River bluff: How to save a park-- sort of

Less than a week after Charlottesville City Council voted to quash the developer's plans, victorious members of the Locust Grove Neighborhood Association met for a champagne celebration. They had defeated the dreaded "Tatum land swap" that would have taken three wooded acres of City parkland for a dozen houses.

That was 1999. Five years later, Stan Tatum has constructed his tenth duplex unit next to the site. One mile away, the 15 acres he would have given the City to expand Riverview Park have been green-lighted for development.

This is victory?

Orange omens

The Greenbelt is a mile-long pathway along the banks of the Rivanna River. It is home to birds, deer, turtles– and, now, orange surveyor's tape.

The orange bands popped up a few weeks ago and caught plenty of Greenbelt walkers by surprise.

"It's crazy," says Chesapeake Street resident Karl Kimbler. "It's peaceful here," says Judi Clugston. "They should keep it that way."

This is the land that Stan Tatum wanted to give to the City in 1999 in exchange for a much smaller parcel at the end of Locust Avenue. It looks like a park, it feels like a park, and it's adjacent to one of the most popular parks in the city. But these 15 acres of floodplain are not a park, and won't become a park anytime soon.

Instead, they area about to become "River Bluff," a new development of 22 upscale houses created by a three-man development team called PS2 Properties LLC.

Wilson Cropp II sold the land to PS2 in November. He had been willing to sell it to Tatum five years ago.

"It was a grand slam for the City," says Cropp, taking a break from watching an American Legion baseball doubleheader. "But you had one little neighborhood group that got up in arms, and had a lot of energy and time, and they killed it for the rest of the City."

Although Riverview Park was given to the City in 1974, its name became a household word 20 years later when it became the launch pad for the instantly popular Greenbelt Trail along the Rivanna River.

How beloved is the Greenbelt? In 1995, Dave Matthews Band manager Coran Capshaw tried to build a 7,000-person indoor-outdoor amphitheater on land behind the Pantops Shopping Center. Even though the "Pavilion at Riverbend" would have been in Albemarle County and separated from the trail by the Rivanna River, Woolen Mills neighbors turned out in such numbers that County supervisors voted unanimously to deny the Pavilion.

Cropp says he never minded that Greenbelt trekkers thought his 15-acre parcel off Riverside Avenue was part of Riverview Park. And he didn't mind when they traipsed through his business, the adjacent Riverview Cemetery. But he did mind some of the comments about the property he heard from foes of the land swap.

"They depicted it as wasteland," says Cropp. "I went to the next homeowners' meeting, and I said, 'You're stepping on a lot of toes when you talk about Riverview Cemetery that way.' "

Cropp says he bought the land and the cemetery business from Sam Jessup, a man he calls Charlottesville's "greatest entrepreneur." In 1974, Jessup donated the 26.6 acres that became Riverview Park.

For Cropp, the Tatum deal– which would have pushed the Park past the 40-acre mark– made instant sense. "The City gets rid of three acres and gets 15 acres," says Cropp. "And it's something that everybody already uses." By contrast, he says, the Locust parcel "will never get used– it's just over there growing pine trees."

How "South Pen" came to be

In 1973, Eugene German was hired as the City's parks director and asked to develop 267 recently acquired acres as "Pen Park," named for the farm which had once belonged to a 19th-century Virginia governor, Thomas Walker Gilmer. That was the northern tract; the southern tract had belonged to a family named Cox. Both tracts were dairy farms when they were acquired, German says.

Armed with $1.7 million in government grants, German, now retired, sculpted the former pastures with tennis courts, soccer fields, and the first phase of what would become known as the Meadowcreek Golf Course.

According to contemporary stories in the Daily Progress, the money didn't stretch as far as German had hoped; it wasn't enough to provide access to the little "South Pen," an eight-acre, pie-shaped piece of land just south of Meadow Creek near Locust Avenue.

Tatum's pie?

Stan Tatum got to know South Pen while developing the Locust Meadows townhouse subdivision with Frank Buck in the early 1990s. After plans for a third phase of Locust Meadows were called off, Tatum acquired some leftover parcels. He built a house on one, a duplex on another, and sold a third as a building site.

Then he came up with his fateful plan to tap into the woods next door. Coveting three acres of his City's assets, Tatum wanted to construct 12 single-family houses– with enough land left over to provide something park lovers had been eagerly seeking– a way to get to the remaining five acres of that isolated South Pen "pie."

A hemmed-in park

Pen Park is usually called a "gem" in City literature. But the bulk of it has the dubious distinction of being utterly unreachable by any means other than by burning hydrocarbons along the hilly curves of Rio Road. In plain English: by driving into Albemarle County.

South Pen is even harder to access, separated from the rest of the Park by Meadow Creek on the north and from City residents on its southern flanks by private property– i.e., residential back yards.

Even though the tip of South Pen reaches within 100 yards of busy Locust Avenue, by 1999, public access was virtually nonexistent. Some neighborhood kids built a teepee in the deep woods, but for the most part it was a forest without a front door.

When the neighbors began screaming about Tatum's plan to destroy parkland, the landlocked nature of South Pen would lead to counter-charges that neighbors were hoarding a city park as if they owned it.

One of the only efforts to unlock it for the benefit of all citizens came in the mid-1990s when volunteers cleared a portion of the Rivanna Trail along the Creek. Not to be confused with the bigger, wider Greenbelt, the Rivanna Trail can be narrow, rocky, muddy, and– as avid Hook readers know– blocked by a neighbor with a fondness for razor wire.

Win-win?

Longtime Charlottesville planner Satyendra Huja thought the land swap was a good idea. In 1998, he became City's director of strategic planning. With Charlottesville providing a majority of the region's subsidized housing, and only 38 percent of City houses occupied by their owners, the City government turned to Huja to increase the supply of middle-class homes.

Richard Brewer remembers. He was living in the nearby Locust Meadows subdivision when he heard Tatum's plans for a dozen houses in the $250,000 range.

"I think it would have been a nice neighborhood," says Brewer, "and we would have bought a house there."

After the land swap was quashed, Brewer and his family– eventually three-children-strong– outgrew their townhouse and moved away. Says Brewer, "I think the City made a big mistake."

For many other neighbors, however, there were high principles at stake.

Rallying the troops

Five years ago this week, City Council was about to consider the land swap. But neighbors had not been notified.

At the time, City Councilor David Toscano conceded that the rush to put the matter on the Council docket had been a "mistake." It led to bad feelings– and to revival of the moribund Locust Grove Neighborhood Association.

John Potter, who lives on a cul-de-sac called Bland Circle, swung into action to rally a group of concerned neighbors who began voicing their opposition to the proposal.

The idea that parkland could be sold off horrified some. Others simply didn't like the idea of 12 new houses in their neighborhood.

As newly elected neighborhood association president, Potter wrote a letter to the Daily Progress summing up the group's concerns: "It would diminish the neighborhood."

The vote– pushed back twice

Because the parkland had been acquired with government funds, says former Parks director German, selling it required a super-majority of City Council votes: at least four of the five councilors had to press "yes." So in the weeks leading up to the vote, neighbors knew that they needed to swing only two City Councilors to their side.

"The councilors need to get the message," Potter wrote in a mass email, "that this vote will be closely watched and will figure prominently in the next election. This deal would set a dangerous precedent for our park system, and it would further encroach on the beauty of the [Rivanna] Trail system," Potter said.

The vote was delayed to November, and the next election was in May.

At the public hearing, most speakers inveighed against the proposal.

Near the end of the parade of speakers, one woman stepped forward to describe how her children enjoyed playing in a teepee on that parkland– and broke into tears.

Meredith Richards, who had earlier voiced some support of the swap, changed her vote to no. David Toscano and Maurice Cox joined her. The proposal didn't just fail to win a super-majority; it was defeated 3-2, with only Blake Caravati and Virginia Daugherty voting in its favor.

"I was not really impressed with my neighbors," says Locust resident Neil Gropen. "Some kids build a teepee in the woods– and that qualified as sacred land?"

Gropen says he made a visit to the 15 acres the City would have gained for Riverview Park and came away convinced that the so-called "scrubland" by the River would make an excellent waterfront arboretum. Moreover, the full parking lot convinced him that the public loves Riverview Park.

The public does. And now so do developers.

In addition to the 22 houses of "River Bluff" slated for the Park's northern end, the southern end could soon see a development overlooking the Park's grassy front entrance.

Riverside Drive

Like the Trump Tower in New York, the houses on Riverside Drive in the Woolen Mills neighborhood overlook a highly regarded park. But that's where the similarity ends.

Besides some owner-occupied townhouses, Riverside Drive is home to low-cost and federally assisted rental properties. Many residents receive federal aid.

Social worker Rob Hull is a Riverside Drive resident who considers the impending developments on his street a breach of faith to the neighbors. Standing in his compact front yard, he looks up the street at the kids playing in the street and wonders about their safety.

"You all want to push the black people and working class out of my 'hood," he chided City Council. Hull believes that upscale housing has no place along this struggling avenue.

"Where are the poor going to live if we develop their neighborhoods?" asks Hull, an avowed foe of gentrification.

But to developer Richard Price, this diversity is something to be prized. River Bluff's 22 structures will range from $200,000 "carriage houses" to custom homes fetching as much as $500,000.

Along a pipe easement, Price's team has agreed to build a pathway down the hill to connect the existing Riverside neighborhood to the Greenbelt.

And while Price concedes that some houses could be visible to Greenbelt users, his plans clearly limit the building sites to the high rock bluff.

"In the winter, you will likely be able to see a couple of houses from the trail," says Price, "but we're trying to minimize the visual impact."

Price says the team takes its role as land stewards so seriously that they'll cull invasive tree species such as Mimosa and Ailanthus from the floodplain and replace them over time with native plantings. "It's not going to be sculpted and beautified," says Price."

And as to fears that the Greenbelt could run into a Shirley Presley-style razor-wire blockage, Price says the developers decided to expand the public Greenbelt right-of-way to 100 feet wide– about six-and-a-half acres dedicated to public use.

That's the north end of Riverside. At the southern end, Price is working with husband-and-wife environmental architects Chris Hays and Allison Ewing as Rivanna Collaborative LLC to develop up to 10 houses in the flood plain.

The spouses, who work at internationally renowned William McDonough + Partners, are already well-known in the neighborhood for the large orange house they completed on Chesapeake Street using sustainable concepts in 1999. Ewing is also the neighborhood association president.

To sustainable architects, building houses on stilts in the 100-year floodplain is the green way to develop because it preserves fragile topography. To neighbor Hull, houses on stilts within sight of a sewage pumping station illustrate something else: how relentless the juggernaut of Charlottesville development has become.

Back at Locust

Following rejection of his proposal, Tatum acquired additional land at the end of Locust Avenue– about two acres in all– and over the next three years, he built a total five duplexes. That's ten units of rental property beside the spot where he wanted to erect twelve single-family houses. The neighborhood had earned itself a 20 percent reduction in units.

"They won the battle and lost the war," says Gail Wiley, who lives nearby. "We could have had some nice houses; what we got was more rental units. Don't get me wrong– those are beautiful places to rent, but they're still rentals. The City needs more middle-income housing."

Wiley remembers that at the key City Council meeting, some of her neighbors vowed to make a pathway available– through their own yards if necessary– to help citizens reach South Pen Park. But those promises were apparently forgotten as soon as the battle was won.

"These people protected their backyards really well," says Wiley, "but the land is still just sitting there."

Not exactly. One Locust-area landowner did step forward to build a public access point over his property: Stan Tatum.

He has allowed the Rivanna Trails Foundation to erect a sign at the driveway to his duplexes directing citizens over his property and onto the parkland he coveted in 1999. Such a gesture became instantly more important in 2002 when Bland Circle resident Shirley Presley unrolled her trail-blocking concertina wire. Tatum's land now provides the Trail's official detour around that obstruction.

Has Tatum received any thanks from the neighbors? Not yet– but wait.

"I guess he should have," says John Potter in an interview earlier this week. "If I haven't thanked him, let me go on the record now."

Win-win?

Today, lest anyone see this story as a cautionary tale for neighborhood action, Potter sees the fight as a success.

"I'd call it a win-win," says Potter. "Things are a lot better than they could have been. We've got a nice piece of parkland with trails running through it."

Potter was among the volunteers last month who helped construct a "rock hop" over Meadow Creek. That helps hikers truly connect the orphaned South Pen piece to Pen Park proper.

The orange tapes by the Greenbelt, as we heard above, have caused plenty of outrage. "But the real outrage," says Woolen Mills resident Kevin Cox, "is the net loss of 12 acres of potential parkland."

For others, however, the alleged loss is tempered by the fact that Tatum was in fact offering 15.5 acres of floodplain. And Wilson Cropp admits that the high land was not included in the swap acreage, and thus the bluff probably would have been eventually developed anyway.

As for Tatum, "It was a learning experience," he says. "I had this naive feeling that Council would look at this and say, 'What are the attributes of the project?' What happens is the people who come out for meetings are the people who don't want something. You've just got to get political to get things done."

Riverside Park and one of those orange omens.

Riverside Park and one of those orange omens.

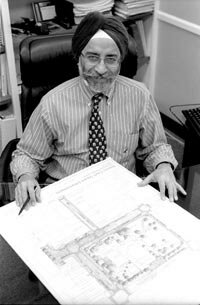

Stan Tatum: "The City wanted housing. I thought it was a deal made in heaven."

Charlottesville's longtime planner Satyendra Huja won a $100,000 federal grant and oversaw the 1993-94 creation of a mile-long trail through Riverview Park northward to Free Bridge.

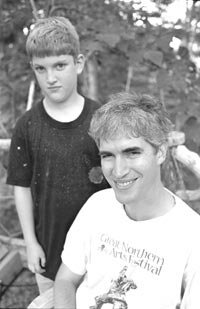

Bland Circle resident and former Locust Grove neighborhood association president John Potter.

Heather Peck: "All of this belongs to God, and it's on loan to people."

Riverside Drive resident Rob Hull has been fighting the two developments slated for each end of his street.

Environmental architect Chris Hays wants to put up to 10 houses on stilts in the floodplain.

Jodi Clugston: "Once they start putting up houses here, they're going to put houses up everywhere."

Ayasu Watts and Rashan Clarke ride on Riverside.

You too can enjoy Riverview Park.

PHOTOS BY JEN FARIELLO

#