This boy's lawsuit: Alan Newsom's $150,000 t-shirt

Alan Newsom looks like a pretty typical 13-year-old. He wears standard eighth-grade garb– the backwards baseball cap, baggy, low-slung jeans, and a t-shirt.

It's the latter item of apparel that propelled Newsom into court and provoked a precedent-setting decision on school policy and the First Amendment.

Two years ago, when he was in the sixth grade at Jack Jouett Middle School, Newsom spent the weekend at an NRA Shooting Sports Camp learning about rifle target shooting and gun safety. Jazzed about the camp, he wore its bright purple t-shirt to school on April 29, 2002.

But once he got there, he was asked to remove it. That request led to a lawsuit against the Albemarle County School Board, the superintendent, and principals at Jouett. Backed by NRA legal muscle, Newsom claimed his First Amendment rights had been violated and sued for $150,000.

After two years and major setbacks for Albemarle– including a ruling allowing Newsom to wear the shirt– the suit went into mediation last Thursday, January 22, and a settlement could be announced by the time this issue is on newsstands.

A seemingly routine decision by a Jouett assistant principal in the post-Columbine era collided with free speech issues. Not only will Newsom v. Albemarle School Board affect how the county sets dress code policy, but it encompasses every other school system in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina– states under the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

"Disruptive" attire

The job of a middle school assistant principal is largely disciplinary. Betty Pitt has held that post at Jouett since 1991. As Pitt scanned the cafeteria that Monday in April 2002, Newsom's purple shirt caught her eye.

His back was to her, and she noticed "three large and bold graphic images of human figures holding and/or pointing firearms," she said in an October 2002 affidavit.

Pitt thought the images could be interpreted by other students as promoting the use of guns, conflicting with the school's message that "guns and schools don't mix." She believed that because they were so "distracting," the graphics "had the potential to disrupt the instructional process."

In addition, Pitt claimed in her affidavit that the silhouettes reminded her of several school shootings, including the 1999 massacre of 12 students and a teacher at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, by two students who subsequently killed themselves.

Pitt approached Newsom and whispered in his ear that the shirt was not appropriate school attire. She suggested he change it or turn it inside out.

He replied that he'd gotten it at camp, and asked what was wrong with it.

She told him the shirt was inappropriate because of the images of men shooting guns. In a point that would later be challenged, Pitt told him the school dress code didn't allow images of weapons.

Pitt had long considered Newsom "an obedient and cooperative student." When he asked what would happen if he didn't remove the shirt, she told him his disobedience could result in an in-school suspension.

He went to the restroom and wore his shirt inside out for the rest of the day.

The plaintiff

In the two years since Newsom was forced to remove his t-shirt– "partially disrobe" is how it's described in the lawsuit– he and his father, Fred, have become more media savvy. They know, for instance, to bring the controversial t-shirt along to interviews without being asked.

Fred Newsom worries about Alan being photographed with his baseball cap on backwards because he doesn't want anybody getting the wrong idea about his son and thinking he's a gangsta or something, even though that look is standard attire for plenty of friendly suburban teens.

When he's not suing the county, Alan is active in his church. He likes to play paintball, ride his three-wheeler on the track his brother made, play on his computer, watch TV, and hang out with friends.

He has a dog, a gecko, and a foot-and-a-half-long bull python– because, he explains, "my parents won't let me get a bigger one."

When he grows up, Alan wants to go to college, enter the Air Force, and ultimately become an airline pilot. He mentions a birthday gift of a 30-minute plane ride, made even more memorable because he got to steer.

"Alan is very clean cut, a good kid," says his NRA attorney, Dan Zavadil, who'd asked if Alan had been in trouble before he took the case. "He's an average 13-year-old who enjoyed target shooting."

The Shirt

For probably the umpteenth time, Alan tells why he wore The Shirt.

For one thing, he was excited about shooting a rifle at the NRA camp, where he'd gotten five shots through one hole. "I wanted to wear it to tell people to go, to tell my friends it was fun," he says.

The Shirt was brand new, and it was the first time he'd worn it. "There were no disruptions until lunch, when Ms. Pitt told me to go to the bathroom and turn it inside out. I was walking around the halls with my shirt inside out. That was more of a disruption, because kids were coming up to me about it. It was really embarrassing," he says.

He went home, told his parents, and asked his mom what kind of protest he could do. He collected around 100 signatures on a petition, but "some of the kids who signed it didn't want me to turn it in with their names on it," he says.

Fred Newsom, who did target shooting when he was Alan's age, admits that his personal inclination would be to just wear another shirt.

"But I recognized what an important principle this would be," he says, "and Alan was upset."

"I wasn't crying or nothing," Alan interjects.

"He went in proud, representing his interest," continues Fred. "He was mad at being singled out. That's one thing a sixth grader doesn't like, being singled out."

One other thing troubled the Newsoms. "We'd combed through the rules and found no violation," says Fred.

The Jouett Student/Parent Handbook prohibited "messages on clothing, jewelry, and personal belongings that relate to drugs, alcohol, tobacco, sex, vulgarity, or that reflect adversely upon persons because of their race or ethnic group."

Nothing about images of weapons.

Fred Newsom emailed the NRA's Youth Shooting Division to ask if they'd ever had a problem similar to what Alan had experienced and if they had any suggestions.

NRA attorney Zavadil did have some suggestions. He wrote the school May 31, 2002, pointing out that there was no rule that prohibited The Shirt, and asked for reconsideration and an apology.

"On June 17, they responded, citing a nonexistent rule," says Zavidil.

"Their response was to change the dress code," says Fred Newsom.

During the summer of 2002, Jouett revised its handbook to prohibit messages relating to "drugs, alcohol, tobacco, weapons, violence, sex, vulgarity...," etc.

Says Zavadil, "I feel like I was lied to."

"They got hard headed, and we got hard headed," says Fred Newsom.

Changes in latitude

On September 17, the Newsoms filed suit against the Albemarle School Board, Betty Pitt, former Jouett principal Russell Jarrett, and superintendent Kevin Castner, seeking $100,000 in compensatory damages and $50,000 in punitive damages for alleged violation of Alan's First Amendment rights.

In court on October 2, 2002, Zavadil asked for a preliminary injunction to prohibit authorities from enforcing the Jouett dress code so that Alan could wear the shirt while the case was being decided.

That December, U.S. District Court Judge Norman Moon ruled against Newsom, agreeing with the school district that the case was about student conduct, not speech, and therefore not entitled to First Amendment protection.

Three key Supreme Court decisions concern a school administration's ability to deal with speech it considers disruptive.

In 1965, three Iowa students were suspended for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. In Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969, the Supreme Court upheld the right of students to symbolic expression. "In the absence of a specific showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views," wrote Justice Abe Fortas.

Albemarle's attorneys argued the case fell under two other Supreme Court cases that give school administrators more latitude in regulating disruptive speech: the 1986 Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser decision, which allowed schools to control student speech that was inconsistent with school policy– in that case, a bawdy nomination speech– and the 1988 Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier decision that ruled a principal could censor a student newspaper.

The two sides lined up amicus briefs. Those agreeing with Alan's First Amendment argument included the ACLU of Virginia and the state attorney general's office, which noted that the school's policy would ban many Virginia symbols, such as the state seal (with its semi-nude female warrior holding a spear), and UVA's crossed-saber sports logo.

The National School Boards Association supported Albemarle's position. "It was one of those cases that present a typical situation school systems face, trying to draw an appropriate balance between free speech and maintaining a learning environment," says Association staff attorney Naomi Gittins.

The appeal

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit disagreed with Judge Moon's decision twice.

In early December 2003, the appeals court said the Jouett dress code was "unconstitutionally overbroad" and that the district court had "abused its discretion."

Alan could wear The Shirt.

Albemarle requested that the appeal be reheard by all 14 judges on the Fourth Circuit. On January 6, 2004, the appeals court unanimously denied the school board's petition and refused to hear the case.

Says Zavadil of the county, "They never cease to slay me with their desire to continue this fight."

The NRA is no stranger to defending rights under the Second Amendment ("the right to keep and bear arms"), but Zavadil sees this wholly as a First Amendment case.

"We're opposed to the politically correct culture trying to get rid of images of weapons and treat them as evil," he says. "Just because you see a weapon, it doesn't mean it's violent or threatening."

He lists the other images that would be prohibited by the Jouett dress code, including the mascot logo of Albemarle High School next door: a patriot with a musket.

"This is a case of political correctness run amok," he declares.

Fallout of the fight

"As a school system, we very much disagree with the [appeals] court decision," says deputy county attorney Mark Trank, the county's point-person on the suit. "A decision whether to appeal has not been made."

Trank maintains that the county, which he says handled the case properly, hasn't thrown in the towel on the original point of the lawsuit: Newsom's claim that his First Amendment rights were violated when he was required to turn his shirt inside out.

"That issue has not been decided," Trank says.

Albemarle's doggedness in pursuing the case has drawn some criticism.

"It's ridiculous to spend taxpayers' money on something like that," says Conservative Coalition founder Peter Way. "It's just Albemarle County with its political agenda. Albemarle County schools never, ever admit they're wrong."

Fred Newsom, too, is concerned about the cost of the lawsuit. "I went through a period feeling guilty about our tax dollars being spent, given the need for teachers' salaries, textbooks, and expansion," he says. "They're the ones who chose to use resources on this."

The Newsoms are also looking to collect attorneys' fees, which the NRA estimated in mid-January to be in excess of $127,000.

The county's costs so far are not actually coming out of the its beleaguered budget, according to Trank. The school district's liability insurance covers the litigation, and the county has to cough up only its policy's $1,000 deductible.

"All the costs of the defense and damages are covered," explains Trank. "They are not seeking damages that exceed the maximum. There's very little out-of-pocket expense for the county."

All the Albemarle School Board members sitting in 2002 are named in the suit, but not all agreed with the decision to fight. Says former board member Gary Grant, "I think the school board, the school division, and the administrative staff dug in our heels on an issue we shouldn't have."

Grant supports in general a school's right to determine whether student attire is disruptive, and says, "I believe that what Betty Pitt did was in good faith."

But The Shirt didn't bother him. "For God's sake, this kid went to legal, formal, shooting camp where they teach gunmanship and safety," he exclaims. "If the shirt had said, 'Blast the hell out of all teachers,' I'd be bothered."

So why did the school system pursue the case? "We were given legal advice that we were in the right, that we had a good case," he replies.

Grant also criticizes the school system's failure to communicate to the public what was going on with the lawsuit. The county has since hired a part-time communications specialist, but Grant still worries that press releases will be more about covered-dish suppers than controversies.

And while the National School Boards Association backed Albemarle's decision to assert its right to determine dress code, the Virginia School Boards Association is more circumspect.

"Our advice would have been to not appeal it and handle it in another way, and save those attorneys fees," says VSBA executive director Frank Barham.

"The courts have said you can't speculate that what a child wears will be disruptive," he adds. "It actually has to be disruptive."

Because Albemarle is a member school board, and the national organization backed Albemarle's position, "Our job is to support them," says Barham. "Because of the recency of Littleton, we felt better to err on the side of safety."

But he notes, "This is one of those borderline cases that you never know how a judge will rule."

And while National School Boards Association's Gittins thought Albemarle had a strong case, she wasn't surprised by the Fourth Circuit's decision to slap down the lower court, except for one aspect.

"The Fourth Circuit is usually supportive of schools," she observes. "This is a little bit of a departure from that."

Well-known zero-tolerance opponent and Rutherford Institute founder John Whitehead commends the appeals court.

"The Fourth Circuit is going against the grain," says Whitehead, explaining that the lower the grade level, the more likely courts will rule in favor of a school's safety or disruption arguments.

Whitehead lauds this decision for applying "a strong constitutional standard" for middle-school students and mentions a similar case in Colorado, where the Rutherford Institute is about to sue. "A kid wearing a Marine Corps logo rifle is suspended. They put him in a room with a Marine recruiting poster with guns charging."

The ability to show support for the military is something both Newsoms remark upon.

Alan Newsom is bothered by the message the county's stance sends about hunters or people whose job involves guns, like cops or soldiers. "They're saying they're bad," he says.

"I think zero-tolerance policies are a way to absolve schools from making commonsense decisions," Fred Newsom says.

And he thinks the case is politically driven. "I like Ms. Pitt," he says. "She's very good in doing a difficult job. But I think she injected a personal opinion about shooting sports where it's not appropriate to do so."

Pitt did not return The Hook's phone calls.

Dust settles

Once the parties sat down to settle last January 22, neither side could comment on how talks were progressing.

But before the mediation session, Jack Jouett Middle School was already taking steps to revise its dress code to take into account the concerns raised by the Fourth Circuit, according to Trank.

In Albemarle County, there's no central dress code; each school adopts its own. Those days may be ending, he says. "Most administrators feel that would be unfortunate because the school policy has always worked well," he says.

Another unintended consequence that could loom in county school students' future? "When students file lawsuits over clothing, one of the considerations school boards make is more standardized dress," says Trank. "One of the extremes is school uniforms," but he believes that's unlikely to happen here.

Fred Newsom repeatedly says the lawsuit could have gone away had the school simply apologized. But as they headed to mediation, he was less willing to settle for a "sorry."

"At every turn, they've put in for as many delays as possible," he says. "They've been very intractable for two years. Right now, I feel unless there are consequences for that intractability, they might treat the next kid the same way."

Trank defends the county's handling of The Shirt. "This goes to the heart of a school's ability to preserve a safe learning environment for all students," he explains.

"Most courts are receptive to the needs of school officials to operate their schools without the interference of the courts. It was the belief of school administrators and my belief that the assistant principal acted appropriately."

"Any school system could face that," says Charlottesville school superintendent Ron Hutchinson. The former high school principal believes there's a context to what happened at Jouett: "Unless you're sitting there, you can't judge."

Today's lesson

On the eve of mediation, Fred Newsom worries that Albemarle's settlement offer might include a nondisclosure provision– more commonly known as a gag order.

"I think it's wrong to take a Michael Jackson position– to take the money and shut up," he says, referring to Jackson's settlement of an early 1990s lawsuit alleging molestation. And certainly that would be ironic in a free speech case.

Alan Newsom doesn't appear to have suffered a backlash from suing his former principal and assistant principal. He really likes Jouett, and he says classmates ask him all the time how the suit is going.

"Everybody's on my side," he says. "They say it's stupid."

"Ms. Pitt is really strict about the dress code," says Jouett eighth-grader Sarah Teplitzky. "Most kids want to see him win."

She adds, "It's his hobby. It's not like he's going to shoot people."

Teplitzky had her own run-in with Pitt over attire when she wore a t-shirt from French Connection UK that had the initials "FCUK."

"I was avoiding her all day," says Teplizky. "She yelled at me at the end of the day and made me put on a jacket."

Newsom acknowledges that the parents of one of his friends do not support his suit. "They think it's wrong I'm suing the school," he says, "because there's so much violence."

As the youngest of three children, "Alan has learned to stick up for himself," says his father. "When somebody picks on him, he stands his ground. As a father, I felt I had to stand up for him."

And did Fred push Alan into filing suit? "No, not at all," says Alan.

"I hope nobody thinks that," says Fred.

Another lesson Alan has learned about the legal system is how slowly it moves.

Despite his appeals court victories, Alan, so far, has not again worn The Shirt to school.

"We felt his going in on the first possible day flaunting his shirt was not the good sportsmanship they taught in Little League," says Fred.

In fact, Alan won't be wearing The Shirt at all. Because in between learning about First Amendment issues and how slowly the wheels of justice turn, one other thing happened: He's outgrown The Shirt.

But that's okay. He's got plenty more.

Alan Newsom's civics lesson so far has not come up in class discussions at Jack Jouett Middle School.

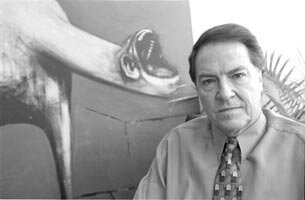

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Investment consultant Fred Newsom likes target shooting– but hunts with a camera. He thinks the Albemarle school district has an anti-Second Amendment political agenda.

Investment consultant Fred Newsom likes target shooting– but hunts with a camera. He thinks the Albemarle school district has an anti-Second Amendment political agenda.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

An appeals court called Jack Jouett Middle School's dress code "unconstitutionally overbroad."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

With a war going on in Iraq, the Rutherford Institute's John Whitehead calls school policies that ban images of weapons "schizophrenic."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Jouett's neighbor, Albemarle High, has a gun-toting patriot for a mascot.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#