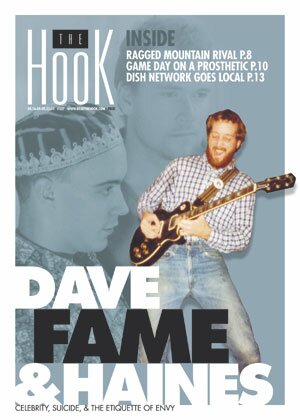

Dave, fame, and Haines: Celebrity, suicide, and the etiquette of envy

Dave Matthews took a careful sip of his coffee. He'd just been to the dentist, and the right side of his face was noticeably swollen.

"The guy's standing there prying open my mouth, scrapping the crap off my teeth and making my gums bleed and telling me about what a fan his daughter is– and could I sign a t-shirt for him after my cavity was filled," Matthews said.

He took another sip of coffee, and it dribbled down his chin. Behind us, the barista girls working the counter at Greenberry's were trying to act like it wasn't such a big deal to have a rock star in the room.

"Is it bad?" Matthews said, almost sheepishly. "Do I look stupid?"

"You can hardly notice it," I lied.

Matthews smiled and cocked his eyebrow, a familiar gesture that had become iconic to millions of fans. "You know, I was thinking about Haines the other day. It's funny you asked me to talk about him."

Everyone has a Haines story, a story about how he turned his light on them. I wondered what Dave's was.

"He was definitely an influence for a while." Matthews took another careful sip of his coffee. "You know," said Matthews, adopting an uncharacteristically serious tone, "I think about suicide a lot."

It was early 2001, and we had met to talk about Haines Fullerton, a local musician, bartender, and muse who had killed himself five years earlier, so the comment wasn't completely out of the blue. Still, it wasn't what I had expected to hear from a man about to make the cover of Rolling Stone for the first time. Or was it?

In 1994, just days after Kurt Cobain shot himself, writer John Updike was asked to comment on the suicide and describe the spiritual crises of rock stars.

"I think all of mankind operates in the shadow of spiritual crisis," Updike said. "Rock stars– they're simply middle-class kids whose dreams have come true too soon, and maybe because they're very reckless and self-infatuated, they're trying to become angels. That was certainly the feeling you had in the late '60s and early '70s, when so many of the real stars just went down like rockets: Joplin, Hendrix, and others."

"You think about suicide?" I asked.

Matthews nodded solemnly.

"Of course, I'd never really do it because of how it would affect other people," Matthews said, abruptly changing gears, "particularly those I love. I couldn't do that to them."

Matthews' sudden shift seemed to come on the heels of my puzzled look, as if he were suddenly afraid of being a downer, or had revealed too much too fast, or been caught trying to affect a brooding darkness he really didn't have, or was simply trying to upstage Haines. It was hard to tell where he was coming from.

"This may sound harsh, considering we're talking about Haines," Matthews went on, "but I see it as a selfish thing to do. The thing is, Haines was unselfish to the point of wanting to kind of erase himself.

"I remember jamming with him, and he'd come up with some chord progression or fragment of a song I liked, and he'd say, 'Here, take it, use it, it's yours.' And I was like, 'No, it's yours, I'm not going to take it.' Later on, when he set up an early recording session for the band in Memphis, we could hardly tell he was there in the studio because he was scurrying around, checking sound levels, staying out of the way like he was trying to be invisible."

I was interested in Fullerton's own flirtation with rock stardom and the demise of his band, The Deal, which flourished in the mid-'80s.

Nearly a quarter century after the band's founding, Deal fans still talk in nostalgic terms about the undiscovered treasure of the music and their affection for Haines, as if they were a phenomenon that poignantly marked a certain time, a phenomenon that the broader culture had failed to discover and embrace.

Certainly, the story of The Deal has all the elements of a classic rock tragedy, a kind of perfect dark parallel to the success of the DMB. In addition, the two rock narratives are intertwined.

Both Haines and Deal front-man Mark Roebuck had songwriting credits on DMB albums, Roebuck for "The Song that Jane Likes" and Haines for "#34." Roebuck and Matthews had also recorded a tape together in 1989, and it was Roebuck who first convinced Matthews to perform at an open mic night at the old Eastern Standard.

The Deal was formed in 1979 in Charlottesville by Mark Roebuck, Eric Schwartz, Haines Fullerton, Hugh Patton, and Jim Jones. By 1981, the band had earned a full-page spread in Andy Warhol's Interview magazine, in which they were described as a new group dedicated to "high harmonies and low morals, the East Coast answer to the Beach Boys sound."

Having developed a loyal following, they were doing live gigs to packed houses up and down the East Coast, and soon found themselves dubbed one of the "20 Best Unsigned Bands" in the world by Musician magazine.

Eventually, the band attracted the attention of music legend Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan's ex-manager and founder of Bearsville Records, who signed them to a five-record recording contract. But Grossman's Bearsville and its parent company, Warner Brothers, had a falling out that resulted in an intense legal battle.

Undeterred, Grossman flew to Europe to find investors to save his label. However, midway through the flight, Grossman suffered a fatal heart attack. Haines and Roebuck made a few more attempts to revive The Deal, but by the end of 1987 it was clear to both of them that it was not going to happen.

It took Roebuck nearly ten years to recover from the band's failure; he finally decided to pursue a degree in social work. However, according to Roebuck, Haines never completely got over it.

It was a struggle Roebuck knew something about. He had remarked a number of times that Matthews' success was sometimes painful to him, that the green-eyed monster of envy loomed large if he thought about it too much.

Roebuck was one of the last people to see Haines before he shot himself. He and Haines had not spoken in years, and Haines wanted to patch things up. By then, Haines had a nearly cult-like following of locals who had been influenced by his spiritual theories of channeling and physical transformation, a situation that had been worrying Roebuck.

As far as Roebuck could tell, the philosophy had a lot to do with Haines' interest in A Course in Miracles, a kind of intellectual's self-help guide, or "thought system," for understanding the teachings of Christ. In fact, not long before Haines' death, he told Roebuck that God was speaking and working through him to bring remarkable changes into the world.

On September 20, 1996, Haines bought a handgun at the By-Pass Market, a hunting and fishing store that used to stand at the site of the new CVS by Free Bridge. A security guard found his body later that night in the pool house at Ivy Gardens apartments. He was 37.

During an outdoor memorial service, Roebuck performed live for the first time since The Deal broke up, his voice and hands shaking with emotion. In the audience were the two women who had borne Haines' children within the past three months.

***

The first time I saw Haines was the first time I saw the DMB play at Trax in 1993. I'd just arrived in Charlottesville and had an apartment within walking distance of the now-demolished club where the band played regular Tuesday night gigs.

One of my first impressions during that show was how happy everyone was, as if the angst of grunge, the vaudeville of '80s pop, the anger of punk, the poetry of '70s folk, and the tired example of the Grateful Dead had finally been cast off.

At the center of all this bliss was a tall, boyish looking man with a high forehead, short curly blond hair, large sad eyes, and a sweet, angelic grin who wore a tennis shirt, khaki shorts, and white Keds. He stood at the edge of the dance floor moving slightly to the music, looking immensely pleased with what he was hearing and what was going on around him. He looked so openly joyous and confidently unreserved that I remember it bothered me.

No one could really be like that, I thought. Every so often, someone would go over to say hello to him, usually a woman, and after a few words, they would hug for an unusually long time, the kind of hug people gave each other in airports and train stations. And then Haines would close his eyes, smile, and raise his head toward the stage lights.

In hindsight, it's easy to see that whatever it was about the DMB that people responded to was almost certainly first felt by Haines.

"You know," Matthews said, "during our tour last summer somebody got hold of an old video from one of our shows at Miller's. We stuck it in, and for about five minutes it was just a shot of that empty little stage. Then all of a sudden Haines walks across the screen. We all looked at each other and shuddered.

"He was a powerful personality. He had a knack for believable flattery, and at the time I just sucked it up. He also used to tell me how important it was that the band communicate, that we develop a strong way to communicate with each other early on because when we were real big, communication would be harder.

"At the time, sitting there playing our little weekly gigs at Eastern, I was like, 'Yeah, sure Haines, when we're real big.' But he was right. I remember one time right before one of our Tuesday night gigs, Carter was pissed about something and tried to walk out before the show started, said he was going to quit, said he was sick of being the drummer for this stupid ass band. I stopped him at the door and wouldn't let him leave. We confronted each other, we talked, and we worked it out..."

During a lull in our conversation, Matthews and I walked over to CVS to get a pack of cigarettes. On the way back, a barber was standing nervously beside a bench with a pile of posters. As we passed, he stepped forward.

I'd taken my son to have his hair cut by this man several times over the years, but at that moment I might as well have been a lamp post. He had a pile of DMB posters he wanted The Dave to sign, and in his delirium at being in his idol's presence, he was speaking way too fast, too scripted, and clearly embarrassed by this ambush. But he pressed forward, the goal of signed posters for friends and family outweighing any concern for dignity– and leaving him blind to the fact that he had met me at least a half dozen times.

Matthews politely inscribed each poster to the names the guy requested, and when he was finished the guy quickly retreated into the barber shop with his prize. From inside, all eyes looked out at Mathews like a crowd gathered around a street performer juggling bowling pins and blowing fire out his mouth.

"Is it always like this?" I asked.

"No, it gets much worse."

***

When Matthews and I began talking again, I thought about how easy it is to be charmed into abandoning yourself as you gaze upon celebrity, even if it's only a face on a magazine at the supermarket, and how it seems to operate all around us like a smiling, well-dressed demon seeking to highlight our inadequacies by gossiping about the glamorous lives of others.

Indeed, over the decades we've been exposed to the media machinery of our celebrity culture, we've been conditioned to "know" these people we've never met, to invite them into our lives, to carry on an inner dialogue with them.

"To a greater or lesser degree," Richard Schickel writes in Intimate Strangers: The Culture of Celebrity, "we have internalized them, unconsciously made them part of our consciousness."

The problem is that this kind of false intimacy creates unrealistic expectations and makes disappointment and self-loathing inevitable. Schickel writes, "Another part of the approaching stranger's mind is, of course, aware that he is totally unknown to the celebrity. And he resents that unyielding fact. A chip grows on his shoulder. An undercurrent of anger."

The larger danger to society, Schickel warns, is that our obsession with celebrity has elevated the power of personality over the power of ideas, ideologies, and even authentic human connections.

"We have come a very long way," he says, "in a very short time to our present isolation, subjectivity, and desperate hope that the cult of personality may substitute for a sense of organization, purpose, and stability in our society."

For even the most intelligent among us, the connection to celebrities we like or chance to know (even to the ones we hate) is somewhat more charged by this phenomenon than we like to admit. Perhaps we manage it better than the barber did, but it's still there. Like Roebuck, I have also felt a powerful awe and envy for Matthews' life and success, which at times has been like a quiet and powerful assault on my spirit, and has even found its way into my dreams.

***

Later that night, Roebuck and I met Matthews for drinks at Court Square. When we arrived, Matthews was still doing his interview with the Rolling Stone writer, so Roebuck and I waited at the bar.

"You know, there was a time when Haines had such a strong influence on me that my ego and my belief in myself totally depended on him," Roebuck said. "He poured himself into me just like he poured himself into Dave.

"It was like he had a spiritual virus that needed a host to survive. It was like he martyred himself to people, like he sacrificed himself," he went on, "and yet there was some mean-spirited, angry, egotistical aspect to it. He was a hard person to hate, but I hated him for years."

Roebuck smiled when asked about the last time he saw Haines. "He wanted to see me so he could apologize for all that stuff. And he did. Of course, it was said by a man who believed himself to be the son of God at the time, or something like it. Haines always took things to extremes. You know, he was such a perfectionist, such a purist, that it's no wonder he felt like he had to be Christ when he found him. It was a big part of why the band failed, I think. Even if Grossman had lived, I think we would have burned out. Haines was just too much of a perfectionist to be a success." Mark laughed. "And all I really thought about was getting laid."

Was Haines crazy?

"He was bi-polar, for sure. If he were a patient of mine now, that's how I would diagnose him," Roebuck said.

Mark turned and looked over at Matthews and the reporter.

"I'm just thinking about how maybe he was always bi-polar, always crazy, and that all those years I struggled with him, all those years I depended on him, all those years I believed in what he said about me and the future of the band... that all those years I was just dealing with someone who was mentally ill."

***

When the Rolling Stone interview ended, Matthews waved us over, and for the next few hours we riffed wildly on writing and books, the music business, famous people Dave had run into (Jim Carrey, Chelsea Clinton, Mick Jagger, Dylan, Nelson Mandela), women, Tiger Woods, bowel movements, drugs, sex, and a dozen other taboo subjects. We smoked a zillion cigarettes, consumed vast quantities of Knob Creek whiskey and Bass Ale and laughed until our sides ached and our eyes watered. The Rolling Stone writer excused himself early, sensing what was coming, I think.

Later we headed down to the C&O, grabbed the corner table, and settled in. Whenever I looked up from our conversation or returned from the bathroom, I noticed there were more people there and that all the tables and chairs in the room and all the people in them had either turned in our direction or moved slightly closer– as if all objects feel the gravitational pull of planet Dave.

What had started out as a spirited and scatological conversation at Court Square Tavern had– in the small, smoky, dimly lit confines of the C&O– become an orgy of impulses and broken boundaries. People poured through the space surrounding our table, leaning over us to listen to Matthews or shake his hand, the women putting out everything they had, as if maintaining any mystery or dignity might consign them to the heap of the unnoticed. (One woman actually sat on my lap for almost an hour, and when I met her again at a party a week later, she didn't remember me.)

The whole room seemed to be pulsating wildly with energy, as if everyone were auditioning for a spot in Matthews' memory.

At one point, I had to go out to the parking lot and breathe steadily so I wouldn't throw up. When I returned, it was over.

The lights were up and the music down, and people were filing out the side door. Two impossibly thin girls sitting on Matthews's knees were now playfully insulting him, telling him how fat he was getting and that he was losing his hair, to which a loaded and tired Mathews just stared down at the table submissively and signed the credit card slip for our massive bar tab.

"But we still think you're soooo cute," one of the girls said, sending them both into a fit of laughter, their hands and mouths and thin legs all over Matthews like giant insects on a corpse.

***

Later on, we sat in Dave's car in the Wachovia parking lot and listened to a demo of the DMB's upcoming album, Everyday. I sat in the back beside a mountain of mail addressed to the king while Roebuck sat up front. It was 3:30am.

Roebuck and Matthews talked music, just as they had when they were both bartenders on the Downtown Mall. In a perfect world, I imagined, Haines and Mark and Dave and everyone who'd ever dreamed of playing music for a living would all be rock stars.

However, in this world, the songs we were listening to would be on radio stations everywhere in a few months, the videos would come out, the summer tour would get under way, and Matthews would get his picture on the cover of Rolling Stone. And more money and fame would pour down on him like rain.

It was the excess that seemed to mark Haines and Matthews, I began to think, that willingness to go to extremes. Haines just went ahead and believed he was holy, threw himself headlong into his music and into people's lives, and then went ahead and bought that gun and headed off into oblivion.

Matthews just went ahead and stepped into the ferocious arena of American popular culture and the terrible responsibility of fame. They both had taken bold, self-infatuated leaps: Matthews into the mind of the public, Haines into the hands of God.

One of Haines' favorite hangouts, the pool at Ivy Gardens

PHOTO COURTESY MARK ROEBUCK

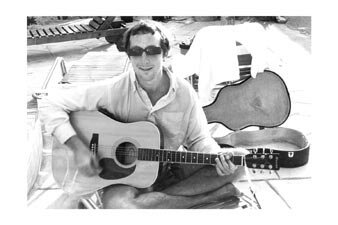

Dave Matthews and Mark Roebuck, who collaborated on some songs in 1989. PHOTO BY TALMAGE COOLEY

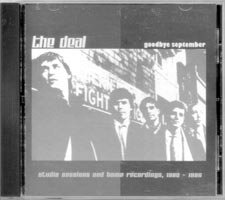

In 2003, an independent power pop label called Not Lame Records, famous for rediscovering The Posies, releases some songs from The Deal as Goodbye September.

NOT LAME RECORDS

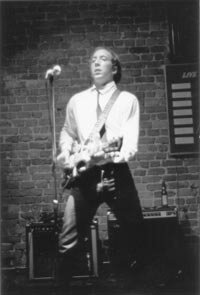

Haines (center) in an undated band publicity shot

PHOTO COURTESEY MARK ROEBUCK

Haines Fullerton played lead guitar for The Deal.

PHOTO COURTESY MARK ROEBUCK

Was Fullerton surrounded by followers, friends, or enablers?

PHOTO COURTESY MARK ROEBUCK

In Interview: Counter-clockwise from upper left: Mark Roebuck, Jim Jones, Eric Schwartz, Haines Fullerton, and Hugh Patton.

INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

#