COVER- An uncommon past time: The hardships of the simple life

Logan and Heather Ward were having a tough time brewing their coffee. Logan split firewood for the wood stove as Heather ground beans with a cast iron grinder. But after an hour or more of futile flailings at flaps and dampers just to get the stove to draw so the water could boil, the Shenandoah Valley couple were still soldiering on with empty mugs.

Logan and Heather Ward were having a tough time brewing their coffee. Logan split firewood for the wood stove as Heather ground beans with a cast iron grinder. But after an hour or more of futile flailings at flaps and dampers just to get the stove to draw so the water could boil, the Shenandoah Valley couple were still soldiering on with empty mugs.

Why didn't they just zip out to a coffee shop? The Wards, Vanderbilt graduates, recent New Yorkers, technology-savvy and cosmopolitan, couldn't go to Starbucks because they were living in an experiment of self-imposed time travel.

Before their voyage back in time, the Wards could be considered typical fast-track New Yorkers: good looking, well-educated, urbane, curious. But like other young Manhattanites, they sometimes felt that their lives were out of control: too much rushing, too many carry-out dinners, too little time for each other. More than anything else, they considered themselves slaves to technology. And the strain on their marriage was worrisome.

"Like a lot of couples," says Heather, "we weren't aware of how poor our communication had become or how little of our lives we were really sharing. We were feeling the symptoms, but couldn't put our finger on the cause. We knew that things could be better."

And so after a particularly stressful and unproductive day in the year 2000, Logan hatched a scheme that he thought might help make things better: they would leave the world of cabs and lattés, of Gmail and health clubs, and return to what they thought would be a simpler life– but not the simpler life of the hippy '60s, or even the optimistic naiveté of the post-World War II '50s. They decided to live in 1900.

A beautiful brick house at foot of the mountains in rural Swoope, about 10 miles west of Staunton, became the Wards' time machine. After months of preparation and research– and several delays– on June 12, 2001, the Wards and their two-year-old son, Luther, took up residence in 1900.

Much like the back-to-earth movement in the 1960s and '70s that was fueled by many of the same concerns that troubled the Wards, the couple primarily sought to reconnect with the earth. But they found that living as Swoopians had done in 1900 made that connection more visceral than they ever imagined.

Logan had had some experience roughing it, having taught school for a year near Lake Victoria in western Kenya. And after he and Heather married– they had met as students at Vanderbilt– the couple spent 18 months traveling and doing volunteer work in Ecuador. Back in New York City, they had creative jobs, he as a freelance writer for National Geographic Adventure magazine and she as a researcher at New York's Vera Institute of Justice, a think tank.

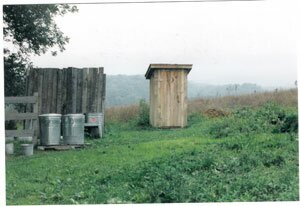

In addition to shucking obvious modern conveniences like electricity, phones, cars, and indoor plumbing and central heat, the Wards were going to learn to live without news magazines, vitamins, sandals, and even personal items like safety razors and tampons.

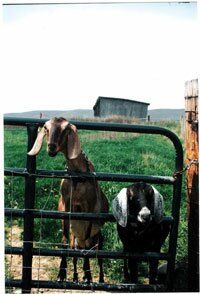

In a recent book detailing their experience, See You in a Hundred Years, Logan explains the frustration of fumbling over the harness straps of their workhorse, Belle, of blistering his hands on rudimentary garden tools, and Heather's carpal tunnel woes from hand-milking two Nubian goats who provided the family's milk.

Water– obtaining water, using water, conserving water, and disposing of water– became a daily preoccupation. Without the sublime luxury of modern plumbing, the Wards had to pump and carry every bit of water they needed in the house. In a particularly revealing chapter, Logan describes his first "splash bath" using a "soap bar, a bucket of water, a rinse cup, and a gingham table cloth for a towel" in a high-sided oval livestock tank behind the house.

"Because there was no terry cloth in 1900, bathers dried themselves with flat fabrics such as damask," he writes, mentioning the 1897 Sears catalog, which shows a man patting his face with what Logan likens to a dining-room curtain.

"I dip the cup into the frigid well water, raise it above my head, and pour," he writes. "I yelp and shiver." Life on the farm is rough.

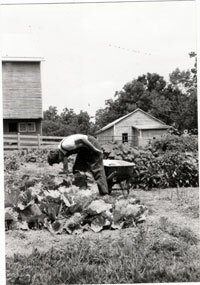

Feeding themselves, however, was the greater challenge. Having stocked up on the dry goods that would have been available to a typical 1900 family from a general store– coffee, tea, sugar, oatmeal, rice, and baking powder– they set about trying to cultivate a garden. But because unavoidable complications and delays had pushed their start date into June, the first year's crop was compromised. Without modern chemistry's pesticides and insecticides, the late garden lay vulnerable to every bug and blight, and a mid-July drought threatened the entire crop.

Ward writes that the accumulating pressure of a growing toddler's demands, the drought, the heat, and the back-breaking labor began to make the couple question the wisdom of their belief that a trip back in time would create intimacy and peace.

And not everyone was impressed.

"I hear you pulled your well pump," said one skeptical neighbor.

"It's a good workout, pumping your own water," Logan feebly replied.

"Let me get this straight. You took your indoor toilet and made it an outdoor toilet?" marveled the neighbor– before erupting in laughter.

Their food wasn't growing, so when another neighbor arrived with a gift of a tin of cherries, the Wards gorged on the unexpected treat. An invitation to a nearby wedding meant a chance to socialize. And a chance for beer. After all, that's something that was plentiful in 1900.

When the rain finally came, eight weeks into the project, the worry about food lifted, and Logan and Heather seemed to be hitting their stride. The joys they had imagined during their New York reveries began to materialize: black night skies full of countless stars, the pleasure of before-sleep reading without interruptions by phone or the buzz of radio or TV, a growing closeness in their shared sense of accomplishment and increasing competence.

Still, the food wasn't exactly bountiful. His wife is a vegetarian, and Logan decided he was not suited for slaughter (although he pens a graphic scene about chopping a few roosters for a neighbor). "Meals," he writes, "were pretty monotonous– oatmeal for breakfast and lots and lots of cabbage."

Logan explains that one of the most jolting aspects of the early days was that, without any kind of radio or music-machine, they were left with the soundtrack of their past lives in their minds. And his mind seemed stuck on UB40's early '80s hit, "Red Red Wine."

But an unimaginable world event was about to disrupt the soundtrack. Less than three months into 1900 came the signal horror of another century: September 11, 2001.

Neighbors who knew the Wards had lived in New York City so recently quickly arrived to report news of the coordinated attacks. Their first impulse was to abandon the experiment and try to contact friends and family.

"How can New York be reeling from death and fiery destruction," Logan writes, "when here all is innocence and calm– chickens clucking in their nests, cats trailing me for milk as I clink down the path with a frothy pail, Luther jabbing a spade in the dirt?

"Rather than calling or watching TV, we stick to our humdrum routine and watch the mailbox. What's the worst that can happen?... I get by without the crutch of technology, the false sense that minute-by-minute news coverage or phone contact puts us in control."

Today Logan, 41, recalls how those September events prompted lots of people in America to reevaluate their priorities. "But we had already done that," he says. "It reinforced what we were doing, made us feel that maybe we had made a sensible decision to go and learn skills.

"Although initially we felt so helpless, as time passed, we realized that in a way we were doing something very meaningful: we had nestled ourselves in a community, and we were focused on our family and our immediate well being.

"Many people described the events and the feelings of that time as 'apocalyptic,' and we realized that we were honing skills that might come in handy for survival some day."

Those skills ranged from inventive conveyances to shaving with a straight razor. After a neighbor built him a horse-pulled sledge, he quickly figured out how to ride behind Belle standing up. "It was a real breakthrough for me in terms of feeling comfortable driving the horse," says Logan. "I grew up riding skateboards and knowing nothing about horses, so I figured this was perfectly appropriate."

But mastering 1900-style grooming was a little tricker– and bloodier.

When a Gillette Mach3 arrived in the mail as an unsolicited promotional gift, he was tempted. "Just use the Mach3," a voice in my head says, "and end the bloodshed."

Their only concessions to modern living were two safety valves: they bought sunscreen lotion for Luther (risks of sun damage are greater today than in 1900), and they kept a line alive in the house so they could plug in a phone in case of an accident. One other "slip" into modernity: Heather joined Logan in voting in November elections even though women in 1900 were still 20 years away from suffrage.

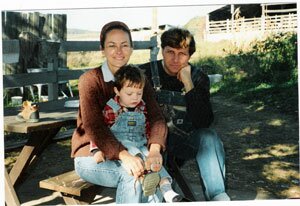

So how do we have photos of the family? Visitors and relatives were allowed to bring cameras and take their pictures.

Harry Uram of Loudoun County knows something about living in the past. As a re-enactor with the 8th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, he often dons the clothes and engages in the activities of Civil War soldiers of 1860.

"They were a different breed back then," he says. "They were a lot stronger. Life was extremely tough in 1860; unfortunately, in America we confuse civilization with indoor plumbing. We take a lot of things for granted."

He applauds the Wards' attempt to experience life as our ancestors did, but he doesn't wish he lived in 1900. "We do long marches, but we do it for one or two nights, and then we go back to our SUVs and air conditioning," he says.

And echoing the Wards' experience, he adds, "Those boys went to war to escape the back-breaking dawn-to-dark work on a farm for no pay. They didn't have iPods. Their lives were hard, boring. They did it as much for excitement as for a cause."

But for the Wards, over the fall and winter, as their competence grew and the slower pace of life became a comfort instead of a chafe, the couple found the growing intimacy they had lost track of in the hurly burly of big city life.

They found tricks to improve their crop yields, notably emptying the family chamber pot around the corners of the corn plot to ward off thieving raccoons.

By Thanksgiving, when Logan's parents arrived for a visit, Heather had put together a feast– corn pudding, rosemary-flecked potatoes, pumpkin pie, and– of course– turkey seared to perfection inside the smoky firebox of their wood stove.

Another sign of the success at creating intimacy was their decision to conceive a second child. Because Luther's birth had been difficult, necessitating an emergency C-section that saved Heather's life, they had agreed not to attempt a pregnancy when they were living in 1900. But as their experimental year wound down, they made a decision "to join the birds and the bees," and they put away the historically accurate condoms ("made of sheep gut or thick, reusable vulcanized rubber").

"While the new season is firmly in place, Heather and I find ourselves in transition," Logan writes toward the end of his book. "Stirring within us is a mixture of excitement and trepidation over the end of our project. In many ways, staring into an unknown future, with its endless possibilities, is more frightening than facing a year of living without modern conveniences."

Today Logan describes the options he and Heather had considered at the beginning of their year in the past.

"We had three choices," he says. "We could go to a place and do the project and leave; we could go buy a property and do the project and leave; or we could buy a place and stay.

"It became clear to us early on that we wanted to stay, and certainly by the end of the year, it was our goal to stay put on the farm permanently. We had a 20-year plan."

And so on June 12, 2002, they came back to the modern world expecting to live there happily ever after. The last day had been business as usual: milking the goats, pumping water, cooking over the wood stove, cleaning, shoveling manure. But they began to prepare, as he writes, for "re-entry" by trying to revive their old Ford Taurus (removing animal nests), eating early English peas from their garden, and trying to control both their excitement and their anxiety about the journey forward in time.

And two weeks after returning to their own century, they threw a party for the neighbors whose help and friendship had been one of the most enduring gifts of the experiment.

Peggy Roberson, a close neighbor across the road, explains the effect of the Ward's presence on the community.

"At that party they gave when the year was over," she says, "I recognized the truth of what he said about building a community. I told Logan, 'You two helped the community as much as we helped you. Through you, I met people I had never known although I've lived here for so many years.'

"Everybody was together that day, just celebrating being a community."

Soon after rejoining the modern world, however– after having the electricity and the phone turned back on, the indoor plumbing reinstalled, and resuming enjoyment of other amenities of contemporary daily life– the tension of trying to blend old and new mounted.

"Reality hit in the sense that we needed to make a living," Logan says, "and we also realized that we were trying to straddle our two existences, living close to the land but integrating back into the 21st century."

Finally the pressure of renovating the house, resuming his freelance writing career– which meant "hustling articles, working on the book proposal"– and preparing for the birth of their second child, was too much, he says. "We realized that to stay on the farm, we were going to have to commit to a level that we hadn't prepared for, to figure out a way to make the land pay for itself.

"And we didn't know any way to make the farm pay."

Today, after putting the farm and its 40 acres into a conservation easement and selling it to a new owner who uses the place to nurture rescued horses and dogs, the Wards are comfortably ensconced in nearby Staunton. Logan Ward is president of the Historic Staunton Foundation board of directors, and Heather has just begun a job as director of international programs at Mary Baldwin College.

Further evidence of their sense of belonging is Heather's willingness to engage in one of the area's biggest civic brouhahas: joining a group protesting the controversial "weekday religious education" program that teaches Bible studies to elementary school students.

"I felt like I was speaking for a lot of people who were reluctant to speak, foreign nationals and people of other faiths like Quakers and Unitarians, who were more shy or weren't willing to take on the locals," she says. And she downplays any notion that she was an outsider challenging the local school system

"We had lived here four years," she points out.

"If there's one thing we learned from out project," she says, "it's that to be a part of the community you just become a part of the community. I never felt like an outsider."

So, the big question. What did they learn? Was life better a hundred years ago?

Logan thinks a moment before replying.

"It's like architecture," he says. "In life, as in cities, you want the best of the old and new. With preservation, we can have them both. We cannot control technology, but we can enjoy the gentle reminders of the power of the past."

Rosalind Warfield-Brown is the Hook's copy editor.

Logan Ward found a period-appropriate pickup truck after a neighbor built him this sledge for hauling things behind his draft horse, Belle. He quickly learned to ride standing up, a practice a friend's child dubbed 'turf-slurfing.'"

PHOTOS COURTESY LOGAN WARD

Nubian goats Sweet Pea and Star share the barnyard with the Percheron, Belle.

Indoor plumbing was not an option in Swoope in 1900.

Logan Ward picks some of the cabbage that became a daily diet staple.

The wood-burning cookstove on which Heather Ward prepared meals and canned the garden's bounty

Luther, Heather, and Logan Ward c. 1900.