The verdict: Sisk's family speaks out

In the same court on the same day that a cocaine dealer was sentenced to nine years in jail, a former UVA student who stabbed a local firefighter to death received a sentence of just three years– less than a third of the allowable maximum for a voluntary manslaughter conviction.

Almost no one is satisfied.

Certainly not the parents and friends of 22-year-old Walker Sisk, who died after he was repeatedly stabbed by then-UVA third year Andrew Alston. Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney Jon Zug had sought a second-degree murder verdict, which carries prison time of up to 40 years. Friends of Sisk, who died on 14th Street from one of 20 knife wounds, call the sentence an outrage.

Alston's family, from Lower Gwynedd, Pennsylvania, isn't happy either. They were hoping to see him released from the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail, where he's already spent a year.

And bearing the weight of deciding a case in which one young man is dead and another's life in ruins is the jury, which had to deal out justice under the eyes of the anguished families– and the community.

Appalled friends

"It's sickening," says Carrie Keyser. She graduated from Western Albemarle High School in 1999 with Walker Sisk, whom she describes as "a good ole country boy."

"Everybody I've talked to is shocked," says Keyser, who couldn't bear to attend the trial. "I think it's sad you can buy your way out of punishment," she says.

At the trial, the defense team led by renowned Alexandria lawyer John Zwerling introduced the jury to a bespectacled Andrew Alston who occasionally burst into tears. The defense also produced a parade of expert witnesses– including a martial arts coach and a crime scene analyst– who claimed it was possible that Sisk had stabbed himself.

"I was blown away after I sat there and watched the defense," says Dustin Medley, a friend of Sisk's who attended three days of the trial. "I can't believe how liberal Charlottesville is," he adds. "You get more time for three DUIs."

Calling Andrew Alston's testimony "Oscar award-winning," Medley says he was incredulous when Alston paused to apologize to the jury before detailing the profanity in the exchange between Walker Sisk and Alston's friend Bill Fegley.

"If that's not well coached," says Medley, "I don't know what is."

He adds, "It just goes to show, if you have money, you don't have to pay the consequences."

Past haunts

Gail Lowe took six days off work to attend the trial. She'd known Walker Sisk since he was in grade school with her daughter, Lauren, who also attended the trial.

When the jury returned its guilty verdict on November 9, a year and a day after the killing, says Lowe, "I was happy he'd been found guilty, whether second degree or voluntary manslaughter."

But when the jury returned a day later with a three-year sentence– after asking the judge whether Alston would get credit against his sentence for time served– Lowe's red-rimmed eyes gave away her dismay. "I'm not happy with the verdict," she says. "He took a life. He's going to hurt someone again."

Lowe believes Alston's past was discounted. During the sentencing phase of the trial, the jury learned about events of Halloween 1998 in Pennsylvania. Alston, then 17, was part of a pack of teens who chased and attacked younger boys, one of whom was kicked badly enough to require reconstructive surgery.

Alston, although not "the kicker," pleaded guilty to a charge of "criminal conspiracy to commit aggravated assault" and served six months in a juvenile detention facility.

What the Charlottesville jury didn't hear about was Alston's alleged act of local violence. Last year, two months before Sisk's death, Alston's then girlfriend, another UVA student, filed charges alleging he had struck her in the face.

In a statement hurriedly written by Alston's father, a lawyer, who arrived in Charlottesville hours after the alleged attack, Karen Graham recanted her story, and Judge Robert Downer, citing reasonable doubt, acquitted Alston.

"Mr. Alston's dad was already trying to put the squeeze on her," said Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney Ron Huber at the assault trial. "He knows exactly what to do. You get to the witnesses as soon as possible."

How significant was that November 21, 2003, acquittal in Alston's sentence for killing Walker Sisk?

In Virginia, a manslaughter conviction carries a maximum sentence of 10 years, and studies show that prior violent offenders can expect to serve nearly seven years in prison. However, for first-time violent felons, which Alston was, by virtue of escaping the assault charge against his former girlfriend, the median voluntary manslaughter term is just 4.1 years.

[See sidebar for more on Virginia's punishments.–editor]

It's impossible to say how much Robert Alston's early intervention in the assault and battery case contributed to the not-guilty verdict, but had Andrew been a repeat offender at the time of the Sisk killing, median sentencing figures suggest he would have been looking at two or three more years in prison.

A similar burst of paternal involvement emerged after Sisk's death. According to the prosecution, Robert Alston checked into the Cavalier Inn at 8am on November 8, 2003, about six and a half hours after the stabbing. As Charlottesville is approximately a four-hour drive from Pennsylvania, the timeline suggests that Robert Alston was already on the road before his son's 3:52am arrest.

"His father's paid his way out of everything," says firefighter and Sisk friend Jimmy Schwab, who was with Sisk the night he died. "If [Alston] had had a public defender, he would have done 40 years."

Parents' anguish and "voodoo judo"

Every day Howard and Barbara Sisk sat at the murder trial of the killer of their only son. They knew it would be tough to get a second-degree murder verdict, but with two eyewitnesses, Howard Sisk thought Alston would certainly get more than a "slap on the wrist," as he describes the sentence.

"If they thought he was guilty, where's the punishment?" asks Sisk. "If they thought it was self-defense, why didn't they acquit him?"

Sisk believes the jury was swayed by the suggestion that as a UVA student Alston would be capable of rehabilitation– and by the parade of expert defense witnesses, one of whom earned over $20,000 for his testimony.

While the jury was out for over three hours deciding the sentence, Sisk expressed his contempt for what he calls the "voodoo judo" defense.

Alston, who had taken an eight-week aikido course in 2002, testified that when he saw Sisk– whom he described as a "furious man" saying, "I'm going to kill you, faggot"– he was so terrified that he pulled out his pocketknife, which, he claimed, Sisk promptly took and lunged at him.

An aikido expert demonstrated to the court how Alston could have grabbed Walker Sisk's hand and made him stab himself 20 times.

"It was hard to sit there and listen to," says Howard Sisk. "If Walker was a raging beast, why did 450 people show up at his memorial service?"

What's fair?

Two years ago, a Charlottesville judge raised a community outcry by sentencing two local parents to eight years in prison for serving alcohol to minors. The case touched off wide debate about appropriate sentencing.

In Virginia, voluntary manslaughter is the least serious of four intentional killing offenses, preceded by capital, first-degree, and second-degree murder.

Voluntary manslaughter is distinguished by two factors:

* the killing must have occurred in the "heat of passion," and

* the passion had to have been caused by "adequate" provocation.

The 'Lectric Law Library says that in order to be "adequate," the provocation must be such "as might naturally cause a reasonable person in the passion of the moment to lose self-control and act on impulse and without reflection."

That would explain the defense effort to portray Sisk as an angry tattooed drunk (his post-mortem blood alcohol level registered .19 - .21) attacking the diminutive Kenny Alston, Andrew's brother, who was among those in the 14th Street altercation that night.

Prosecution witnesses contended that Kenny Alston was so drunk (six and a half hours after the incident he blew .15) that he tumbled into Sisk during their verbal exchange.

Left for the jury to surmise were Andrew Alston's thoughts. If they believed he acted with "malice," they could convict him of second-degree murder.

Was this a chance to test a knife he'd been recently showing off, or was he really fearful for his and his brother's lives?

A late 1990s federal study found that about 82 percent of voluntary manslaughter deaths result from fights. But if what happened between Walker Sisk and Andrew Alston was a fight, say Sisk's friends, it wasn't a fair fight.

Closing ranks

"People feel kicked in the stomach," says Chief Doug Smythers, who heads the Seminole Trail Fire Department where Sisk volunteered.

Volunteer firefighters in Albemarle County work full-time jobs and then put in 100 hours every month. In addition to that, during the week of the Alston trial, they made sure at least two or three uniformed firefighters sat in court– usually there were more– in memory of their slain comrade.

"All the people in the fire department have taken on the responsibility of protecting the public," Smythers says. "They feel the public let them down."

To Smythers, there was no question of malice– a criterion for a second-degree murder conviction– in the 20 wounds, including a three-inch gash that penetrated Sisk's heart.

"How many nights do thousands of people go to the Corner drinking alcohol and nobody gets stabbed?" asks Smythers. "How many times do people get in fights and no one dies?"

Smythers has called in crisis intervention experts to deal with his disheartened firefighters. "I'm concerned I'm going to lose members because people say, 'Why should I volunteer my time when this is how the public treats us?'"

Alston's emotions

This murder trial is not the first tragedy the affluent Alston family has suffered. Every day, Andrew's parents– Robert, a town supervisor in Lower Gwynedd, and Karen, a school counselor– sat in court along with his sister and aunt. For that family, the day of sentencing was the most emotional.

Joined by cousins as well as second-son Kenny Alston, who the prosecution believes disposed of the knife, they listened as friends, religious advisors, and a psychotherapist described a family still reeling from the suicide of their oldest son, Timothy, two years ago. He, too, was a volunteer firefighter.

"To this day, Tim's room has never been cleaned out," said clinical psychologist Marilyn Minrath, who testified at the sentencing. Minrath, who'd met with Andrew 26 times, called him "a lost soul" upon his return to UVA after Tim's death. She also said he was remorseful and tormented by the death of Walker Sisk.

The Alston family's wounds don't move Howard Sisk. "His brother chose to kill himself," he says. "Walker didn't choose to kill himself. Andrew Alston did choose."

When the jury returned to the courthouse to deliver its sentence, Alston's parents, brother, and sister leaned together on the bench as if in a moment of prayer.

Robert Alston declined to speak to reporters after the sentence was announced, saying only, "I don't think it's appropriate to comment."

"They're devastated," says defense lawyer John Zwerling, who describes a family that can't conceive that their son and brother is a convicted killer. "They want him home," he says.

Zwerling has won other controversial cases. Some revolve around a knife, such as Lorena Bobbitt's infamous 1993 severance and disposal of her husband's penis. Some revolve around a gun, such as the case of Countess Valentina Djelebova Artsrunik, charged as an accomplice in the 1997 murder of a Charlottesville jewelry dealer.

Zwerling, too, was disappointed by Alston's sentence.

"On the one hand, I was relieved because it easily could have been more time," he says. "On the other hand, I'm not happy. Andrew shouldn't have to do more time. The good thing is the end is in sight."

Zwerling hopes that Alston can serve the rest of his time in the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail. "At least he has a support system there. He's not too far from his family, and he has Dr. Minrath and his priest to provide some support mechanisms."

One place that won't necessarily welcome Alston back is UVA. According to spokesperson Carol Wood, former students hoping to return must reapply. "And clearly their record would be carefully looked at," says Wood.

Even if Alston could get past the admissions committee, he might be facing charges from UVA's own Judiciary Committee that would preclude his return.

Zwerling and co-counsel Andrea Moseley, who have offices in Alexandria, are aware that some local people consider them out-of-town hired guns.

"We were playing an away game, whereas Mr. Sisk's family has very deep roots that are very widespread in the community," says Zwerling. "And when he was alive and sober, apparently he was a very well-liked person. That wasn't the person my client knew."

Zwerling notes, "His father was a real gentleman even to me throughout the proceedings."

Now that the jury has set the maximum sentence, Sisk's family and friends, who had to sit quietly and listen during the trial, get their turn at the victim impact hearing before final sentencing in February.

That's why Zwerling believes it's better this case was tried rather than plea-bargained.

"Andrew needed to tell his story," says Zwerling. "Walker's friends need to tell their story. If the Sisks need to unburden, it's part of the healing process."

Unsolved mystery: the knife

One of the trial's unsolved mysteries is what happened to the knife Alston wielded on the night of November 8, 2003. In his closing argument, Zwerling said Jimmy Schwab, a fellow firefighter who was with Sisk that night, or another of Sisk's friends, may have disposed of the knife.

"Jimmy Schwab could have picked up the knife– what?" scoffs a disbelieving Dustin Medley. "Everyone is pretty outraged by that."

The prosecution had another theory about the knife: Kenny Alston disposed of it.

After the 1:30am stabbing, Alston's friends fled the scene, and trial testimony indicated that Kenny Alston burst into the 14th Street apartment where his compatriots– including Andrew Alston– had immediately assembled. A police officer, who followed a blood trail to the apartment, testified that Kenny Alston was carrying his brother's blood-smeared car keys.

The defense countered that Kenny was far too drunk to avoid police and dispose of the weapon.

"Ultimately, they weren't there," says Schwab of the defense attorneys. "I was. I didn't go anywhere, and police picked me up and took me to the police station."

A jury of one's peers

Four women and eight men spent five hours deciding to convict Alston of voluntary manslaughter, and more than three hours to decide on a three-year sentence. The jury was composed of several teachers, one a UVA professor. It included a laborer, a stock clerk, a financial advisor, a pharmacy technician, and a student.

"It was a difficult decision, but one we felt best for the community," says jury foreman Juandiego Wade, an Albemarle County planner.

According to Wade, the jury spent the most time discussing the definition of malice. "I looked at all the evidence," says Wade, "and didn't think it was malice– just tragic on both sides."

Did Alston's testimony sway the jury? Wade says no, explaining, "By that time, we'd already heard so much information."

And did the jury buy the claim that the stabbing was self-defense? "Some people thought there was self-defense," Wade says.

During the course of "a very emotional debate," Wade says, the jury reviewed all the evidence.

The jury agreed on voluntary manslaughter, but when it came time for sentencing, "Everyone had an idea what they wanted, and it ranged from one to 10 years," says Wade. "Everyone had to give and take a little."

Juror Liz Kutchai calls the whole experience "one of the hardest things I've ever done. It was a heavy burden of responsibility." She adds, "I feel profoundly, profoundly sad, and I will have a heavy heart for a very long time."

Juror Gail Houser, although declining comment on specific aspects of the trial, also mentions the strain of deciding Andrew Alston's fate. "There were so many emotions," she says. "I took this seriously. It was a very difficult thing to do."

Even Howard Sisk, as he waited to hear the sentence, conceded that the jury had a tough job. "I wouldn't want to be in their shoes," he said.

Afterward, however, he felt the jury overlooked one important fact: "What they fail to understand is their son is alive, and our son is dead."

During and after the trial, both prosecution and defense attorneys complimented the jury on its diligence and refrained from criticizing its decisions.

Prosecutor Zug warned the Sisk family that a voluntary manslaughter conviction was a distinct possibility. "Numerous times, Walker could have walked away," he reminded them.

Still, he admits disappointment with the verdict: "I stand firm with this as a murder case. I had the horses to pull that load."

But in the firestorm of criticism following the sentence, there are milder responses.

"That's what the jury thought was appropriate," says Albemarle Sheriff Ed Robb. "Our system is great, but it's not flawless. If we agree our jury system is the best and fairest in the world, then there are times that we don't agree with it."

Attorney Steve Rosenfield says, "People who form opinions about whether a sentence is too harsh or too light rarely have sat in for all the evidence the jury has heard. It's pretty unfair to be guessing whether the judgment was right or wrong.

"The parents of the defendant and the parents of the decedent," Rosenfield adds, "will never be satisfied."

Is Alston's three-year sentence for voluntary manslaughter a "slap on the wrist"?

According to the Virginia Sentencing Commission in its 2003 annual report, convicted criminals without a prior violent record serve a median of 4.1 years for voluntary manslaughter, while those with severe violent records average 8.6 years.

But those statistics are of little consolation to people who loved Walker Sisk.

The trial "definitely didn't offer me any closure," says Jimmy Schwab. "This is harder to stomach than last November."

"I'm never going to get over it," says Howard Sisk. "Closure– that's just a word shrinks use."

PROSECUTION

"What's the price of life in Virginia?" Jon Zug, assistant commonwealth's attorney, asked the jury in his closing. "The Sisks don't want vengeance– they want justice."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

DEFENSE

John Zwerling has led such high-profile cases as his successful exonerations of Lorena "temporary insanity" Bobbitt, Valentina Djelebova, and the "Virginia Paintball Terrorists."

PHOTO COURTESY JOHN ZWERLING

Wearing a suit, wire-rimmed glasses, and occasionally bursting into tears, former UVA biology student Andrew Alston dodged a 40-year sentence for second-degree murder and could be out of jail within two years.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM BARRATT/THE CAVALIER DAILY

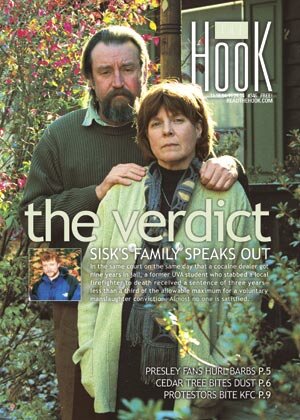

Last November, Howard and Barbara Sisk lost their only son, Walker. This November, they lost their faith in finding justice for their son's death after a jury handed his killer a three-year sentence.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"Obviously they didn't think our son's life was worth that much," says Howard Sisk, after the man who killed his son got a three-year sentence.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Outdoor lover Walker Sisk planned to return to Alaska, where he spent the summer of 2003.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SISK FAMILY

Seminole Trail Fire Department Chief Doug Smythers says Sisk's fellow firefighters feel "kicked in the stomach" by Alston's sentence.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#