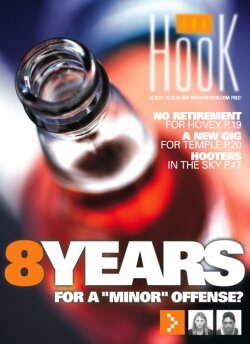

Eight years: for a 'minor' offense

All over Albemarle County there are women like Lisa Robinson. They volunteer at their children's elementary school. They haul the kids to extracurricular events. They yell at their teenagers to pick up their clothes.

One thing separates her peers from Lisa Robinson. They haven't been seen by TV cameras making a perp walk in shackles after being sentenced to eight years in jail.

Were it not for nearly a foot of precipitation that began falling over the weekend, the conviction of George and Lisa Robinson of 16 counts each of contributing to the delinquency of a minor might still be Charlottesville's top story.

The town buzzed about the August 16 birthday party they threw for Lisa's 16-year-old son and the details reported in the Daily Progress:

* the $360 worth of booze Lisa Robinson purchased for the party;

* the prosecution's portrayal of Lisa Robinson as a woman who lied to other parents about alcohol being served;

* and the saucy tidbit that once police showed up, Lisa allegedly advised the teens to gargle with vinegar to cover the smell of alcohol.

The Robinsons have been castigated in countless conversations as "stupid," even "terrible parents," with a sanctimonious community asking, "What were they thinking?"

And yet, this case highlights the complex role alcohol plays in our society at large and with teenagers in particular.

Just about everyone agrees that serving alcohol to minors is not a good idea (although there are some dissenters to that politically correct train of thought). And there's further debate about whether Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court Judge Dwight Johnson's eight-year-sentence to the Robinsons was well deserved— or a sign of a judiciary out of control.

Certainly the timing of the party– a month to the day after the alcohol-related death of 16-year-old Albemarle High School student Brittany Hope Bishop– didn't help the Robinsons' case.

Brittany Bishop "wasn't even cold in the ground," when they hosted the party, Judge Johnson admonished the couple. And after sentencing them to six months in jail for each of the 16 counts— to be served consecutively— he set bail for each of the long-time Albemarle County residents at $80,000, calling them "a danger to the community."

"You could have heard a pin drop in that courtroom," says Sally Howe, who was in court on February 10 when the couple was sentenced to eight years in jail. "I thought everybody was going to faint and have a heart attack."

The Outrage

"I think they should throw the book at them," says a parent of two Covenant School teens.

"They deserved it," says a Farmington Country Club member and father.

"There's no excuse for giving alcohol to teens except at a religious ceremony," says the mother of a Western Albemarle freshman.

But the outrage isn't all in one direction.

"You mean we're locking them up, and no one got killed?" asks Albemarle High parent Toby Gonias. She has another concern about the sentences given to the Robinsons. "Clearly they're liable, but I'm not sure locking them up for eight years is good for their children," she says.

Lisa Kenty Robinson is the mother of two boys, aged 16 and 12, with her first husband, Marc Kenty, who was also charged in this case with three counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor.

Fran Lawrence, Lisa Robinson's attorney, says he cannot recall any precedent for giving an active jail sentence for "permitting young people to drink alcoholic beverages."

He says that the Robinsons' sentence is in excess of that called for in Virginia for a fourth offense of driving under the influence, or for robbery– or manslaughter.

And it far exceeds the punishment handed the two teenagers convicted of providing alcohol at the July 16 party Brittany Bishop attended. A 19-year-old man received 30 days, while another minor got 10 days in jail.

A local attorney describes Judge Dwight Johnson as a conservative Christian with strong views, and says that Johnson seemed "unconstrained by precedent" in this case.

This attorney, who spoke on the condition of confidentiality, says, "The evil from the lawyers' point of view is that no weight was given to precedent." If you want to get tough on serving alcohol to minors, "you do it in increments," he adds.

Charlottesville Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) president Jill Ingram was surprised by the jail sentence— pleasantly surprised. "I'm not necessarily opposed to a judge trying to send a message that parents shouldn't supply other people's kids with alcohol. I applaud what [Judge Johnson] is trying to do."

Yet even MADD's Ingram notes that the Robinsons' eight-year sentences are "more time than other people get for drunk driving," and concedes they might not hold up under appeal.

***

Going into court February 10, defense attorneys for Lisa and George Robinson threw themselves on the mercy of the court. They knew the prosecution was going to recommend 90-day jail sentences. So both Lawrence and Jonathan Wren, George Robinson's attorney, believed that something less than 90 days would be appropriate. "In that court, a 30-day jail sentence would be harsh," says Lawrence.

The Code of Virginia allows a judge to penalize contributing to the delinquency of a minor with up to 12 months in jail and/or a $2500 fine.

"Historically, it didn't matter whether one was charged with 16 warrants or one," says Lawrence. That's because no one had ever been sentenced to 12 months in jail on one count. "It was unimaginable that the punishment for an adult giving alcohol to a minor, whether one count or 10, could put someone in jail for 12 months."

Public Defender Jim Hingeley denounces the eight-year sentence because it so profoundly exceeds the prosecution's request. "When you have a discrepancy of this magnitude, that's a sign that something's drastically wrong," he says.

Hingeley also considers the $80,000 bond an unreasonable ploy to put the couple in jail. Hingeley says a bond should not be used to punish, but merely to ensure that the accused don't flee or disobey the terms of their bond, and he questions whether the long-time Albemarle residents were— despite Judge Johnson's remarks— dangerous or likely either to flee or throw another beer bash for teens.

Hingeley points out that verdicts in Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court carry an automatic right of appeal that was effectively denied the Robinsons when Johnson set such a high bond. "It was," says Hingeley, "an arbitrary decision by the judge who wanted to stick them in jail."

As the shackled couple was led out of the courtroom, one observer described them as looking "like they'd murdered a child."

Are full-body shackles common for those facing misdemeanor charges?

"We do everyone that way," says Sheriff Ed Robb. Even someone convicted of a misdemeanor? "It doesn't matter," says Robb. "We don't discriminate."

"It's ridiculous," says Sally Howe, a neighbor of the Robinsons, who calls the treatment "embarrassing" and "humiliating." And there's been some speculation that the Robinsons' perp walk in front of waiting TV cameras was orchestrated to further drive home the consequences to any parents contemplating serving alcohol to teens.

After the couple spent a night in jail, their $80,000 bond was reduced to $5,000 each in Albemarle Circuit Court and they were released. An appeal hearing was set for April 7.

Discrepancies

The scenario laid out by the prosecution was fairly damning for the couple, who had already pleaded guilty to the 16 counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor. And because the defense strategy was to "hang our heads and say we're sorry," according to Sally Howe– who was there as a character witness for Lisa Robinson– the judge heard only the prosecution's versions of events.

"This is a situation of misguided parenting," admitted Lawrence afterward. "I am not sure we want to jail parents for a mistake in judgment."

But after such disastrous consequences for the Robinsons, their attorneys and supporters are now challenging the prosecution's version of events— although both Lawrence and Wren declined a Hook request for permission to speak to their clients.

According to Lawrence, the Robinsons believed that the kids would drink, and after the tragedy of Brittany Bishop, they felt it safer to have a supervised party, with any youths who drank spending the night.

What about the prosecution's assertion at the trial that Lisa Robinson lied to other parents who asked whether alcohol would be served?

"We believe that to be untrue," Lawrence says. "In the conversations we're aware of with other parents, they were told the kids would not leave. There was no specific mention of alcohol."

Sally Howe has known Lisa Robinson for eight years and now lives beside her on Bleak House Road in Earlysville. "Lisa was doing her best to stop a Brittany Hope Bishop situation from happening," Howe says. "She knew they'd drink if she didn't have the party. She told me that [her son] threatened to."

Albemarle Police Sergeant Scott Cox was the first officer to arrive at the party. After parents had been called to come pick up the 20 kids who were detained, he says, "I had parents who wanted to confront the Robinsons at the scene because they had been told there would be no alcohol."

Even though Howe was angry with Lisa Robinson for throwing the party, she doesn't believe Robinson is a fabricator. In her opinion, "These parents have a vested interest to lie and say they were told no alcohol would be present because they could be prosecuted for letting their kids go."

The defense also denies that 60 to 80 kids attended the party. "The number of people in attendance has been significantly exaggerated," says Lawrence.

"Lisa told me 30 were invited," says Howe, who was out of town the night of the party. She had two reports from people driving by that night that the only cars lined up on the road were those belonging to the police. And from Bleak House Road looking at the Robinsons' house, "You can't see anything," she adds.

Sgt. Cox estimates that around 50 kids were at the party, and he says 10 to 12 cars were parked on road, blocking one lane.

What about the claim that gargling vinegar can mask alcohol breath? That salacious allegation at trial came as a surprise to many area adults. (One asks, "How did we miss that when we were young?")

Camblos, however, classifies the suggestion in the same category as "putting a penny under your tongue"– an old wives' tale.

"Nobody is asserting any kid did that," says Lawrence. "We believe that didn't happen, and if something was said, it was said tongue in cheek."

"I don't believe that for minute," says Howe. "I think those kids made that up."

The bust

Sgt. Cox says he arrived at the scene at 11pm. "I saw kids in the backyard holding containers that appeared to be alcoholic beverages. They dropped them and ran." Mayhem ensued as teens fled into the woods.

"I was trying to find the kid who lived there because I assumed the parents weren't there," recalls Cox. "I was shocked that they were there. At first they acted like they didn't know any alcohol was there."

Ten minors were charged with having alcohol, says Camblos, explaining that the number charged does not have to correlate with the number of counts with which the Robinsons were charged. "You can be guilty if it's available at the house," he says. "It's a question of whether you're condoning it or have it available to minors."

Initially, the Robinsons were charged with 19 counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, until it was discovered that three of those "minors" were actually 18.

Lisa Robinson's ex-husband, Marc Kenty, although not present for the party, was charged with three counts. According to trial testimony, Kenty had iced down and delivered the beer that Lisa Robinson had purchased.

A source familiar with the case who declined to be identified says that when Lisa Robinson came to Kenty, the party was "a done deal." The 16-year-old's father said, "Keep it under control, and don't let them leave," says this source.

The first Kenty knew that anything had gone awry was when the police called him to say they had his son. When Kenty went to pick him up, he admitted to police that he'd delivered the beer. "He's been honest," according to this source.

Of the 10 teens who tested positive for alcohol consumption, says Lawrence, "They all had low blood alcohol counts. All were at .03 or less except for one. Two were at .03, and the rest were under that."

Virginia law forbids anyone with a blood alcohol concentration at 0.08 percent or higher from driving. Lawrence adds that there were ample food and soft drinks at the party, and "No one asked anyone to drink."

One of those arrested that night is a 17-year-old Albemarle High student. She says there weren't that many people there when she arrived at 9:45pm, but by the time the police came, she estimates the count had risen to between 60 and 80. This partier says the Robinsons were indeed taking away everyone's car keys.

She describes ice-filled trashcans full of "designer drinks" like Bacardi Silver and Mike's Hard Lemonade. "I didn't know I had anything to drink," she says, because she didn't realize the Bacardi Silver malt beverage contained alcohol.

When the police arrived, she recounts, "Everyone was pushing me to run, so I did." The girl eventually walked out of the woods— and was given a Breathalyzer that registered just .016. "Most of the people who were drinking heavily ran and got away," she notes.

Anne Skrutskie lives two doors down from the Robinsons. She never heard any noise from the party, but around 11pm she started hearing strange noises in her backyard.

"The first indication we had that something was going on was when I saw police running through our yard with flashlights," says Skrutskie. One of the officers knocked on her door so she wouldn't be alarmed. "He told us 100 kids were at a party," she recalls. "We were shocked there were that many."

Skrutskie wonders how the police knew about the party in the first place and whether cars were blocking the road and a passing motorist had called. "We certainly were not the ones who called," she says.

Eighteen-year-old Lindsay Howe was driving home that night about 12:15am, and the only cars she saw on Bleak House Road were police cars in front of her house next door to the Robinsons. She thought her house was being robbed, reports her mother, Sally Howe.

"There were kids running through our yard and hiding in a tent in our backyard," Sally Howe says. "We found shoes and flip-flops for days in our yard."

Another teen who had planned to attend the party drove down Bleak House Road around 10pm— although she doesn't remember the time for sure. She says she saw no cars lining Bleak House Road, the usual tell-tale sign of a party— except for the police cars, and she didn't stop. So how did police know a party with underage drinking was going on?

"They received calls from parents whose kids were not going to the party indicating that alcohol might be served," says Jonathan Wren, George Robinson's defense attorney, in an interview. He said that information came out at a hearing to suppress evidence as a result of an allegedly unconstitutional search.

But Sally Howe has another theory.

Character witness

The Robinsons have lived next door to Sally Howe since December 1999, but she's known 38-year-old Lisa Robinson since their 12-year-old sons were in preschool, when Robinson was still married to Marc Kenty.

Howe, a 47-year-old nurse whose husband is on the faculty at UVA, describes Lisa Robinson as "very community oriented." When Howe started a foreign language program at Broadus Wood Elementary School, Robinson "bent over backward" to substitute for the program. Robinson served on the PTO there and coached soccer with Marc Kenty for years, says Howe.

"I was very impressed with her from the start," says Howe. "She says what she thinks, and you know where you stand with her... I can think of countless times she's gone above and beyond the call of duty. She always given her all— and not just money."

Sally Howe was in court February 10 as a character witness for Robinson, but she was not called to testify. However, she makes one thing clear: While she has known Robinson for years and lives next door, "She's more of an acquaintance than a friend," says Howe. "We exchanged child care, but we've never done anything socially."

She wants it understood that she's not defending Lisa Robinson because they're friends. "What happened [to her] was uncalled for and unreasonable," says Howe.

Howe and others describe George Robinson, 48, as someone who enjoys expensive vehicles. Anne Skrutskie says she met George Robinson only once, but knew he drove a Hummer, the four-wheel-drive military vehicle that can retail for over $100,000.

Sitting on a four-acre lot, the Robinson home includes an in-ground swimming pool and is assessed by the county at $439,000.

Howe says that trouble in the Robinsons' marriage intensified after the party, and George Robinson moved out three weeks after the arrests. His attorney, Jonathan Wren, confirms that the couple are separated.

After the party, Howe was angry, and she says she asked Robinson straight up: "What the hell happened?"

"She said, 'I made a terrible mistake,'" Howe reports.

Howe was not surprised that Lisa would spend $360 for alcohol. "They're so stinking rich, that's nothing to them," she says.

In court, prosecuting attorney Jim Camblos noted the audacity of Lisa shopping for the beer at Kroger with her 16-year-old son and another kid, relates Howe. Police found out about the purchase from Sergeant Cox's investigation. "The manager remembered her," says Cox.

The kids invited to the party are athletes and had arrived home around 9 or 9:30pm. Lisa's job was to supervise the girls while they showered and to make sure they weren't having sex with the boys upstairs, according to Howe.

All the booze was supposed to be in the rec room, Howe adds.

While Lisa Robinson was upstairs keeping an eye on things, she told Howe, George Robinson moved the bottles outside— while admonishing kids not to break any bottles around the pool.

"The prosecution didn't care that only one kid left," says Lawrence. "He wasn't drinking, and he left after the express permission of his parents."

Lisa Robinson told Howe something else: That she believes the call to the police came from the Robinson home.

Police say the call went directly to Albemarle County Police— not to the 911 center— and that there's no way of telling who made the call.

"It was from one of the parents who said they believed there would be underage drinking," says Cox. Did the call come from the Robinson house? "I haven't heard that," replies Cox.

Howe is troubled by something else. She called Sgt. Cox, and she claims he told her, "We're going to throw the book at [Lisa Robinson] because she bought the booze, and we're going to make an example of her."

"I told her it's likely the judge would throw the book at her— but I don't make that decision," says Sergeant Cox.

What's a mother to do?

Sally Howe admits that in her youth she attended plenty of parties where there was underage drinking with adults present. Another Albemarle High parent who does not want her name used says, "When I was in high school, this was done all the time."

Times and attitudes about alcohol have changed, and now the same people who boozed it up as teens find themselves renouncing such acts as parents.

But despite DARE programs, "zero-tolerance," and the many warnings which inundate children, teenage drinking continues unabated, often under the eyes of parents who believe, like Lisa Robinson, that if their children are going to drink, it's safer for them to do it at home than out driving around.

"There's quite a few parents who do that kind of thing," says the 17-year-old Albemarle High student who was charged at the Robinsons' party.

If the Robinsons thought that drinking under supervision was okay, they're not alone.

* In 1998, nine parents at the tony Collegiate Schools in Richmond's far West End were busted along with 66 graduating seniors after buying five kegs to keep the party-goers safe, according to voluminous press reports. The party occurred at Tuckahoe, childhood home of Thomas Jefferson, and many of the busted parents were Richmond notables.

*At a private graduation party last year for St. Anne's-Belfield seniors, alcohol was served both to the parents and to underage grads who were there, reports a source who declines to be identified.

* Over the holidays, another source tells of a party where a parent allowed her underage daughter, a college student, and six friends to stay home and drink.

"We're all guilty," says Howe. "I don't know one parent who's never served their kid a glass of wine." Howe is thankful her children don't like alcohol, and says her 18-year-old daughter usually finds herself the designated driver at social events.

As far serving alcohol to other people's kids like the Robinsons did, Howe says, "Do I approve of what they did? Hell, no." At the same time, she doesn't like what's happened to Lisa Robinson.

"I don't think it's fair for St. Anne's parents to get a slap on the wrist," says Howe, referring to the 1997 case of an Ivy couple ordered to perform 100 hours of community service because guests brought alcohol to their daughter's party. "This goes on all the time," says Howe.

She recently hosted a party for her 15-year-old. How many people called to ask if alcohol would be served?

"Three out of 35," she answers. "It's crap about parents calling. They do not call." And of the three who called, only one asked whether alcohol would be served— and told Howe she felt ridiculous posing the question. Howe says she volunteered the information that there would be no alcohol to the other two parents who called.

Do Europeans have a better attitude toward alcohol? One Albemarle High parent, who grew up in Europe, says she was always served watered down wine at Sunday dinner. Another county parent who spent her teen years in Germany recounts that going to pubs to have a beer was an accepted activity, and that she never saw adolescents drunk— until she returned to the United States.

During the Reagan administration, all American states– under threat of losing federal interstate highway money– raised their various drinking ages to 21. Just as with sex and drugs, this country has advocated abstinence as the only proper course for minors. Has zero tolerance worked?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a study in December 2002 that showed binge drinking shot up 17 percent among 18- to 20-year-olds between 1993 and 2001. However, a University of Michigan study showed a slight decline in binge drinking among 10th graders in 2002, from 24.9 to 22.4 percent.

According to the Michigan study, incidences of five drinks or more being consumed in a row have dropped from 41.2 to 28.6 percent in the past 22 years. And since 1980, when 72 percent of all high school seniors reported using alcohol, that number has dropped to 48.6 percent.

Even more importantly, the National Commission on Drunk Driving says that between 1982 and 2001, the number of car crashes in all age groups has dropped 46 percent.

The 17-year-old who spoke with The Hook says that since her arrest, "I'm definitely trying to stay away from any situations that might be dangerous. It's not worth the trouble."

This teen also notes that European teenagers seem to drink more responsibly and are not doing it "rebelliously."

Prohibition made alcohol illegal from 1920 to 1933, until the U.S. government conceded that the Volstead Act had not slaked people's thirst for booze. Nor has the war on drugs stifled the demand for drugs– although it has incarcerated a generation of Americans who are disproportionately black.

While education and changed attitudes appear to have had some effect, the fact remains that teenagers continue to drink, use drugs, and get pregnant.

But safety is not the only issue. Parents worry that if their children are caught drinking, their college careers could be ruined. Parents ask their kids if alcohol will be served at a party, and if the teen says no, they feel they've done all they can. They tell their children to call them if they have been drinking and need a ride home. "What are we supposed to do?" asks Howe. "It's that confusing for parents."

Judge Johnson's eight-year-sentence is certainly something else to consider for any parent who thinks it's safer for teens to drink at home. Even Brittany Bishop's parents were surprised by the severity of the sentence. "I think they want to drive the point home," says Kellie Bishop.

Brittany's legacy

On July 16, three Albemarle High School girls attended a couple of parties where alcohol was served, with tragic results. Around 2am, the Honda Civic driven by 17-year-old Kirsten Zamorski flipped over on Earlysville Road near the reservoir. Sixteen-year-old Brittany Bishop, a passenger in the car, died at the scene, and Zamorski spent weeks in the hospital. Police cite drinking as a factor in the accident.

Besides the unfortunate timing of the Robinsons' party a month after Brittany's death, the prosecution brought up another connection: a romantic link between Brittany and Lisa Robinson's son.

Kellie Bishop met Lisa Robinson when their children were dating– "as much as you can call it dating with kids who don't drive," she says.

"I was surprised— shocked— they'd had that party," says Bishop, because the first time Robinson's son came over to her house, Lisa Robinson called to see if it was okay, if Bishop would be there, and what time to pick him up. "I was impressed that she did what any responsible parent would do," says Bishop.

Still grieving over their daughter's death and determined to prevent the same from happening to others, Kellie and Beau Bishop set up a drive-home service for teens called BRITT: Beat Risking It—Take a Taxi. The program is available to anyone who's been drinking or doesn't feel safe driving, no questions asked, by calling Yellow Cab and mentioning BRITT.

Kellie Bishop adds to the debate on teenage alcohol use the perspective of someone who's been there: "It's bittersweet having my daughter's name mentioned," says Bishop, her voice breaking. "It's hard to have her be the example."