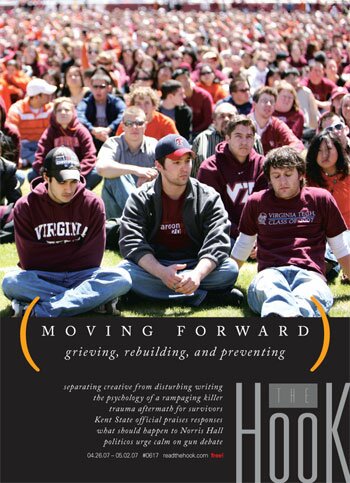

COVER Literary tragedy: Writing profs read between the lines

On April 16 in Blacksburg, a 23-year-old student who wrote plays and poetry authored a tragedy that has left the world dumbstruck. In taking violent fantasy to reality in one fantastic leap, the author carefully orchestrated his tragedy for maximum effect, mailing video, photos, and rants to NBC News before the climax of the story.

On April 16 in Blacksburg, a 23-year-old student who wrote plays and poetry authored a tragedy that has left the world dumbstruck. In taking violent fantasy to reality in one fantastic leap, the author carefully orchestrated his tragedy for maximum effect, mailing video, photos, and rants to NBC News before the climax of the story.

Seung-Hui Cho had no close friends, and counselors and police found no legal or psychological reason to intervene when his writings drew the worried attention of his teachers. So it was left to those Virginia Tech creative writing instructors to wonder if his words were merely provocative forms of expression– something teachers see and usually encourage– or were there signs that his violent fantasies were about to leap off the page?

As widely reported, Cho was an English major and a creative writing student who produced work and displayed behavior disturbing enough that two of his professors, Nikki Giovanni and Lucinda Roy, removed him from class and insisted he seek counseling.

Giovanni went so far as to threaten to resign if Cho wasn't removed from her class, and Roy– who had contacted the police about him– began tutoring him one-on-one because other students were so disturbed by his behavior. "He was one of the most disturbed students I have ever seen," she told Matt Lauer on the Today Show.

However, as Roy explained, the police could do nothing because there were no explicit threats in the the pre-shooting writings she turned over to them.

"All of us who teach creative writing face this judgment call from time to time, and it seems to me that Lucinda Roy did an exemplary job," says UVA creative writing professor Christopher Tilghman. "Problem was, she clearly was facing an extraordinary case."

Indeed, as University of New Mexico creative writing professor Dan Mueller points out, "When students display disturbing behavior, or write disturbing things, 99.9 percent of the time this kind of thing doesn't happen."

Cho was no literary genius, as evidenced by the plays posted online by a classmate, but he expressed his anger, his wish for revenge, and the way he felt persecuted.

"It's been known for a long time that psychologists and psychiatrists are not very good at predicting violence," says John Monahan, a nationally known expert on the issue of violence risk assessment. "They're better than chance, but not much better."

Monahan says the science has improved considerably in the last few years, giving mental health professionals new tools to make more accurate predictions.

"But still, our crystal balls are very murky," says Monahan. "We have a long way to go to really understand what makes anyone act violently, let alone on such a horrific scale."

Tilghman says he has twice feared for a student's own safety. While teaching at another school, he once contacted the dean and school counselors.

"I didn't think twice about doing it," he says. "Anyone who has dabbled in fiction understands the difference between fictional narrators, characters, and the author, and artistic license demands that we not equate them, especially when the material shocks or offends us.

"But it's relatively easy– I mean really easy– when reading fiction from young, inexperienced writers to spot cases where it's the writer speaking, where it's his or her demons controlling the text."

In 27 years of college teaching and advising, UVA poet Lisa Russ Spaar says she has suggested counseling to as many non-English majors as majors, and has even accompanied a few depressed students to Student Health.

"It's hard for us because of course we're poets and fiction writers, not therapists," says Spaar, "and creative writing is not therapy, nor are workshops encounter groups."

Mueller, who was enrolled in the UVA Creative Writing program, is known for stories that are often extremely violent. In fact, he recalls being bumped from an interview at a Charlottesville radio station during a book tour in late 1999, the year the Columbine shootings took place, because the station managers were concerned about his subject matter.

"For all the horror of some of his stories," says Tilghman, who has known Mueller for years, "Dan is about the sweetest, most principled person I've ever met, and anyone who spent three minutes with him would recognize it. Now that I think of it, the same could be said of Stephen King, a legendarily generous and kind individual."

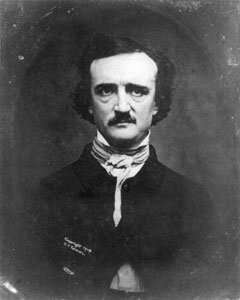

Indeed, literature is crowded with violent stories. Tragedy marked by violence is a narrative tradition as old as human history. Think of Greek or Shakespearean tragedies. Think Hitchcock, Scorsese, Tarantino, King, O'Connor, and Kafka. Or better yet, think of former UVA student Edgar Allen Poe, who wrestled with alcohol issues and penned a chilling story of fatal revenge in his tale, "The Cask of Amontillado."

"Everyone has psychological problems," says UVA poetry professor Debra Nystrom, "and turning to art and literature is a way to feel less alone."

However, in Cho's case, turning to literature wasn't enough. Instead of writing about his demons, he became one. And like Poe's protagonist, he blamed his victims for various perceived slights.

So in a world of cloudy crystal balls, can there be any clarity on the question of what makes one student willing to exorcise his demons in bloody real time?

"Interestingly, the alarm bells go off often not simply because of the actual plot or even the material," says Tilghman, "but because of attitudes and impulses in the text that seem to suggest a troublesome take on the violence. It's what comes through that even the writer isn't aware of. That's where the judgment call has to get made. Are you, as a teacher and reader, right about this, and is the trouble pursuing this writer bad enough to call the cops?"

Spaar: "We're poets and fiction writers, not therapists."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The original scary Virginia writer

FILE PHOTO

#