Halloween mystery: 99 years later, the McCue murder

The 1904 murder of the wife of ex-mayor J. Samuel McCue is more than a Halloween mystery. For 99 years, the killing and its sensational trial have become the stuff of legend. Last weekend, the annual "Spirit Walk" re-created part of the trial, and three years ago a local collector paid $70for the rope that hanged the man who supposedly did the deed. But reporter Paul Jones has studied the case of Charlottesville's most celebrated murder and thinks an injustice was done. While jurors and contemporary news accounts rapidly convicted McCue, Jones went back to the facts– still preserved in the Charlottesville Circuit Court– to uncover an alternate history.–editor

Charlottesville was an angry town in September 1904. The former mayor's wife had been murdered, and the citizens wanted justice. They got their wish. The alleged killer– her husband– was tried, convicted, and hanged.

In the nearly one hundred years that have passed since the murder of Fannie McCue, no one has stepped forward to publicly defend her executed husband, J. Samuel McCue. Even most McCue descendants seem to prefer to let the matter rest, to let the story remain buried. Indeed, to suggest that Sam McCue had not murdered his wife would be to suggest that Charlottesville had put to death a prominent city figure– unjustly.

***

On the icy early morning of February 10, 1905, 12-year-old Vinton H. Valentine climbed to the attic of his home at 303 High Street and watched as Sam McCue slipped and almost fell on the ice on his way to the scaffold. Valentine could see McCue speak to his jailers but could not hear his remarks. As McCue was led up the steps of the gallows and positioned over the trap door, young Valentine saw the executioner place the noose over the prisoner's head and cinch the rope down tight– but unfortunately not tight enough.

Placing the hangman's knot at the back of Sam's head would insure that his neck would break in the fall. At 7:34am, J. Samuel McCue, former Mayor of Charlottesville and father of four, disappeared from sight. Young Vinton Valentine did not see McCue struggle and kick for 19 minutes before he strangled to death. The hangman had done a poor job of placing the knot.

The crime

At about 6pm on September 4, 1904, after arriving from Washington, D.C., by train, Sam McCue entered his Park Street home and went immediately upstairs to bathe and change clothes. His wife, Fannie, having arrived home around 5pm from visiting Sam's cousin, Mrs. R.D. Anderson, in Red Hill, was in the parlor with a neighbor. Three of Sam and Fannie's four children were visiting relatives. Only the oldest, 16-year-old J. William "Willie" McCue was at home.

According to Willie, dinner that evening was cordial and uneventful except that both his parents reprimanded him for lending out Fannie's phaeton (horse carriage) for a trip to Keswick.

Sam and Fannie left the house to attend the 7:45pm services at First Presbyterian Church, then located on East Market Street (and now the site of a parking lot behind Wachovia Bank).

At the front gate of their house, Sam announced that he had to return to "answer the call of nature." By the time Sam reached the street again, Fannie was gone. She was seated in their pew when he finally entered the church. This failure to be seen arriving with his wife permanently colored analysis of that evening. Furthermore, as described later, Fannie's out-of-town junket may have set the sinister deed in motion.

***

Leaving the church about nine o'clock, Sam and Fannie walked up Second Street to High Street and then down Park Street. Their house, two blocks north of High at 601 Park Street, still stands as Comyn Hall, a retirement home.

At their gate, the couple stopped to talk with Sam's uncle, Marshall Dinwiddie, who later testified that both Sam and Fannie invited him in "very cordially." But he insisted that he had to get home and left them at the gate.

Mr. and Mrs. Frank Massie, sitting on their porch across the street from the McCue residence, heard the conversation and saw the McCues enter their house and dim the lights. "How soon they retire," remarked Mrs. Massie to her husband. The time was 9:15pm.

Ten to 15 minutes later, Frank Massie saw Dr. Frank McCue, Sam's brother, rush into the house. (Mr. Massie saw something else that night, but because of a speech impediment he could not speak well enough to be understood by anyone other than his wife. He wrote down what he had seen, just a few brief sentences, but even he did not appreciate its importance.)

What transpired in the 10 to 15 minutes between their entering the house and Sam's frantic phone call pleading with the operator to "Get someone, anyone!" has always been a mystery.

The prosecution would claim that Sam got into a violent argument with his wife and then bludgeoned, strangled, and shot her. They would tell the jury that Sam had killed his wife in cold blood, despite knowing that Willie– who had gone out that evening to make a social call– could walk in at any minute, and despite knowing that he had no alibi and that neighbors and family had observed him entering the house with Fannie just minutes earlier. Had Sam wanted to get arrested for murder, he could not have devised a more blatant way to go about it.

A 1989 article in Albemarle magazine summarized the conventional wisdom: So arrogant was McCue that he thought he could get away with murder.

***

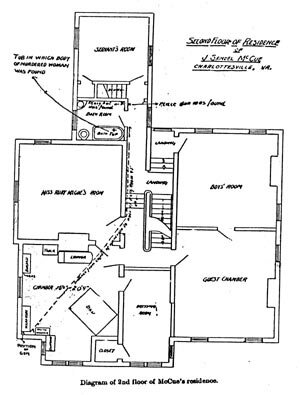

McCue presented his story at a Coroner's Inquest held the Tuesday after the murder. He claimed he was attacked and knocked unconscious after he noticed someone enter his bedroom from the adjoining (daughter Ruby's) room. As he reached for the shotgun that he kept in the corner next to the chiffonier, he was struck on the right side of the face.

After a moment of unconsciousness, he came to and staggered into the hallway in the near darkness. He saw and smelled gunsmoke. Descending the stairs to the first floor, he grabbed the telephone and asked the operator for his friend, Mr. T. J. Williams on High Street. Upon being told that the line was busy, he begged the operator to "Get someone, anyone– I have been attacked by an intruder, and Fannie may have been shot!"

Sam did get through to his brother, Dr. Frank McCue, who lived two blocks south at the corner of Park and High Streets. Grabbing his black bag and searching unsuccessfully for his pistol before leaving on foot, Frank arrived just before 9:30pm. Entering the front door, he found Sam sitting, dazed, about half way up the stairs.

Frank climbed the stairs toward him, and Sam pushed him on the back saying, "Go find Fannie." As Frank proceeded up the stairs, he heard water running in the bathroom. He entered and lit the gas lamp on the wall, to discover Fannie lying in the tub, hot water up to her breast.

Finding no pulse, Frank turned off the water and returned to Sam. He met Policeman Grady (who had been summoned by the telephone operator) at the top of the steps and led him to the body. Sam approached from the hallway and learned that Fannie was dead.

As Sam knelt and sobbed, Grady began his search of the house. Grady had already ordered a cordon of men to surround the premises so that no one could make an escape. He may have been only minutes too late.

The inquest

By the next morning, Monday, September 5, everyone in Charlottesville knew that the former Mayor's wife had been murdered. The populace was irate. That morning Sam McCue took out an ad in the Daily Progress offering $1,000 reward for information leading to the conviction of the killer. He also did a very curious thing for a "guilty" man. He hired the Baldwin Detective Agency of Roanoke to come and investigate the crime. The City of Charlottesville agreed to split the cost with Sam as the local police department had no "detectives."

An even more curious event took place the next day, after the Coroner's Inquest. The Baldwin Agency, although originally hired by Sam, informed him that henceforth they were working for the City and not for him. After less than one day on the job, they were convinced that Sam was guilty. (Generously enough, Mr. Baldwin did not charge Sam for his work. The City of Charlottesville was not as generous. Sam's four children were later billed for the trial and execution of their father.)

A suspect, Lester Marshall of Earlysville, was implicated but quickly cleared. Marshall had motive enough: He had come before Sam and Sam's brother, E.O. McCue, in various legal proceedings, and his estranged wife was probably having an affair with Sam. But he also had an airtight alibi.

***

The coroner's jury met on Tuesday, the day of Fannie's funeral. Reporters were streaming into Charlottesville from Richmond, Washington, and Baltimore. There was a fever in the air. The inquest became an inquisition.

It is fair to assume that Sam had enemies. He was a successful attorney whose specialty was debt collection, and he was good at his job. As the only man ever elected Mayor of Charlottesville for three terms (until Frank Buck in 1984), he had political enemies as well.

Not one word of testimony at the inquest indicated that Sam had killed his wife, or that he himself was not injured in the attack. Neither the police nor the detective agency could turn up any physical evidence that Sam McCue had committed murder. Likewise, there was testimony that suggested an outside aggressor.

The testimony of John Perry, the houseboy who lived in the back of the McCue house:

Q. You heard her [Fannie] halloing and crying?

A. Yes, she was hollering, "Oh, Sam, he has killed me; I am dying, I am going to die." And then after I knew that it was not Mr. McCue in the hall [italics added], I heard the man going down the front steps.

Q. You heard her calling like she wanted Mr. McCue?

A. Yes, sir. I never did hear Mr. McCue's voice at all.

Dr. Frank McCue, on Sam's injuries: "I observed a good deal of swelling, discoloration and the skin broken, and some blood running from it. I observed that as I was in the light. I myself personally saw blood issuing from his nose– that is one of the symptoms we look for in an injury to the head."

Despite this testimony in his favor, the jury needed to accuse someone, the citizens wanted someone to try, and the newspapers existed for something sensational to write about. Sam McCue was indicted for murder in the first degree. There were no other official suspects.

The trial

All the prosecution had was circumstantial evidence, and they used what they had very skillfully. No one was allowed to sit on the jury who was opposed to the death penalty or who said that they could not convict solely on circumstantial evidence.

The defense team, led by local attorney G. B. Sinclair, had several major obstacles to overcome, mainly public opinion and the press. The defense could not explain Fannie's death, nor could they find another suspect. They were forced to try to prove a negative: that Sam had not committed the crime.

The physical evidence that the prosecution hoped would hang Sam McCue consisted of Sam's shotgun, Fannie's bloody nightgown, a baseball bat belonging to the McCue boys, and Sam's undershirt, which appeared to have a small amount of blood on it.

The only physical evidence available to the defense was some letters between Sam and Fannie purporting to show what a loving relationship they had. Testimony would decide Sam McCue's fate.

The poor and middle class of Charlottesville had little sympathy for a well-off attorney accused of a heinous crime, and the upper class had less. Just as public opinion had been running against Sam McCue since the inquest, so was the testimony of some of the witnesses. Memories were conforming to the collective wishes of the community. It didn't help that both jurors and witnesses were permitted to read the newspapers of the day.

Inconsistencies abounded:

* Sam's wounds. Dr. J.E. Early testified at the inquest that Sam had a "contusion" on his cheek when he examined him the day after the murder. Four weeks later, at the trial, Dr. Early described it as only a "lump." On cross-examination Dr. Early could not satisfactorily explain the discrepancy except to say that a "lump" was not a sign that Sam had been struck hard enough to have been rendered unconscious.

* The bloody t-shirt. At the inquest, the undertaker, a Mr. Brierly, swore that when he was handed Sam's undershirt, his hands were bloody as he was still working on Fannie's body. Four weeks later, at the trial, Brierly testified under oath that he had finished preparing Fannie's body and "had washed his hands" before he was handed Sam's shirt. The defense team hammered at his contradictory testimonies, yet he held firm that what he was saying now was the truth.

* The philandering husband. Fannie McCue's brother, Ernest Crawford, who had lived with the McCues while attending the University of Virginia, said in the trial that Sam and Fannie "had the most unhappy household that I ever saw. We all anticipated this trouble," he added. "Mrs. McCue not only appealed to us, but appealed to Mr. McCue's brothers, telling them of the adulterous life their brother was living." Even if the jury ignored rebuttal testimony– from the McCue brothers and Fannie's father (who had chosen Sam as administrator of his will)– Crawford had asserted only that Sam was an adulterous husband, not an abusive or murderous one.

* The undamaged entrances. The prosecution tried to show that there was no break-in the night of the murder, thereby "proving" that the deed had been an inside job. However, Officer Dan Grady's testimony showed that there was no need for one– he found three windows wide open, two on the first floor. Furthermore, teenaged Willie McCue testified that he had left the front door unlocked that night.

* The time problem. The prosecution tried to establish that Sam had killed Fannie in a fit of violent rage after a bitter argument. When did this argument take place? Testimony proved that the McCues bid goodnight to Mr. Dinwiddie at approximately 9:10pm.

Officer Grady said that he arrived at the McCue residence by 9:30– after Frank McCue! An engineer for the city, C. L. DeMott, testified that with Fannie's 115 pounds in the bathtub, it would have taken 16 minutes and 40 seconds to fill the tub with hot water. When Dr. McCue arrived at the house after walking two blocks and discovered the body, he turned off the tap and the water was up to her breast. Fannie must have started her bath almost immediately after going upstairs. Then, instead of getting into a violent argument, she took the time to change from her church attire into her nightgown. There was no time for an argument.

Comyn Hall's the site of a bewitching tale

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Reasonable doubt: an alternate scenario

The fact that Sam ever became a suspect resulted from an accumulation of small facts and theories that, standing alone, did not amount to much, but which taken together proved insurmountable to a jury that was already tainted with public opinion and published gossip.

But there was reasonable doubt– and enough of it to allow creation of an entirely new scenario:

The murderer of Fannie McCue could have been Hattie Marshall, the 22-year-old wife of the police's initial suspect. The young couple had been tenants of Sam's for over a year. A month before the murder, she had moved, alone, to Court Square, two blocks from Sam and Fannie's house, and had hired Sam to represent her in divorce proceedings. She and Sam had carried on an affair for over a year, and it's possible that she had given birth to his child, according to a book by two Daily Progress reporters (A History of the McCue Case, by E.R. Chesterman and Joe F. Geisinger) that appeared shortly after the trial.

While Sam was in jail awaiting execution, he received a letter from his former lover which said, "I have the little picture of you, and it is all the comfort I can get to look at it and something else you understand that is so much like you!" The letter was signed simply "H." Sam knew who it was.

Hattie knew that Sam was returning from Washington on Sunday, September 4, 1904; indeed, she may have made the trip with him. She also knew that Fannie was in Red Hill that weekend. If she saw Sam walking to church alone that night (Sam had to pass Court Square), she may have assumed that he was going to be home alone afterwards. She could surprise him by being there when he arrived home. Waiting until dark, she could have left her apartment and walked North, turning up the dirt lane behind Sam's house so as not to be seen entering his house from Park Street.

When Sam and Fannie entered the house together just after 9 that night, Hattie may have been waiting upstairs. Upon hearing Fannie's voice, Hattie could have left Sam's bedroom and hid in Ruby's room which connected with it. Hoping to leave surreptitiously, she had to wait for the proper moment. While waiting, she could overhear any conversation going on in Sam and Fannie's bedroom. An intimate conversation between man and wife may have triggered hate and jealousy and turned this Sunday evening into one of blood and death.

As Fannie walked down the hall in her gown and started to draw her bath, Hattie could have grabbed a poker from next to the fireplace in Ruby's room and attacked Fannie from behind. One overhand swing from the assailant left a dent above the door that can be seen to this day. The next strike nearly severed Fannie's ear and knocked her to the floor.

Over the noise of the bath water, Sam, standing 42 feet away in his room, finally heard the screams that John Perry later misinterpreted as being, "Sam, Sam, he's killing me!"

Sam kept a Winchester 12-gauge shotgun in a cloth case in the corner next to his chiffonier. As he removed it from the case, Hattie could have stepped into his room and struck Sam on the side of the head as he turned to face her. Sam could have seen and recognized his assailant as he sank to the floor. Hearing Fannie still screaming down the hall, the assailant picked up Sam's shotgun and returned to the bathroom.

Fannie had gotten to her knees and was attempting to stand when the shot hit her over the breast, cutting her aorta, breaking three ribs, and finally coming to rest near her spine. She was dead when she hit the bathwater.

John Perry testified that Fannie's screams woke him up. He then heard her run into the bathroom. He "heard a man go in the bathroom twice and then go down the steps. He had on heavy shoes." Yet John Perry swore that he never heard a man's voice.

Charles Skinner lived next door and served as a coachman to a neighboring family, the Morans. He heard a woman's screams and then a gun blast. In his sworn testimony, he stated that he got to his window about 30 seconds after the blast but saw no one. He, too, swore that he never heard a man's voice.

What Skinner and Perry may have heard was the voices of two women. That they could not differentiate between the two is understandable: They thought that the only woman in the McCue house was Fannie. The fact that Sam's voice was not heard in this vicious battle was lost on the jury. They preferred to believe that Sam had engaged in an argument with his wife and had killed her without raising his voice.

Crucial– yet apparently ignored– testimony comes from neighbor Frank Massie. From his yard across the street, Massie testified that he didn't realize that anything was amiss until he saw Dr. Frank McCue run into Sam's house. A few minutes later, he noticed "a boy, a lad with a gray hat, or a light hat and dark clothes, run out of the lane [next to the McCue house] very fast, between Sam's house and Mr. Moran's, down Park Street towards town, south."

The "boy" that Mr. Massie saw may have been a 22- year-old woman. Had she disguised herself so no one would recognize her as she went to Sam McCue's house that night for a rendezvous? As Massie could not speak well enough to be understood, he did not attend the trial. Instead, he submitted a handwritten note to the court about the events he witnessed that night.

The note was entered into evidence and mentioned in closing arguments, but it couldn't stop the tide rolling against McCue. Had Massie been able to speak clearly and had he attended the trial, perhaps questions on cross-examination would have raised discussion of this "boy." Perhaps someone else would have come forward who had seen this figure run through the night towards Court Square on the most infamous night in the town's history. Perhaps someone even would have recognized her and put two and two together.

Reporters of the day, who had "solved" the murder within 24 hours of the crime, did not make much of the sighting of some mystery person running from the scene.

The second killing

After 18 minutes of deliberation, the jury foreman read the verdict, "We the jury find the defendant guilty as charged in the indictment for murder in the first degree." McCue was to be taken, on January 20, 1905, "between the hours of sunrise and sunset, to some place within the closure of said jail, and by said Sergeant be hanged by his neck until dead."

McCue's lawyers asked the Court to set aside the verdict due to errors of evidence and because the jurors were permitted to read the newspapers, but the Virginia Supreme Court denied Sam's appeal only two days before his scheduled execution. Governor A. J. Montague, however, did postpone it until February 10.

On the day before her father's execution, Ruby McCue, Sam's 13-year-old daughter, made a tearful, passionate appeal for her father's life in Richmond. On the night Governor Montague denied her plea for clemency, Ruby made her last visit to her father. Young Ruby was hysterical as the four children gathered at the jail just two blocks from their home. Sam begged to have his children allowed to spend his last night with him, but this too was denied. Sam kissed each child goodbye and settled down to await the dawn.

Sam's will, hand-written in pencil, divided his estate among the four children. He had taken out insurance policies, with Fannie the beneficiary of most, totaling over $70,000. Sam appointed four of his brothers as guardians of each of his children. His worldly affairs were in order.

On Friday morning, February 10, 1905, Sam had his last meal: steak, eggs, and coffee sent from the Iroquois Restaurant on Main Street. He did not eat much as he talked with three local ministers about things spiritual.

At the appointed hour, his hands were bound behind him, and he was led into the freezing jail yard. After mounting the scaffold, Sam was asked if he had any last words. He answered politely, "None at all."

Samuel McCue lived here and died here

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The City of Charlottesville congratulated itself on the afternoon of February 10 when it read in a special edition of the Daily Progress that J. Samuel McCue had confessed to his crime just hours before he was hanged. With a collective sigh of relief, the citizens could go about their lives knowing that they had done their duty.

But let us look carefully at Sam's "confession." Being an attorney, he always chose his words with care. His last words before the judge, after his conviction: "I am as innocent as any other man in the courtroom."

Then before going to the gallows, he allegedly made a confession.

J. Samuel McCue stated this morning in our presence and requested us to make public that he did not wish to leave this world with suspicion resting on any human being other than himself; that he alone is responsible for the deed, impelled to it by an evil power beyond his control; and that he recognized his sentence as just.

Signed: George L. Petrie, Harry B. Lee, John B. Turpin

Are we to believe that a guilty man, just hours from death, was worried that someone else might later be suspected of the crime? He had been tried and convicted of it. What would make him worry that after his death anyone would look for another suspect, thereby proving their own mistake? Who would take responsibility for such an error, and why would Sam care?

One reason could be that Sam knew who the actual murderer was and that she was still at some risk. He could no longer save himself, but he could still protect his lover.

Moreover, Sam's confession doesn't say that he killed Fannie, but that he was "responsible" for her death. Indeed, his philandering ways may have led to her death. Sam and Fannie could both have been victims of his deranged lover.

***

Things returned to normal in Charlottesville. Sam's brothers remained prosperous and respected members of the community. Sam's children drifted off to parts unknown, probably to escape the notoriety of the murder case. Orphaned and experiencing the taunts of other children as they were, their lives in Charlottesville could not have been easy.

Life could not have been kind to Hattie either. She left her husband and moved to Washington, D.C., taking with her the illegitimate son of the man who was executed for a murder she may have committed. Her husband sued for divorce in 1915. No more is known of her.

***

Nearly three years after the execution, the body of Sam McCue was moved from his parents' home in "Brookeville," an estate at the foot of Afton Mountain, and re-interred in Charlottesville's Riverview Cemetery next to the body of his beloved Fannie. (While only her headstone stands at Riverview, cemetery officials confirmed for this reporter– via a metal probe of the soil– that there is a burial vault or casket to the left of her grave, on the "husband's" side of the plot.)

Fannie's tombstone in Riverview Cemetary

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

***

The foyer of the McCue house is still as it was 100 years ago. The pocket door to the parlor is still there, tucked into the wall as was the fashion in Victorian houses in that day. There is no phone on the right at the entrance to the parlor, and some additions have been made. But otherwise Sam and Fannie would recognize the house if they were to walk in the front door today.

The dirt lane bordering the south of the house is now a paved street called Parkway. About 100 feet from the bathroom window where Fannie died, across that lane, lived the Morans' black servant, Charles Skinner. There, in his bungalow, on a calm summer night, Skinner heard no man's voice.

Some say the ghosts of Sam and Fannie McCue still walk through the house on Park Street. Fannie's presence is usually noticed upstairs where she was killed, while Sam's is said to occupy the basement. Sure enough, a recent tour of the house found the claw-footed bathtub in the basement; the upstairs bathroom, where the murder occurred, is now a bedroom but one that, according to Comyn Hall's director, is always empty because no one wants to stay there.

Some people believe that ghosts are spirits that cannot rest until some injustice has been corrected. Sam and Fannie, rest in peace.

***

"Gentlemen, gentlemen, there is some mystery here. Something that we don't understand." –Defense Attorney G. B. Sinclair

Vinton H. Valentine, the 12-year-old boy who witnessed the hanging from High Street on that cold February morning in 1905, would later buy a house across from the McCue place to become the fourth generation of Valentines to live on Park Street (his son would later become the fifth). Yet even after his death in 1968, Valentine's connection with the event continued. In 1990, his widow, the late Irene Valentine, moved into the old McCue house and occupied the bedroom that Sam and Fannie McCue shared until that fearful night.

An earlier version of this story appeared in another local paper in 1996.

Well, it wasn't Professor Plum in the conservatory!

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The tub in which Fannie died now rests in the basement.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The murder scene is now a bedroom, but it's so unpopular that it remains empty.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Looking west down the hall at Comyn Hall, aka chez McCue.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"Go find Fannie," the wounded Sam McCue, sitting on these steps, allegedly asked his brother.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#