Tobacco town: Smokers, sellers defy Healthville docs

"Crops may fail, commerce stagnate, wars devastate the country, banks suspend specie payment, and wives fret and scold, yet our people will chew and spit, smoke and puff, snuff and sneeze."– C.L. Thonpson, 19th century Albemarle citizen

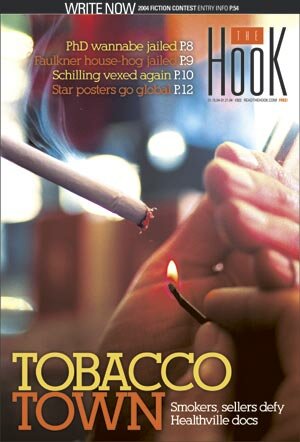

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Charlottesville, with its runners, its bike lanes, its natural food stores– even a veggie fest and national recognition for healthy living was named healthiest city in Virginia by Organic Style magazine and most energetic by USA Weekend. But a decidedly unhealthy activity is alive and well even flourishing– here, say local tobacco merchants.

Most Americans– particularly the educated types around Virginia's flagship university– know the health risks involved in smoking tobacco products. And still they smoke.

Who are Charlottesville's smokers? How and what do they smoke? Who welcomes their habit, and who scorns it?

We decided to find out.

THE HIGH SCHOOLERS

"The people who do it think it's so cool," says Western Albemarle student Ryan Houseman, 16. "Most of the other people don't like it."

Houseman himself is not a smoker; he considers the habit "gross."

Houseman agrees with others who observe that "it's mostly poor kids" who smoke. And, according to Houseman, most of such underage smokers obtain cigarettes by stealing.

Ryan Houseman

Chewing tobacco is extremely popular these days with "the same people who smoke," Houseman notes. "There's a guy who rides my bus," he relates, "and I know he's not very rich or anything. He chews tobacco on the bus, and it's really gross."

Like smokers, the high schoolers who "dip" often practice their habit in the bathroom. And they have terrible aim.

"They cover the toilet seat," says Houseman, "so you can't even go to the bathroom anymore. There's also cigarette ashes in there."

But he believes pot smoking has eclipsed cigarettes in popularity among adolescents. "They talk about it, and they do it in school," he says. Some students are even more brazen: "There was a guy in one of my classes who rolled two blunts in the middle of class," Houseman says.

Can we expect parents soon to be pleading with their kids to return to smoking– tobacco?

THE CIGARETTE MERCHANT

In two decades spent working in places on the Corner, most recently part-time at the Corner Market, Paul Jones, 55, has seen endless packs of cigarettes, cigars, and pouches of pipe tobacco change hands. How do Charlottesville residents smoke?

"People seem to try to keep it to a minimum, I've found," he says, "or smoke lighter cigarettes, for health reasons."

Paul Jones

Since the '70s, a distinct smoking trend Jones has noticed is the near disappearance of unfiltered cigarettes. Despite their former popularity, the Corner Market now carries only three unfiltered brands: Camels, Pall Malls, and Lucky Strikes. But sales of those old time favorites are a distinct minority today, like the people who buy them: "Mostly older men are smokin' 'em they've been smokin' 'em for years," Jones says. The Marlboro Man lassoed them and never let go.

UVA students rank among the Corner Market's steadiest cigarette customers. Student favorites are Camel Lights, followed by Marlboro Lights. (Note: UVA's Center for Drug and Alcohol Education reports that 70 percent of all UVA students they surveyed stated that they had not used any tobacco products in the 30 days preceding the survey.)

Smoking "light" cigarettes is a persistent habit among student smokers an indication in its own way, perhaps, of Charlottesville's widespread health-consciousness. "Very few of 'em smoke full flavor, and almost none of 'em smoke unfiltered," Jones observes.

Within the community, Jones says, "Newports are huge."

Low-end cigars, like Phillies Blunts and Black and Milds, sell well. "Rolling your own" also remains fairly popular: The Corner Market has "a steady clientele" for "a lot of upper-end rolling tobacco," says Jones. Clove cigarettes are the most popular of the imported varieties they stock.

Jones can determine no clear-cut demographic among Charlottesville's smokers. Who smokes the most? "Everybody! We have a lot of students, a lot of blacks, a lot of whites, blue-collar workers, office workers. Seems pretty widespread, right across the spectrum." As far as Jones can tell, the split between male/female, younger/older smokers is even.

Has America's lagging economy trickled down to cigarette sales? "The price of cigarettes just keeps going up, and it doesn't seem to hurt," muses Jones. "They just keep smoking."

THE CIGAR MERCHANT

Jim Robinson, 63, opened Cavalier Pipe and Tobacco downtown on May 19, 1975, and relocated to the Barracks Road Shopping Center five years later. He is well versed in the smoking habits of Charlottesville's more affluent citizens.

Unlike cigarettes, cigars have undergone a tremendous upswing in popularity since the '70s and '80s, days when Robinson had to sell gifts to make up for sluggish cigar sales, he says. The electricity to run his humidor's air conditioner cost more than Robinson was making each day from cigars.

Jim Robinson

Despite cigar dealers' initial disinterest, Cigar Aficianado magazine debuted in 1992, prospered, and earned cigars newfound popularity and respectability. The magazine became a worldwide top-seller. By 1994, cigar sales began to skyrocket.

"In the '90s, everybody had to get into cigars," Robinson recalls, with a decided Arkansas twang. "That was the thing to do."

A boom occurred between 1994 and 2000. Robinson had customers who were spending as much as $40,000 on cigars annually. Cigars are still popular enough to allow him to carry approximately 950 different brands. Pipe tobacco is another of his big sellers.

The escalating popularity naturally sparked price hikes. There were other contributing factors: higher wages for South American cigar rollers, rising tobacco taxes, and shoplifting.

How massive were those price hikes? Robinson has a Dunhill that retailed for an extravagant $1.25 in 1976. That same cigar now runs $13.

But since 2000, sales have leveled off.

Robinson sells to customers "from all walks of life," he says. "Some are people of modest means," while others "have about as much money as God would have if God had money," he says. Cigars, though, are still mainly a luxury item for the affluent. "For the average person," says Robinson, "ten or twelve dollars is a lot of money to watch burn up in an hour."

Despite the name Cavalier Pipe and Tobacco, UVA has no ties with the shop. The store's sign formerly featured a small painting of the Cavalier logo, and also sold a Zippo lighter featuring that same emblem. Since UVA holds the design's trademark, Robinson had to paint over the image on his sign, and Zippo discontinued the "Cavalier" lighter.

However, one UVA organization has for the past 27 years, "religiously" bought 400 cigars twice yearly from Robinson for various functions.

Women are seldom counted among the ranks of cigar smokers. Nevertheless, Robinson has a steady stream of female clients, many of whom are buying cigars for their husbands or boyfriends. "Surprisingly," he says, "they know exactly what they're buying."

In the final analysis, Charlottesville's smokers defy categorization. What they smoke is much more apparent than who does the smoking. At the very least, they represent one of Charlottesville's most democratic subcultures. Say what you will about their products, tobacconists discriminate against no one, except the underage.

Meanwhile, another question remains: Where do smokers go, and how do they behave when they get there?

THE RESTAURATEUR

Michael Crafaik, owner of Michael's Bistro on the Corner, is a major local mediator in the ongoing feud between smoking and non-smoking bar and restaurant patrons. At Michael's, smoking is mainly confined to the bar and is forbidden during dining hours. After 10pm, when the bar crowd takes over, "it's fair game," Crafaik says.

"We're a small restaurant," he explains, "and it's not feasible for us to have a smoking room and a non-smoking room. We'd do that if we could, but pretty much because it's one big room, the only area that's off by itself is the bar.

"It seems civilized enough," he says of the slight effort required of smokers to "get up from your table, go over to the bar, and smoke your cigarette."

He has noticed that smoker/non-smoker relations have "reached a good level of respect, where people aren't blowing smoke in each other's faces. I think it's evolved just fine," he says.

Crafaik essentially has no choice but to allow smoking at his bar, something that he says he considers an economic necessity since "drinking and smoking go hand in hand."

The nightspot that preceded Michael's in its present location was a non-smoking jazz club, which rapidly discovered what a prerequisite smoking is in bars.

"A lot of people thought that was really just a great idea," Crafaik says, "'Wow! no smoking!' You don't have to go out and have your clothes stink the next day." But the club folded about a year after opening. "The bottom line is the people who go out late at night and drink very often are the smokers," says Crafaik.

"Most bar people wouldn't feel that they could chop out smoking," he says, "because they'd be at a competitive disadvantage." Nor does Crafaik, a nonsmoker, favor the alternate solution: banning smoking "across the board" in bars or restaurants.

Michael's used to sell cigars, but "the hassle for me to go get them," says Crafaik, "was more than the profits they reaped." The stogies' only remnants at the Bistro are some mechanical "smoke-eaters" mounted among the ceiling tiles.

Diners seldom smoke pipes at Michael's, but there are one or two who do. This doesn't ruffle Crafaik: "I think pipes smell great," he says.

Crafaik is satisfied with the smoking situation at his watering hole. "I've had a handful of people complain about it and say, 'You should have no smoking at any time at all.' But you've got to accommodate people. And I think we've got a pretty reasonable middle ground."

THE BAR MANAGER

Rapture remains one of the most smoking-friendly places in town. Patrons can smoke cigars, pipes, clove cigarettes anything allowed by law.

But Rapture manager, Jessica Wilkin, 25, believes that the policy hasn't made the spot a magnet for smokers. Why is Rapture so much freer with its smoking policies? "Because we're a bar," she says succinctly, "and you can't have a bar without having smoking.

"I believe a lot of people who do frequent bars are smokers," she continues, "including a lot of the staff."

Jessica Wilkin

There are those who complain, she says, "because we do tend to have a lot of smoke. People will ask me, 'Oh, is it smoky inside?' And, frankly, I can't tell you, because I'm always in it. We don't get an overwhelming number of complaints."

However, she notes that some of Rapture's more sensitive diners do complain as smoke wafts their way. But "the non-smokers who do come in and hang out in the bar area understand that there's gonna be smoking."

A nonsmoker herself, Wilkin says that she often sees smokers behaving somewhat gallantly towards non-smokers: "They will move so that the smoke from either their cigarette or from their blowing it out doesn't come towards you. Because, inevitably, whichever way the air system works, the smoke's gonna blow one way. They even do that for fellow smokers, too, because anybody who's not smoking doesn't want smoke coming right at them."

Cigar smoking was temporarily banned at Rapture during dinner service, but, "as soon as I got into the position of the management," Wilkin says, "that was one of the things I changed. I think it's important for people to know that whatever you smoke, we're not going to say, 'Oh, we're sorry. You can't do that.'

"Why should we allow one form of smoking, and ban others?" she asks.

Pipes rarely appear at Rapture, she says.

Wilkin thinks that if Rapture were to ban smoking, it would definitely hurt business. "If you go to a bar, you expect that you're going to be allowed to smoke, unless you're in California or New York. And we live in the heart of tobacco country," she notes. She predicts that Virginia will be one of the last states to pass such legislation.

But there's always the other side. Though tobacconists and restaurateurs may be staunch allies of smokers, they have no greater opponents than folks in the medical professions. The Hook spoke with two people whose careers put them in close proximity to the devastation that smoking can work on the human body.

THE DIRECTOR OF THE UVA CANCER CENTER:

Michael Weber is one among many who would love to see Joe Camel ground up and used as a three-course Taco Bell dinner. As director of UVA's Cancer Center, why shouldn't he?

When asked if smoking cigars or pipes is less harmful than smoking cigarettes, since no inhalation occurs, Weber, 61, replies without a trace of humor, "I've got a wonderful picture of a tongue cancer that I'd be happy to show you.

"That was from a chewer," he continues, "but the same kind of things happen to other tobacco users.

"I mean, tobacco products that are burned or chewed are just a fantastic source of cancer-causing compounds. And if you want to bathe your body tissues in that, then that's what you do. The mechanism of application is secondary."

Michael Weber

Lung cancer, the affliction most often associated with smoking, is the most common killer of men and a major killer of women. This is because, says Weber, it's "essentially untreatable." Other forms regularly linked with smoking are cancers of the head, neck, and even the bladder.

Weber is as fascinated as anyone by the fact that some smokers live well into their 70s and 80s, while we've all heard of a nonsmoking jogger who keels over from a heart attack at age 40.

"There clearly are genetic factors," says Weber, "but I don't think that all of the issues are known. Your body has enzymes that detoxify some of the chemicals in tobacco and render them harmless. And the level of those enzymes varies from one individual to another.

"I think a valid area for investigation is to find out who among tobacco users is really susceptible to disease, and who could probably do it with impunity, or do it with minimal risk."

Smoking has become less popular overall in the last 40 years, according to the Center for Disease Control's Office on Smoking and Health (cdc.gov).

Nipping future smokers' habits in the bud is equally important, Weber feels. He has seen that "one of the most effective ways of decreasing smoking in kids is to increase the cigarette tax." Since blue-collar smokers far outnumber white-collar ones, he says, "some of our political figures" have opposed cigarette taxes because they would disproportionately affect lower-income Americans.

"I would argue," he says, "that it disproportionately helps lower income people to avoid a dangerous addiction."

Weber concedes that smoking offers "certain pharmacological benefits." Nicotine, for instance, aids concentration. However, he sternly concludes, "The effects– whether it's cancer or emphysema or bad breath or stained teeth or burned mattresses–seem to far outweigh the very modest pharmacological benefits."

THE ORTHOPEDIST, A "BORN AGAIN NON-SMOKER"

After smoking for 10 years, orthopedist David Heilbronner now considers himself a "born again non-smoker." This physician's revulsion at smoking may surpass even C. Everett Koop's.

Heilbronner is privy to the startlingly high number of orthopedic ailments that smoking can cause. Smokers are six to eight times more likely to develop back ailments, Heilbronner notes. And if a smoker refuses to quit after back problems appear, healing will be significantly slower than for a non-smoker with the same problem.

David Heilbronner

Smoking seriously affects the production of collagen, a substance essential to tissues, bones, and ligaments. One of the many studies Heilbronner cites indicates that "smoking one cigarette essentially stops the production of collagen for about 30 to 40 minutes." Ailing smokers "heal or have healing capability only when they're sleeping– in other words, when they're not smoking."

This fact has led many surgeons to refuse to perform plastic surgery or operations that involve re-attaching severed extremities for smokers "because the healing rate is so abysmal."

"Those who do," Heilbronner says, "often feel that it's not worth all the anxiety to the patient and the surgeon about getting things to heal."

Heilbronner calls second-hand smoke a menace that's "probably as bad and in some cases even worse– than direct smoke inhalation." Chronic smokers develop a tolerance for all the poisonous chemicals in tobacco smoke, he says. Non-smokers, lacking that tolerance, are more vulnerable.

On a personal level, Heilbronner speaks for many disenfranchised locals who have had their nightlife affected by smoke. "I don't go to Miller's at all anymore," he says, "because you can't breathe in there." Even leaving the main smoking area didn't help, he mourns. "It was just miserable. My eyes were watering and I was getting wheezy." (It should be noted that the new management of Miller's recently added a non-smoking section.)

The "whole question of sensitization to smoke," as Heilbrenner puts it, can be traced to the immediate response of most people to their first puff: severe coughing. "It's like the body is saying, 'What are you doing to me?'" he says.

Heilbronner is astounded by Charlottesville's young people who are willing to ignore the well-documented dangers of tobacco use. And he doesn't mean junior high and high school smokers who take up the habit as a way to rebel or look suave. "It amazes me to walk around the university and see the number of supposedly bright young people who are smoking like crazy. I don't get it," he says. [See sidebar on why smart women smoke–editor.]

Heilbronner disputes the notion that prohibiting smoking in all restaurants will hurt business. In most states, 75 to 80 percent of the populace are non-smokers, he says, and "that's obviously a huge number of people who may or may not go to restaurants because of intolerable levels of smoke in them."

Heilbronner issues a challenge to area eateries: "I'd like to encourage more local restaurants to make their dining rooms smoke-free. I think they will, in the long run, find more business from the number of people who are tending to stay away.

If health issues and consideration of fellow diners aren't enough, Heilbronner appeals to vanity: "Young people, when they walk around town, should look at old smokers and realize that most of them are probably younger than they look."

As for Virginia's two-and-a-half-cents-per-pack cigarette tax, the lowest in the nation, Heilbronner says, "I think our legislature should be ashamed of itself for the way they've let themselves be manhandled. I think many of them are cowards not to stand up basically for the health of the citizens of Virginia."

Heilbronner seems to support Governor Mark Warner's proposal for increasing the tax to 25 cents a pack, noting that the higher cost might deter some people from beginning to smoke.

"Certain members of the legislature try and pass a bill, but then it gets knocked down. Richmond needs to get its act together and do what's good for everybody in the state, not just the tobacco industry," he concludes. #