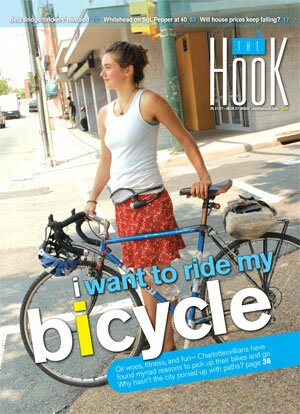

COVER- I want to ride my bicycle

In the six minutes just before 9am, 40 cars whiz past the corner of Key West Drive and Stony Point Road, northeast of Pantops.

In the six minutes just before 9am, 40 cars whiz past the corner of Key West Drive and Stony Point Road, northeast of Pantops.

Thirty six of them are inhabited by one person: the driver.

UVA physiologist John Hackett, however, smiles behind his sunglasses, swings his leg over his 18-speed Readline bicycle, and yells above the roar of the motorized blurs.

"I have a simple philosophy," the 65-year-old shouts as he starts the uphill. "I'm just planning for the next 20 years, like I do every year, by staying healthy today."

Hackett and UVA biologist Robert Kretsinger– who bikes the same general route before dawn– are likely the only two regular cyclists who brave 6,000-pound vehicles and six-ounce cell phones to maintain their health, spare the city some congestion, and save the nation's oil supply and the planet's atmosphere by commuting by bike over the twists and turns of two-lane– and no bike lane– Stony Point Road.

The vast majority of Charlottesville's other county-to-city commuters– 78 percent, according to the 2000 census– come alone in a car, spewing exhaust, carbon dioxide, and American foreign policy issues in their wake.

"As long as we sustain oil's influence with our habits, we're going to have problems," says Department of Defense contractor Daniel Ellsworth. "Oil is the root of so many of our national security issues."

Ellsworth plans his 11-mile, one-way bike commute down US 29 from Ruckersville, because-– having served in Iraq-– the 32-year-old knows first-hand the effect of America's daily reliance on 12 million barrels of imported oil.

"Working in national security, I can see that our current infrastructure and our way of doing things are appalling," Ellsworth says. "We're financing our own destruction, basically. We're just living for today and not thinking about tomorrow."

The numbers are indeed frightening. According to Uncle Sam, over half of America's daily burn of 19 million barrels of oil is in the form of gasoline or diesel while 87 percent of America's 411 billion annual trips are in private vehicles.

About 60 billion of those trips are commutes, usually during the so-called rush hours which, thanks to congestion, cause greater waste of fuel. In the words of the Texas Transportation Institute, in 2003, congestion caused "3.7 billion hours of travel delay, and 2.3 billion gallons of wasted fuel for a total cost of more than $63 billion."

Today, the transportation sector, which produces less than 11 percent of gross domestic product, emits America's largest single amount of C02 into the atmosphere, five percent higher than industrial and 15 percent higher than commercial emissions. Therefore, unless the United States wants to gut the economy, the American battleground for global warming and fears of dwindling oil reserves must be transportation.

But, with few exceptions such as our local bicyclists, most Americans– Republican or Democrat, Libertarian or Socialist, liberal or conservative, Christian or Muslim– drive whenever possible. Only two percent of Charlottesvillians commute on a bike, and the number of Albemarle bicycle commuters is so low that statistically they fail to register at all.

U.S. gasoline consumption, meanwhile, grew 2.8 percent in March. In 2005, we spent $256 billion overseas to import oil.

***

Although Ellsworth is a relative newcomer to bicycle commuting, Hackett and Kretsinger began pedaling to work decades ago, long before anyone connected America's emissions of 1,959 million metric tons of CO2 to our 2.9 trillion annual miles in a car.

They bicycle daily for health reasons and for the love of nature.

"It's the issue of causation and correlation," says Kretsinger, who just started his seventh decade but looks a generation younger. "Do you bike because you're in pretty good shape, or are you in pretty good shape because you bike? I don't know, but I'm sure that biking every day doesn't hurt."

Like Hackett, Kretsinger bought property in the Key West subdivision 30 plus years ago primarily for the healthy seven-mile, 30-minute bicycle ride to UVA.

Still, to counter the effect of his "too-great-a-cook" wife, Hackett often cuts away from Stony Point Road at Darden Towe Park to wander along the Rivanna River Greenway toward downtown, or to loop south on his "Great House Tour" near Monticello and Ashlawn to stretch those seven miles to as much as two hours.

"This place is a beautiful place to ride a bike," he says. "I would argue that the Blue Ridge Mountains are certainly the most beautiful place in Albemarle County, probably in Virginia, maybe in the US. And, for that matter, I might argue the whole bloody world."

For similar reasons, Mary Rowe, who moved to the area this year, is frustrated that there are no protected bike lanes or trails along her commute from Rio Road to downtown.

"Biking should be a wonderful way to see the city," says Rowe. "There are lots of back lanes and trails you don't see from a car."

This 48-year-old now works downtown at the of the non-profit human habit-protecting Blue Moon Fund, but she formerly ran a consulting business from her bicycle in Canada. "I could drift past wonderful residential communities or old manufacturing plants and understand how they smell and how they look and how they functioned."

Here, however, Rowe finds area automobile traffic too daunting to discover the city's built environment. With so few bike lanes and almost no trails, the rush of SUVs on local roads pushed her to make her commute in a car, edging up our area's congestion count.

"There are probably only half a dozen access routes into the inner city, but they have almost no sidewalks, and no buffers between cars and other travelers," says Rowe. "There's all this natural beauty, and I just can't get out there and do it."

Last June, the city hired Chris Gensic as the Park & Trail Planner, a new position created to push the City's ambitious Bicycle & Pedestrian Master Plan. Charlottesville recently set aside $100,000 toward a multi-use greenway around town. But the efficacy of one bike/pedestrian coordinator with a $1.3 million total budget for greenways, bike lanes, and sidewalks in a city of 40,745 driving citizens and a $6.4 million road maintenance budget may be limited.

Even Dan Mahon, who has been Albemarle County's greenway coordinator for years, throws up his hands when a single land owner withholds permission for a greenway to cross her land. It's not worth his fight when so few voters imagine any type of daily transportation other than their personal cars, and dedicated cyclists like Ellsworth or Kretsinger already chance the traffic without fanfare.

None of the bicyclists interviewed for this article, for example, are members of The Alliance for Community Choice in Transportation, the Charlottesville Area Bicyclists Association, BikeWalk Virginia, or other groups trying to "think globally and act locally" about how automobile transportation affects national and international issues.

Without, therefore, the political muscle of say, the AAA, could muscle-powered transportation be getting short shrift in the political world? Government money for roads and bridges carries a lot of zeroes.

Economic estimates of city, county, state, and federal dollars subsidizing drivers range to $295 billion annually– excluding the costs of foreign policy excursions to countries with oil like Iraq, or the cost of carrier fleets in the Persian Gulf.

Few cyclists, meanwhile, seek the benefits available to alternative commuters. Only seven area bicyclists are signed up for the RideShare's "guaranteed ride home," which sends taxis to alternative commuters facing virtually any type of emergency, and– until the recent adoption of free fare for bicyclists– JAUNT has no remembrance of any biker using the bike racks on the front of their six commuting buses.

Patricia Paisley, a 20-year-old waitress and student at Piedmont Community College– who each day travels on her bicycle six miles roundtrip from Grady Road to downtown's Monsoon restaurant, and 18 miles on the days she's in class– may be the perfect example.

In addition to the societal benefits her bike commuting provides, she focuses on personal benefits: "As soon as I started learning anything about the effect of cars, I started doing what I could to stop making things worse," she says. "If you ride, you're getting stronger everyday. Bicycling is my tool for developing myself."

Hackett, Kretsinger, Rowe, and Ellsworth heartily agree, as do the 4.9 million Americans who travel to work or school on two wheels.

"It's kind of sad when you live in a situation with disincentives to having kids bike three or four miles to school," Kretsinger, 70, sighs from 20 feet up a ladder where he's trimming pine trees. "How can you expect kids to be halfway fit if they're driven everywhere?"

"That's the culture today, though," he says. "It's considered almost a sign of impoverishment if anyone walks or bikes."

#

Randy Salzman is a former communications professor and now a Charlottesville-based freelance writer. His last cover story in the Hook was a late February piece on a proposal to create a Charlottesville street car system.

Robert Kretsinger, with a pair of red lights mounted on the back of his helmet, is a man who bike commutes at 5am to avoid the traffic.

If you ride, you're getting stronger everyday," says Patricia Paisley. "Bicycling is my tool for developing myself."

"I'm surprised that there's not a more powerful surge of demand to make it possible," says Mary Rowe, who won't bike-commute on shared roadways.

Nora Byrd, a UVA employee, puts her mountain bike on a JAUNT bus from Fluvanna driven by Jeannie Haynes. Byrd took advantage of May's free JAUNT promotion for bike commuters, the first bicyclist to use JAUNT's multi-modal approach this year.

PHOTO BY JAUNT

The med school recently rescinded John Hackett's shower privileges next door to his office, but he still bikes to work there.

#