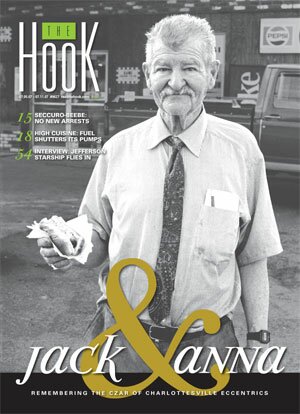

Jack & Anna: Remembering the czar of Charlottesville eccentrics

"I've been waiting since the day Jack Manahan died," began the letter published May 10, 1990 in the Charlottesville Observer, "to see either an article or a letter. Perhaps the New York Times had a piece. He certainly deserved it. He was, after all, royalty. Not because he was married to Anastasia, but because he was the king of us Charlottesville eccentrics.

"I've been waiting since the day Jack Manahan died," began the letter published May 10, 1990 in the Charlottesville Observer, "to see either an article or a letter. Perhaps the New York Times had a piece. He certainly deserved it. He was, after all, royalty. Not because he was married to Anastasia, but because he was the king of us Charlottesville eccentrics.

"He was our monarch not because he carried a dog food bag for a briefcase, not because he lived in houses overflowing with books, antiques, dogs, and cats and not because, given the slightest opportunity, he could tell almost anyone the name of their uncle twice removed.

"No, he was king because he left us all more alive with his effervescent good nature, his odd acts of charity, his wondrously weird speeches, and so much more. He woke us up from the common-placeness that is the plague of our age.

"I'd give a lot to hear him come into my bookshop and ask one more time, 'Sandy, have you Evan Meechum's book on the territorial rights of the Algonquins and their sisters in western Pennsylvania?'

"All of us need more people around us like Jack Manahan. I won't forget him. He woke me up."–Sandy McAdams, Charlottesville

John Eacott Manahan was probably Charlottesville's best-loved eccentric. Aside from his marriage to Anna "Anastasia" Anderson, he was truly a larger-than-life person. But the life story of the man many Charlottesville residents knew only as an amusing "character" is interesting and impressive.

A member of Phi Beta Kappa, he held high posts in several prestigious organizations such as the presidency of the Huguenot Society of Manakin. He received his bachelor's, master's (government), and doctoral (history) degrees from UVA. His father was a longtime dean of UVA's School of Education.

Jack's law studies at Harvard were interrupted by war. He attended Officer Candidate School at Columbia and Notre Dame, where, out of 969 midshipmen, he graduated ninth. He was number one in ordnance, number three in navigation, thirteenth in seamanship– but way down in engineering.

Following a two-year tour in the Navy during WWII, Jack began his teaching career in 1946 at Radford College. He also later taught history and political science at Massanutten Military Academy, the University of Maryland, and the College of Charleston in South Carolina. He worked and taught for UVA's Extension Division (now Continuing Education) from 1948 to 1955.

Almost every longtime Charlottesville resident over 50 knew or has heard stories about Jack. An employee at The Daily Progress says Jack often ordered food from Ken Johnson's Cafeteria (located near the site of what is now Ruby Tuesday's along Emmet Street), and when he went in to get the take-out trays, he'd stuff his pockets with condiments. Then he and Anastasia would sit in the car in the parking lot and eat their dinner, of which potatoes were always a part.

Anastasia believed the KGB wanted to kill her, and among other weird aversions, she would not eat from anything metal. Which explains why their battered old station wagon was always full of empty Styrofoam trays. Sandy McAdams says that once on a visit to his bookstore, Jack raised the back door of the vehicle, a 1968 Ford Futura, to reveal a box of puppies among the jumble of styrofoam. About a decade ago, McAdams pointed to a dog at his feet and told the story.

"That's where I got my dog," he said. "Anastasia was there, and Jack said, 'How can you go wrong with the offspring of a duchess?'"

Another Charlottesville man tells a story about being in Alderman Library doing research on his thesis in the 1980s, late in Jack's life when things were starting to slip. As he ambled by, other students stared at Jack with his untied shoes and disheveled clothes as they would a street person. But the thesis-writer squelched the snickers by announcing, "You just saw the son-in-law of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia."

After her famous 1920 rescue from a suicide attempt in a Berlin Canal, Anna Anderson spent decades living with European well-wishers and trying to prove that she was Anastasia Romanov, the youngest child of Nicholas and Alexandra, the one miraculous survivor of the royal family's execution by the Bolsheviks.

Her suit against members of Romanov family to prove her claims dragged through the German courts until 1970, when the German supreme court declared that her allegations could be "neither established nor refuted."

Two years earlier, she had shown up in Charlottesville shortly before her six-month American visa was to expire. Jack and Anna were married at the Albemarle County Courthouse on December 23, 1968 in a civil ceremony performed by Charlottesville police sergeant Raymond Pace.

Soon the longtime bachelor's living quarters, a small Italianate house on University Circle, began to deteriorate. Many stories and articles in local media detail the numbers of animals and shocking conditions inside and outside the house. In The File on the Czar, Anthony Summers and Tom Mangold write about a 1974 visit:

"The street is the epitome of American suburban affluence, but one house stands out. The garden is wild and untended, high grass spreads across the path, and creeper bars the way to the front door, in a way that suggests visitors are few and rarely welcome."

They authors find Dr. John Manahan. "He is in his fifties, crew cut, and paunch– a conventional American male who has let the conventions slip a little. The suit is baggy," they write, "the tie egg-stained.

"He says he has spent the day cleaning for our arrival, but the living room is still an extraordinary muddle. In the center, incongruously, is a huge tree stump; on the walls old pictures recalling the glories of imperial Russia contend in cramped space with bric-a-brac and childish daublings; over everything hangs the pervasive smell of cats. The balcony, which should be a pleasant place to contemplate the view, is piled high with a mountain of potatoes which have overwhelmed their container– a large plastic bath.

"All this," says Manahan, "is how Anastasia chooses to live."

Although he's rich, and although this is America, the potatoes remain because his wife feared being hungry in the winter. The stump recalls her time in the Black Forest, and the cats– well, the cats are there simply because "Anastasia's life is centered on her cats."

(Oddly, the Manahan family motto is Felis Demulcta Mitis: "The stroked cat is gentle.")

In a 1990 C-ville Review article, Overton McGehee (writing under a pseudonym) relates that Anastasia believed human souls were reincarnated in animals when they died, and animal souls were reincarnated in humans.

"When the cats were sick, Jack had to sneak them out in the middle of the night to take them to the vet," McGehee reported. "The explanation was quite simple. The cats were Anastasia's reincarnated friends. Obviously, you don't take Russian nobility to the veterinarian, even a Charlottesville veterinarian."

McGehee's article also mentions the stump. He said his uncle told him about the night Jack and Anastasia stopped to chat, and his uncle asked Jack why there was a tree stump on the station wagon roof. Jack explained that they needed to take it to the dump. McGehee's uncle offered to tie it down, but Jack declined the offer. Then he drove off slowly, careful not to tax the wagon beyond its physical endurance.

Was it the same stump? During competency hearings for Anna in 1983, the Daily Progress reported, Jack testified that Anna did not like strangers and believed that artificially heated houses spread germs and disease. A more logical explanation about the stump was supplied by a neighbor when the furnace in the house was broken.

Even though Jack was well off on paper, he didn't seem to have much cash. So he would drag pieces of wood– from limbs to whole trees– into the house and feed them into the fireplace.

But wood wasn't all that was burned there. The neighbor– like a young man who testified at a later trial– reported that if one of the 20-plus cats died, Anastasia cremated it in the fireplace. Evidently that was okay since its soul had departed.

Dining out with the Manahans must have been unusual. Summers and Mangold continue in The File on the Czar:

"At dinner in an eminently respectable country club, Anastasia wears a synthetic raincoat– and keeps it on throughout the meal. She clutches a rain hat filled with silver foil, ready to wrap leftover meat from dinner, which she scoops up and saves for those feline friends of hers."

In an article in the September 1993 issue of Lynchburg's Scene magazine, Betty Reid Page described having a strange luncheon with Anastasia and Jack in 1982: "Jack sat at the booth with his napkin tucked in at the neck of his shirt below his several chins. Anastasia ordered strong, hot tea and put 12 spoons of sugar into the cup and then poured a little at a time into the saucer and drank it."

Page added, "Anastasia ate a little of her lunch. Then she took a large handbag, opened it, and scraped the rest of the food inside. Into the bag, on top of her glasses case, charge cards and coin purse went the remains of a pork chop, mashed potatoes, gravy, rolls, and a bit of cherry cobbler." Jack, unperturbed, explained, "She's taking the food home to her cats."

But by the 1970s, neighbors on University Circle had had it with the cats– and the refuse buildup on the Manahan property.

An August 30, 1978 article in the Progress reported that six neighbors had sworn out warrants against the couple for failure to maintain clean and sanitary premises, allowing their dogs to roam, and allowing weeds and brush to grow in excess of 18 inches. And there were odors.

The article noted that two years earlier Jack had explained it all in an interview, "Anastasia sets refuse traps around the house to keep away unwanted visitors. The traps include banana peels, firewood, and other large objects."

At trial, Jack attempted to prove that he was innocent of the charge of rat harborage by showing a pristine caribou antler. He reasoned that it was a well-known fact that rodents gnaw on antlers, and that since these antlers had been stored in his basement for years with no gnawing, he couldn't be guilty of rat harborage.

The judge disallowed the motion and fined the Manahans $1,750.

"Anastasia often sits in a car and screams at all hours of the day or night," read an October 13, 1983, article in the Progress. The doors on the Manahans' unheated home remain open, it said, and "the couple's property is in poor condition, witnesses testified."

A former neighbor said that most of the screams she heard were Anastasia yelling for Jack. For some reason she always called him "Hans." One source says Anastasia let out a piercing scream in his presence, and he asked Jack what was wrong. He said, "Oh, you know those Russians– they're never happy unless they're miserable."

Despite the filth and the quirks, a letter in the Progress after Jack's 1990 death shows the reverence many felt for him. "On the afternoon of March 25, nearly 300 people crowded into the Westminster Presbyterian Church to demonstrate their affection for a great soul, Dr. John E. Manahan (as he deserved to be addressed, though he preferred to be called ‘Jack' by his many friends). Jack was always a gentleman, always courteous, always considerate. The one word that best describes him (if a complex human being can be so summed up) would be ‘kindness.'

"It will be hard to think of Charlottesville now without Jack Manahan," closed the writer, Francis W. Springer.

Jack was unquestionably a bold historian. In a wide-ranging interview with Barclay Rives in the January-March 1988 issue of Albemarle, Jack stated that he knew many of the world's great secrets. He said not many people knew that Jefferson's motto was "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God."

Another secret he revealed: "The stock market crash on October 19 [1987] was planned because that's Yorktown Victory Day. That's the main day of the year for me. I always go to Yorktown, but I didn't get there this year." The connection with the stock market crash was not explained, like so many things in Jack's life.

Jack's specialty, though, was genealogy. He had 25,000 books on the subject, perhaps the largest collection on the East Coast. McGehee's 1990 article provided an example of his encyclopedic knowledge. Jack related the 18th century story of a frightened three-or four-year old boy abandoned on a dock near today's present-day Hopewell.

The mysterious boy was able to communicate little beyond the fact that he was named Pietro Francisco. He was raised by the family of a Cumberland County judge and grew up to fight in the American Revolution, including many battles against Colonel Banastre Tarleton's raiders. He grew so big and was so heroic that he was dubbed "the Virginia giant."

"Many years later," McGehee wrote, "the old war hero was honored with the post of Sergeant of Arms at the Virginia General Assembly. Still no one knew from whence he came, not even Francisco himself. That knowledge had to wait until Jack Manahan came along.

"[Jack] went to an island in the Azores where many people are unusually large. Sure enough, there was a record of Pietro Francisco, who had vanished at the age of four. Today, buttressed by Jack's research, Portuguese-American communities celebrate Peter Francisco Day, in honor of the first Portuguese-American hero."

Jack became interested in Anastasia, 21 years his senior, through Gleb Botkin, son of the Czar's family physician. Botkin's father had been murdered by the Bolsheviks along with the royal family in 1918. Botkin had known Anastasia as a child and supported Jack's wife's claim that she was the Czar's daughter. He escaped from Russia during the early months of the revolution and came to New York to be near his children. Botkin founded "The Church of Aphrodite"– which was more philosophy than religion– and gave himself the title of Archbishop.

When his house in New Jersey burned, the Reverend Botkin moved to Charlottesville to be with his daughter, Marina, and he served as Jack's best man when Jack married Anastasia.

Former journalist Rey Barry has written that Jack was entranced with Anastasia's story– which Jack came to believe and champion– and that was his main reason to marry. Her interest may have been that she wanted an identity and a way to stay in this country because her visa was set to expire on January 13, 1969. Jack apparently loved and took good care of her for as long as he was able.

Anastasia told many stories about her history. She long insisted that her many abdominal scars came from Bolshevik bullets and bayonets. As she grew older in Charlottesville and was contending with severe arthritis and anemia on top of what appeared to be mental problems, she recounted a new version of the story of her family's survival and her own miraculous escape. Each member of the family had doubles, she said, and they were the ones executed in 1918.

"Her story, even her champions concede, is made less believable and appealing by her obstinacy, contradictory evidence, and paranoia," wrote the late Libby Wilson (Elizabeth Zintl Wilson) in a front page Progress article in 1983.

That year, Anna's condition had worsened such that in October, when both of the Manahans were found suffering from Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the living room of the University Circle house, a Charlottesville judge appointed a legal guardian for her, and he had her admitted to the University's Blue Ridge Hospital psychiatric ward. Jack was able to take care of himself but not her.

Then, on Tuesday, November 29, 1983, the story of Jack and Anna took a bizarre turn: Jack abducted her from the facility.

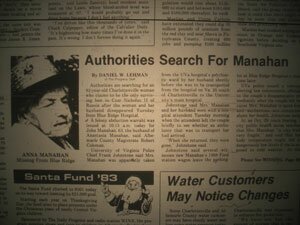

Once again, the story of a missing princess roiled the media and rekindled interest in the Anastasia legend. "Authorities stymied in search for Manahans," read one Progress headline. Three days later, Anna and Jack were found living in the beat-up blue station wagon parked in front of an abandoned Amherst farmhouse screened from Route 29 by trees.

The station wagon had broken down, and Jack had been walking back and forth between the car and Pappy's restaurant in Amherst where people had become suspicious and called the police. Even though it was December, the deputy who drove them back to Charlottesville said he had to keep the windows open because of the stench– the enfeebled Anna had not had the use of a bathroom. Jack said he abducted her because he was afraid she would be stuck in a mental institution. A source alleges that Jack paid an attendant at the hospital $1,500 for assistance in spiriting his wife away.

Two months later, Anastasia died of pneumonia at Martha Jefferson Hospital. Jack said she was "just worn out." A friend says Jack went on and on at her funeral at the University of Virginia chapel about all her "royal" friends who knew she was Anastasia but had let her down. Her remains were cremated and sent back to Castle Seeon in Bavaria where she once lived. She also has a headstone near the Manahan plot in the UVA cemetery.

Up until the day she died, February 12, 1984, Anastasia had never been able to prove she was a Romanov. So there was nothing to inherit from Anastasia. Jack, however, had inherited various properties after his parents died in 1966, including Fairview Farm near Scottsville, a 660-acre estate including an elegant manor house, buildings, farm equipment, and cattle. It became the source of many headaches.

In a signed but undated document filed in the basement of the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library, Jack recites the "untoward happenings" that occurred at Fairview between 1966 and 1982. He stated that 33 people lived on the farm until 1972, and 15 people lived there until 1982. During the period from '72 to '82, the house and farm were vandalized and burglarized. Valuable antiques, furnishings, farm equipment, and garden ornaments were stolen. Timber was cut without permission, and his dogs were killed. He said that hardware was ripped from doors and window latches, and commodes, gates, and bedding were stolen.

"To date 41 of our dogs are missing without trace of body," Jack wrote. "Twenty more have been found dead– all under mysterious circumstances. One lived with two bullet tracks and one thirty-aught six bullet removed by the veterinary at a cost of $78." He also had problems with the Confederate Angels motorcycle gang who came out from Richmond to hold wild parties and vandalize the property.

Since his family had owned the farm for many years, there are people still living in and around Scottsville who remember Jack as a child and throughout his life. At a lunch at Lumpkins Restaurant, six people gathered to share stories about Jack. ("They have good food, and it's stylish," Jack was quoted in the 1988 Albemarle article.) For almost two hours the group swapped interesting memories. Some were funny, some sad, and some were insightful about the ways Jack was unique.

Jack's father, the UVA School of Education Dean, was said to be an autocratic, aloof man who wasn't well liked, even by some fellow faculty members, and one in the Lumpkins group said the dean was disappointed in his son. Another said Jack's father was very tight with money and told him he was leaving everything to Jack in trust because Jack didn't know how to manage money.

Jack's mother, however, was just the opposite. She was "an elegant, lovely lady– kind and caring– not like his father," one of the lunchers noted. She evidently served as a buffer between Jack and her husband. One member of the lunch group said Jack collected butterflies when he was young, but added, "He wasn't effeminate."

They said Jack gave "tea parties" at Fairview where people came and stood around and chatted as though they were at a normal tea party– except that instead of tea and scones, Jack served Kool-Aid and store-bought cookies.

Virginia Lumpkin recalled one Christmas Eve when Jack came into her restaurant. For some reason, he had to go back out to the truck to ask Anastasia something. She said she heard Anastasia cussing Jack with words she couldn't believe. But when Anastasia saw her, she immediately smiled and said, "Hello, Mrs. Lumpkin," in a most pleasant and polite manner.

One in the group was a neighbor of Jack's who reported the trouble she and other neighbors had with Jack's cattle getting out and causing significant damage to her lawn and formal gardens. Even though she was fond of Jack (she had known him most of his life), she finally had to take him to court. Jack didn't show up at the first or second court dates, and when he did finally appear, he asked during the middle of the proceedings if he could go out and check on his wife who was sitting in the truck. The judge allowed him to leave– but Jack didn't come back.

When the trial resumed at a later date, Jack interrupted so often that he had to be told he couldn't speak unless it was his turn. The aggrieved neighbor had asked for $1,120 in damages, but somehow it was agreed that $800 would be an acceptable compromise. The neighbor said Jack came by later when she wasn't home and slipped a check under her door with a letter of apology about the cows.

But the saga continued. Although Jack ultimately had to sell the cows, actually herding them was another matter. A group assembled at Fairview to round up the cows and asked Jack where they were. Jack thought for a moment and said, "My cattle go around the farm in a clockwise fashion. On Friday, they were over there [pointing]. This is Tuesday, so they should be over there."

Even though they ended up not being at the designated spot, the cattle were finally rounded up and sold.

During the period from 1985 to his 1990 death, Jack's life continued to be punctuated by the problems at Fairview. Many in Scottsville remember picking Jack up on the Belmont Bridge and giving him a ride south on Route 20. He usually had a large bag of dog food for the dogs in the country.

A Progress article relates that the county dog warden had complaints about 28 wild dogs that threatened people and chased livestock and that he was authorized to kill dogs that did not have licenses or shots. The warden said it was difficult to get in touch with Jack because he didn't have a telephone. "The best way to find him," the warden was quoted, is to "go along VA 20 where he's often hitch-hiking."

An elderly lady from Scottsville– the epitome of proper Southern manners– relates a tale of her own. She says she stopped and offered Jack a ride. Jack came around to her window and looked at her and said, "I don't know you. I'm not riding with you."

An article in the Progress on September 17, 1987, related the story of a 103-year-old tenant being sued by Jack for back rent. Elbert Radford said he was born on Shakespeare's birthday – April 23– in 1884. He said he paid Jack $100 in advance in July. The case was continued because Jack didn't show up. It said he had been hospitalized for stress since a fire had gutted part of his mansion. He apparently suffered a minor stroke as a result of the stress.

Jack's love of history was matched only by his peculiar relationships with women, and not just Anastasia.

In a court battle over his will, an article in the Progress on June 10, 1994, stated "Neuropsychiatrist Gregory O'Shanick of Richmond testified that Manahan had a history of psychotic delusions that began in 1944 when, as a 24-year-old, he was discharged from the Navy for pursuing an 18-year old girl from a prominent Tidewater family, ostensibly to create worldwide religious peace."

His marriage to Anastasia seemed to be more about his interest in proving she was Czar Nicholas II's daughter than in acquiring a wife, but his fantasy of marrying Althea Hurt is stranger still. Daughter of one of Charlottesville's top developers, Hurt renewed her friendship with the widowed Jack (whom she had known since childhood) shortly after Anna's funeral in 1983 by offering, trial testimony showed, to be his "business partner." But Jack seemed to want more.

In 1986, Jack had wedding announcements printed proclaiming Althea to be "the true Czarina of the Russias." The cards showed that he intended to marry her on July 4, 1986, on Monticello's South Portico. Jack gave these cards to many people, including anyone who stopped at the intersection of Rt. 20 and James River Road in Scottsville. He also mailed invitations to Ronald Reagan, Mikhail Gorbachev, Emperor Hirohito, and the Pope. Although Althea was not a part of the marriage plans– she had turned down his proposal– their friendship endured.

Perhaps one of the strangest stories about Jack occurred after his death on March 22, 1990. His last will, made in 1987, left the vast majority of his estate to Hurt. But Jack had several cousins, three of whom contested the will. The 1994 trial saw 60 witnesses and lasted nine days.

The audiotape created by the Michie Hamlett law firm for the express purpose of heading off a challenge was supposed to be the centerpiece of the defense. However, neuropsychiatrist O'Shanick testified, according to the Progress, that "Manahan's repeated digressions on tape– each one longer and less related to the subject at hand– show he was not functioning normally."

After an emotional closing by lawyer Debbie Wyatt, alleging that Hurt exerted "undue influence" on the old man, the jury ruled the will invalid. But a month later, Judge Henry D. Garnett, sidestepping the issue of "undue influence," overturned the verdict because, he said, there was no evidence of fraud. In March 1995 the Supreme Court of Virginia sided with the Judge in overturning the jury's decision. Having already acquired the houses on University Circle, Althea Hurt now became Czarina of all Jack's property.

Shortly after that trial, interest in Anastasia exploded. The Russians conducted tests on the recently exhumed bones allegedly belonging the murdered royal family. Someone wrote a book alleging that the Czar had secreted a fortune. Anyone who could prove to be heir to Anastasia might claim it.

Back in the U.S., two separate DNA investigations began. One was pushed by a Northern Virginia man who had married Gleb Botkin's daughter. Another began when a lock of Anna's hair was found in books sold after Jack's death to a Chapel Hill, North Carolina bookstore.

On October 5, 1994, Dr. Peter Gill, who had traveled to Martha Jefferson Hospital from England to shave a few slices of intestinal tissue taken from Anna during an operation, announced at a press conference in London that Anastasia's DNA did not match the bone samples of Tsar Nicholas II or Empress Alexandra, or a blood sample from Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, grandson of Alexandra's oldest sister, Victoria.

While Anna Manahan's supporters shook their heads in disbelief, two aspects of Peter Gill's research had even more painful repercussions for the believers. The intestinal DNA matched the DNA profile isolated from the hair sample at a Pennsylvania State lab. Furthermore, the sequences also matched a relative of Franziska Schanzkowska, a Polish peasant woman who went missing around the time "Anastasia" appeared.

Bill Tucker is a retired writer who lives in Lynchburg with his artist wife.

I spent every Saturday for a year saying, 'Give these away, throw these away, sell these," says Charlottesville bookseller Sandy McAdams, who helped clean up #35 University Circle, above. "There were just piles and piles of books. The ones on shelves were fine, but you couldn't get in the door– five rooms filled with books with cat sh*t on them– thousands to give away, thousands to sell, thousands to throw out."

PHOTO BY ERIN HEISTERMAN

The Virginia Supreme Court upheld Jack's bequest of this 660-acre Scottsville-area farm to Althea Hurt, despite the presence of an audiotape on which Jack mentions that "the Hurts seem to be agreeable" to his will, a digression about kissing Hurt while watching a house fire on University Circle, and the jury's verdict nullifying the will.

PHOTO BY ERIN HEISTERMAN

That's the real Anastasia on the right in this photograph of the Romanov women, all of whom were supposedly executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

ARCHIVAL PHOTO

Newspaper photographer/columnist Rey Barry asked each of the newlyweds to pick an object that represents the spouse. Anna chose an invitation to Richard Nixon's first inaugural; Jack picked an engraving of Czar Nicholas II, his supposed late father-in-law.

PHOTO BY REY BARRY

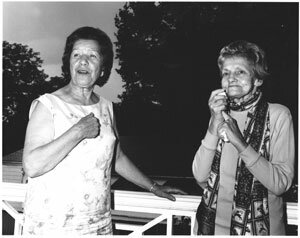

Maria Rasputin– yes, daughter of Grigori– visits Anna in Charlottesville shortly after the marriage, declares that Jack's wife recalled things only the real Anastasia would know, such as Maria's dressing as a Red Cross nurse... and then just as promptly declares Anna a fraud.

PHOTO BY REY BARRY

The three-day hunt for the "kidnapped" Anna ended in an Amherst farm field in 1983.

DAILY PROGRESS CLIPPING

#