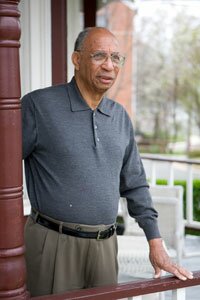

COVER- Tectonic shift: Eugene Williams loosens his tie

As a youngster growing up in Charlottesville during the Depression, Eugene Williams lived a block from one of Charlottesville's best neighborhoods. His father was a gardener, and their house had a beautifully landscaped yard. But unlike the fine houses owned by white people on Ridge Street, the Williams home on Dice Street did not have indoor plumbing.

Disparity in real estate has been a recurring theme in Eugene Williams' life. In 1980, he decided to do something about it.

He had a vision: Purchase 21 dilapidated, rental properties– many of them historic– scattered throughout the city, renovate them, and rent them to provide decent, affordable housing to low-income tenants. By scattering such subsidized rentals, tenants could avoid the stigma of being in "the projects" and become more economically integrated into existing neighborhoods.

It was a reversal of the then-popular "urban renewal" strategy of tearing down slums and herding all the poor people into one location. The federal government was starting to get the message, but even before the 1983 creation of the "Section 8" voucher program, the Williams family began trying to make subsidized housing work for Charlottesville.

Twenty-seven years later, Dogwood Housing is closing its doors, and the company has put its 21 properties on the market. With Charlottesville real estate soaring, there's little question the properties will sell. Whether they will continue to house Section 8 tenants, however, is another matter.

The McCreary properties

"I thought it was crazy." That was Lorraine Williams' reaction when her husband proposed sinking their life savings into the 21 rentals from the estate of the Reverend E.D. McCreary Sr., a Baptist minister, for $325,000. And Eugene Williams wasn't just risking their own funds– he wanted his brother and sister-in-law to cough up major chunks of change as well.

"It was a shock," says Albert Williams, Eugene's younger brother, who, with his wife, Emma, was being lobbied. "We didn't have that kind of money and didn't believe it could be done.

"After we recovered, we went along with it," remembers Albert, 78, a retired music teacher in White Plains, New York. "He kept calling it a 'diamond in the rough.'"

After the initial surprise, none of the family members doubted that Eugene could pull off the scheme without losing everything. "I thought it would work if he was doing it," says Lorraine.

Her confidence in Eugene's abilities was shared by others who would be instrumental in raising the funds Dogwood Housing needed to renovate the properties and provide Charlottesville citizens with 62 affordable rental units.

"Back in those days, we had a lot of ghetto housing," says former mayor and delegate Mitch Van Yahres, who had tried to get some of that housing condemned when he served on City Council in the '70s. "Eugene came in and put in affordable and livable housing. That was impressive. We'd seen some horrible, horrible places that were Third World."

Then-city planning director Satyendra Huja was on board from the start. "It was significant because it was 62 units," says Huja. "Number one, we got low-income housing. Number two, we got housing fixed."

Huja worked with Williams to get credit, and the city put up $200,000 to guarantee the loan. "It was unprecedented to guarantee a private developer," says Huja. "I don't think we'd done that before or since."

Frank Buck, who was mayor at the time, had already crossed paths with Eugene Williams, who has long been a fierce critic of city government, having fought public housing as far back as the 1960s.

"Where Eugene and I developed a high degree of trust was over the city's flower program," Buck recalls. "Eugene pointed out– 'Look at where you have them: in affluent, white areas.' He said, 'Take a look at Meade Park or Tonsler.' There wasn't the equity that should have existed."

Buck conceded the point. "His criticism was correct," says Buck. "Thank God for the Eugene Williamses to keep us pretty honest."

So when Williams approached Buck with his plan for affordable housing, it wasn't a tough sell.

"I thought he could pull it off because if you know Eugene, he's a man of a lot of integrity and a clear vision of what housing should be for minorities," says Buck. "He's a person of high standards. He was taking housing that was in bad shape and upgrading it. That was an easy decision for us."

Buck offered Williams the use of his law office in the evenings to work on the project. The city extended repair times on code violations, and the Virginia Housing and Development Authority qualified the tenants for rent subsidies.

Still, the biggest hurdle remained: finding $1.4 million in loans to rehab the rentals.

"It was pretty difficult," says Bonnie Smith, then a loan officer with a bank that eventually became part of Bank of America.

Her reaction upon hearing Williams' plan? "Oh, really. Oh, my. I don't know if this is doable, but we're certainly going to try because what he wanted was worth the effort."

Any renovation can uncover hidden problems. "This was not just one house," says Smith. "It was several." The bank also was concerned about the Williams brothers experience in buying and renovating property. While they'd purchased apartment units in 1960 on West Street and refurbished them, they'd never done anything on this scale before.

And at that time interest rates were pretty high. "We ended up doing a tax-free bond deal," recalls Smith.

"Eugene was very persistent," she says. "He got it done on budget– that was even more extraordinary."

"Some people helped him just to get rid of him," laughs Williams' younger brother.

Eugene Williams hired unemployed tenants to help contractors do the work. And although he offered subsidized housing, that didn't mean just anyone could live in his units. For Williams, unemployment was a temporary condition and accepting welfare was not a permanent career path.

Finally the renovations were complete. "Rental property is only as good as its management," observes Smith, "and he truly managed that property."

And he has continued to do so. Albert Williams says he suggested winding things up a decade ago, but were it not for the fact that Williams is now 79, he says, he'd probably continue to manage Dogwood Housing.

They might be glad they waited. Charlottesville real estate values have experienced double-digit annual increases for at least the past seven years. The properties purchased in 1980 for $325,000 are now on the market for a cool $7.9 million

"We were never trying to make money– never," says Albert. "We never lost sight of what we were trying to achieve: good living conditions for the underserved."

Seeds of Dogwood Housing

From the very beginning, racial discrimination was a fact of Eugene Williams' life and one that he's never ceased struggling against.

Besides growing up in a house with no indoor plumbing a block away from one of Charlottesville's swankiest neighborhoods, he had to walk past the segregated Midway High on Ridge Street, where Midway Manor is today, to reach Jefferson School for black children. And UVA, which wasn't integrated until 1950, was not an option for either Williams brother.

"Where did [Dogwood] start?" asks Williams. "With my mother and father having so much pride."

Their mother worked as a domestic– one of the few jobs available to African American women– seven days a week, with a half day off on Thursday and Sunday. And their father, who meticulously landscaped the yard around their house, died when Eugene was 10.

In 1953, Williams started selling insurance for the black-owned Richmond Beneficiary Company. That job gave him freedom that most African Americans didn't have at that time– the freedom to speak out.

"Your voice can be larger," his daughter, Scheryl Glanton, notes, "when you're not financially dependent on those who may not want you to have a larger voice."

In 1954, Williams became president of the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and membership that year grew from 65 to 900, and to 1,500 the next. He fought to desegregate the schools, and Lorraine, a teacher, joined a lawsuit against Charlottesville City schools.

When a federal court ordered black students to be admitted to Lane High School and Venable Elementary in 1958, Governor Lindsay Almond closed the schools for five months rather than comply, a dubious chapter in local history called massive resistance.

"When Brown v. Board of Education came out," says Eugene Williams, "it didn't mean school boards across the country said, 'How do we comply?'"

And once those schools reopened to admit black students, it didn't mean the struggle was over. It took another lawsuit to enable then third-grader Scheryl Williams to attend Johnson Elementary in 1960– with a police escort.

Eugene Williams organized sit-ins to desegregate restaurants where blacks were not allowed to dine, and he wouldn't allow his children to go to movie theaters where African Americans were expected to sit in the balcony.

Scheryl Williams Glanton remembers many a Saturday as a little girl, sitting in at the Woolworth's lunch counter wanting a fountain shake that would not be served to her because of the color of her skin.

Even after the more blatant discrimination ended, Eugene Williams continued to be outspoken about more subtle slights. And that's why he saw the purchase of the McCreary properties as the answer to a dream he'd had since the 1960s, and a way to disprove popular stereotypes about blacks.

"For example, we've always thought that if blacks move into a neighborhood, that causes it to become blighted and property values to go down," says Williams. He cites the example of Ridge Street, the location of some of the Dogwood properties. Once all white, it became all black, and is now integrated.

Property values in the city have continued to go up, including in racially mixed neighborhoods. "At least we've shown there is no truth to such a myth," says Williams.

Better people

"He encourages his tenants to better themselves and get in a position where they can buy their own homes," says Carolyn Shears, whose Summit Reality is handling the liquidation of Dogwood. "I can't think of another landlord in Charlottesville who does that."

Decent housing was just the first step. In the course of fixing one of the rentals 27 years ago, a plumbing problem left the kitchen floor wet and dirty. Williams asked the tenant for a newspaper to put on the floor, and he was surprised the tenant didn't have any.

"Instantly I thought, with no reading material in the house, what hope did she have to improve and be informed?" says Williams. "I decided to find a way to put reading material in tenants' homes."

Thus was born Informed People Are Better People, the monthly newsletter of Dogwood Housing. The first page, "Thoughts," is an essay followed by a news article Williams thinks will be interesting to his tenants.

"At first it wasn't accepted as I expected," says Williams. "After a short time, tenants began to look for it when they came to the office to pay the rent."

Today Williams notes with pride that Dogwood Housing rentals are integrated by class, income, and race, and all are rented at market value. For example, one house includes a Section 8 apartment, and two others occupied by a university grad student and a university professor, all rented at fair market value, says Williams.

He keeps an album of before and after pictures– the blighted houses Dogwood Housing purchased and the maintained residences they are today.

As Williams shows a reporter some of his properties around 10th and Page streets, a neighborhood known in the recent past for gunfire and drug dealing, he counts the seven new houses valued at $250,000. And he credits the Piedmont Housing Alliance, a quasi-public body, for investing in upgrades and rebuilds in the struggling neighborhood.

He points to an "under contract" sign on 10th Street. "That just went up last week," he says. "I get excited when I see those signs."

Hortense Cruz has lived on Page Street for six years, and she says Williams has "helped me very much." Cruz has a neurological condition that prevents her from working, and she moved here to find a one-level house that's close to the doctors at UVA Medical Center.

"Now the neighborhood is good," says Cruz. "When I first got here, there was vandalizing and shooting. Now it's nice."

Cruz has a very real concern about the liquidation of Dogwood Housing, should its new owner or owners decide to abandon Section 8 housing. "I don't have any other place to go," she says. "I'm worried that the rent could go up. I receive Social Security."

Williams reassures her that she has a lease. But after the lease expires, whether Cruz will be able to keep her house will be out of his hands.

"We've gotten a lot of inquiries from people who share Mr. Williams' same vision," says Shears at Summit Properties, "but it will be a market-based decision."

Currently the Dogwood portfolio is being marketed as one lot. If that doesn't work, the 21 properties will be broken into eight or nine smaller groups, says Shears. "Already, we're getting a lot of interest in the smaller groups."

Williams, understandably, has mixed feelings about the liquidation, but he thinks it's time for Dogwood to move to the next level with general improvements: repainting, paving driveways, more extensive landscaping. "None of our apartments are in need of interior painting because we do that regularly," he says.

One of his former tenants, Frank Fountain, sees Williams as having moved to the next level, as well. "He was able to reinvent himself and move forward with the next level of integration," explains Fountain. "In the '50s, he integrated the schools. Then he integrated where people live."

Fountain is white and works in procurement at UVA. He used to rent a Dogwood apartment at 407 Ridge Street. "As a landlord, [Williams] was great," says Fountain. "It's such a much more purposeful vision than the average landlord has."

Fountain has since bought a house on 10 1/2 Street, where he lives with his wife and son. "It's a great value," he says. "It's a great neighborhood."

A lot of the changes in the 10th and Page neighborhood Fountain credits to Williams. "Before Mr. Williams bought [houses], they were not the best looking. The commitment he had in gentrifying, he was an incredibly stabilizing force."

For many, that g-word is anathema, signaling the loss of low-income cheap housing to more affluent, wine-sipping yuppies. But Eugene Williams doesn't see gentrification as a bad thing, because he believes everyone benefits when housing conditions are improved.

"I mostly worry about continued job discrimination," he says. "How can you buy a house if you can't get equal opportunity employment?" In Williams' opinion, the city has not done enough to integrate its ranks.

At 79, Williams is not about to stop pointing out what he sees as social wrongs. Yet he admits to some pleasures, too.

"It's most rewarding to me to have been born during the segregation period when blacks and whites were not educated together, didn't live together or eat together," says Williams.

"There's so much pleasure seeing people having better houses, children happy, families renting until they can move into their own homes," he continues. "There are so many satisfactions in being a landlord that the little negatives you experience don't remain with you."

And while Williams is always modest about his role in Dogwood Housing, others are less reticent about applauding his vision and determination.

"He's the real mayor of Charlottesville," says Mel's Cafe owner Mel Walker. "He's made a lot of things happen. He's had a tremendous impact on the city. A lot of leaders say they come to him for advice."

For over half a century, Eugene Williams has been a striking presence in a crisp suit and his signature bowtie, but as he plans to spend more time with his family, he admits he might even dress a little more casually. And he knows what he kind of legacy he wants.

"I would like people to be more vigilant at seeing where discrimination or segregation exists in education, employment, housing," he declares. "It's still present in every one of them. People should still keep working to eliminate these areas of injustices because of people's race, class, or philosophy."

That's what Eugene Williams would do.

Eugene Williams has mixed feelings about liquidating Dogwood Housing, the rental company he founded, but he proved that different races and economic levels can live together– and property values will still go up.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Hortense Cruz is disabled and depends on subsidized housing. She worries that once Dogwood Housing is sold, the new owner may not want to continue that tradition. "I don't have any other place to go," she says.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Satyendra Huja calls the city's $200,000 loan guarantee for Dogwood Housing "unprecedented."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Frank Fountain is a former Dogwood Housing tenant and now lives in a traditionally African American neighborhood– "the next level of integration," says Fountain.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Scheryl Williams Glanton is the second generation to work at Dogwood Housing, and she's proud of her father's efforts to build something that encouraged self-sufficiency. "That's a civil rights issue," she says. "Self-sufficiency allows more voice."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Eugene, Lorraine, Emma, and Albert Williams are general partners in Dogwood Housing and dedicated to the ideal of providing decent housing to the underserved. They also demonstrated that such a business model can be profitable.

PHOTO BY JIM CARPENTER

#