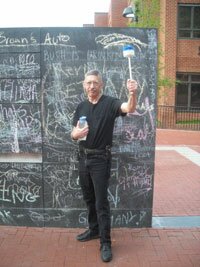

ONARCHITECTURE- Wall scrawl: Cox lays down his toilet brush

In April, Charlottesville resident Kevin Cox began erasing comments over the inscriptions on the Free Speech Wall, but now he's called it quits.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

After making Constitutional history by being the first person to defend the First Amendment with a toilet brush, Charlottesville resident Kevin Cox is calling it quits.

"I'm not touching it again," says Cox of the Downtown Mall's Free Speech Wall. "I'm just going to walk around it and not look at it."

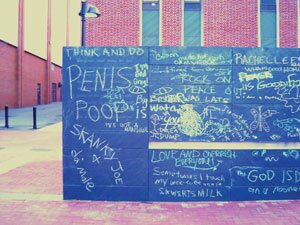

Cox has been a long-time critic of the wall, designed by local architects Peter O'Shea and Robert Winstead, likening it to a public bathroom stall and calling it an embarrassing eyesore right in front of City Hall. While supporters of the wall say that thoughtful comments greatly outnumber offensive ones, Cox argues that comments like "Kill the ni**ers," "I f***ed your momma," and "Kill the cops"– which he has documented– have a more disturbing impact.

"Supporters of the wall seem to think that their acceptance of all the crap on here reflects a true embodiment of the principles of free speech," Cox told the Hook. "But what I feel most is sadness. I'm sad that the noble ideal of free expression in American life has been debased by a monument that serves as a platform for profanity, hate speech, vulgarity, and pornography."

To prove his point, Cox went so far as to ask Charlottesville Mayor David Brown if he could begin bringing photos of offensive wall comments to City Council meetings to read them aloud during the public comment period.

"Would I be allowed to repeat these expressions? Or would you censor my repetition of the expressions on the Free Speech Monument?" Cox wrote Brown in an email. "Some of you support the chalkboard, so I think you should be willing to hear what's written on it."

Brown replied that he would not allow Cox to read the comments. "There's a level of decorum appropriate to a public meeting that I think we should maintain," Brown wrote to Cox in a March 20 email. "People would find some expressions offensive, no doubt; but at least on the wall people can avoid them, or even erase them."

Like so many wall supporters who admit they are troubled by the offensive comments ("I was concerned about the chalkboard when it opened that it would be dominated by profanity, personal insults, and slurs," wrote Brown), the mayor claimed that the majority of the comments are not offensive.

"Overall, I think the chalkboard is a success," he wrote, "and helps us to think about and discuss our freedoms."

Finally fed up with the offensive comments, and in particular with the way the inscriptions of the First Amendment and a quote by late Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall were being obscured, Cox began a crusade in early April, on his walk to work every morning, to clean those sections of the wall with a toilet brush and a bottle of water.

As he told the Hook, "You can't get an education if you can't read the text... I love the idea of an interactive monument that teaches free speech, but this just isn't doing it."

However, not everyone agreed. Constitutional attorney John Whitehead even went so far as to say that the First Amendment is there "so people can obscure it."

A self-described "free speech purist" and one of the few unapologetic supporters of the wall, Whitehead said he admired Cox's activism but summarily dismissed his position. "Sure, it might be a problem if you can't see the text," he said, "but people can write over it if they want. I have more of a problem with the wall's administrators wanting to change it."

Indeed, Josh Wheeler, associate director of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression, the group that built and oversees the wall, conceded that because the words of the First Amendment were obscured, he would present Cox's complaint to the citizens committee in charge of the wall at their next meeting.

On Monday, May 7, Wheeler finally met with the committee and reports that the group was unanimous "that we should not try to prevent people from writing over the inscriptions." While he noted that two members expressed regret that the inscriptions are so often obscured, he says even they opposed any physical change to the wall, mostly for aesthetic reasons. Wheeler adds that a majority of committee members shared Whitehead's view that preventing people from writing over the inscriptions was contrary to the philosophical principles of the First Amendment.

That appears to have been the final straw for Cox.

"I stopped because I think my vocal opposition may be counterproductive," he says. "I think it's obvious that the engravings should be protected, and I wonder if the committee's decision just reflects a certain stubborn refusal to publicly acknowledge an error."

Cox believes that pointing out public foible, something he's never shied from, often reinforces a commitment to stick with the program. "I want the engravings protected, and I think if I'm silent that has a better chance of happening," he says.

Cox, who suggested protecting the inscriptions in some way so they could not be written over, says he has been harassed and vilified by people for wanting to keep the inscriptions visible. He says it's not a monument and not a worthwhile forum.

"The reality," says Cox, "is that the chalkboard is a silly graffiti board."

Likening the Free Speech Wall to a public bathroom stall, Cox has been documenting the offensive comments that have appeared on it.PHOTO COURTESY KEVIN COX

#

1 comment

I liked the wall idea, and I tried it. The trouble was, the slate that was used is so uneven and grained that I couldn't comfortably write on it. It makes the writing look sloppy too. I was so very frustrated at this I gave up. The poor attention to detail here just ruined this potentially fun idea for me. It sucks.