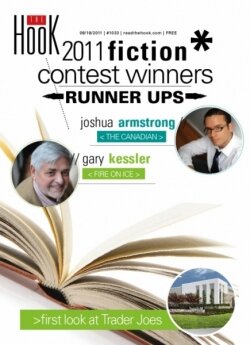

Fire on Ice

Please, God, this isn’t happening. Where did I go wrong? What did I do wrong? When did this dusting of snow become so deep?

We were struggling along the trail– or at least I hoped we were still on the Appalachian Trail. Two scouts and me. But it was hopeless. It was quite dark now. What we’d said was that if any of the teams of boys didn’t return to the Humpback Rock parking lot at the end of two hours, we’d send a team for them. They were to stay on the trail and in their designated sector. We’d come along the trail, blowing our whistles, and then we’d be sure to meet up. No problem.

It was a simple compass direction-finding exercise. We’d done it here for years and never had had a problem. Where did I go wrong this time?

Who could have guessed it could get so dark so fast, or that the snow would roll in like this? This afternoon it had been quiet along the trail. Now the wind was howling. There was no way the boys could hear us whistle. The wind took the sound completely away. Was this what fear sounded like? The whistles were hopeless. But we still whistled as we trudged the trail– if we were still on the trail. With the snowfall it was so hard to tell. What else could we do but whistle? It seemed such a simple and effective plan.

I turned my eyes on Brian and Chris. They looked as cold and frightened as I was. I couldn’t show it, though. I was the scout master. They trusted me.

“Tell you what, boys. The wind is too loud for the whistles. I think we should go back to the others now and move over to the visitor center. It will be warmer there.”

“But Doug and Shawn and Paul are out here somewhere,” Brian said, having almost to yell over the moaning of the wind through the trees.

As if I didn’t know that.

“I think it’s time we got some help,” I said. “Come on, boys; we need to turn back.”

I tried to sound calm. Not to let the hysteria show in my voice. Three boys. Doug Wilson and Shawn Peters... and Paul Singleton. They were real. They were all somebody’s son. And I was responsible for them.

Oh, God. Let me wake up. Let this be a dream. Three boys. All somebody’s son. Paul my own son.

Yes, Brian, I damn well do know how hard it is to turn back. But you are my responsibility too.

Only one car at the parking area.

“They’ve already gone over to the visitors’ center,” a grim-faced Al Jones, assistant scout master, said. “Travis thought we’d better call it in. You were gone too long.”

The visitor’s center was still deserted when we gathered over there. I’d left Al at the parking area– just in case the boys turned up there. Travis had used the emergency telephone on the center’s porch.

The wind wasn’t too bad at the visitor’s center. More than once I told myself to get back out onto the trail– that the wind had calmed down. But the whipping of the tops of the trees told me differently. We were just protected here. God, I thought, I hope the boys remember how to hunker down. What had we studied so far in survival training? So many years, so many boys. I couldn’t remember what we’d covered this year. Paul was a senior scout. I’d put him with Doug and Shawn on purpose– a steadying influence. Both of them sort of smartasses. Should I have set the groups up differently?

I heard the sirens from a long distance. If I could hear the sirens, why couldn’t we hear the whistles on the trail? Coming from both ends of the parkway. The world gone angry, whirling red.

Help had arrived. It should have lifted responsibility from my shoulders. But, of course, it didn’t. These were my boys. Paul was my own son. Lots of help. Too much help.

“We’re where three counties meet,” Travis responded to my look of confusion. “Three sheriffs’ departments. And the Park Service too.”

I went, frantically, from one to the other as they milled around, talking jurisdiction and organization, compartmentalizing the search grid, discovering their communications systems didn’t match. Talking, posturing, getting nowhere.

Another vehicle approaching. A van, with antennas on top. The media.

I reached for the cell phone. It was time to call the families. They shouldn’t first learn of this on the TV news. The hardest call was the last one.

“You’re late. We held dinner for you for a while, but Cindy was getting hungry, so we went ahead and ate.”

“There’s a problem, Margaret.”

At the end of a highly emotional exchange, Margaret said in that determined voice of hers, “I’ll find someone to sit with Cindy, and I’m coming up there.”

“Please don’t. Cindy shouldn’t be alone, and people will be calling to the house. There’s nothing you can do here. You can help best right where you are. They... they have it all under control.”

I almost couldn’t get that last sentence out. I didn’t want Margaret to know how much under control they didn’t have it. But who was I to judge or complain? They had come out on a cold, snowy night to find my son– the son I had lost.

But, at last, one of the sheriffs had asserted himself. I was panicked when I saw which one, though. An old Marine. No kids. The other two sheriffs had young sons. That meant a lot to me right now. I built up the courage to approach the sheriff after, at last, he’d organized and dispatched search parties.

“Don’t they have airplanes or helicopters for this sort of thing? We tell our boys to look for them in case of trouble. They know how to signal.”

“Can’t. Too windy. Not much to see at night anyway,” he answered– rather abruptly, I thought. But of course he was right.

He hadn’t even looked at me. He knew who to blame for this too.

At that moment, Shawn Peters' parents pulled up in their SUV. Ed Peters made a beeline for me, his wife, in curlers, dragging him down with a grip on his arm, yelling for him to calm down, she almost in hysterics herself. I braced for the onslaught. Ed Peters was quicker to find fault than to pitch in and help. And he had a lot of fault to find in me right at this moment.

I hadn’t gotten hold of Doug’s parents yet. He was supposed to spend the night with us after this scout outing. I assumed they were out partying, given the free night. God, I hoped whatever bar they were in didn’t have a TV.

* * *

“Hey, look. I can see a big pond down there in a fold between the hills.”

“Yeah, it looks frozen,” Shawn said. “I wonder how deep it is– and how thick the ice is.”

“Don’t know,” Paul answered. “But it’s about time for us to turn back. We must be almost out of the sector we were assigned, and we’ve only got three-quarters of an hour to get back to the rendezvous point.” Paul gave a long, lingering look toward the pond, though. He could remember going skating without skates on the pond on his granddad’s farm.

“Last one down gets cleanup duty at the next den meeting,” cried out Doug as he took off down slope through the trees.

The other two boys raced after him, laughing.

* * *

I’ll never forget the smell of varnished old pine. It will forever conjure up what the sheriff said when he thought I was asleep– or I certainly hope he thought I was asleep. I was curled up on the floor of the visitor’s center, exhausted and unable to sleep I was so keyed up. At the same time I had my eyes scrunched closed, trying to shut out reality and providing an excuse not to be here, the last place I wanted to be.

Ed Peters was perched on a straight chair over near the center’s book rack, the essence of a rumbling volcano, ready to erupt at the slightest excuse. His eyes were boring into me. His wife was ineffectually fluttering around, trying to be domestic with no means to do so or anyone interested in being thus served– but obviously trying to maintain a claw hold on her role in life.

I had sent Al and Travis down the mountain with the remaining scouts– the ones whose parents hadn’t already driven up here and snatched them away. They would make sure the boys got home, with explanations– sort of a hollow gesture of responsibility, I painfully knew. And afterward Travis would try to find Doug’s parents. I didn’t envy him that.

I knew we’d already been on the 11:00 news. By then, there were two film crews up here and both did live segments. They wanted me on film, but the sheriff in charge insisted that only he be interviewed– and that was fine with me. I never could understand how the relatives of the victimized or lost could speak on camera. I knew I wouldn’t do more than cry. And that certainly would bolster everyone’s confidence.

I must assume the sheriff thought I was asleep when he turned to a colleague of one of the other counties and said, sotto voce, out of Ed Peters’s hearing, “It’s almost 3:00 am. It’s getting too dangerous out there. It’s time to turn off the search for tonight and come back tomorrow to look for the bodies.”

I section my life into two segments– the years before I heard that statement, which was a period in my life that I only thought I endured problems and grief but that really were the innocent years, and all of the years after I heard the sheriff say that, when I knew how precious and fleeting life and happiness were. I felt a fist grip my heart and squeeze, and I could barely breathe. Even my moan was too strangled to be heard.

I was rent asunder. Emotionally, I knew that I should reach out in concern for the parents of Shawn and Doug, but in those moments I was so overwhelmed with the terror and grief of this sentence so casually and callously inflicted on my own son– all because of what I had failed to do– that I could think of no one but my own Paul. I even, I am mortified to think, resented Ed Peters at that moment. He had more time than I did. Maybe merely moments before he realized that the sheriff was shutting down the operation. But precious moments of innocence and hope that I no longer had.

I closed my eyes even tighter, willing them all to leave. All of them just to pack up and drive off, knowing that as soon as I was alone, I would bundle up once more and be out on that trail. I knew what that inevitably meant. And in my grief and frustration and deep sense of guilt, I embraced it.

* * *

“Be careful, Shawn. That section of ice looks too thin to hold you.”

“Didn’t even see it. It’s too dark,” Shawn answered.

All three boys looked up to the sky at the same time, as if just now, in consort, awakening from a deep sleep. It was dark and snow was beginning to fall. And it was cold and the wind was picking up.

“Shit, we’re late for the rendezvous,” Paul declared, having looked at his watch.

“Better get back on the trail pronto,” Doug said, working his way to the edge of the pond.

Once out of the pond, the three turned in separate directions.

“Which way to the trail?” Shawn asked.

“Should be to the west of us,” Paul said. “Whichever way the sun went down.”

“You see the sun go down? I didn’t see the sun go down.” It was Doug who said this, but it could have been any of the three of them.

“Uphill?” Shawn offered.

“Which uphill?” Paul snorted. “We’re in almost a hollow. It’s uphill on three sides.”

“The downhill side must be east then,” said Shawn, trying to keep logic going.

“Maybe,” Paul answered. “But you can’t tell in the Blue Ridge. Can we be sure which side of the ridge we’re on?”

“We can use the compass. That’s what we came out here to practice.”

Shawn and Paul turned and gave Doug a sharp look. It was the most intelligent thing he’d said this school year. But then no one spoke up to claim having the compass, and the three shared gazes of disgust and the beginnings of fear.

“Three hills. Three of us. We should each take a hill, and whoever finds the trail can give a shout.” This time Shawn’s less-than-brilliant idea.

“I’m already shouting and you can barely hear me four feet away,” Paul countered. “The wind. It really moans on the mountaintops. And, no... basic survival. What my dad taught us. We stay together and we stay in one place. Someone has to come for us if we’re getting out of here tonight. Tomorrow we can be more adventuresome.”

“I’m cold. And it’s snowing,” Shawn whined.

“Branches. You gather branches, Shawn. And, Doug, you look for a good sheltered spot. Down low, in a small ravine, away from the direction of the wind, if we can decide what’s prevailing. I’ll build a fire.”

“Not here,” Doug said. “Your dad warned us how easy a forest fire could start in a dry winter like this.”

Once more looks of surprise and just a bit more respect went Doug’s way from the other two. He’d remembered what they hadn’t.

“Then we’ll build it out on the pond. On the ice,” Paul answered, a sense of determination in his voice and surprising even himself that he had come up with this solution. They needed to stay calm. And they needed a leader. Paul knew this is why his dad had spent all this time in scouting with him– to make him a leader in trouble like this. “If anyone’s going to find us tonight, it will be because we gave them a signal location.”

“Won’t it just melt through the ice?” Shawn asked.

“Yes. And then we’ll build another one, if we have to. We’ll take turns. We each have our poncho. We’ll huddle together for warmth in whatever shelter we can put together. We’ll take turns being in the middle, and when the fire goes out, that’s the guy who’s got to go out and start another one. Food and water. My canteen’s pretty full. Yours?”

Both of the other boys wagged their heads to indicate that they had enough for now.

“And food?” Both Paul’s and Doug’s heads swiveled toward Shawn, the food-obsessed of the three of them.

“You know I’m loaded with candy bars,” he said. “You laughed at me down in the parking lot for what I was bringing.”

"OK, go, go, go. Let’s get under cover.”

* * * *

Margaret almost didn’t answer the telephone. She was exhausted by the number of calls she was getting from friends and relatives– and complete strangers. All wanted to do anything they could to help. Two calls before, with a tearing heart, she had turned down an offer of help from a retired forest ranger. Ralph went to their church, and he recalled to Margaret that her husband had paid a house call on a stormy night and had doctored and stayed with his daughter until her fever broke and probably had saved her life.

“You say the word, Margaret, and we’ll go up there. I’ve gotten in touch with a group of other retired forestry service rangers. We know that area like the back of our hands.”

“They have more than enough help, Ralph. Thanks. But thanks. And, yes, I’ll let Matt know you offered and are ready.”

The selfish part of her had wanted to answer, “Yes, put as many people out there looking for my precious son as will go.” But she knew this wasn’t a night for a seventy-five-year-old man to be on the mountain in the woods. She could not conscience the risk of trading one life for another. Even her son’s. But she felt so powerless– and useless.

And on the next call, her world shattered.

“They’re calling off the search for the night, honey. The Albemarle sheriff is driving me home now. They dragged me out. Wouldn’t let me stay up there.”

The last thing Margaret said to him before he clicked off was, “Matt, it’s not your fault.” She wouldn’t have said it if she didn’t believe it. Everything didn’t have to be someone’s fault. She knew that everything Matt had been doing for years was to prepare young men for something like this– to teach them how to survive it. No matter what, she knew she had to convince Matt that this wasn’t his fault.

She let the phone ring five times before answering it next. She had sunk to the floor beside the telephone from the body blow of Matt’s call. She didn’t know if she could take any more of this.

“Margaret?”

“Steve?” She recognized the voice instantly even though they hadn’t spoken in months. She couldn’t even remember now what the falling out with her brother had been about. But, as she remembered it, it was too serious and too much Steve’s fault, she believed, for her to make the first move.

“I got a call from the guys on duty over at the Nellysford fire house. They say they’ve seen the pinpoint of a fire on the mountain. To the north of Wintergreen.”

“A fire? On the mountain?” Margaret felt like a dope. She didn’t know what that meant. The mountain was on fire? She knew they were in a heavy risk period. Everyone on the slopes of the Blue Ridge knew that. And a call from the Nellysford fire house? How in the hell could Steve expect her to care about a forest fire at a time like this?

“I understand that’s the area those boys should be in,” Steve continued. “The guys say the light comes and goes– but they have it pinpointed. I’m on my way to the firehouse, and we’re going up there on a fire trail the guys know about.”

“They’ve called off the search for the night,” Margaret said dully. “The Sheriffs have ordered everyone off the mountain.” Everything about her felt like it was paralyzed, shutting down. She could barely get her words out. Her mouth felt like it was full of cotton.

“Fine for them. But I haven’t called any search off. It’s our county up there, and it’s a fire. And... and Paul’s my nephew and you’re my sister.”

* * *

The boys first saw the lights of the flashlights across the pond, downhill. They had just decided that someone had to go back out on the ice and make another fire, but, without saying it, each had pretty much given up on that idea. And it was so cold, even huddled together like that. It wasn’t so much of either an adventure or fun anymore as they had been pretending it was.

Doug saw the lights first, and Paul told him that he was just hallucinating. If help was going to come, it should come down from the Appalachian Trail, not up the mountainside. But then Shawn said he saw the lights too. So they groggily and painfully stood up from their huddled crouch and stumbled out of their improvised shelter. They each instinctively knew if they didn’t and if it was a search party, it easily could just pass them by.

It had been Doug who suggested that at least one of them had to be awake at all times. Paul didn’t remember having read that in any of his survival manuals and he’d given lip to Doug about it, but Doug had stood his ground.

“I didn’t read it in the manuals either. Your dad told us that,” Doug said indignantly.

Doug had always been the dopey and smartass one. Both Paul and Shawn had badgered him about that. They soon knew they wouldn’t be doing that again.

“Uncle Steve,” Paul said, with surprise and relief, as the rescue party emerged from the snowy fog.

“Anybody want a Snickers bar?” Shawn asked, attempting bravado with a wan smile but not able to control the tremulous tone of his voice.

Paul’s voice cut into the icy mist. “Is Dad OK?”

~

Perennial Virginia Writers Club short story and essay winner Gary Kessler is the author of On the Downtown Mall, a short story collection. His upcoming mystery novel, What the Spider Saw, parallels the 1904 McCue murder case.