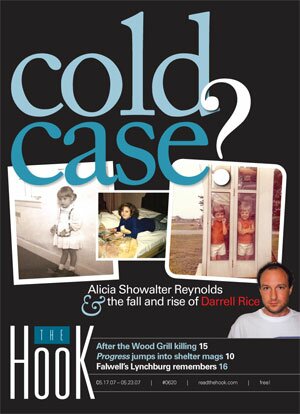

Cold Case? Alicia Showalter Reynolds & the fall and rise of Darrell Rice

This week's story is mostly about the terrors on Route 29, a series of illicit pull-overs that culminated in the 1996 disappearance and murder of Alicia Showalter Reynolds. Next week: the Shenandoah National Park murders.

The white wooden cross has broken free of the guardrail and lies on the shoulder as cars rush past; its red bow and artificial greenery, buffeted by blustery spring winds, have flipped over and come to rest in the gravel and dust.

As cars flew past that spot on a March day in 1996, some drivers noticed a young woman standing near her white Mercury Tracer on the shoulder and talking to a man whose pickup truck was parked nearby. The hood of the car was up, and the man and woman were studying the engine; some observers saw her getting into his truck. She was never seen alive again.

Since then, her name– Alicia Showalter Reynolds– has been etched into the minds of many Central Virginians because of what happened to her that day. But the man was never found. Or was he?

Some believe the man at the side of the road was Darrell David Rice– and federal prosecutors believe that less than three months after Alicia disappeared, he murdered two women in the Shenandoah National Park.

Rice, who has been held nearly 10 years for another crime in the Park, will be released from federal prison in two months, and his attorneys say it's unfair to link his name to other crimes. Indeed, 11 years after Alicia's disappearance, State Police have yet to charge anyone with her murder.

Even so, Darrell Rice continues to be a suspect in the three killings in 1996– which, for women in Central Virginia, was a very bad year.

As soon as Alicia's disappearance was announced, calls began flooding Virginia State Police headquarters in Culpeper from other women reporting that they too had been stopped along Route 29, usually in the Culpeper area, by a man in a pickup who would flash his lights and gesture. If the woman pulled over, he would park nearby and tell her that something was wrong with her car– usually, that sparks were coming from underneath. Then, saying it wouldn't be safe for her to drive, he would offer a ride.

The man quickly became known as the "Route 29 Stalker," and fear began to spread. Wireless phone companies in Central Virginia reported that interest in cell phones went up in response: For many women, Route 29 no longer seemed safe, and residents of the region worried about female family members and friends who drove alone, especially at night.

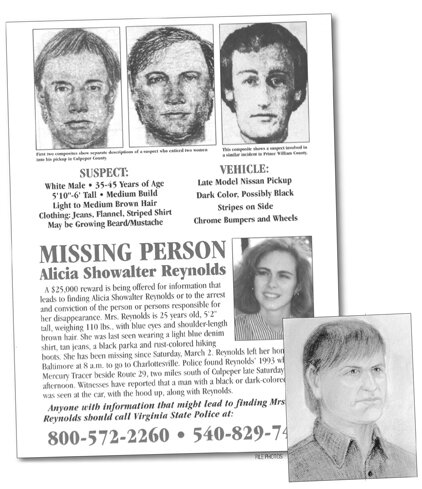

According to a press release issued by the State Police two months later, the abduction fit a pattern. The women described the suspect as white, age 35-45, 5'10" to 6' tall, 189-190 lbs, and clean-shaven with short, light-brown hair longer in the back than on the sides. He was also well-spoken, with a "clean, casual appearance."

All of the victims said the man was driving a pickup, but accounts of the size and color varied. "Suspect may have had access to more than one vehicle," the police briefing stated, "not to exclude a Ford Ranger/Mazda or a Nissan pickup truck. He may also have recently purchased, sold, or otherwise changed vehicles during the course of these contacts." Based on calls from drivers who claimed to have seen Alicia and the man on the shoulder of the road, State Police investigators felt confident that the truck had been dark-colored with a "splash" or streak in a lighter color, possibly teal.

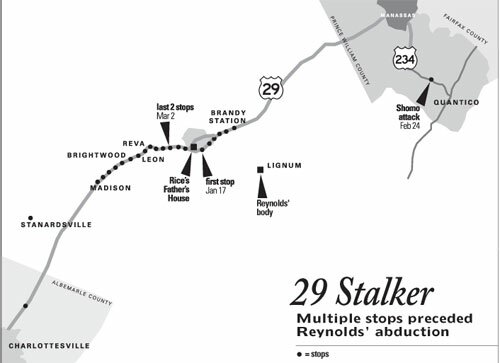

The incidents began on January 17, 1996 and ended on March 2, the day Alicia disappeared. There were 23 stops during those 46 days, including one for which the date is unknown [see map], with the great majority located along a 20-mile stretch in the vicinity of the Culpeper exits.

Most of the women rebuffed the man and drove away, but in addition to Alicia, three got in his truck. Two were dropped where they requested. The third, Carmelita Shomo, was attacked, but she survived– in fact, she did more than survive. Nine years later, she faced Darrell Rice across a courtroom and identified him as the man who had abducted, attacked, and left her beside the road, screaming for help.

It was raining and cold when Carmelita Shomo headed south on Route 234 the night of February 23, 1996. She was driving home to Quantico after her Friday-evening shift as a custodian at the Manassas Mall. Near a crossroads called Independence Hill, she noticed flashing lights in her rear-view mirror. This account of what followed is taken from her March 5, 1996 interview with FBI Special Agent John Zero.

Shomo pulled onto the shoulder, and the man parked behind her. As he approached, she thought he might be a friend of her husband and rolled down her window and asked, "Do I know you?" But he was a stranger, and he said he had seen sparks under her car, perhaps from "a loose bolt" or "the CV joints going bad." He said it wouldn't be safe for her to drive, because the brakes might give out. Then he offered to drive her home, and she accepted.

He suggested that she hang something from a window of her car to identify it as having broken down. (As was the case with all the women who were told something was wrong with their cars, Shomo later learned that her car was fine.) She hung a rag, locked up, and climbed into the truck.

The man drove her approximately three miles down 234– which, in 1996, was two lanes instead of four– through an area that was less populated than it is now. Three times, the man said that headlights from the cars behind were causing glare on his windshield, and pulled over until the vehicle had passed.

They talked as they headed south in the rain. The man asked her to show him where she lived; she asked his name, and he said it was Larry. He wanted to know how she'd get her car home, and she replied that her husband could tow it himself. Then he asked whether it was an automatic or stick shift, and when she said it was an automatic, he suggested that they go back; he would drive her car, and she could drive his truck to her residence. She said that wouldn't be necessary.

By this time she was getting uneasy and asked him to drop her off at an all-night gas station near the intersection of 234 and the Montclair subdivision. Instead, he pulled over for a fourth time and, again complaining about glare on the windshield– which she couldn't see– asked her to hand him a tissue from the pocket on the passenger-side door.

Then he attacked. Grabbing her neck, he shoved her head toward his lap. In his right hand, Shomo stated, he held a screwdriver pointing at her neck. He told her to "shut up and put your head down in my lap," but she fought back, elbowing him in the chest as they struggled. Somehow, the passenger door came open; Shomo thinks the man must have opened it, because by then he was yelling at her to "get out of the truck."

As she slid toward the door, they both grabbed for her purse, and she fell out of the truck– with the purse left behind and one foot tangled in the seatbelt as he pulled back onto the road. She was briefly dragged before she could wrestle her foot free, breaking her ankle in the process.

Shomo told investigators that cars had passed her on the side of the road as she screamed for help, but no one stopped. Finally, an off-duty ranger for nearby Prince William Forest Park and his wife, whose house faces Route 234, heard her and came out. The ranger used his police radio to call for help.

Raised in the Philippines, Shomo was not fluent in English, and the communication gap would prove critical. Officers and emergency-room personnel assumed that Shomo's husband had been her attacker, and Prince William County police didn't assign a detective to the case until the next day, when Shomo finally got someone to understand that she had been abducted, attacked, and robbed by a stranger.

The misunderstanding meant that during the hours that followed, no alert was issued for a vehicle matching the description Shomo provided– hours during which three more women were stopped. (None, however, got in the truck.)

Beginning two days later, on February 26, there were five more stops before March 2, when Alicia was abducted: one on Monday, two on Wednesday, one on either Monday or Wednesday, and one on Thursday. The frequency suggests that by Saturday, March 2, 1996, the man was determined to find a victim.

At about 10:15am, he attempted to stop a woman heading north on the other side of 29 from where he would soon stop Alicia. Shortly after that, heading south on 29, a man in a truck stopped Alicia. She was his final victim.

Three weeks later, Detective L.J. McDonnell of the Prince William County police wrote: "After reviewing the State Police reports, I have isolated 15 points that link [the Shomo] investigation with the reported incidents in Culpeper County." In addition to driving a truck and always choosing petite female victims (Shomo was about 5' and 100 pounds) who were driving alone, the suspect would flash his headlights and signal the driver to pull over, tell her something was wrong with her car and that it wasn't safe to drive, and offer her a ride. Women who accepted rides and survived also said the man told them "to leave a white item on the vehicle to signify that [it] was disabled," to step on a jacket on the passenger-side floor of his truck, asked them "to search for an item in the door pocket," and said his name was Larry.

The State Police had reached the same conclusion– that the Prince William attack was linked to the Route 29 incidents– and they ended their May 13 press release with this statement: "After a thorough review of all the victims' statements, police believe that all the incidents involved are the same person."

The statement they needed the most, of course, was the one they could never have.

Perched atop a hill, Harley and Sadie Showalter's spacious home in Harrisonburg is surrounded by well-tended garden beds and lush green grass sloping down to the street. The living room is dominated by two bold paintings of flowers the Showalters bought on a trip to Quebec, but most compelling is a portrait of Alicia that hangs in one corner: It would be hard not to sense the fierce emotions that surround it.

Harley sold his insurance agency in downtown Harrisonburg last year, and he now offers financial services. Sadie, who taught elementary school before their children were born, later helped set up the first computer lab at the junior high. They met as students at Eastern Mennonite College (now University). Although the branch of the Mennonite Church they belong to is pacifist– like almost all branches of the church– it largely resembles other mainstream Protestant denominations.

The Showalters are gracious to reporters, which isn't always easy. In the media crush that followed Alicia's disappearance, Harley says, some were "not considerate." And the Showalters remain bitter that when the horrific outcome was finally revealed, the news was leaked to the media before investigators contacted them.

As Alicia's image smiles down from the corner of the room, her parents tell the story.

"It was a gorgeous day," Sadie Showalter says– a gorgeous day to drive east from Harrisonburg across the Blue Ridge and south to Charlottesville, where mother would meet daughter at Fashion Square Mall and hear about life as a fourth-year graduate student in pharmacology at Johns Hopkins.

They'd planned to meet at 11am, but Alicia, driving down from Baltimore, was always early. So her mother left home in time to arrive at 10:30 at the women's petite section at Leggett– now Belk– and began looking through the formal dresses. Their mission was to choose a dress for Sadie to wear to the May wedding of Alicia's brother, Patrick.

When 11am passed without Alicia, Sadie called her son-in-law, Alicia's husband, Mark. He planned to study all weekend; with Alicia's support, he had decided to leave his career as a CPA and enter dental school at the University of Maryland. This weekend, he was working on science prerequisites. Mark told his mother-in-law to give Alicia a few more minutes, then call again if she hadn't arrived. When Sadie called him again at 11:30, he had gone online via a dial-up connection and couldn't be reached.

For the next two and a half hours, Sadie sat on a bench inside the Leggett entrance that looks out on Route 29 and tried to will Alicia's car to turn into the parking lot. Periodically, she called Harley on her cell phone (which was so new to her that when Alicia had asked for the number the night before, Sadie had had to go in search of it and call her back).

After two hours of trying "desperately" to get hold of Mark, Harley finally succeeded at 2pm, and Mark immediately began calling the State Police. This was no easy task, since in 1996 there was no communication system linking the various divisions. This meant that he had to call each of the Maryland and Virginia State Police divisions between Baltimore and Charlottesville.

At that point, Sadie abandoned her vigil, left the mall, and headed up Route 29 to drive home. Just as she was about to turn left onto Route 33, she had the impulse to keep driving north on 29. But she pushed it aside and drove west instead, home to Harrisonburg to wait.

"The first two weeks were the worst," Sadie says. Every morning, someone from the State Police would come to make a report– but there was rarely anything to say.

Evidence pointing to foul play quickly emerged. At 1:15 that first afternoon, a woman on Clay Street in Culpeper, which is about five miles from where Alicia had been abducted, found her Citibank MasterCard and called the number on the back to report it. And at 6pm, Alicia's car was found three miles south of Culpeper.

The family gathered quickly. Patrick– who was not only Alicia's brother but also her twin– came from Nashville, where he was in his last year of medical school at Vanderbilt, and their younger sister, Barbara, arrived from Indiana, where she was a senior at Goshen College. Mark was there, along with Showalters from around the region and relatives on Sadie's side of the family from Ohio. The phone rang nonstop, mail flooded in, reporters hovered nearby– but nothing changed.

Also recovered the afternoon of March 2– but not turned in to the State Police until March 8– was a black parka, later identified as the one Alicia had been wearing. It was found in Madison County on Route 626, less than a mile east of Route 29, at about 2:30pm. On March 9, the last items– several more credit cards– were found in Culpeper.

The time came when Mark, Patrick, and Barbara had to return to school, and at some point Sadie told herself that life had to go on. But those departures didn't render the day-in/day-out silence any less agonizing.

It ended on Tuesday, May 7, when a man walking along a country road outside Lignum, in a rural part of Culpeper County, saw buzzards circling over a field that was being cleared of trees. When he went to investigate, he glimpsed a body under several fallen logs in a gully that was invisible from the road.

"Thank God for buzzards," Harley would later tell reporters, explaining that the birds had put an end to nine weeks of waiting: A long-indrawn breath could at last be released. And the next part, where Alicia came home to her family, could finally begin.

"It was pouring rain that night," Special Agent Stan Gregg says, which made an already difficult crime scene even harder to process. A State Police investigator in the Violent Crimes Unit, Gregg worked in the muddy field throughout the night of May 7 and for two or three days in his other role, that of crime scene technician. Nearly fours later, he officially joined the investigation as a detective.

The body was in a state consistent with two months' decomposition, which meant that Alicia had almost certainly died quickly. Between the heavy rain and the fact that two months had elapsed since her murder, the scene didn't yield many clues– and what clues it did give up, such as the cause of death, are closely guarded by Gregg, who is now the only investigator officially pursuing the case.

Roughly 10,000 tips poured into the State Police hotline; Gregg says he can tell when America's Most Wanted reruns its 1996 segment on Alicia, as he always gets another wave of calls.

Only later would one tip stand out in a way it hadn't at the time. The call came from one of Darrell Rice's coworkers back in Maryland, who called the hotline because Rice had been "acting strange." Gregg says that like all such calls, the tip was "given to someone to complete, and it was completed." "Completed," he explains, could mean many things, including that the person didn't resemble the composite sketch. In any case, all Gregg says he knows now is that the tip was considered completed and filed away.

Alicia's memorial service was held on Mother's Day. Twelve hundred people came to Park View Mennonite Church; they filled the sanctuary of the church she'd grown up in and overflowed into rooms fitted with monitors, rooms she had moved through hundreds of times for Sunday School and youth group and parties from the time she and Patrick had played in the nursery to New Year's Eve of 1994, when she'd come back to be married.

The Showalters buried their daughter in a small cemetery next to Trissels Mennonite Church in the rolling countryside outside Harrisonburg. In the weeks that followed, Patrick graduated from medical school, Barbara graduated from college, and Patrick was married.

Since the murder, her sister Barbara has also married, as has the young widower Mark, now a dentist in Greensboro, North Carolina.

All three– Patrick, Barbara, and Mark– have children. Alicia had told family she planned to weave her life as a researcher into her life as a wife and mother. She had been researching bilharzia, an often debilitating disease endemic in developing countries, and Johns Hopkins was so taken with its Alicia's enthusiasm that it created an annual award in her name.

Instead, she looks out from her portrait in the corner, always young, always smiling– always gone.

Throughout Central Virginia, the discovery of Alicia's body and the knowledge that her killer was still free elevated fears of the Route 29 Stalker to new heights. Ironically, he has not struck again. Yet only three weeks later, the region was once more rocked by violence.

On May 18, 1996, the Saturday after Alicia was buried, two young women– Julie Williams and Lollie Winans– began driving south from Vermont to Virginia, where they planned to hike and camp in the Shenandoah National Park. Julie had to be home by May 29, but until then they would explore the mountains with Lollie's dog, pitch their tent wherever they liked, and explore the serenity and beauty of the mountains.

They never left the Park. Instead, two rangers found their bodies just past twilight on Saturday, June 1, at a secluded campsite near Skyland Lodge. Once again, Stan Gregg would be called in as a crime scene technician, this time alongside agents from the Park Service and FBI. And once again, like the field outside Lignum, there would be frustratingly little evidence.

Fifteen thousand leads would eventually be followed– to ends as frustrating as what the State Police found in Alicia's case. But then, in July of the next year, Yvonne Malbasha, a bicyclist in the Park, was stalked and attacked by a man driving a pickup. This time the investigation was over in a matter of minutes, because Malbasha was found by a ranger soon after her frustrated attacker sped off. The ranger radioed the man's description, and the attacker, in a blue Chevy S10 pickup, was stopped at the Swift Run Gap exit at Route 33. Malbasha identified him immediately, and he was arrested. It was Darrell David Rice.

Rice had been living in Columbia, Maryland, and, court documents indicate, had been fired from his job making software manuals for MCI Systemhouse (now part of EDS) a week and a half before the incident. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison. Although he resembled some of the police sketches of the Route 29 Stalker, he was only 28 years old during the stalkings, a little younger than the police's stated age range of 35 to 45. And there was no evidence he was involved– even though, in the hours after he was taken into custody for the attack on Malbasha, he allegedly made statements to a federal marshal that Prince William County might have deemed worth investigating.

In an interview with Stan Gregg on March 4, 2003, U.S. Marshal Larry Carter (now deceased) claimed that Rice admitted

to a "rage against women" that sometimes erupted when he was on the highway and that he liked to "run women off the road" on Route 29. When Carter asked what he did after that, Rice said he would "just keep going." To a question about Alicia Showalter Reynolds, however, he told Carter he "didn't know who that was."

In 2005, in a Prince William County courtroom, Carmelita Shomo took the witness stand and swore that Rice was the man who had abducted, attacked, and robbed her. Rice's defense team labeled her identification of Rice as unreliable, since six years had elapsed before she was shown the photo lineup. They also pointed to inconsistencies they claimed stretched back to her earliest statements to police.

Sam Newsome, who is a Master Detective with the Prince William County Police, administered the 2002 photo lineup and claims Shomo has never wavered in her identification. "I have no doubt that Darrell Rice abducted Carmelita Shomo," he says. "Had I had any doubt, we never would have charged him."

Investigators also testified that according to Rice's employment records, he had been off work on all but one day during the period when 18 of the women were stopped. His defense team, however, disputes this. Also, in 1996, his father, Leon Emile Rice, was living in a rented house in Culpeper. Located at 600 Jaynes Lane, the dwelling is convenient to Route 29, which investigators believe Rice could have used as a base of operations.

The trial, which hinged almost entirely on Shomo's testimony, ended when Rice took a so-called Alford plea, in which he claimed innocence while admitting there was enough evidence to convict him. In a statement he made to the judge before being sentenced, Rice said, "I am not guilty of the crimes I was indicted for. This is all for strategic reasons. It is in my best interests to return to my family"– referring, presumably, to the fact that as part of his plea agreement, no time was added to the sentence he was already serving in federal prison.

The abduction of Carmelita Shomo marked the beginning of a series of crimes against women in Central Virginia, and the attack on Yvonne Malbasha marked the end. In between, three women lay dead. Alicia's murder has officially been linked to the other incidents along Route 29, including the attack on Shomo, and investigators from the Park Service and FBI believe that the Rice is guilty not only of the 1997 attack on Yvonne Malbasha, but of the 1996 murders of Julie Williams and Lollie Winans as well.

In April 2002, at a highly publicized press conference at Justice Department headquarters, then Attorney General John Ashcroft announced that Rice was being indicted for the double murder, but the indictment was withdrawn in 2004. Some– but not all– investigators believe the crimes along Route 29 and the crimes in the Park are similar enough to throw suspicion on Rice.

Rice has staunch defenders. In a letter to The Hook, Deirdre Enright, a member of Rice's defense team, stated, "We are confident that Darrell Rice is innocent of the Shenandoah National Park murders, the 'Route 29' crimes, and the murder of Alicia Showalter Reynolds. We are certain we could refute any serious assertion the government might make to the contrary." Indeed, as they are quick to point out, the indictment for the murders in the Park was withdrawn when DNA evidence threw the case into doubt.

Rice, now 39, will be released from prison on July 17, after serving 10 of 11 years of his sentence. He'll be reunited with his truck, which for now is being stored at Enright's house on Saint Anne's Road in the Meadowbrook Heights neighborhood. He plans to move to Baltimore, where his mother lives, and will be required by the terms of his parole to seek work. But just as he won't be able to erase where he's been for the past 10 years, it's unlikely he'll escape the cloud of suspicion that continues to swirl around him.

The Alicia Showalter Reynolds murder case is still an open investigation, and you can help if you know something. Call the State Police at 800-572-2260 or 888-300-0156.

Barbara Nordin is a Charlottesville-based freelance writer. Perhaps best known for writing the "Fearless Consumer" column during the Hook's first five years, she has covered Central Virginia mysteries since her award-winning 1997 report on the case of missing UVA student Patrick Collins.

Darrell Rice

FILE MUGSHOT

An early poster issued during the two months when Reynolds was missing. Inset: a later police sketch.

FILE PHOTO

Darrell Rice's truck is parked in a driveway on Charlottesville's St. Anne's Road

FILE PHOTO

A roadside memorial at the scene of the abduction three miles south of Culpeper. Insets (not seen here on web): Alicia Showalter getting married to Mark Reynolds fourteen months before the murder; in church Sunday school; hanging out her senior year at Goshen College; and sharing a phone booth with her twin brother, Patrick (she's the one on the right).

BARBARA NORDIN; FAMILY PHOTOS

The field in rural Lignum, where the body was found in 1996 is once again a tree farm.

PHOTO BY BARBARA NORDIN

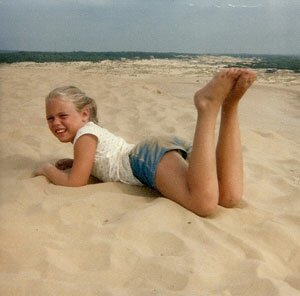

Alicia at age eight during the annual family trip to Nags Head.

FAMILY PHOTO

SIDEBAR- 29 stalker: Multiple stops preceded Reynolds' abduction

It was near Mountain Run Road at 11:30am on January 17, 1996 that smooth-talking "Larry," the Route 29 stalker, first appeared on the Culpeper Bypass. He didn't pull over a woman again until 6am on February 12. He waited two more days before resuming his ruse twice on Valentine's Day.

And then things began to accelerate. Between February 16 and 21, he stopped four more women – then two on the 22nd, one on the 23rd, and three on February 24, in one case just an hour and a half after Carmelita Shomo was robbed and dragged near Independent Hill, about 40 miles away.

Darrell Rice later took an Alford Plea in the Shomo case. That means he acknowledged that prosecutors had enough evidence to convict him, but he didn't admit guilt or serve any additional time on top of the sentence he was already serving for the attack on Yvonne Malbasha (that occurred a year later).

There were five more Route 29 stops between February 26 and 29.

On March 2, the State Police received two reports of women being stopped. One of them was Alicia Showalter Reynolds. And then, police say, the series of pullovers ended.

|

1. date unknown, 4pm 2. Jan. 17, 11:30am 3. Feb. 12, 6am 4. Feb. 14, 11:50am 5. Feb. 14, 6-6:30pm 6. Feb. 16, 5-5:30am 7. Betw. Feb. 17 and 21, 6:40am 8. Feb. 21, 3:15pm 9. Feb. 21, 8:30pm 10. Feb. 22, 7-7:15am 11. Feb. 22, 7:30-7:45am 12. Feb. 23, 7:12-7:15am |

13. Feb. 24, 12:30am (Carmelita Shomo) 14. Feb. 24, 2-2:15am 15. Feb. 24, 4:30am 16. Feb. 24, 7:20am 17. Feb. 26 or 28, 6:45am 18. Feb. 26, 2pm 19. Feb. 28, 6:45am 20. Feb. 28, 12:30-12:45pm 21. Feb. 29, 6:15pm 22. March 2, 10:30am 23. March 2, 10-10:30am (Alicia Showalter Reynolds) |

#