COVER- Patented medicine: Trail of money follows trail of tears

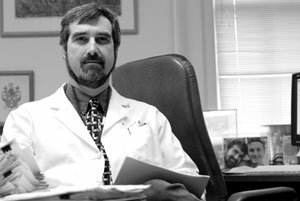

Dr. Bennett is one of many UVA inventors whose pictures grace the walls of the UVA Patent Foundation office in the Lewis & Clark building downtown.

COURTENEY STUART

Baseball legend Lou Gehrig immortalized himself in 1939 as "the luckiest man on the face of this earth." Over 70 years after Gehrig's heart-breaking speech, however, there's precious little luck for sufferers of the fatal disease often bearing his name. However, a local doctor's drug discovery– combined with the an entrepreneurial strategy by an up-and-coming office affiliated with the University of Virginia– may change the outlook for patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

As the drug, dexpramipexole, begins serving up good news for UVA in the form of millions of dollars in licensing and royalty fees, it comes with some painful baggage in the form of 15 ALS patients who saw their access unceremoniously snatched away.

Gatorade to Taxol

The University of Florida has made more than $150 million from Gatorade, the sports drink invented by one of its doctors in 1965. Stanford University continues to live large off of a little invention known as Google. And a cancer drug called Taxol brought Florida State University an estimated $400 million over the last 25 years.

In recent years, UVA has begun seeing glimmers of this kind of "translational" success, when basic research at a university ultimately finds a commercial application with its patent foundation becoming one of America's top licensors. Along the way, however, there's been controversy–- life-altering controversy.

As detailed in the Hook's February 24, 2005 cover story, "She's dying: His drug could save her," a UVA neurologist named James Bennett discovered a compound sitting on the shelf of a German laboratory and theorized that it could lessen some suffering. After testing the compound for eight weeks on mice with no ill effect, Bennett signed up 15 ALS patients in the summer 2004 for a Phase 1 study to determine its safety in humans. The subjects all tolerated the drug with no side effects. They did, however, report that their symptoms seemed to be slowing and even, in some cases, improving.

Patient Mary Jane Gentry, for instance, reported regaining movement in her right hand. Another patient reported being able to articulate a few words– something she hadn't been able to do in months. And others said they'd managed to stand up for the first time in weeks.

The early excitement, however, quickly ran into the rules of medical research where Food and Drug Administration protocols must be followed and where the scientific method trumps any individual's desires. At the end of eight weeks, citing "safety of the research volunteers," UVA officials pulled the plug on the study. A panel claimed the animal testing should have lasted longer and that any positive outcomes were likely manifestations of the "placebo" effect, the power of positive thinking.

Obviously, the move didn't sit well with the terminally ill patients, at least one of whom called the move "inhumane." Mary Jane Gentry, a woman who only months before her diagnosis had been working as a nurse and wielding power tools in home improvement projects, lost her mobility. By early winter 2005, as the disease took its toll, she was confined to a wheelchair. And within months, she was admitted to a nursing home where, she knew, she'd spend her final days.

Five years after his wife began reporting progress in the unceremoniously terminated drug study, Preston Gentry still considers himself angry.

"It was very frustrating," says Preston Gentry. "I think that if a person has a fatal disease, and this is an option that they choose to take, they should be able to sign a waiver and say, 'I'll take the consequences, I won't sue anybody.'"

Ten months after UVA pulled the drug, in September 2005, the FDA granted permission for the original patients to continue taking it on a "compassionate use" basis. But it was too late for Mary Jane Gentry who had died three months earlier.

"I felt like they were playing God," Preston Gentry says of the committee that enforced the rules.

However, if the first patients were dying, the drug would soon find new life.

'Very encouraging' signs

In 2006, with Phase I studies showing it safe for humans, Bennett's drug was licensed by a small Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company called Knopp Neurosciences which began shepherding it through larger scale Phase II studies, which began to examine the drug's efficacy.

The results were "very encouraging" says Knopp CEO Dr. Michael Bozik, citing the drug's apparent ability not only to extend life but to extend quality of life by approximately 33 to 50 percent. If the average patient with ALS lives three years beyond diagnosis, that could mean an extra year of time with family– and time to possibly benefit from other research discoveries.

The results were encouraging enough to lure major pharmaceutical company Biogen Idec to invest and take over the costs of the Phase III studies, which are much larger in scale than either Phase I or II, with potentially thousands of research subjects.

As part of the deal announced August 18, Biogen paid $20 million in cash, bought $60 million of Knopp stock, and committed to additional payments of up to $265 million based on results of the future research which will take place around the United States and in several as yet unnamed European companies. If the drug reaches the market, Biogen will also pay "tiered, double-digit royalties" to Knopp on worldwide sales, according to the announcement. All this means that UVA and Dr. Bennett, which have already benefitted financially, will continue to do so.

According to the interim executive director and CEO of the Patent Foundation, that's thanks to the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, a federal law which granted permission for publicly funded universities to hold patents and earn royalties but required them to pay the inventors– typically research faculty– a minimum of 15 percent of the royalties and to funnel remaining funds into future research being conducted at the school.

At UVA, inventors receive royalties on a sliding scale. If the school collects under $100,000, the inventor receives 50 percent. That number drops to 30 percent on royalties up to $300,000 and is halved again to 15 percent for royalties of over a million dollars.

At this point, says the interim director Miette Michie, Bennett's drug has already brought the school between $300,000 and $999,000 with Bennett receiving 25 percent of those royalties. Michie declined to provide a copy of the contract between the UVA Patent Foundation and Knopp. Because the Foundation is a nonprofit and is separate from the University, it is not subject to Freedom of Information Act requests.

UVA would undoubtedly win if dexpramipexole were to follow a path similar to the cancer drug Taxol, which is held up in university research circles as the standard bearer of a translational success.

It started back in the mid-1960s when researchers discovered that the bark of the Pacific Yew– a scrubby, slow-growing tree native to the West Coast– contained cancer fighting properties. The problem: extracting the active ingredient would require decimating the tree population. However, one of those early researchers– Robert Holton– working about a decade later at Florida State University– discovered a way to synthesize the active molecule. The laboratory-made drug– Taxol– became one of the most effective and successful cancer treatments in medical history, with annual sales peaking at $1.6 billion in 2000. Florida state reaped more than $400 million in royalties–- including $67 million in 2000 alone–- before the patent expired. Holton became a rich man– albeit one who continued to work full time as a researcher.

Cashing in?

The subject of medical researchers and universities getting rich off research is a sensitive one, particularly since human test subjects are involved and the risk for ethical conflicts are high. But the Patent Foundation's Michie defends researchers against anyone who would claim they're too eager to cash in.

"Faculty do not become faculty if they're money hungry," says Michie, citing the fact that other career paths are typically more lucrative than most professorships. Still, she acknowledges that offering a generous royalty schedule is one way to attract top talent and a way to encourage faculty in all departments– not just the school of medicine– to seek ways to market their research.

Gentry also says he has no problem with the prospect of Dr. Bennett getting wealthy.

"I know how much time Dr. Bennett put in with Mary Jane," he says. "If this turns out to be a good drug, he shouldn't have to worry about anything the rest of his life, as far as I'm concerned."

Gentry is less pleased at the idea of UVA reaping financial rewards after denying his wife the drug even as she and others begged for access.

"The University is riding on his coattails," he says of Bennett. "They get the free ride, he's doing the work."

The UVA Patent Foundation, an independent nonprofit that is the safekeeper of much of UVA's intellectual property, has seen its ranks grow from just three employees a decade ago to 20 currently on staff. And the school has created a new high level administrative position dedicated solely to bolstering researchers' ability to market their inventions.Mark Crowell, UVA's executive director and associate vice president for innovation partnerships and commercialization– a position created this year– points out that without the University's involvement, many discoveries made by faculty would never see any commercial success. Recently, the Patent Foundation announced that on an adjusted basis in 2007, UVA ranked fourth in "deal flow" and second in "invention disclosures" among its peer institutions.

"One of the things I will be undertaking is to be a bit more aggressive at reaching out within the institution," says Crowell, noting that many professors aren't even aware of the potential to patent and commercialize their research– and medicine is not the only area such possibilities exist.

"I'm kind of a scientific matchmaker– a yenta," jokes Crowell, recalling one of his favorite commercial successes while he was doing similar work at University of North Carolina: a web-based course developed in the language department to teach health care workers how to communicate with Spanish speaking patients.

"Most people would tell you, you don't do this because it makes you rich," says Crowell, again pointing out that all revenue that comes into the University is reinvested in research. "You can't go buy the president an airplane or invest in a stadium," he says.

All the talk about money and about who deserves it or doesn't at UVA may be premature anyway, according to one of the country's leading ALS researchers, Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Rothstein– who is overseeing a dexpramipexole trial at his site– says dexpramipexole isn't the first ALS drug that's shown promise in Phase II studies, and history suggests it's dangerous to raise hopes up before the final Phase III studies are complete.

"When Riluzole was first discovered, it had remarkable efficacy in Phase II studies," says Rothstein, citing the only medication currently available for ALS patients. But in the end, while Riluzole was eventually approved and is frequently prescribed, it has only a "very slight efficacy," says Rothstein.

Bozik agrees, and says Riluzole's only effect is a slight increase in life span–- several months at most–- without any corresponding increase in quality of life.

"It's never been shown to have benefit of strength or motor function," says Bozik, adding that dexpramipexole has shown the potential to both extend life and slow progression of symptoms. "It's about keeping patients walking, talking, breathing and eating, longer and better."

Bozik says Knopp will remain involved in the Phase III studies, but thanks to the deal with Biogen, the company will now focus on studying why the drug works in hopes of further developing a treatment with the goal of turning ALS into a chronic disease that one can live comfortably with for years– as various medications have done for HIV/AIDS, which was essentially a death sentence in the 1980s, the early days of its identification.

Rothstein also believes that the greatest hope for ALS sufferers may lie not in a medication but in gene therapy. Already, a trial exists in which researchers are attempting to "turn off" a gene that has been associated with some ALS cases.

Other researchers are testing already existing drugs used to treat other illnesses to see if they might have an effect on ALS. Currently, Rothstein says, researchers are looking at an antibiotic called cephtriaxone that has shown some promise in laboratory models.

"We need trials in ALS, we need to keep taking shots on goal," says Rothstein, urging restraint before believing any drug currently being studied could be a magic bullet for ALS. "No matter how excited we are," he says, "I've done enough trials to know that I'll know when the trial is over."

Today

Dr. Bennett now serves as the Chair of the Neurology Department and a founding director of a Parkinson's clinic at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical School (formerly MCV) as he prepares to conduct new research on dexpramipexole's possible efficacy in treating Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, says he's delighted to see the ALS research moving forward with continued promise.

"I was very hopeful that this day would come," he says. "I couldn't be more thrilled about this outcome."

UVA will hold the patent on the use of dexpramipexole in ALS for 20 years– the maximum allowed by law– but Bennett's future studies on other applications for the compound will be patented by VCU.

Biogen expects to commence the Phase III studies in early 2011, according to Bozik, but even if all goes well, it will be a couple of years at the soonest before the compound becomes widely available. For the patients involved in the early study at UVA, who first described positive results back in 2004–- before having the drug taken away from them by a UVA ethics board–- it's too late. All 15 have died.

But for the estimated 30,000 Americans currently suffering from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and all those who will be diagnosed in the future, the news is a beacon of hope for a disease with an otherwise hopeless prognosis.

Gentry, who remarried to his high school sweetheart several years after Mary Jane's death, says he has high hopes that the drug his late wife believed in lives up to her expectations, even though she's not here to benefit from it.

"Mary Jane would be right out there in the front," he says, "right behind Dr. Bennett 100 percent."

"At a company, when an employee makes an invention, they get nothing– they might get a plaque or a lunch," says UVA Patent Foundation Interim Executive Director and CEO Miette Michie. "It's not recognized like it is in a university."

COURTENEY STUART

"This is the first drug that offers real hope for people facing down the most gruesome, grim degenerative disease that there is," says Knopp Neurosciences CEO Mike Bozik, pictured here at an August press conference in Pittsburgh announcing the Biogen deal.

ANDREW RUSSELL/PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE REVIEW

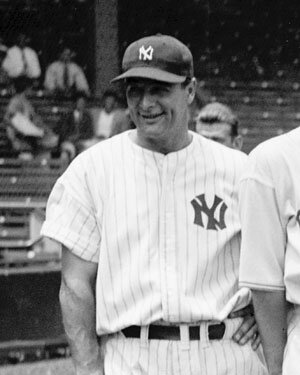

Yankee great Lou Gehrig called himself the "luckiest man on the face of this earth," despite being diagnosed with ALS, the disease that would quickly rob him of his ability to play baseball and would cause his death in June 1941, less than three years later.

Flickr/xxxxxxx

"It gave her hope, and without hope you can't go anywhere," says Preston Gentry of the drug first developed at UVA that is now heading into the final research stages. "It was very frustrating." His late wife Mary Jane Gentry is pictured above before her June, 2005 death.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"I've been fortunate to have intersected with a number of very talented and motivated individuals, particularly those who formed Knopp and stuck with it when it wasn't certain what was going to happen," says neurologist and researcher James Bennett, who is now with the VCU School of Medicine in Richmond.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The UVA Patent Foundation, headquartered in the Lewis & Clark Building downtown, is among the most highly ranked university affiliated patent foundations in the country for its success commercializing faculty research.

COURTENEY STUART

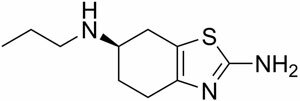

Known as dexpramipexole, the compound Dr. Bennett developed as a treatment for ALS isn't new. In fact, it's the chemical mirror image of an existing drug called Mirapex that's used to treat Parkinson's Disease by mimicking the neurotransmitter dopamine. But while both forms of the compound are powerful free radical scavengers, Mirapex, taken at high enough doses to impact free radicals, also causes extreme side effects– nausea, dizziness, even psychosis– while dexpramipexole does not.

COURTENEY STUART

#

6 comments

The roylatys should be used for subsidizing tuition or indigent medical care not marble granite and commissioned paintings. UVA wastes so much money on grandiose items.

This, will get messy

there is a lot of blame placed on FDA, yet it is often the industry, specifically Biogen, that takes forever to roll out the actual product. They have back burnered many good drugs in the past and lost billions in sales. It is hard to choose the winner from the thousands of patents filed. More than likely this drug will also turn out to be a dead end with no great royalties coming in to UVA. Everyone is so quick to want the money for themselves or program, but 100% should be put into medical research at this doctors choice, since he is likely to find more drugs for other diseases, but no doubt even after this notariety, he probably can't get funding for his next ideas and battles for grant money while UVA builds sport stadiums and snobby students whine about the tuition cost of their art degree all while protesting the low wages for janitors, unaware that they will make about the same at graduation. Don't mix the royalties if any with the general funds, put it back to save more lives.

It's great to read the comments of experts who just know that successful pharmceutical companies really don't know their business, and know equally well how other successful entities should spend their money.

I stand in awe of your brilliance.

I claim no brilliance, simply insight from researching. Biogen sold off Angiomax for very cheap and now the medicines company sells over a billion dollars a year world wide, Victor Kiam thought Velcro was interesting but not useful. My point is is that even good ideas can be slow to market (angiomax was delayed a decade by Biogen persuing other drugs and back burnering the Angiomax, it is actually a very interesting case as the medicines company missed a filing deadline for a patent by a mailing mix up by one day which the patent office allowed but the FDA didn't, costing this successful company $13 million in lobbist payouts all over waiting for the last day to file a simple extension. Far from organized, this bussiness is a real soap opera of mishaps and political whims that often leave the scientists and Universities with little.)

So Micheal Jordon was picked behind 3 other people in the 84 draft, not everyone has a future telling ability, and Biogen is no different. Each drug is a big gamble and may or may not pan out. My concern from this story is the dreamy money discussed that may or may not come true and everyone at UVA thinks how to use this "free" money in lean times. I am sure there are many programs in need of some more money, perhaps all. Just remember that medical research is what all these cancer walks and charity drives are for, to give scientists money to research possible cures since corporate companies can not afford to lose money on basic research or unproven leads. That is my point.

I have been informed by persons smarter than myself, a large group, that royalties not paid out to inventors or used for legal and operating expenses are put back into various research related projects at the university, not in the general funding.

Biogen is likely to find parrallel inventions that might be better medically and make the current patent not valuable, it tends to have multiple patents on the same subject area each with a little change in the configurations. No telling which one will have the right receptors.

In either case, those looking for lower tuitions from any of this are out of luck. Better of working on a Gaitoraide substitute with out Fructose..Cavilaide..just a hollow empty nicely decorated bottle that looks cool with no substance inside.