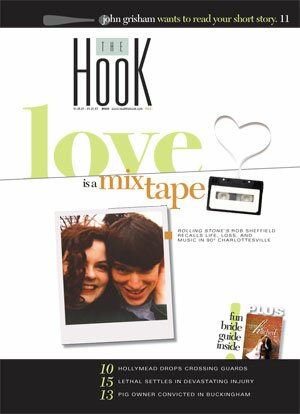

COVER- <i>Love Is a Mix Tape</i>: <i>Rolling Stone </i>writer on love and loss in Charlottesville

The two nationally known, Charlottesville-based rock critics were so inseparable that someone thought they were one person. But May will mark 10 years since the two were separated by death. Now a new memoir by the survivor, Rolling Stone rock critic Rob Sheffield, remembers the mysteries of love, life, and music in Charlottesville in the 1990s.

We go together

Rob Sheffield and Renée Crist were two people, but not everyone realized it. "Our friend Suzle told me her sister didn't understand," Rob writes. "She always thought Suzle had one friend named 'Robin Renée.'"

"I couldn't imagine Rob and Renée apart," says Chuck Taylor, general manager of indie radio station WTJU where the couple volunteered. "It was clear they really were enthralled with each other."

In December 2002, when Sheffield, a contributing editor at Rolling Stone, was moving into his new apartment in Brooklyn– over five years after Renée had died– a box of old cassette tapes sparked a memory of his late wife.

"I spent an evening putting all these mix tapes onto shelves and listening to them," says Sheffield. "It helped me make emotional sense. It made everything really vivid, immediate, dredging up pleasurable and painful memories with the same song."

That first all-night listening session led to many more, and he decided to use 15 of the tapes as the basis for the 15 chapters in his first book, Love Is a Mix Tape. Published this month, the memoir tells the story of Rob, Renée, and a third character who introduced them and gave them a home: a mutual friend named Charlottesville.

I saw her standing there

Like a lot of great love stories, this one owes its start to serendipity. In this case, a gangly Irish Catholic boy from Boston via Yale, and a pint-sized Baptist girl from Pulaski County via Hollins College happened to be in Eastern Standard restaurant (now Escafé) sipping bourbon on September 17, 1989.

Sheffield had originally planned to keep his relationship to Charlottesville strictly one of host and guest.

"I moved to Charlottesville for grad school with my plans all set," he writes. "Go down South, get my degree, then haul ass to the next town. The South was a scary new place. The first time I saw a possum in my driveway, I shook a bony fist at the sky and cursed this godforsaken rustic hellhole."

But that night at Escafé convinced Sheffield that Charlottesville had more to offer than exotic wildlife. And the right tape just happened to come on the house stereo.

"The bartender put on Big Star's Radio City," writes Sheffield. "Renée was the only person in the room who perked up. We started talking about how much we loved Big Star. It turned out we had the same favorite Big Star song– the acoustic ballad 'Thirteen.'"

It turned out they had a lot more in common. Both were at the University of Virginia pursuing masters' degrees from the English department (he for an MA to eventually become a professor, she for an MFA to become a fiction writer); both were fans of college radio bands like the Replacements and the Meat Puppets. Fortunately– but unbeknownst to Rob– Renée had just broken up with her boyfriend that night.

On November 20, 1989, the night before Renée's 24th birthday, the two officially became a couple and kept coming back to the restaurant for more bourbon and Big Star.

"It was a place the MFAs hung out because the music was good," Sheffield says. "I was with the critics, and she was with the writers. The writers were just more fun."

In July 1991, less than two years after that first chance encounter, "Robin Renée" were back in Eastern Standard, sitting at the bar, staring at their bourbon-and-gingers, talking pop culture. A few hours earlier, they had been at the Best Western on Emmet Street dancing to "Thirteen" for their first dance as husband and wife.

Subterranean homesick blues

If getting comfortable in their Downtown home away from home came as naturally as making mix tapes, life in their actual home, Renée's apartment near Buford Middle School, wasn't static-free.

"It would flood when it rained really hard," says Sheffield, "but they fixed that toward the end."

Floods or no, there were still the problems of the mold the floods left behind, lack of air conditioning in the humid summer months, and upstairs neighbors who skipped out on the electric bill, sparking a two-week power outage. Not to mention that one pack rat now had to make room for another's collection of records, books, and Red Sox memorabilia.

"It was crammed with this cache of popular culture," recalls friend Karl Precoda. "You had to party very sedately in that house."

But party Rob and Renée did, hosting regular gatherings where they served their trademark purple cocktails of Zima and Chambord in the summer. It was in social settings like these that the contrast between the introvert and the firebrand came into sharp focus.

"Some of us are born Gladys Knights, and some of us are born Pips," explains Sheffield in the book. "I marveled unto my Pip soul how lucky I was to choo-choo and woo-woo behind a real Gladys girl."

Those who attended their parties had no trouble telling who the frontwoman was, but that didn't mean the other half of the duo wasn't part of the show.

"If you met the two of them, she would be the one doing the talking," remembers friend and fellow WTJU DJ Gate Pratt. "He would be the kind of guy to stand off to the side and watch, but she would bring him out."

"Rob pulled back a little bit, not that ready to share everything, but once you got him talking, you found he he could make a case for the band Boston being fantastic," recalls Precoda, who was a guitarist for '80s avant garde rockers the Dream Syndicate. "But if Renée liked something, she wanted you to like it, and she'd bug you about it. With both of them, it was cool to see that kind of enthusiasm."

Turn your radio on

That insatiable desire to share the music they loved led Rob and Renée to freelance as critics and reporters for influential music mags like Rolling Stone, Spin, and the Village Voice when they weren't working odd jobs around town

At home, Dave Matthews Band was building a national following, but Rolling Stone's "Sheffield Report" (with a silly cartoon likeness of Rob) was more likely to spotlight indie rockers than fraternity favorities.

For her regular "Tüne Town" column in C-Ville Weekly, Renée went so far as to offer band-specific fashion and beverage tips for concerts (attending the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion show at Trax on December 11, 1996 meant wearing bellbottoms and drinking "all of it"). She did so under the nom de plume of "Jo Cline."

"At the time, there was the controversy over Joe Klein from the Washington Post being the anonymous author of Primary Colors," explains Sheffield. "She liked how it sounded like a girl's name and how she could spell it like Patsy Cline."

But while the written word might have helped pay the rent, the couple's favorite medium for spreading the gospels of Yaz, Pavement, Marshall Crenshaw, and hundreds of other favorite artists remained the transmitter for 91.1 on the FM dial, WTJU.

Between Rob and his Wednesday 2pm show "Description Without Place" or Renée's Thursday 2pm program, "Ground Rule Double Dutch," Charlottesville listeners were guaranteed four hours of midday rock 'n roll from two of its biggest fans (who just happened to be two of America's top music critics).

"You couldn't help but enjoy yourself listening to them," recalls WTJU's Taylor. "Even if you weren't crazy about the music, you could tell everyone was having a good time."

According to fellow WTJU DJ Tyler Magill, Rob and Renée succeeded in exposing listeners to new music while steering clear of any notion of being hipper-than-thou.

"With both Rob and Renée," he says, "there was a sense of, 'We have this secret club, wanna join? It's really fun!'"

Just as in life, Magill says they each had a distinct radio personality.

"Rob was low key, just like he's talking with friends, just dishing about cool stuff," says Magill. "Renée was very peppy, happy, with this great, resonant voice with a hint of an accent."

And sometimes those who dropped by the studio at UVA's Peabody Hall during Renée's show would get to see her exhibit another skill.

"Every few months, I'd come in," Magill says, "and she'd already have newspaper laid down. She'd put on 'Common People' by Pulp, which is six minutes long, and give me a perfect haircut by the time the song was over."

Why was there such good humor between between WTJU's DJs and the listeners? Sheffield says it had as much to do with the listeners as it did the "talent."

"The passion for music in the air in Charlottesville is amazing," he says, "so being able to play music for people who were into music that intensely was an honor and a pleasure."

That relationship even got to the point of DJs being able to identify listeners by the songs they requested.

"Every year, we did a David Bowie marathon," says Sheffield, "and every year one woman would call and request the demo version of 'Candidate,' which is a rare song that's available only as a bonus track from Diamond Dogs. So every year, we'd say, 'I can't wait until the 'Candidate' lady calls!'"

Sheffield says other 'TJU DJs and listeners were responsible for shaping his musical tastes in the '90s.

"Listening to Chuck [Taylor], I'd get exposed to all this psychedelic music from Buffalo Springfield and Ultimate Spinach and all these other bands I didn't know existed," he says. "So I would play those bands on my show, and someone would call me up and say, 'You should play Moby Grape' and I'd check them out."

But much as Sheffield enjoyed the synergistic education at WTJU, he still says there was no better way to check out new music in Charlottesville than heading down Ivy Road for some sushi.

Ma vie en Rose

New York had CBGB in the '70s, Athens had the 40-Watt Club in the '80s, and if ever there was a place to check out the latest underground music in mid-'90s Charlottesville, Sheffield says, it was Tokyo Rose.

Attracting everyone from Charlottesville's Curious Digits to Melbourne, Australia's Dirty Three, the sushi bar/basement rock club had a reputation powerful enough to lure even the most jaded indie rockers.

"Bands told me they would go out of their way to play there because Darius [Van Arman, who booked bands for Tokyo Rose and was unavailable to be interviewed for this piece] had a reputation as a stand-up guy and the audiences were so into it," says Sheffield.

"So many shows that went down there that it was just ridiculous," says Chris Hlad, the venue's former house DJ. "You'd leave that club feeling not just entertained, but empowered."

Even when the "power to the people" vibe was in short supply, Karl Precoda recalls that Rob and Renée were always good for a smile.

"There was a band I used to see there called Spbgma," the influential guitarist says, "and every time they were there, Renée would elbow me in the ribs and say, 'Look! They're copying you!'"

While such a remark might get a chuckle, the man who could be counted on for a guffaw and a song was Tokyo Rose's owner and sushi chef Atsushi Miura.

"On a good night," writes Sheffield, "Atsushi would close the sushi bar, come down with his acoustic guitar and play his original Japanese ballads. He also sang some tunes in English like 'I Hate Charlottesville' which always ended up being a big sing-along."

Good natured wisecracks between regulars were usually par for the course, but nobody was joking about the band on the night of April 5, 1996, when punk's once and future queens Sleater-Kinney stormed Tokyo Rose with what Sheffield calls "an all-time, split-the-world-in-half punk rock show."

"It was one of those moments where you could feel the whole crowd explode in the first song," he says.

"I remember one girl threw her bra onstage," says Hlad, "and it caught [guitarist and lead singer] Corin Tucker's mic stand and she let it hang there the whole show."

"Then [guitarist] Carrie Brownstein pipes up and says, 'I want one!'" says Sheffield. "From the first note on, we knew nobody would forget that one. I interviewed the band years later, and they hadn't either."

So unforgettable was the show that Rob and Renée made sure to buy tickets to Sleater-Kinney's May 25, 1997 return to Tokyo Rose as soon as they went on sale, sure that the show would be as memorable as the first. For those who attended, the second show is even more deeply burned into memory than the first. But tragically, the reason was one nobody could have imagined.

One more hour

As he recounts in his book, at 3pm on May 11, 1997, "Renée stood up, took a step, and then suddenly fell over onto the chair by her desk."

Moments later, an EMT told Rob, "We're taking her to Richmond for the autopsy. It's standard procedure when somebody so young dies."

The coroner in Richmond explained to Rob that a blood clot from Renée's leg had gone through her bloodstream to her heart, and that even if it had happened at a hospital, there was nothing doctors could have done to save her. There was no medical explanation except that she was "just unlucky."

With her death, Sheffield writes, "Robin Renée became Rob and Renée."

"I was a wreck," says Magill. "We all were."

"The fact that it happened that way was very much a shock," says Hlad. "It was a tragic thing in the true sense of that word."

"It was a heartbreaker," says Precoda.

"I was at the funeral," says Taylor. "I don't want to talk about it."

Renée's funeral was on Thursday afternoon, her radio time-slot, at Fairlawn Baptist Church in Pulaski County. Sheffield calls the day "a blur," though the music is still vivid in his memory.

The only song at the service was Renée's favorite hymn "Shall We Gather at the River," but the song stuck on repeat in Sheffield's head was Sleater-Kinney's "One More Hour."

"Corin Tucker sings about how she has to leave in one more hour," he writes. "The guitars try to hold her in check, but she screams right through them, refusing to go quietly because it's already too late for a graceful exit. Corin snarls and she stalls, all for a little bit, just a little bit more time."

Not two weeks after the song played its endless loop in Sheffield's head, Sleater-Kinney returned to Tokyo Rose.

"That was the first show where a lot of people went out again," says Magill. "That was a cathartic experience."

Sheffield, mourning alone, didn't attend that show or any others in those days, but he sometimes looked for relief on the airwaves.

"I was driving to a memorial concert for Renée, listening to WTJU, and I heard them play 'Thirteen' by Big Star," says Magill. "I started to flip out. I went to the station, and they said Rob Sheffield had called and asked them to play it."

The beat goes on

Sheffield writes that after three years he began to think about moving away from the town he'd shared with Renée: "Charlottesville was always going to be her place. I wanted it to stay that way."

He found his new home in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint in 2002, but soon found the pull of Hookville to be stronger than he'd anticipated.

Sheffield says writing Love Is a Mix Tape forced him to look back at Charlottesville in a way he hadn't been able to since Renée's death. "It was like walking into rooms I had sealed off," he recalls. "Sometimes it was just devastating, but the more I wrote, the more I wanted to share it with people."

In particular, Sheffield wanted his book to reach other young men who had lost their wives.

"I was conscious in writing the book that I had been so hungry to read something like this when I was going through it," he says. "There's such isolation that comes with being a young widower, so I hope this can be of some strength or comfort."

Charlottesville's pull on Sheffield wasn't limited to literary abstract. Soon after moving to New York, he returned to Charlottesville to visit friends and met another WTJU DJ whom he first heard on the air doing a Pixies marathon. "DJ Astrogrrrl" was Ally Polak, a UVA astrophysicist, and on December 30, 2006, she and Sheffield married in New York.

He won't say how his new wife feels about his literary tribute to Renée, but in the "Acknowledgements" section he writes, "All love and worship to Ally Polak. None of this could have been written without her love and support and feline soul."

If a November trip back to Charlottesville is any indicator, Ally fits right in with the friends Rob and Renée shared.

"We went to Baja Bean with Tyler," says Sheffield. "They set up the karaoke, and it turned out they had this amazing selection."

"I did a Blur song," says Magill, "Rob did 'Do You Remember the First Time?' by Pulp. Ally did Depeche Mode, 'Master and Servant.'"

Says Sheffield, "It was an 'only in Charlottesville' moment."

He says that after his almost two decades as a music journalist, a song can still affect him on a emotional level, even when the singer died before he owned a radio.

"This summer I was on 250 East," he recalls, "and Jim Croce's 'I Got a Name' came on the radio. This is a song I'd heard a million times before, but this time I had to pull over because I was crying because I missed Jim Croce so much. I'm sure it annoyed the other drivers, but there I was in the breakdown lane, singing 'I Got a Name.'"

Sheffield says that when he's not writing his "Pop Life" column for Rolling Stone, he still returns to Charlottesville "three or four times a year." While the increasing number of "really ugly, cheesy subdivisions" and "friends getting priced out of town" has surprised him, there's a core feeling that hasn't changed about the city he and Renée knew.

"What's still the same is that Charlottesville is a magnet for crackpots of various kinds," says the man who launched a national writing career from Smallville.

"It's the kind of place where you can be a crackpot in your own way, and people are fine with it," he says. "Maybe that's why there are so many music freaks."

Rolling Stone contributing editor Rob Sheffield chronicles the eight years he spent in Charlottesville with his late wife, Renée Crist, in his new memoir, Love Is a Mix Tape.

COURTESY OF CROWN PUBLISHING GROUP

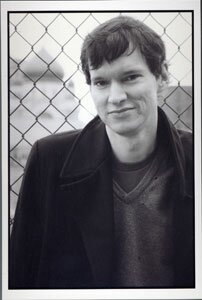

Tyler Magill still DJs on WTJU as co-host of Sunday night's "Radio Wowsville." Sheffield listens to the show online from his Brooklyn apartment.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Sheffield was a DJ at WTJU from 1994 through 2000. Of his behind-the-mic experience, he says, "being able to play music for people who were into music that intensely was an honor and a pleasure."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Both Rob and Renée occupied the WTJU DJ chair for two hours a week during the mid-'90s.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Back when it was called Eastern Standard, Escafé was where Rob Sheffield met Renée Crist. The bartender had put on Big Star's Radio City album, and, according to Sheffield, "Renée was the only person in the room who perked up."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Tokyo Rose was the site of many of the best times Sheffield shared with his wife, including a particularly raucous (and lingerie loosening) set by the riotgrrrls in Sleater-Kinney on April 5, 1996.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Rob and Renée mugging for the camera in Lee Park in the spring of 1993 when they were 27

COURTESY OF ROB SHEFFIELD

#