NEWS- Presidential campaign: Changing views of Tom and Sally

Whimsical, thought provoking, or just plain insulting? That's what some are asking about a campaign at UVA that aims to knock school founder Thomas Jefferson off his pedestal and bolster the recognition of his African-American slave and mistress, Sally Hemings.

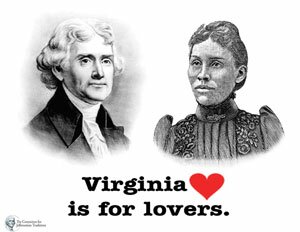

Dubbed "Tommy Heart Sally," the campaign that began in January is the brainchild of a new secret society, the Committee for Jeffersonian Traditions. On its website, tommyheartsally.com, various t-shirts feature images of Jefferson and Hemings accompanied by slogans, including the classic "Virginia is for Lovers." Also on the site, the group announces its commitment to "celebrating all of our beloved Jefferson," and cites the third president's "many passions."

Chief among them: Hemings, whose relationship with Jefferson was rumored for nearly 200 years before DNA tests in the late 1990s led many scholars to admit Jefferson had almost certainly fathered some or all of Hemings' six children.

To celebrate Hemings' life, the Committee announced plans to throw a birthday bash for Hemings on Friday, April 20, at Amigo's Mexican restaurant on the Corner. The event, which starts at 11pm, features margaritas for $2.50 and draft beer for $1.50– with an "event cup."

Tommy Heart Sally campaign spokesperson Keith Cox says he hopes the celebration will bring students and townspeople of both races together. He expects that holding it late at night and offering cheap booze will lure more students. But not everyone has been thrilled with the approach.

"It seemed flip, casual, sort of mocking," Cauline Yates, a descendent of Sally Hemings' sister, said when a reporter told her of the event. Yates, a Charlottesville event planner, said no one had called her for input about the campaign.

Dorothy Westerinen, a direct descendant of Jefferson and Hemings who now lives in Staten Island, New York, also hadn't heard of the campaign. She says she applauds the idea behind the Tommy Heart Sally campaign, but she worries about the method and the tone.

"I wouldn't want her to be demeaned," she says of Hemings, pointing out that while Jefferson was a public figure and therefore subject to "some flak," Hemings was not. "People know very little about her," Westerinen says, "so if they're being cheap with her image, I'd be more upset."

Cox says he and other Committee members tried unsuccessfully to reach Hemings descendents. He insists that neither the campaign nor the party is intended to be disrespectful. And, he points out, several faculty members have approved the campaign.

"I see it as whimsical," says Valerie Cooper, assistant professor of English, who is African American. Of Cox, who is white, she says, "He's very bright, and I'm impressed with his social consciousness." Cooper says her father grew up in Charlottesville and she recalls hearing "stories about Thomas Jefferon's liaisons with Sally because it was part of local popular culture."

Indeed, most of the information about Hemings and Jefferson has been perpetuated in the oral tradition. There are no images of Hemings in any historic record and very little written about the woman who many believe was the half-sister of Jefferson's wife, Martha. What scholars do know is that the rumors of the Hemings liaison dogged the third president so much that he argued for restrictions on the press. Mixed-race children roamed the grounds of Monticello, as they did many other southern plantations. Sally, after all, had only one-quarter African ancestry, as three of her four grandparents were white. Adding to speculation that the relationship was more than simply master/slave, after Jefferson's death, the Hemings family was the only one specifically freed in his will.

Sally Hemings lived out her years as a free woman in a house on West Main Street, now the site of the Hampton Inn. One of her sons, Madison, freed the year of Jefferson's death in 1826, later moved to Ohio where, 47 years later, he gave an extensive newspaper interview confirming the rumors about his parents.

Cooper says several of her students– mostly African American women– have approached her expressing concern about the current campus campaign and suggesting it may be demeaning.

"African American women are used to having their images and honor batted around," says Cooper, mentioning the recent flap over comments made by talk show host Don Imus. "They're very protective about this story." Citing Hemings' age at the time the relationship began– 14– Cooper says thinking and talking about what happened can be difficult since one possibility is it was rape.

English professor Eric Lott believes the campaign is an important start to meaningful discussion. The graphic design on the t-shirts and website are intriguing, he says. "It's an interesting puzzle," says Lott. "What does it mean that Jefferson hearted Sally? Are we focusing on love? Are we focusing on what he wrote and what he did in practice? We're talking about a white supremicist who had a relationship with a black woman and had at least one child with her."

But the fact that the campaign and its accompanying imagery may be offensive to some is not necessarily a bad thing, Lott says.

"Even to wonder whether this is trivializing is to enter the terrain of the puzzle," he says, "and this may be a useful thing."

Hoping he could prove the Committee's good intentions, Cox met with Yates on Friday, April 13. "I told her we'd cancel the event if it upset her," he says. "That was never our intent." But after a three-hour meeting, there was no cancellation. Instead, Yates joined the campaign, and the two decided to expand the birthday celebration by starting the event at 8pm with speeches by Yates and by a yet-to-be confirmed Monticello historian.

UVA spokesperson Carol Wood declined comment on the campaign, as did Thomas Jefferson Foundation president Dan Jordan. One bigwig who did pay attention: Daily Show host Jon Stewart, who requested a t-shirt and may reference it in his show on April 28 at the John Paul Jones Arena.

Cox says giving attention to Hemings helps accomplish the campaign's other long-term goal: humanizing Jefferson and destigmatizing his biracial relationship.

"We hope our images will become part of the UVA iconography," says Cox. "The way we imagine Jefferson will be more truthful."

A new twist on the Virginia state slogan

IMAGE COURTESY COMMITTEE FOR JEFFERSONIAN TRADITIONS

#