Film flap: Local shutterbug 'exposed' in D.C.

Professional photographer Bill Emory went to Washington on Election Day to celebrate democracy with his camera. Two weeks later, he is still shaken from what happened to his film a block away from the White House.

"I felt totally violated," says Emory. "We were there to celebrate the whole election process." Instead, he discovered just how much the nation's capital has changed since 9/11.

Emory met up with an old prep school buddy, Ray Wittenberg, and on November 3 they strolled around Lafayette Park, the popular protest point just north of the White House.

"The National Organization of Women was having a rally, and they'd just heard that Kerry conceded," relates Emory.

Continuing on, Emory spied a sign on a security hut that caught his fancy: "100 percent ID check." Emory snapped a shot of the sign with the security booth and White House in the background, and he and Wittenberg meandered on.

"We'd gone 15 to 20 yards when this man appears, and he wants to confiscate my film," says Emory.

"I'm a patriot," protested Emory.

"The guy's a professional photographer," said Wittenberg, who was carrying recording equipment and captured the encounter on audio.

The officer was not dissuaded. "He didn't seem to understand why we'd never before seen a sign that said '100 percent ID check,'" says Wittenberg. "I said, 'I'm from Arkansas.'"

"I don't want to escalate this," the officer can be heard on the tape. "I've given you your only option."

When Emory, loath to turn over his film, asked for time to think, the officer says, "I've got to go, sir. I'm going to have to take your camera."

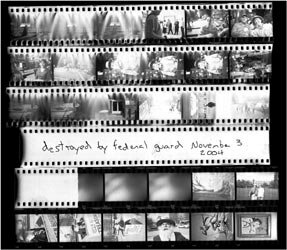

And for the first time in 35 years of taking photographs, Emory did the unthinkable: He opened the back of his camera and deliberately exposed his film.

On his website, Emory posts some light-damaged shots taken before and after the incident. And he vents his remorse at not asking for the officer's name and agency.

Trying to get that information in a city with multi-jurisdictional security like Washington isn't easy.

Secret Service spokesman Jonathan Cherry would not confirm that Secret Service staffs the perimeter checkpoint about a block away from the White House at Madison Place and H Street– or whether such a booth would bear signs like the one Emory photographed– and whether it's illegal to photograph them. "We don't discuss our protective means or methods," Cherry says.

Would the Secret Service confiscate film if such signs existed? "It's possible, based on circumstances," he says. "In general, the Secret Service does not allow photos of our security measures."

He adds, "I have to ask, are you taping this call?"

The Metropolitan Police do not confiscate film, according to Officer Kenneth Bryson in public affairs. He explains that photography of federal buildings has been tightened in the post-9/11 world, and notes, "A great number of buildings are federal in Washington."

Bryson is hesitant to comment on another agency but says what Emory photographed sounds like a Secret Service checkpoint.

And he suggests that in such a situation, "The first thing you need to get is a name and an agency."

"That is a Secret Service checkpoint," says Sergeant Scott Fear with the U.S. Park Police, which is responsible for Lafayette Park. Photography is allowed in Lafayette Park, says Fear, and in areas where cameras aren't allowed, signs are posted.

That's what infuriates Emory: he saw no sign or other indication that snapping a shot of a quirky little sign would lead to such a disconcerting encounter.

So how is a citizen to know what's allowed?

"I can make no other comment on this matter," answers the Secret Service's Cherry.

Over at the Associated Press, photographer Pablo Monsivais captured a shot of the man who set himself on fire outside the White House November 15. By email, he replies that he's never heard of anyone having his film confiscated.

His colleague at the AP photo center, Ron Lizick, concurs. He says the Secret Service doesn't like pictures being taken of agents on top of the White House. Otherwise, "I know of no restrictions at all," he says.

Fourteen checkpoints surround the U.S. Capitol, and Wittenberg is dismayed to see Washington so fortified. "They've just gone overboard on security," says Wittenberg. "People are stepping over the line in the name of Homeland Security."

The irony for Emory is that he has a long line of military forebears. His great-grandfather, Rear Admiral William H. Emory, got his Naval Academy appointment after waiting to see Abe Lincoln at the White House in 1862 and asking the President to intercede with his mother, who'd already lost two brothers at sea and didn't want her son to go.

The story seems so 19th century. Now, Emory faces the painful realization that in the seat of democracy, coming from a long line of patriots is not enough, that in the post-9/11 home of the free, all Americans are suspects.

"It troubles me that I backed down so readily," Emory writes on his website. "It troubles me that there are guardians of our freedoms who hold those same freedoms in such low esteem."

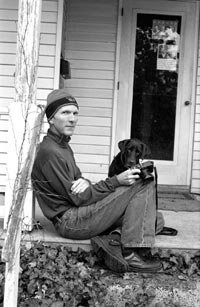

Bill Emory didn't find out the Secret Service doesn't permit photography of its White House checkpoints until he took a photo. Then he was in big trouble.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Local photographer Bill Emory posted light-streaked photos that survived an encounter with a federal agent outside the White House. An audio tape of that incident is on his website, billemory.com/NOTES/pocket%20litter.html

PHOTOS BY BILL EMORY

#