Do we desire a streetcar?

Carting a Styrofoam cooler– like the ones that carry hearts to be transplanted– the post-doctoral researcher startles me by hopping on the Charlottesville Free Trolley near the University of Virginia hospital. Seeing me eyeing her cargo, the 30-ish woman explains in a cheerful British accent, "not organs, just blood samples. I'm delivering them after lunch."

A couple of stops later, she disembarks near a restaurant, and a dozen stops after that, the Trolley returns downtown to Live Arts where my bicycle and I had climbed aboard 48 minutes earlier. In between, driver Chuck Fix has picked up and dropped off 21 riders during a UVA holiday.

"It's sometimes standing room only," says Fix, while waiting near the Rotunda to ensure he doesn't get ahead of the planned 45-minute roundtrip. "The mornings are super busy when classes are in, and traffic can be a big, big issue."

Then he adds, "Charlottesville has needed a bypass for 10 years, and I understand it'll be another 10 years before we get it."

And therein lies the rub.

In America's auto-saturated culture, even mass transit drivers think the solution to congestion is building more highways– even if the highway doesn't connect to the downtown gridlock– while a European researcher trusts mass transit enough to cart perishable medical supplies around on a Trolley.

***

My 48 minutes on the free Trolley are not particularly important, except that with global warming and "peak oil" fears approaching the boiling point, some Charlottesville area planners are considering creating a regional transit authority and possibly tearing up the Trolley route to run a modernized– and environmentally friendly– electric streetcar down West Main Street.

Like the 29 bypass, the streetcar– if built– is perhaps a decade in the future, and that's if federal funds for alternative transportation don't dry up during the current state and local stampede to deal with a looming oil shortage.

With Americans driving about 2.9 trillion miles every year, this country hasn't met its own oil demand since 1971 and– at $60 a barrel– has been spending about $250 billion overseas annually to import the black gold that fuels nearly every aspect of our economy– most notably, the single-occupancy automobile.

Spurred by the international perception that America is in Iraq for its oil as well as the popularity of Al Gore's global-warming documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, counties and cities are falling over themselves to develop fast, convenient, and reliable alternative transportation.

Charlottesville's start may not be so impressive. In Virginia, Williamsburg, after 15 years of seeking federal dollars to build enabling infrastructure, boasts the largest number of people biking to and from work. And while Loudoun County has apparently accepted gridlock as a fact of life, Arlington has made strides fostering dense development around transit.

Compared to these initiatives, a plan to replace Charelottesville's three free Trolleys between the Downtown Mall and UVA's main grounds with streetcar track may appear to be a drop in the bucket. But it's a key drop, according to several regional transportation plans and international transportation expert Peter Newman, who spent last semester as a Fulbright scholar at UVA.

Acknowledging that no one knows how to best transform Charlottesville, Newman has some succinct advice: "Just start. Be conceptual. Recognize your opportunities and grab them. As long as you start, you can find your way through." [Newman has a thoughtful essay on the back page of this edition of the Hook– ed.]

Finding a way through Charlottesville traffic is becoming more and more difficult, according to many observers. But the growing frustration might just serve to spur new ways of thinking about transportation.

"The main issue for me is 20 years out," says former Mayor Maurice Cox, the streetcar's biggest backer. "We have to think long term. The traffic in the core is already unbearable, so the quality of life we associate with Charlottesville is already significantly eroded."

Congestion caused by single-occupancy vehicles is, indeed, the most noticeable result of America's love affair with the automobile. The famed Texas Transportation Institute doesn't keep numbers for Charlottesville, but it notes that in 2003, drivers across the nation spent three times as many hours stuck in traffic– an average of 47– as they had in 1983. In one year, the Institute claims, drivers lost 79 million more hours and wasted 69 million more gallons of fuel to congestion.

The key word is "more." Until America embraces old-fashioned mass and muscle-powered transportation, almost every transportation planner in the country believes that each year we'll spend more of our national wealth importing ever-scarcer oil to produce more miles-driven-per-capita and spew more CO2 into the atmosphere to produce more global warming. It's such a lose-lose-lose situation that few politicians will even consider addressing it.

Republicans and Democrats agree on raising money to build more roads– from Governor Tim Kaine to the recent GOP transportation deal allowing Northern Virginia to tax itself to the tune of $383 million annually. And yet the state's 1998 Commission on the Future of Transportation in Virginia declared that building roads creates more– not less– congestion, a phenomenon called "induced demand."

Induced demand is a theory bolstered by lots of recent evidence, most notably a 1980s beltway around London. The theory suggests that building more auto infrastructure to ease the hassle of driving ironically causes more people to drive further and more often– and gobble land for far-flung developments. So besides creating rather than curing congestion, new roads may actually destroy any hope of reducing America's greenhouse emissions or our daily burn of 19 million barrels of oil.

"Congestion increases as people move outward from urban centers, and additional lane miles of roads to accommodate the people lead to more development, and more people, and more congestion, and more lane miles– and around it goes," the Commission reported. "Urban planning experts say it's a futile exercise to attempt to build your way out of congestion problems by adding more highways."

According to a 2002 study by the locally based Southern Environmental Law Center, Virginia lost 68,700 acres to development each year during the late 1990s, the equivalent of a 188-acre farm lost each day. The acceleration of land consumption is so strong that the Richmond area, for instance, doubled its footprint of developed land between 1992 and 1997, while that region's population increased just eight percent.

But although most transportation economists agree that a serious gasoline tax is needed for both energy security and environmental health, when gas prices spiked nationally last summer, congressmen from both parties suggested that Uncle Sam should rebate our national 18.5 cents-per-gallon gasoline tax.

With so-called "soccer moms" in SUVs considered the key swing voters across the country, no candidate can challenge America's passion for automobiles. Instead, blame lands on everyone else, as a January neighborhood transportation meeting full of angry Charlottesville residents illustrated.

Prompted by UVA computer professor John Pfaltz, approximately 20 citizens– primarily female and white– gathered at a church on Cherry Avenue to consider what might be done about the over-crowded roads in their front yards.

Several blamed UVA for allowing students to bring cars; a few called for the closing of Old Lynchburg Road at the city line; and others wanted more law enforcement to catch out-of-area drivers. But everyone pointed a worried finger at what's happening on the streets they drive each day.

Jeanne Chase, for example, complained that rush hour begins on Old Lynchburg Road at 4:45am and "Things finally quiet down at 2:30am."

Chase is clearly worried about the 31,000 daily car trips projected for the über-development Biscuit Run community. "The county's impacting the city big time," says Chase, "but they're not coming up with the bucks to alleviate the traffic they're creating."

Actually, the County does pay ten cents of every $100 in assessed property value to the City under the 1983 annexation-barring Revenue Sharing Agreement. But although most of the people in any new county suburb will work and shop in Charlottesville, City voters get no voice in whether Albemarle develops at an unbridled pace or pursues a smart-growth agenda.

Meanwhile, there's no national policy to reduce auto dependency. Taxing fuel in one state creates an incentive for drivers to simply cross the state line for cheaper gas. Even Loudoun County claims it's unfair to raise taxes solely in Northern Virginia to address its overdevelopment, and 55 percent of Northern Virginia voters said no to a 2002 referendum that would have increased the sales tax a half-cent to pay for new roads.

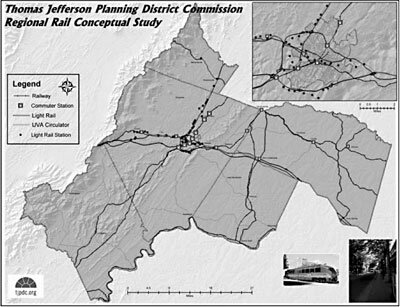

Harrison Rue, Thomas Jefferson Planning District's executive director, argues that our area's first step is creation of a regional transit authority that would include the County in ownership of the Charlottesville Transit Service and then, in the best of all possible worlds, lead to routes that might put some rush back in rush-hour.

Recognizing that closing roads just moves drivers to other roads while doing nothing to help the environment, and that very little space exists to build additional in- and out-bound roads, Rue was pushing for $200,000 to study transit opportunities. He got part of his wish in late January when the Metropolitan Planning Organization voted unanimously to ask Charlottesville and Albemarle to ante up $50,000 each to match a possible $100,000 Virginia Department of Rails and Public Transportation grant.

"What I've recommended is that we try to do this work in a way that will potentially qualify us for federal and state funds," Rue says. "Transit always is an uphill battle. We're not quite as advanced as other states in realizing how transit gives people real choices in how to get around. But a regional strategy is critical to making a downtown system work."

Unfortunately, even a joint County-City transit service leaves out the 22,000 commuters who arrive daily from Nelson, Greene, Fluvanna, and the other counties. But the possibility of a West Main streetcar might itself ease some in-bound commuting issues.

"We would have more people carpooling, maybe taking the bus or whatever downtown, if we had a convenient, fast and dependable way to get them around the city once they're here," Rue explains. "The good news is that we're trying to coordinate the streetcar task force with the work of the regional transportation authority."

Nationally, critics of such transit systems have had a field day, blasting their high costs– which in Charlottesville could be $10 million to $15 million per mile– as tourist gimmicks. Some wags have even suggested that buying each user a limo might cost less.

While such suggestions might veer toward hyperbole, local critics raise several issues of their own. Pfaltz and North Downtown Residents Association President Colette Hall wonder why planners would consider laying tracks in the one place where the bus system seems most reliable.

Hall worries that streetcars could harm bike lanes and reduce parking spaces– two reasons her Association opposes the streetcar system.

"And the third reason," says Hall, "is that one of our goals is underground utilities. We used to have so many big, beautiful trees in Charlottesville that have been cut back and killed to protect the wires. Now we have very narrow sidewalks with a lot of intruding utility poles. People want to be pedestrians and want underground wires, but we'll see more [streetcar] wires overhead and more ugliness reaching out to the side of the road."

Pfaltz, who promotes a bicycling city, wonders why the streetcar isn't planned out Jefferson Park Avenue to Fontaine Research Park and the new developments at the county line. Ditto for Preston and Grady Avenues and then north into Barracks Road Shopping Center.

"I don't see what it buys going down Main Street," says Pfaltz. "It's going from nowhere to nowhere, and it's going where the Trolley already goes. But if it went to Barracks Road Shopping Center, that would be a reasonable transfer point between a BRT [Bus Rapid Transit] coming down 29 North."

Former mayor Cox, however, is adamant that the West Main route is "fundamental" to restoring Charlottesville as a "walkable, lovely community.

"In part, you have to follow the path of least resistance," says Cox, an architect and urban planner at UVA. "Preston is no one's idea of a pedestrian corridor. It might have potential, but not for starting right now. The pressure's on West Main Street. It's going to develop whether we like it or not, and Main won't develop to its best potential without transportation.

"The streetcar is a really good excuse to make great urban places. If you look at the work from around the world, it's about the place– it isn't about the streetcar– about dynamic urban places that people want to hang out in, and moving people from one great place to another."

Alia Anderson directs the non-profit Alliance for Community Choice in Transportation, which has been a prime mover behind the streetcar discussion, and she backs Mayor Cox's concept of "place."

"That's the core of the proposal, economic vitality," says Anderson. "Rail transit all over the world has proven to be a tool for re-investment, infill, and encouraging mixed-use development. It adds walking and biking and all of the things that produce the vitality of a downtown."

But, after my Trolley trip, I biked to a handful of West Main businesses, and none could envision much positive effect from 2.5 miles of streetcar track running down the key route to their parking lots.

Mel Walker of Mel's Diner, whose mother fondly remembers the old West Main streetcar, predicts no plus or minus effect on the Diner. "If people want to eat here, they'll always find a way," he shrugs.

"I think it's ridiculous," says Kay Allison, owner of the Quest Bookshop, "I can't see any economic impact, and I really can't see how this short route would serve the majority of the people of Charlottesville."

That, says visiting scholar Newman, is the reason why selling transit is "always a fight." Americans are so used to cars that transit-oriented development is outside our mental boxes.

"Start where the most need is," Newman says, "and then go to a series of connecting points, so at some point in the future along all the highways you should be able to get to transit and get where you're going quicker than by car."

The streetcar envisioned for Charlottesville would not only have its own lane free of automobiles, it will be able to electronically change stop lights to ensure it stays on schedule. Some Bus Rapid Transit systems also have light priority, but they enjoy protected lanes only in a couple of cities around the world.

Furthermore, after studying transportation in 100 world communities, Newman says that buses just don't create development the way rail does. But once it starts– as has happened in Tacoma, Washington, and Portland, Oregon– the value of land along the rail increases an average of 15 percent as people surge into the shops, businesses, and apartments near the stops.

"City council could un-fund the Trolley in a heartbeat, the bus line in a heartbeat," says Cox. "But once those tracks are laid in the ground, since the streetcar is faster than the cars, it's a major project to move them. So people who are thinking of moving, of buying [along the line] will buy with an assurance that that line is going to be there forever."

What's not going to be here forever, as a new group called Charlottesville Peak Oil claims, is the gasoline and diesel to run our single-occupancy vehicles. Like global warming foes, Peak Oil members worry that without planning and action today, this nation's economy will collapse when Venezuela and the Arab states cut the 12 million barrels of oil we import daily, or when international regulation finally caps America's annual spew of 1,959 million metric tons of transportation-generated CO2.

Long-time Charlottesville bicycling activist Alexis Zeigler believes that if we don't "think globally and act locally" today, we're literally dooming our way of life. "Hopefully, we can begin a purposeful contraction rather than be forced into a non-purposeful contraction that ends in totalitarianism," Zeigler says.

"We have a huge amount of energy, but we're using it really stupidly," Zeigler continues. "There's a huge case of denial among Americans about where our freedoms come from and what peak oil and the other constraints are going to do to our democracy."

In November, the City created a Streetcar Task Force, and the group's report is expected in June. But public participation and understanding are key.

"The more information, the better the conversation and the better the feedback," says Brian Wheeler of growth watchdog group Charlottesville Tomorrow. "The more informed the voters are, the better everything is."

In an attempt to address global warming and peak oil, Senators John McCain and Barack Obama support a bill calling for a personal "cap-and-trade" carbon program that would demand that citizens emitting above a specific level of carbon dioxide purchase the right to emit that extra pollution from people below that specific level.

If this bill eventually passes, drivers without transportation choices will personally face the high cost of oil depletion.

Randy Salzman is a former communications professor and now a Charlottesville-based freelance writer.

DATAPOINTS SCATTERED THROUGH STORY:

• Over the past 25 years, Americans' vehicle miles per person have risen an average 6.3 percent, eradicating any environmental or energy gains from the sale of higher-mileage cars. America today has 226 million cars, more than the number of drivers.

• American transit riders are already the most subsidized in the world. About 2/3 of most transit systems' budgets come from state, local and federal taxpayers.

• While producing 33 percent of our greenhouse emissions, transportation contributes less than 11 percent to Gross Domestic Product.

• Annually, America consumes 26 percent of the world's oil but has only five percent of the world's population and 2.7 percent of the world's oil reserves.

• America imports over 11.5 million barrels of oil a day. With transportation consuming 13 million barrels, we use about 19 million daily overall.

• A 2004 rail study by the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission scolded UVA for building its 12,000-employee capacity Research Park north of the airport without making provision for a rail connection. "Given that a highway lane can only handle about 1,500 passengers per hour (in single-occupancy vehicles), this means that if all 12,000 people commute up from Charlottesville within the same hour, then eight northbound highway lanes are required in the morning and eight southbound lanes in the afternoon."

• Americans make 411 billion trips a year, about 87 percent in an automobile, and burn some 163 billion gallons of gas and diesel.

• Some 54,500 citizens commute around Charlottesville and Albemarle. Another 22,000 drivers arrive from outside the county while about 4,000 leave daily. Some 78 percent of Albemarle commuters drive alone, while 61 percent of city commuters use single-occupancy vehicles.

• With China's importation of oil expected to climb to 14 million barrels a day by 2025, OPEC – in which nine of the 11 countries are Muslim – has other potential markets for oil. Hugo Chavez has Venezuela's six Citgo refineries up for sale and promises to play his "strong oil card" against the "world's roughest player, the United States."

–datapoints compiled from various economic books and newsmagazines and Department of Transportation, Energy Information Agency, Geologic Survey, and Thomas Jefferson Planning District reports."

Regional planners envision light rail as far west as Crozet, as far north as Stanardsville, and as far east as Zion's Crossroads

THOMAS JEFFERSON PLANNING DISTRICT

The Hardware Store restaurant closed December 30, but the building might be on a streetcar line

OKERLUND ASSOCIATES

Should we rip up the Trolley route for a streetcar system?

Thomas Soloman, Maurice Cox, and Pete O'Shea

Maurice Cox: "If we don't have foresight; what is going to ensure the quality of life in this city?'"

#