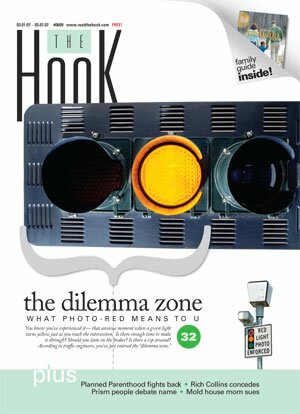

COVER- Dilemma zone: Are red-light cameras the answer?

You know you've experienced it– that anxious moment when a green light turns yellow just as you reach the intersection. Is there enough time to make it through? Should you slam on the brakes? Is there a cop around? According to traffic engineers, you've just entered the "dilemma zone."

Now imagine the intersection is equipped with a single-shot camera ready to snap your picture the second the light turns red, or with a video camera recording your every move from approach to stop (or dash). According to critics of automated enforcement technology, now you've entered the twilight zone.

In a strikingly safety-conscious legislative session– which included House passage of a measure to require booster seats for children up to eight years old– the General Assembly passed legislation allowing the use of cameras to nab red-light runners at intersections. Such traffic cameras, which have been in use for about a decade, snap photos of red-light runners' license plates, and a ticket is automatically generated.

By installing these cameras, local governments across the county are taking an unprecedented step: allowing machines to issue traffic tickets. And there appears to be local support for the new technology.

"We've been supportive of this legislation for a number of years," says Albemarle County spokesperson Lee Catlin. "We would be very happy to have this option available, especially for major intersections like Route 29 and Rio."

"I fully support the use of these cameras as an effective way to reduce intersection accidents," says Charlottesville Police Chief Tim Longo, adding that traditional red-light enforcement has always been problematic, raising safety concerns for both drivers and officers. Indeed, County Lt. John Teixeira, who also supports the use of the cameras to reduce accidents, says it's "almost impossible" to enforce red-light violations at intersections like Route 29 and Rio because officers can't safely pursue offenders through the intersection.

Of course, no one likes red-light runners, and everyone wants safer intersections. But are red-light cameras the answer?

Ironically, just two years ago, the General Assembly declined to reauthorize a 10-year red-light camera pilot program after a VDOT study showed an overall increase in accidents at intersections with the cameras. In addition, a 2005 Washington Post investigation into the effectiveness of D.C.'s red-light cameras, which were installed in 1999 and 2000, found no noticeable difference between the number of accidents at intersections with cameras and at intersections without them. Worse, the investigation found that accident rates at intersections with cameras had actually doubled since 1998.

It seems that red-light cameras, while they may slightly reduce more deadly t-bone collisions, actually increase the number of rear-end collisions, as people frantically brake to keep from getting a ticket.

"The data are very clear," said Dick Raub, a senior researcher at Northwestern University's Center for Public Safety who reviewed the Post's findings. Intersections with cameras, he said, "are not performing any better than intersections without them."

In a five-part 2002 series on use of red-light and speed cameras in the District of Columbia, an exhaustive investigation by the conservative Weekly Standard called the automated enforcement technology the "baldest cash grab by cities since they sued gun manufacturers for making guns that shoot people." At the time, D.C.'s red-light cameras had netted $15 million in a little over a year, and its speeder-catching cameras had hauled in over $9 million in just seven months.

In fact, in the first eight days of photo radar use, 23,418 motorists were photographed for potential violations, compared to only 10,000 tickets issued by D.C. in all of 2000. By 2004, the report concluded, D.C. could realize $117 million in fines.

In addition, the report showed that claims about cameras making intersections safer were questionable at best, and that simply increasing yellow-light times was a more effective way to reduce red-light running. Indeed, in 2005 when VDOT increased the yellow-light time by only 1.5 seconds at US Route 50 and Fair Ridge Drive in Fairfax– an intersection with a camera under the pilot program– it resulted in a 94 percent drop in citations.

Nationally, only about 800 of the approximately 42,000 annual traffic fatalities are caused by drivers running red lights. Yet communities across the country have spent millions on these camera systems in the name of safety. In addition, according to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data, red-light running and speeding pale in comparison to the use of alcohol and a "failure to keep in proper lane or running off the road" as factors that lead to fatal crashes.

Here at home, according to 1998 DMV data, only 3.3 percent of all crashes involved people who ran red lights. And in Charlottesville, according to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data, there were just four intersection or intersection-related fatalities between 1997 and 2005, compared to 10 blamed on "roadway departure," nine characterized as "single vehicle" and 11 as "non-junction fatalities" (meaning not at intersections or crossways).

While these statistics offer little consolation to people who've lost someone in a traffic fatality– and they are among the most impassioned supporters of red-light cameras– they seem to argue against red-light running as a major safety concern.

Red-light camera use presents a host of legal problems as well. In 2001, a San Diego lawyer successfully had 300 red-light tickets thrown out because a judge agreed the machines were fundamentally unreliable, a decision that has led to similar court cases across the country. The cameras also can't determine who's driving the car, meaning the owner is presumed guilty until proven innocent, a situation that had the ACLU cautioning against the technology, and that could potentially clog the courts with people claiming they weren't driving when the cameras caught their car.

Because of the uncertainty over who was at the wheel, most states don't assign license points to people who get camera tickets, California and Arizona being the exception. Several other states are flirting with the idea.

As the 2005 VDOT study points out, the Code of Virginia requires the delivery of an in-person summons to compel an individual to appear in court. Theoretically, the study suggests, unless red-light camera citations are hand-delivered, they could become "essentially unenforceable."

And, of course, any time technology is used for enforcement, people tend to develop technology to counter it. Already companies sell license plate covers that may make it impossible for red-light cameras to decipher them, and Global Positioning Systems can alert a driver when intersections with cameras are near.

More frighteningly, some theories suggest that red-light cameras can be defeated by driving so fast through the intersection that the camera misses the shot, a method one can imagine being irresistible to risk-taking teenagers. Apparently people can also develop considerable resentment toward the devices. Across the country, despite such cameras being installed in bullet-proof casings, they're often pelted with rocks, spray-painted, or smeared with colored lubricant. In Paradise Valley, Arizona, according to the Weekly Standard's report, one disgruntled driver shot 30 rifle rounds into two photo-red cameras.

Slippery-slope concerns are warranted as well. As the ACLU points out, "Government and private-industry surveillance techniques created for one purpose are rarely restricted to that purpose."

In France, Germany and England, for instance, where police began using red-light and speeding-ticket cameras in the late 1980s, the technology evolved to include 24/7 video surveillance cameras on street corners. Once cameras are installed in Virginia, what's to keep them from being used to gather other information?

The evolution

Sponsored by Chesapeake-based Republican John Cosgrove, the camera law began as House Bill 1778, and passed the House on February 6 by a vote of 63-35. On February 20, the Senate version passed 30-10.

Charlottesville-area Democratic Delegate David Toscano voted for it, while usually law-and-order Republican Rob Bell, who dislikes the presumption of guilt aspect of the technology, voted against it.

But does the technology really work? Are officials exaggerating the threat and overselling the technology? While no one can deny the cameras identify red-light runners, a mountain of evidence suggests they don't significantly make intersections safer, and that simply increasing yellow-light times is a more practical solution.

According to former House Majority leader Dick Armey, a Texas Republican who launched a campaign against red-light cameras when he was in Washington, it's all about the revenue. Armey says the "red-light running crisis" started about the same time (about 20 years ago) that the federal government started issuing guidelines to cities suggesting they shorten yellow-light timing.

"Of course, these changes were made in the name of safety," Armey wrote in a 2001 Washington Post op-ed. "But... the policy of shortening yellows has been a complete failure. Intersections are less safe as a result. Nonetheless, many within the transportation bureaucracy cling to reduced yellow times because it's extremely profitable."

As Armey explained, when drivers aren't given enough yellow-light time, it becomes more difficult to make the right decision. Indeed, in the 1970s, the Institute of Transportation Engineers began recommending that yellow-light times be increased to allow for "clearance time"– how long it takes a driver to cross an intersection– and were still recommending the change in the late 1980s. However, by the late 1990s, yellow-light intervals had been reduced by as much as a third, creating the condition that caused traffic engineers to coin the term "dilemma zone."

But instead of simply experimenting with longer yellow-light timing, the transportation bureaucracy embraced camera technology as a solution, a technology that has the potential to generate even more revenue than short yellow-light times. Indeed, as the cameras in D.C. have shown, there are millions to be made. The companies that manufacture and operate them– most notably Affiliated Computer Services, which bought the technology from Lockheed Martin IMS a few years ago, and which owns and operates about 80 percent of the cameras in the country– pocket considerable revenue as well, as the devices average about $50,000 each, with another $5,000 to $10,000 more for sensors and installation. In many jurisdictions, camera manufacturers also process the tickets and receive a percentage of the fine.

"The reason that states push the cameras rather than engineering solutions is the money," says National Motorist Association spokesperson Aaron Quinn. "The cameras bring in money while engineering solutions like lengthening yellow-light time cost money."

However, as Armey points out, Fairfax reduced red-light running by lengthening yellow-light times. And he cites the experience of Mesa, Arizona, where adding one second of yellow-time to several intersections led to a 73 percent drop in red-light running. Armey issues a practical challenge to communities considering red-light cameras: "Increase the amount of yellow time you provide motorists, and watch what happens."

As Albemarle's Catlin and Teixeira point out, the intersection of 29 and Rio is one of the places where cameras might be installed. However, as a Hook video on our website shows (you can see it at: www.thehook.net/2007/02/26/web-advance-are-red-light-cameras-the-answer/ ), the light at the intersection of 29 and Rio routinely turns yellow before the second car in line at the stoplight crosses the intersection. Around 9:10am on February 12, when a reporter visited, a car ran a red light on each of the five light changes we monitored. In one case, a school bus was in the intersection when the light turned red.

"It's a rather short cycle at that intersection," says VDOT spokesperson Lou Hatter, explaining that VDOT traffic engineers use a standardized formula to calculate yellow-light times (between three and six seconds), and that all lights in town operate on a computerized system. Hatter suggests that shorter yellow times have more to do with managing the flow of traffic than generating cash flow.

"Short green cycles at intersections like Rio are the result of trying to keep traffic moving on 29, especially after they synchronized the lights," says Hatter, adding that even the smallest time adjustment on the lights along 29 could snarl traffic. "Remember, it's a major highway."

Although Hatter says he's not aware of any data that would suggest longer yellow-light times make intersections safer, he seemed open to the idea and expressed concern that lights were turning red on drivers crossing 29 at Rio.

Of course, camera supporters have their own data to prove that red-light cameras work. But it comes almost exclusively from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), the industry group best known for crash-testing new cars at a facility in Ruckersville.

Recently, in a nod to Armey's yellow-light argument, an IIHS study conducted in Philadelphia found that red-light violations decreased by 36 percent when yellow-light times were increased, but by 96 percent when cameras were added, prompting IIHS senior engineer Richard Retting, a figure as ubiquitous in the red-light camera debate as Armey, to declare victory for red-light cameras. There was, however, no emphasis on the increase in rear-end crashes after installation of the cameras, or the statistically small number of fatalities caused by red-light running. Nor was there any mention of the aforementioned legal or practical problems with their use, or any conclusive data that actually proves the cameras make intersections safer. In fact, the study, as all red-light proponents do, exaggerates the safety concern by declaring the 800 yearly fatalities caused by red-light running alarming.

"These statistics only suggest that there is a problem with red-light violations across the country," says Quinn. " The solution isn't cameras though, it's improved traffic engineering."

On February 20, while the Virginia Senate was debating the bill, Senator Kenneth Cuccinelli (R-Fairfax) tried to amend it by requiring localities to lengthen yellow lights. The proposal was killed.

"There's no inherent enforcement in traffic signals," says VDOT's Hatter, acknowledging that the safety of intersections always has depended, and still depends on human judgment. "It's basically an honor system."

But if red-light cameras come to Charlottesville, that honor system could be a thing of the past, replaced by the judgment of a machine. And as considerable evidence suggests, it may be the less honorable system.

Smile, you're at the intersection of 29 and Rio: County and City officials cite the Rio/29 intersection as a candidate for a red light camera. However, as a Hook video shows, it may just need a longer yellow light. To see the video, CLICK HERE.

The Gatso gets you: the infamous Dutch-made Gatso photo-radar camera has been nabbing European drivers since the late 1980s.

PHOTO BY ANDREW DUNN

This sight in Springfield, Ohio could be coming to an intersection near you.

PHOTO BY DEREK JENSEN

Film speed: This image shows what drivers in Germany get in the mail when they get nabbed by a photo-radar speed camera.

AUTHOR UNKNOWN

#