-old son will be as happy at Field School next year as Riccio has been at Village School.

"Todd's really doing it as an extension of what he is– genuine and honest. He brings the inner man out of a boy," Gable says. "He finds who each one is and doesn't treat children like numbers on a clipboard."

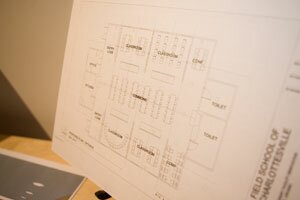

Barnett says he's close to finalizing the school's initial location, which will likely be in the Claudius Crozet Park community center in Crozet. He proudly shows architectural renderings of the space, which will feature flexible classrooms with moveable walls and a large central common area. The school is accepting applications for the fall for 16 spots in each the fifth and sixth grades. (Seventh and eighth grade will be added over the following two years.) A shuttle will take students from Charlottesville to and from school each day.

The school's board of six members is working on raising money to fund scholarships to help increase diversity, and Harris will perform a benefit concert at Starr Hill on April 24. On February 20, Field School is teaming with Woodberry Forest to bring Raising Cain author Thompson to Lane Auditorium for a speaking engagement. Field School board member Walker Richmond, a local attorney who taught for six years in the '90s in a boys preparatory school in Boston, says he's optimistic about the school's future.

"Todd has this fantatstic experience and awesome enthusiasm that he's really going to bring to this place." Richmond says.

While he attended co-educational public schools and remains a proponent of public education, Richmond says he believes single-sex education in middle school is worth the effort if it helps foster a boy's love of learning.

"If you lose a kid in sixth grade," he says, "that can have huge ramifications down the road."

"We're going to sing every morning," says Field School founder Todd Barnett, left, singing the new Field School song penned by Corey Harris, right.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Crozet Park

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

The new school will feature flexible space.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Board Members Isabel McLean, Walker Richmond, Mimi Pohl, Todd Barnett, and Corey Harris.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

#