Penn's teller: A chance Hollywood encounter in the Omni

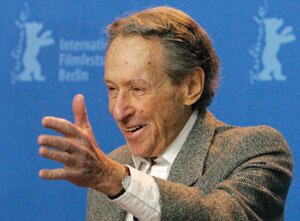

Three years ago, Penn–- who died September 28 at the age of 88-and-a-day–- received a lifetime achievement award at a Berlin film festival.

Reuters/Fabrizio Bensch

As the 23rd Annual Virginia Film Festival is about to begin, so will my 22nd stint as a Festival volunteer; but a month-ago obituary takes me back to a memorable moment from 1998.

Headed to my volunteer shift at the downtown Regal, I stopped off at Festival headquarters, a meeting room in the Omni hotel.

The food and drink table had been ransacked, and the phone was ringing off the hook as the meager staff tried to keep up with a flood of incoming questions. The only other occupants were at far end of the room.

The woman, apparently a college student, spoke into a tape recorder as she interviewed an older man. Newspapers on a coffee table drew me to a nearby couch. The man was speaking as I sat down: "When we figured out the character of C. W..."

"C.W.?" I wondered. "C.W. Moss? Michael J. Pollard's character in ‘Bonnie and Clyde'?

Suddenly it dawned on me: "That's film director Arthur Penn!"

I glanced over to verify. I recognized him from "Inside the Actors Studio," the then newish Bravo network show. As then Actors Studio president, Penn often sat in the audience during interviews.

He looked up at me and nodded. I returned the nod and continued to feign reading the newspaper paper so I could eavesdrop, but the ringing phone kept foiling my attempts.

Soon, the interviewer asked: "Why did you set "Alice's Restaurant" in a church?"

"Well— it took place in a church," he said, seemly surprised by the question. "It was a true story by Arlo Guthrie. Don't you know who Arlo is? He's the son of the folk singer–" He paused and looked over at me. "What's Arlo's father's name?"

"Woody Guthrie." I answered. He smiled and repeated my answer to her. I stood up. "Mr. Penn— would you mind if I joined you so I could listen?"

"Please," he answered while waving me over.

I crossed the room and sank into in a large upholstered chair whose voluminous arm I leaned over while sitting like a pupil enraptured by a favorite teacher. He continued answering the interviewer's questions— until her tape recorder stopped. She looked at the machine. No more tape.

"That's okay," she said, "I'm out of questions."

I piped up: "Mr. Penn, do you mind if I ask you a few questions?"

"Go ahead," he replied.

I had no idea what to ask him, but I suddenly remembered he had directed a film I had seen several times, and 27 years earlier, at the Paramount Theater.

"'Little Big Man' is one of my all-time favorites," I began. "How was it working with Dustin Hoffman?" He smiled, knowing I was alluding to the actor's infamous temperament.

"He was fine, then," said Penn. "I wouldn't work with him now, though."

"How was Chief Dan George, who played ‘Grandfather'?"

"He was wonderful, wasn't he? He wasn't an actor before that, did you know?" I nodded.

"What is the favorite of all the films you've done?"

"I've enjoyed each one in its own way. I can't say I have a favorite."

I tried to think quickly about other actors he directed.

"Have you ever worked," I blurted out, "with Gene Hackman?"

"Yes— in ‘Bonnie and Clyde," he said.

"Oh– Buck Barrow," I said, wincing as I realized I had just asked the equivalent of: "Why did you place it in a church?" Unfazed, I tried again.

"In Little Big Man, you worked with one of my favorite character actors: Martin Balsam. What was he like?"

"He was in that?" replied Penn. "What part did he play?"

"He was the snake-oil peddler who kept showing up missing another appendage each time: a leg, an arm, an ear..." Both Penn and I broke up laughing as we thought of the character brought to life by this terrific actor.

When the laughter stopped, the director's mood and look suddenly changed. He gazed off in what seemed like a wistful reverie, quietly saying, "Marty. Marty..." He paused for so long I thought I had lost him. Then he turned back and spoke in a hushed tone.

"Marty had a stroke, did you know?" he began. I shook my head in reply.

He turned away and continued. "It paralyzed his right side. It devastated him. He was so embarrassed that he quit acting."

Penn turned back to me as if to plead a point. "I begged him to come to the Actors Studio. I told him he could teach— he had so much to offer. He was such a great actor. But he wouldn't. He was such a proud man."

He looked away, and finished: "His girlfriend took him in and took care of him until the end. He died in her apartment– penniless."

Penn sat quietly, as if to gather his thoughts. He returned to the voice he had started with.

"Well— I guess I have to go to an event soon," Penn said, as the student took the hint and they stood up. She thanked him for the interview.

I stood up and thanked him as he turned towards me.

"One more question, if I may, Mr. Penn?" I said. "It's been said that most directors' films have a message or theme that run through them collectively."

"That's true," said Penn.

"What is the collective message of your films?" I queried.

"You'll have to view them all and see if you can figure it out for yourself."

Penn grinned and winked as we shook hands. I think that even as I walked away, I knew I had just experienced a magic moment.

~

Though Roger Ebert once described Carroll Trainum as a "movie lover and an expert" in an autograph on a poster, Trainum merely considers himself a film buff. He may be seen at the volunteering at the Festival— or just around Charlottesville— sporting his ever-present Boston Red Sox cap.

#