Recent passed: Will groovy structures be landmarks?

When Best Buy came to town last summer and demolished the Mount Vernon Motor Lodge and the adjacent Aunt Sarah's Pancake House, Charlottesville resident Christine Madrid French realized her town was losing more than just a few pancakes and a heart-shaped swimming pool.

While many locals welcomed yet another low-cost electronics emporium, French mourned the loss of legitimate pieces of Charlottesville history and the end of an era of tourist-oriented roadside architecture. "These buildings," says French, "have no protection at all."

She's on a mission to change that– or at least change a few minds.

As president of The Recent Past Preservation Network, a non-profit group established four years ago in Arlington, French wants to do some demolition of her own– she wants to smash the idea that a building must be 100 years old to be important.

"In Charlottesville, we mostly concentrate on 18th or 19th Century buildings," says French, who also heads up the Network's Charlottesville chapter. She wants to document newer jewels that many people may not recognize as valuable.

Her hot-list includes such unlikely landmarks as the K-Mart, the Aloha restaurant, and the Terrace Cinema. Each, she says, has something to teach viewers about Charlottesville– and perhaps American– history.

Consider the Budget Inn on Emmet Street. To some, it's just low-cost lodging at the foot of UVA's Carr's Hill. But in 1963, when few Charlottesville motels were open to African Americans, it welcomed Martin Luther King Jr. when he came to Charlottesville to speak at UVA.

"I know you can't save everything," says French. "But if an important person lived there, worked there, stayed there, at least we should slow the process [of demolition] down."

French, 37, and the local chapter of the Network have just embarked on a "windshield survey" of what they consider significant Charlottesville structures built from 1930 to 1979. While some might consider the notion of saving "historic structures" from the 1970s to be as funny as preserving polyester bell-bottoms from the same era, that is French's mission.

Mission 66

French is no stranger to missions. She's considered America's leading expert on "Mission 66," a mid-century push by the National Park Service for innovations in tourist services. The goal was ambitious: construct 100 new buildings in time for the Park Service's 50th anniversary in 1966. In a nation suddenly enamored with the idea of motor travel, the results of Mission 66 changed the American landscape. Before the ascendancy of the automobile allowed middle-class families to chart their own course for summer travel, French says National Parks typically offered tourists little more than a log cabin and a bathroom.

Mission 66, she says, created a new kind of building: the visitor's center, providing an auditorium, interpretive exhibits, bookstores, and staff offices in one centralized structure. The Park Service hired architects to build buildings reflecting the new post-World War II prosperity. In other words, starkly modern architecture.

Few recent preservation efforts have received more attention than French's effort to save the 1961 Gettysburg Visitors Center and Cyclorama. While the Park Service wants a new structure in another location, French's campaign has garnered international attention. The Cyclorama was designed by the late Richard Neutra, the architect who helped define the International Style in L.A. with his 1929 Lovell House. French has received letters of support from such notable architectural gurus as Frank Gehry, J. Carter Brown, and Robert A.M. Stern.

But back to Charlottesville.

What era is appropriate?

French admits to having felt a little traumatized last year when she saw a consultant's conceptual drawing in the City-funded Corridor Study for urbanizing the corner of Emmet Street and Barracks Road. The image showed the concrete-columned Bank of America, which she considers an authentic modernist building, morphed into an example of faux Jeffersoniana.

"If you look closely," says French, "you'll see the concrete columns are still there in the speculative drawing– topped by decorative capitals, of course– and the scale of the building is the same. But it has been magically changed to an image more appropriate to 'ye olde' Charlottesville."

To French, the idea of coating everything in red brick insults not just the memory of the Sage of Monticello, but anyone who wants to learn by looking.

While French can rest assured that that rendering carries no weight with the bank, she worries that many building owners don't realize what gems they own. Who can blame property owners? French says there's a "widespread refusal to acknowledge the significance of modern structures."

Sometimes, she says, it just takes a little time to put things in perspective.

Time heals

For some local architecture watchers, the apartment building at the opening of this week's cover story, The Lofts at McIntire, is not the prettiest one in town. When asked for comment, typically outspoken architect Brian Broadus would say only, "I don't want to take a gratuitous shot at some high school drafting student."

It turns out that the structure, with its base of rusticated concrete block with maroon clapboard above, was designed on a pre-determined footprint by veteran builder Tom Hickman and an architect who asked not to be named in this story.

In fairness to Hickman and the anonymous architect, it should be pointed out that this was a troubled project in which the original contractor allegedly quit the project after site-clearing began.

The structure's developer, Monroe Russell, says the tenants like the look, and he's heard "99 percent positive comments" about the design.

"There were a few negative thoughts about the color at first," says Russell. "Maybe," he concedes, "I don't hear too many negative comments because they don't want to present them to me."

The Lofts, completed in 2002 wouldn't be the first recent building without a fan club. Take Lewis & Clark Square, the prominent office/condo tower that crowns the western edge of the Downtown Mall. In 1990, less than two years after its completion, a local newspaper dubbed it the "ugliest building in town." Even modern architecture fan Richard Guy Wilson, a UVA architectural historian, has called it "awkward" and "post-modern."

We asked the project's lead architect, David Oakland, what he thought of the criticism. "We're very proud of what we built in that period of history," says Oakland, "and we'll let it stand at that." However, partner Bob Moje defends Oakland and the other three members of the design team, Bob Vickery, Jeff Dreyfus, and Brian Broadus.

"It was a developer building," says Moje. "What we drew and what we built weren't the same."

When pressed to name the ugliest prominent building in Charlottesville, Wilson says he dislikes the U.S. Post Office on Emmet Street, but that the federal building on Vinegar Hill is Charlottesville's worst. "That is the absolute nadir," he says, "the absolute bottom of governmental architecture."

However, Wilson won't rule out the idea that Lewis & Clark Square or the Lofts at McIntire might someday become classics.

"Times change," says Wilson. "Buildings we used to think are wonderful turn out to be awful– and vice versa."

What's an antique?

"Historic preservation has traditionally encompassed buildings that are older than fifty years," French writes in a recent newsletter for Preservation Piedmont. "But the focus is shifting as more buildings from our recent past disappear before they can reach that honored age."

Take University Hall. At 8,457 seats, "U-Hall" is the smallest basketball arena in the ultra-competitive Atlantic Coast Conference. Ergo, it's doomed.

"That's too bad," says professor Wilson. "It was a noteworthy building with novel engineering."

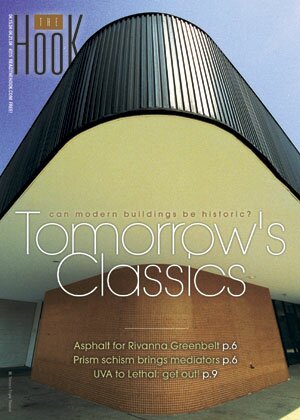

Designed by Anderson Beckwith with assistance from Richmond-based Baskervill & Son, U-Hall opened in 1965. Although generations of students have wisecracked that it looks like a "pregnant clam," some may soon clamor for its preservation. Meanwhile, its 15,076-seat, $129.8-million replacement– John Paul Jones Arena– rises nearby along Emmet Street in utter neo-traditional red brick with a pergola.

Hujafication

For over 30 years, city planner Satyendra Huja has shaped the look of Charlottesville. In just the past decade, he has helped create four new design control districts– bringing the City's total to six. Perhaps most controversial was his 1976 list of "individually significant properties"– nearly 100 structures outside the official historic districts that must be protected by force of law.

"I did that," says Huja, "because many of our historic buildings are scattered all over the City." He names the Fife family home, Oaklawn, just off Cherry Avenue as a prime example.

Huja says his favorite modern building in town, the SunTrust Bank at the corner of High and Park streets, is already protected as a "contributing structure" to the Court Square historic district.

"Why wouldn't it be?" asks Huja of the Jack Rinehart-designed bank. "It's attractive, and it fits in nicely."

Indeed, the City's protection ordinance's definition of "contributing structures" is expansive: those whose "location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, or association adds to the district's sense of time and place and historical development."

That appears to mean that the newest downtown buildings– the ultra-modern metal-clad Live Arts building and Oliver Kuttner's acclaimed Terraces apartment/retail tower– are now protected.

When the developers of those structures submitted their plans to the Board of Architectural Review for permission to build, they knew they were opening themselves up to endless scrutiny. But what's to stop the City from surprising an unwary owner by deciding that a brand new structure in another part of town should be added to the list of scattered landmarks?

Not much, it seems.

Adrian Pols, is a self-described "liberal" who runs the Foreign Auto Center in a brown and yellow corrugated metal building built in 1983. He takes a dim view of the idea of preserving Charlottesville's late 20th century buildings.

"It almost sounds like something people would joke about as a parody of historic preservation," he says. "Maybe," he jokes, "they should preserve pre-fabricated steel warehouse buildings like my place."

Pols says that because he spent two years in Europe in his youth, "I've always seen historic preservation through the lens of places that really had something to preserve."

Ah, but even some European nations are clamoring to protect new architecture. In 1996, Peter Zumthor unveiled a thermal spa in Vals, Switzerland. His streamlined design featured concrete, glass, and a local vein of quartzite. The critics gushed, and Swiss authorities promptly listed the structure as a protected landmark.

"That's very unusual," says UVA's Wilson. "Buildings might want to have a little more test of them time than that."

As long as there are independent criteria, Huja says, he wouldn't object to padding Charlottesville's protected list with newer structures.

"Good buildings should be preserved," he says. "It doesn't have to be 50 or 100 years old to be quality stuff. I'll probably get in trouble with architects for saying this, but there haven't been that many great modern buildings in our city."

Huja names Dulles Airport and the Gateway Arch in St. Louis as a couple of his 20th century favorites. Each was designed by Eero Saarinen, whose winged TWA Terminal at New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport touched off a firestorm of controversy last July when JetBlue announced plans to surround the noted structure with a new terminal.

After three months of fiery debate and continuous pressure from New York's preservation-minded Municipal Art Society, the discount airline agreed to a compromise that would adapt the structure and continue its use as a terminal.

Political power

Christine Madrid French wishes she had that kind of power. Although Dwight Eisenhower's daughter, Susan, is one of the bigwigs who support her effort to save the Gettysburg Cyclorama, the Park Service remains unmoved.

French notes that the Park Service demolished the original visitors center at Mt. Rushmore 10 years ago, before she began her quest to document recent treasures.

Having earned her master's in architectural history from UVA in 1998, French is completing a book on Mission 66 which is due from Balcony Press next year.

She vows to continue documenting the recent past– and trying to save Neutra's beloved Gettysburg Cyclorama.

"We're just tenacious," says French. "I think it'll be saved. If I lost faith, it would be hard to press on."

If this were peacetime, French would consider appealing to George W. Bush. "But the President is busy," she notes, "with other issues than preserving an obscure modernist building."

Even so, as roadblocks to preservation, wars typically pale beside property rights.

But Ben Ford, president of Preservation Piedmont, says French's "windshield survey" won't inevitably lead to more legal protection. "I don't think property rights advocates," he says, "would be against the designation of structures."

However, in Charlottesville, designation has an uncanny tendency to beget regulation.

City planner Mary Joy Scala says that Charlottesville's initial list of 97 scattered-but-protected structures sprang from the City's first historic survey in 1976. And she thinks current surveys of two local districts– Rugby Road/14th Street and Oakhurst/Gildersleeve/Valley Road– could lead to creation of the City's next two design control districts. In those– as in the six existing districts– all demolitions and exterior changes including paint colors require approval from the Board of Architectural Review.

Rules wouldn't arrive overnight, Scala says.

"It's considered a rezoning," she says. "People would get plenty of notice."

City planners already take an expansive view of what deserves protection. Last summer, the Planning Department announced that it was considering dramatically expanding the City's list of historic districts with six more architectural surveys in targeted neighborhoods. Besides the two currently under study, the City soon plans to examine North Belmont, Martha Jefferson, Tenth and Page, and Fry's Spring. The Department may then pitch the idea of legally enforced building rules to those neighborhoods.

For French, the idea of surveys makes sense, as people won't save something if they don't appreciate it.

"I try to contact real estate agents," says French. "People should be informed what they're buying before they get into it. By then," she says, "a developer has a plan in place. Reacting late is expensive. Education would solve a lot of that by getting ahead of the curve."

The Lofts at McIntire

Downtown Mall

Some people may not realize that Charlottesville's Downtown Mall is actually a ground-breaking work of civic architecture. Opened in 1976, it was designed by San Francisco-based planner Lawrence Halprin, who revolutionized downtowns in 1964 with his mixed-use design for Ghirardelli Square in the city by the Bay. Closer to home, Halprin's legacy in Richmond will suffer when the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts moves forward with its plan to demolish Halprin's fountain/sculpture garden as part of a $100 million gallery expansion.

Christine Madrid French

Although an L.A. native, she finds plenty of interesting modernism in Charlottesville.

White House Motel

Mixing modern and colonial architecture was lauded when this Pantops Mountain roadside lodging was built mid-century. "Architects who did this," says French, "were seen as doing innovative work."

The Aloha

Built on Pantops Mountain in 1955-56, this modern twist on Jeffersoniana comes from the architect of the Thomas Jefferson Unitarian Church on Rugby Road: Stanislaw Makielski. "He was seriously trying to modernize Jefferson," French notes.

The Budget Inn

Martin Luther King Jr. stayed here in March, 1963. The civil rights leader was shot five years later at a similar motel in Memphis. "I think the color scheme was originally a lot like the Lorraine– with that blue turquoise," says French. However, this motel has added shutters, plants, fake lintels with fake keystones, and adopted a mauve/maroon scheme to disguise its original mid-century roadside architecture.

UVA's Treehouse Dining Hall

"That looks like a Parks Service cafeteria," exclaims French. "That's a neat little thing."

O-Hill Dining Hall

Although designed in the 1980s by renowned New York architect Robert A.M. Stern, this addition to UVA's large dining hall is doomed by an ambitious expansion.

U-Hall

"I love it," exclaims French. "It demonstrates the problems with university-owned architecture. If a building stops functioning the way it was intended, they demolish it. It's too late to put up a preservation effort, so let's get great photos of it."

Station Restaurant

"One of the best examples of re-use and preservation of a roadside structure," says French of the former Jones Wrecker space on West Main Street, adapted by architect Marthe Rowen. "The owners have successfully transformed this old gas station into a money-making, attractive establishment without disguising or disfiguring the original building. They should get an award."

The Import Car Store

French believes the original red brick of this former bank at the corner of Emmet and Hydraulic disguises the fact that this was a cutting edge-modern building when it was completed in 1963.

Terrace Triple

The theater closed about five years ago, but the bronze tile still gleams. "This is a lot like a theater I'm trying to save in Berkeley," says French, "but the Berkeley place has been a porn theater, and nobody wants to save a porn theater."

Holiday Inn

Long known as the Days Inn (until a late 1990s switcheroo), this building illustrates the "secondary phase" of development on Route 29, French says. The porte-cochere is an addition.

The Barracks Road Bank of America

"It does look like a visitors center," says French, a visitors center expert. "It has the same scale– the same emphasis on the ramps."

Wachovia at Barracks Road

"This is one of the best modern buildings in our town," French declares of this 1965 bank that recalls the roof of the Rotunda. "It even has the little oculus at the top," she points out. "It should be protected; I worry about small buildings like this one."

914 & 918 Emmet Street

"This is one of the most under-appreciated types of architecture," says French of this pair of 1960s office buildings. "Particularly with the fan-like portico and those thin vertical ribbon windows."

McDonald's at Barracks Road

"They don't build them like that anymore," says French of this 1970s fast-foodery. "You don't see that anymore– the little french-fry roof."

ALL PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

#