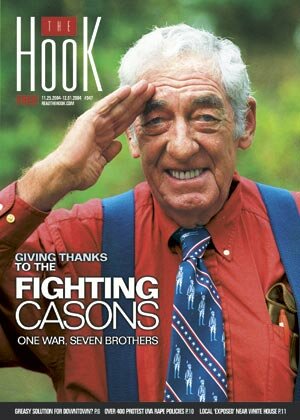

Seven society: The Fighting Cason brothers and WWII

World War II veterans are said to be dying at the rate of 1,000 a day. But there's one local family that sent seven sons into the armed forces– and not only did all seven survive the conflict, but six of them are still alive today to tell their tales.

Of the seven Cason brothers who served during World War II or the ensuing occupation, all but one served in the Pacific theater, and five were in some of the most horrific conflicts in Okinawa and Iwo Jima, and in the bombardments of Japan.

Hanging on the wall in Jack Cason's Albemarle County home is a framed portion of a banner with six stars that used to hang on his parents' front door. It honored six of Mr. and Mrs. L.E. Cason's sons who served in the armed forces. A seventh joined later.

None of the brothers was wounded, but the youngest, the one serving in the occupation force after the war, sustained the most serious injury– at the hands of a United States sergeant.

These are their stories.

Leonard Ezra Cason Jr.

Before the war started, Ezra got his draft notice, so he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He trained as an armament specialist, serving for 47 months from 1941 to 1945.

In early 1942, Ezra was shipped to New Guinea, where his squadron received new P-38 planes. "The pilots loved that plane because it could outmaneuver the Japanese," he says. "Before the war was over, our squadron shot down over 400 Japanese planes, which was a record for the Pacific. Charles Lindbergh, even though he was a civilian, came to New Guinea and flew several missions with the squadron.

"Sometimes there were crashes, and the pilots had to parachute into the jungle. We named our unit 'The Headhunters' because there were headhunters in New Guinea, but they were friendly to us, and they would find a way to get our pilots back to us."

On December 5, 1944, the squadron landed on Mindanao in the Philippines from where they bombed French Indochina and other Japanese-held islands. Ezra was now a master sergeant.

"The Japanese dropped incendiary bombs. They exploded at treetops and set fire to everything. I had a foxhole outside my tent, and I jumped into it. The bombing scared us to death because we didn't know what was happening. "

The following May, Ezra was in the hospital having his appendix removed when his name was drawn to be discharged. "I left the hospital and went back to my squadron. But they had already been shipped out, and I was all alone. Finally, my captain got me on a boat. But my friends were gone, and I never saw them again."

Ezra was discharged on June 30, 1945. For recreation, he learned English country dancing, which led to a job at the Blue Ridge School in Dyke where he taught dancing, then became a house manager and ran the school's farm. It was here that he met his wife, the former Isabel Stiles, who was a student at the school. They were married in the school chapel and have four children, five grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren. In 1981, he retired from the University of Virginia's housing division and for 18 years taught night classes in basketry at Albemarle High School. Isabel is a clerk in the urology department at the UVA medical center.

Charles Cason

When Charles was 23, he was drafted into the Army– September 19, 1943– and assigned to the Military Police of the First Calvary Division. On June 6, 1944 he was shipped to Brisbane, Australia. "That was the day we invaded France," Charles says. "I felt kind of scared."

After being transferred to New Guinea, to wile away the three months before he was re-assigned, he picked a coconut, engraved his mother's address in Charlottesville, and mailed it to her. Sixty years later, the coconut– its engraved address still distinct– is prominently displayed on a bookshelf in his Charlottesville home.

Assigned to the mop-up division coming in behind the front lines, Charles began to see the effects of war in Leyte in the Philippines. "We went to a small town, Tacloban, the capital, which had just been cleared of the Japanese. The Philippines and their people were still all tore up. We landed in monsoon season, and there was nothing but mud everywhere. I remember seeing a truckload of bodies coming from the mountains where there was still fighting. I saw their legs hanging out.

"Then I was set up at the front gate of a field hospital looking at IDs. It was here they were bringing in the dead and the wounded, some bleeding from the head. That was the worst thing I saw during the war.

"My strongest memory is my landing in Leyte. There were seven bodies on the shore. One was an American Indian who had been mistaken for a Japanese. But that was also when I shook hands with General MacArthur. He came ashore the next day and walked up and down the beach. He was my hero. He said, 'I will return,' and I returned with him.

"On August 8, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, just as we were getting ready to invade Japan. Now there was no invasion necessary, but we did go to Japan. We got into Tokyo Bay on September 21, and were located just two ships away from where General MacArthur was signing the peace treaty with the Emperor.

"After that, we went on shore and took over a lot of weapons from the Japanese civilians. I still have a Japanese sword and a Japanese rifle."

As an MP, Charles was among those ordered to arrest Tojo, but the Japanese general had already committed suicide.

Charles was discharged on February 6, 1946. He and his wife, Frances, have three children, three grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. After doing lawn maintenance 23 years, he retired at the age of 70.

Ralph Cason

Ralph was drafted into the Navy in February 1943. By August, he was on the U.S.S. Chester, a heavy cruiser with nine 8-inch guns, eight 5-inch guns, anti-aircraft artillery and many other weapons. His duties included helping with refueling at sea, manning the guns at battle stations, and doing "whatever else they needed."

On November 19, Ralph was in his first battle at Tarawa, one of the Gilbert Islands. He describes torpedo bombers, air combat, bombardments, and land invasions.

"I was carrying the ammunition in this battle. In later battles, I was pulling the trigger. It was sort of nerve-wracking, being my first battle. This battle is the one I remember the most because it was in my line of sight."

The Chester sailed to Eniwetok, Saipan, Ulithi, and Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. Later, it was based in Adak in the Aleutian Islands from where it was to head for Japan.

"We tried three times before we made it. We would start out under fog, but then the fog would lift, and we'd be spotted by a Japanese plane, and we would turn back. The third time, we were under cover of fog, and I could hear the planes overhead. It made me shaky. We bombarded the island off the north coast of Japan. The fog stayed with us until we got away from there.

On February 15 and 16 ("just before my birthday,") says Ralph, the Chester was part of the invasion of Iwo Jima, one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific.

"It was a terrible experience," Ralph remembers. "We lost more men than any other place we had ever been.

"On the day of the invasion, a rock opened up and a big gun came out. It hit other cruisers, but we never drew fire. At night, the wounded and the dead would be brought out by barges, and the barges would lose their way and not be able to find the hospital ship. They would be calling for directions.

"The next day, I saw this ship about seven stories high coming at us, and I ran to the other side and grabbed a steel post. I was sure it would hit us broadside, but our ship turned, and the troop ship struck the tail end and knocked off a propeller. We had to go back to California to be repaired."

From Adak, in September 1945, after the peace treaty was signed, the Chester went back to a northern Japanese naval base. "We went in with triggers on our guns, and along the channel we saw gun after gun after gun, all with white flags. We stayed at the base for a couple of months to remove all the ammunition, load the barges, and take them out to sea and dump it.

"We were given permission to go ashore with $5 worth of yen– it was about more than I could carry. I went shopping, but I got awful hungry because it wasn't safe to eat anything. In one store, I saw an apple, and I wanted it so bad, but I couldn't eat it.

"There were brand new '42 and '43 model Fords and Plymouths. In the cars' trunks were charcoal burners that made gas. With the way gas is now, it may be a good way to go."

Ralph stayed in Philadelphia for a year putting three ships– including the U.S.S. Chester– in mothballs. He was discharged in November 1947.

His post-war employers included a dry cleaning establishment and an insurance company. Finally he became manager of the Fry's Spring Beach Club, where he stayed for 21 years until his retirement in 1979. He has one daughter and two granddaughters.

William "Bill" Cason

When Bill turned 17, he first tried to join the Merchant Marine. But he was turned down because he wasn't strong enough.

"I wanted to go in because all my friends had gone in the service, and I wanted to join the crowd and get on with it. Wasn't anything to do around here. Finally, they accepted me the second time, about three months later."

Bill was in two branches of the armed forces. From January 1945 until June 1946 it was the Merchant Marine; from June 1946 until June 1949, he served in the Army Air Corps, as the Air Force was then called.

After being trained as a fireman and engine room water tender, he sailed for Venezuela on a tanker escorted by Navy ships to pick up oil. "This trip was dangerous because the war was still on, and the Germans were there," Bill says. "I was still just 17, and I was really scared."

After a two-week leave, he sailed to Marseilles on a troop ship. "We brought back about a thousand GIs who had been wounded," he says. "This trip was memorable because the Navy was dropping depth charges to dislodge German submarines. One surfaced to surrender, and we brought the crew of six onboard. I can see those boys right now; they were so happy to be aboard our ship. They'd shine our shoes two or three times a day, and we didn't have to clean our rooms at all because they did."

As a Merchant Marine, Bill was required to make a trip every 30 days. "Every time we came back, we got a good reception," he recalls. "There would be bands and girls. It was a sight to see."

After returning from a trip to Antwerp, he did not return to his ship. "I stayed home over 30 days– and Uncle Sam sent me a greeting card saying 'You are now in the Army,'" he says. "I didn't want that, so I enlisted in the Air Corps."

Bill trained for sea-air rescue, but when he was ordered to Okinawa, he refused. "I jumped ship twice. They put me in the brig. One day they said to me, 'You don't want to go to Okinawa; we'll send you to the coldest place in the United States.' That place was Great Falls, Montana," he recalls.

"I was on the flight line. For every plane that came in, we had to stand by in case something happened. General Eisenhower came in, and I stood by with our fire equipment for his plane. I didn't meet him personally, but I did salute him when he came down.

"Lots of troops and planes were going to Greenland and Iceland, getting ready for Korea," he says. "One time a plane crashed. It was 40 degrees below zero, and we'd turn on the water hoses and the water would freeze all the way to the ground. It sure was the coldest place in the U.S."

Bill was discharged on June 6, 1949. He worked first at Sperry Marine and then was a corrections officer at the local jail. He has three children, four grandchildren, and two great grandchildren.

Jackson "Jack" Cason Sr.

During the war, Jack contributed to the war effort by making landing barges for the invasion of Japan at the Horace E. Dodge Boat and Plane Corp. in Newport News. After the war ended, he joined the Navy. Jack was 17 in 1948.

"They were probably going to draft me into the Army when I was 18, and I didn't want the Army, so I enlisted in the Navy," he says.

Trained as a radioman, he was sent to Astoria, Oregon, near Fort Clatsop, site of the 1805-06 winter encampment of the Lewis and Clark expedition. ("By the way," says Jack, "William Clark's father owned the farm across the road from us in Albemarle County. George Rogers Clark, his brother, was born there.")

Although he was in the Navy, Jack was never on a ship. "They were all in mothballs," he says. "We had the 19th fleet in mothballs, 444 ships. Everything you could think of in small craft were right in front of our office building."

Trained as a radioman, he was sent to Adak in the Aleutians where Ralph's ship, the Chester, had been based. "It was a little island about two miles wide and seven miles long," he recalls. "I stayed there 18 months until my discharge.

"Not much happened in Adak. When they sent me up there, they said there would be a woman behind every tree. But there were no trees. It was so windy. It blew gale force winds all the time. Rainy, cloudy, dismal weather. But it had good salmon fishing."

Jack compensated for the lack of entertainment in Adak: He was a teletypist in the search and rescue office, the sports reporter for the base newspaper, and he formed a softball team called "The Pencil Pushers."

His most memorable experience was going to meet his brother, George, waiting in California to ship out to Okinawa. "I took an eight-day leave, and we hit all the sights: San Francisco, the Bay Bridge, Oakland," he remembers. "But I spent all my money, so I didn't have any for bus fare to get back. I got a free flight back on a C-47, and one of its engines quit. I couldn't see any house or towns, just ice and snow.

"I had never flown before, and I had to put on a parachute. A major who helped me put it on warned me not to pull the cord too soon or I'd hit the tail. I never needed it though, thank goodness. That C-47 was the safest plane ever made. It flew all day on one engine. "

Jack was discharged in 1950 and sold cars, insurance, real estate– even groceries at Hilltop Market. He and his wife Barbara have two children and four grandchildren. He still works in his garden growing vegetables and selling them at the City Market.

George Cason

George Cason tried three times to join the Air Corps before they finally accepted him. "Five of my brothers were serving during the war, and I wanted badly to serve, too. I tried to join when I was 13, but they sent me back home. I tried again at 14, and they sent me home. Finally, I devised a scheme.

"I got a driver's license that said I was born in 1928. I was really 15, but with the driver's license making me three years older, I was accepted." That was August 7, 1947.

"I wanted to join so badly because all my brothers had served. I wanted to prove that I was a man, too."

There's an irony to George's enlistment. While his brothers were in some of the fiercest battle zones of World War II, all of them came home without suffering any wounds. George, however, serving after the war, was severely injured twice due to his fellow servicemen.

Soon after his arrival in Okinawa, George was in a truck accident, which put him in the hospital for 40 days with a separated shoulder. He had been in the back of the truck, which hit a pothole and tossed him over a 30-foot cliff.

"We'd have to go 20 or 30 miles for a haircut, but after the wreck I refused to go," George says. "Finally, the captain said I had to go. He put me in another truck, and it hadn't gone two miles when the driver wrecked that. When we got back to the base, I told the captain I wouldn't get a haircut unless he drove me. And he did."

George can make light of that incident, but he still gets angry when he remembers another.

"When four of us went to the village for a stage show, two MPs arrested us for being in the village which they said was off-limits. They kept us in jail for four or five days. Three of the guys were radio operators who knew Morse code, and they were talking to one another in code. The MP told us to cut it out, but they continued," he says.

"I didn't know Morse code, but the MP came back, jerked me out of bed and told me to stop it. I said I couldn't stop what I hadn't done. One MP held a gun on me while the other pulled a billy club and started beating me. They beat my arms black and blue. I just about passed out.

"When my commanding officer came for us, he wanted to know what had happened to me. They put me in the hospital, busted that MP to a private, and put him in the brig. That was a terrible experience for a sergeant to do something like that."

George spent 17 months on Okinawa. Then he was transferred to Omaha, Nebraska. "While I was there, rules changed, and they taxed servicemen. That meant I was making less than I had been making, so they offered me a discharge. I took it. Lucky I did, because they discharged me on May 8, 1950, and on about June 25, the Korean War started. I had just been discharged and had just turned 18 when I got a draft notice. I went to the induction office and I told them I just had gotten out, and I wasn't going back in."

George was a life insurance agent, automobiles salesman, railroad brakeman, and realtor. He also had his own nursery and landscape business. George and his wife Hazel have four children, 11 grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

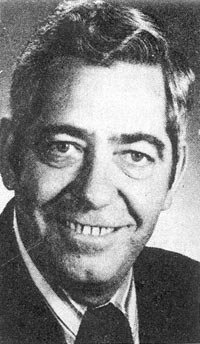

Lee Cason

Lee was an automobile insurance agent when he died in 1982 at 56. Carolyn Cason Talley still has her father's pants and pea jacket that she wore in high school. She also has a doll that Lee sent to his aunt, a photo album, a weather-beaten book, "The Blue Jackets' Manual," dated 1940, a compendium of instructions for seamen, and a small lined notebook, empty except for a list of battles.

"My father loved to hunt and to garden and to sell at the City Market," Carolyn recalls. "He never talked to me about his experiences of the war." He did talk about it with his brothers.

After Lee went into the Navy in 1943, he served in the North Atlantic and the Pacific theaters on the U.S.S. Bull, a destroyer escort converted to carry underwater demolition teams. The notebook shows that he was in the Solomon Islands, Marshall Islands, Saipan, Ulithi, Luzan, Leyte, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

"He was valued for his eyesight," Jack recalls. "He could pick out the suicide bombers before most people spotted them.

"Lee told me about the battle at Okinawa where the Japanese flew suicide planes so close that he could see the pilots' faces. "

Jack also remembers a time when Lee sneaked away from the base in Brooklyn while they were converting the ship. "It was the weekend, and he didn't think they would take roll call," he says. "But they did. The Charlottesville police came in the middle of the night, looking for Lee. My dad said he'd gone back, but they wanted to check who was there.

"Billy, George, and I were here. Dad went to the bottom of the stairs, and the first name he called was Lee. The policeman said, 'I thought he wasn't here.' Dad said, 'I can't keep these boys straight, I got too many of them.'

"Lee was put into the brig for seven days on bread and water. That was the punishment at the time. You got a meal every third day."

After Lee left the service, he attended the Jefferson School of Commerce on the G.I. Bill. While working at Western Auto on Main Street, he would take his coffee breaks at Timberlake's drug store where he met his future wife Hope McCauley.

His brother George was with Lee when he died. "We were having lunch at TJ's on the Corner, talking about the North Carolina-Virginia basketball game. All of a sudden, he looked at me and said, 'Something just hit me.' He put his head down and said, 'George, I'm gone.' He had an aneurysm at the base of his skull." He is survived by two children and three grandchildren.

Nancy Cason Roberts

The only girl in the family, Nancy did not wear a uniform, but as each brother went to war, she served in her way, providing comfort for their distressed mother and helping her father with the planting.

"I was only five years old when Ezra went into the service. I remember my mother crying when each boy left," she says. "My father was concerned about them too. They had been a big help on the farm, and when they left he was worried about feeding the rest of us. I remember my father always behind a plow. When the younger boys left, for a while I was the only one to help with the planting.

"The boys weren't allowed to tell my mother what coast they were leaving from, so they devised a code. I can't remember what the west coast code was, but if they were leaving from the east coast they would write, 'Take care of Charles' car.' She then knew about where they were.

"Every Sunday, we listened to Gabriel Heater, a radio correspondent who reported on the war. We children had to be perfectly quiet when he spoke. It was my mother's only connection with her boys except for their letters– and they had portions blacked out. But my mother learned that if she put the letter above the lamp, she could read it. After they [censors] discovered that, parts of the letter were cut out.

"Until I was 10 years old, I slept in my parents' bedroom. Then when the boys left for the service, I was able to get my own room."

Nancy acquired a military life too after marrying her high school sweetheart who served with the Air Force, including time in Viet Nam. They returned to Virginia in 1974, where she worked in radiation therapy at UVA for twenty years before retiring. The couple has two children, nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

A Cason Legacy

Every Saturday in the spring, summer and fall, residents of Charlottesville and nearby counties flock to the City Market that George Cason started in 1973.

"I ran for City Council in 1972, and an item on my platform was a city market in Charlottesville where people could buy produce and enjoy the day," says George. "I lost the election, but the market took off.

"At the first market there were five of us Cason boys– me, Jack, Lee, Bill, and Ezra– selling vegetables," he says proudly. "Now it's a sight to see. There are about 100 stands with vegetables, flowers, crafts, baked goods, and more. It's like a bright beautiful carnival."

Last year, during an anniversary celebration, the five brothers received plaques for their 30 years of contributions and participation, and George was honored as the market's founding father.

Although this year's City Market season has ended, the Cason "boys," who still have stands– George, Bill, and Jack– will no doubt be back in the spring with their bounty of eggplant, corn, beans, or tomatoes.

Citizens might remember to thank them for founding the gathering that is so much a part of Charlottesville summers– and for their service to their country so long ago.

In October 2000, Congress authorized the Library of Congress to arrange interviews of all war veterans. In Central Virginia, this Veterans History Project has been organized by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society, which asked Bea Mook to interview the six surviving Cason brothers, their sister, Nancy Roberts, 68; and Carolyn Cason Talley, Lee Cason's daughter.

A version of this story originally appeared in Silver Linings, a quarterly publication Mook edits for the Jefferson Area Board for Aging.

#

SIDEBAR- The Casons of Stony Point Road

The Casons were farmers who grew up near Stony Point Road in Albemarle County. L.E. and Mary Cason bought the farm in 1919, sold it in 1950, and moved into the city. Son George bought the farm back in 1961 and sold parcels to Jack, Bill, Lee, and Ralph. Jack and Bill built their homes near the foundation of the family home (which burned in the 1960s).

All seven Cason brothers returned from the war, and six still live in and around Charlottesville. They are Ezra, 86; Charles, 84; Ralph, 82; Bill, 76; Jack, 74; and George, 72. Lee died in 1982 at the age of 56.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CASON FAMILY

Ezra Cason

Ralph Cason

Charles Cason

Bill Cason

Jack Cason

George Cason

Lee Cason

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CASON FAMILY

Lee Cason's widow, Hope (left), and his daughter Carolyne Cason Talley peruse a family photo album.

#